From indie hero to acid house innovator…

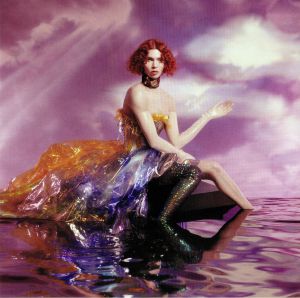

Pluto– Rising (Expanded Edition) (Love Record Stores 2021) (Glass Modern)

For any indie band, to be ‘big in Japan’ is a status symbol. But at Juno, we firmly believe being ‘big in the Balearic Islands’ should hold just as much weight, and we’re sure Rolo McGinty – former Woodentops frontman and mastermind behind the alias Pluto – can vouch for us.

Released in 1995 and reissued now by Glass Modern, ‘Rising’ was Rolo’s first solo electronic album. But before we dissect it, we’ll explain Pluto’s origin story. Like being bitten by a radioactive spider, the promise of electronic music ensnared Rolo in the early ‘90s, endowing him with a superhuman enthusiasm for emotive techno, trance and Balearic house.

The catalyst for this bionic upgrade was ‘Why? Why? Why?’ – the smash single by Rolo’s band The Woodentops – all the way from 1985. Multiple layers of irony and random chance enshroud the hit-worthiness of this song. Its first release was a mix by Adrian Sherwood, but it didn’t pick up steam until 1987, when a more uptempo live version came out. Oddly enough, that was the version that became the Balearic classic.

And to add to this, the ‘Tops weren’t originally Cafe Del Mar residents nor San Antonio strip saunterers – they were a rather sophisticated South London indie band. Their first big break wasn’t a meagre spot of DJ play by Paul Oakenfold, but rather a bigup from The Smiths’ Morrissey in the music magazine Melody Maker. “Anyone sane living in this world will realise… that The Woodentops bring with them a new age of enlightenment” – thus spake Morrissey, dousing the band in the social proof they’d need to later sign with Rough Trade.

After the co-opting of ‘Why? Why? Why’ into the Balearic scene, Rolo’s sleep schedule began to slowly de-align itself from that of his tour managers and label affiliates. He’d head into the night for a spot of clubbing, as soon as they went home and off to bed. It was this attraction that led not only towards his experimenting with analog gear, synths and sampling (hence the semi-electronic Woodentops album ‘Wooden Foot Cops On The Highway’) but also the rather under-the-radar Pluto alias, which saw him perform at Heaven in the mid-90s, flanked by two backup DJs in silver reflective space outfits.

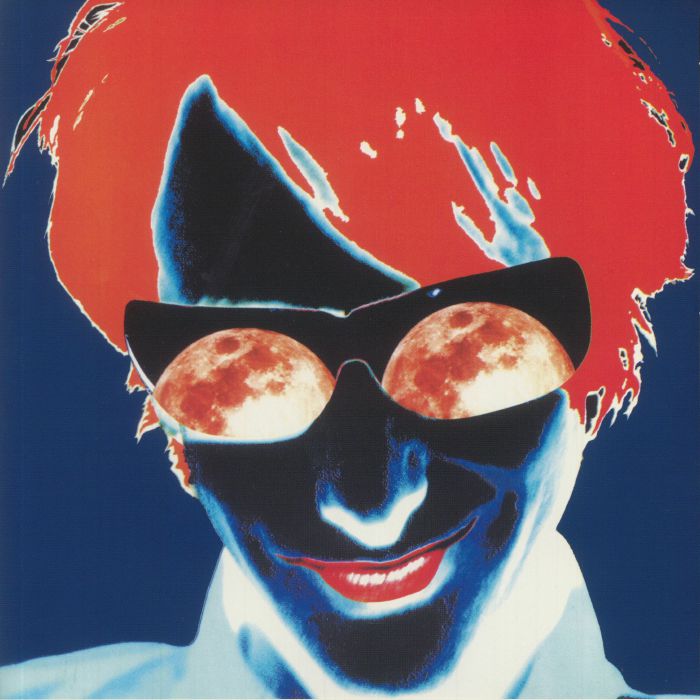

All this neatly frames the first album as Pluto, ‘Rising’. The album’s title – and the art, depicting an undiscovered musico-planetary realm, Pluto, framed like ripe prey in Rolo’s glasses – clearly matches the emotions he felt during his exodus into electronica. We all know that feeling. Getting into a new style of music does indeed feel like a swell of buzzing joy, rising out from the pit of one’s stomach.

As if fulfilling this sense of potential, every track on ‘Rising’ is a well-developed house and techno throbber, well worthy of sharing a label home (London’s fabled I.T.P. Recordings) with much bigger names like MLO and The Advent. Three deep techno cuts – ‘Free To Run’, ‘Diablo’ and ‘Rockerfeller’ – preface a slow-burning balearic beat bit, ‘Let Me Lie’. An outlier, this track is ridden by an unknown vocalist in an almost street-soulful manner reminiscent of The Chimes or The Family Stand. “Let me love you,” it repeats, while its reversing drums melt our inhibitions.

One track deserves all the praise it can get, and that’s the midway point, ‘Sumista’. Owing to Rolo’s foundations in the faster end of band music, it works in an unusual 4×4 beat at a higher tempo, seeming to draw on everything from drum n’ bass to hardcore to ska, all while blending its paints on a palette made entirely of acid-laced Mallorcan wood. It’s at double the speed of most Balearic chuggers, effortlessly carrying the digit of Rolo’s energetic live personality into the structure of a dance track.

The extent of Rolo’s production chops don’t truly make themselves known until the latter half, at which point, the dub ricochets of ‘Hardware Waving’ contrast prismatically to the acid chaos of ‘Mach 3’, seemingly predicting the styles of later dance figureheads like Primula and Morgan Geist. ‘Magic Man’ is the star of the show, being the album’s most sentimental track – but, as if acknowledging that such moments of bliss are fleeting, we soon return to unserious Balearic vibes on ‘Nimble’ and ‘Sueno Plutino’.

The final track title roughly translates to “I dream of Plutinos”, which are invisible objects that orbit Neptune in perfect motion. Such is the feeling we glean from the story behind this album, and from Rolo’s musical career. Out from the chaos of restless and janky post-punk comes the Neptunian, planetary order of electronic dance music, in all its chilled-out unisons and tessellations.

Jude Iago James