Dusted Down: The Unlikely Origins Of Bleep Techno

Matt Anniss takes a trip back to 1988 to discover the story behind Unique 3 and the Mad Musician’s “The Theme”, a record that accidentally spawned one of British dance music’s most distinctive genres.

Matt Anniss takes a trip back to 1988 to discover the story behind Unique 3 and the Mad Musician’s “The Theme”, a record that accidentally spawned one of British dance music’s most distinctive genres.

Most people mistakenly believe that bleep techno – that most British of electronic music styles spawned in the post-industrial North of England during the tail end of the Thatcher regime – started with the launch of Warp Records in 1989. According to the narrative, bleep emerged from Sheffield as a fully formed genre, with the Forgemasters – famously named after a local steel mill – providing the style’s first salvo.

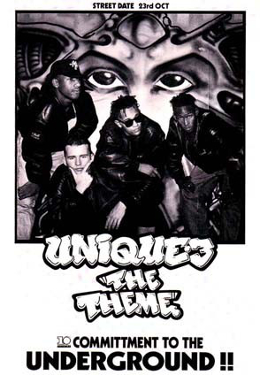

In fact, the style’s roots lie further north, in West Yorkshire. Every micro-genre has to start somewhere; in the case of bleep techno, it was the spare bedroom of a non-descript terraced house in Bradford. It was here, sometime in 1988, that members of local DJ crew Unique 3 joined forces with an old school friend to jam out tunes. Out of these sessions emerged a fusion of ideas, and subsequently a record, that would go on to transform British dance music. That record was “The Theme” – a sparse combination of alien bleeps, clanking TR-909 percussion, spooky chords and a speaker-rattling bassline. Pressed and released by its makers on the short-lived Chill Records imprint, “The Theme” quickly became an anthem across the North of England, introducing the world to what would become known as “Yorkshire bleep and bass”, or simply “bleep”.

In hindsight, the name of the single’s other track, “It’s Only The Beginning”, seems spookily prescient. Within weeks of release, the distinctive minor key refrains and pulverizing basslines of the record could be heard surging from the speakers at clubs in Bradford, Leeds, Sheffield and Manchester. Such was the impact of the 12” in Yorkshire that it inspired a generation of producers around the county to create their own similarly raw, bass-heavy and strangely futuristic tracks.

By the beginning of 1990, bleep – with its dub soundsystem rattle and bedroom take on Detroit futurism – had taken the UK by storm, with Nightmares on Wax, LFO, Forgemasters and Sweet Exorcist, amongst others, all recording massive club hits. Even now, 26 years on, bleep remains influential; Richard Sen’s recent record on [Emotional] Especial is effectively a remake of a 1990 bleep techno tune, while the likes of Paul Woolford and JD Twitch will happily talk for hours about the genre’s distinctively British charms.

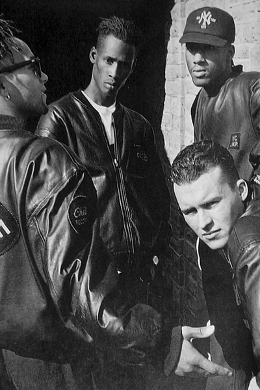

In some ways, Unique 3 were unlikely techno heroes. They started life as a B-boy DJ crew in the mid 1980s, and by 1988 were renowned across West Yorkshire for their love of hip-hop, house and 808 electro. The crew was initially made up of DJs Ian Park and Kevin ‘Boy Wonder’ Harper, plus mic man Patric McGill. The latter rapped as if he was from Brooklyn, rather than Bradford, and was regarded as something of a ladies’ man. The trio was particularly well regarded on West Yorkshire’s black music scene, which was as good a place as any to hear the latest, cutting-edge American dance music sounds. Aside from the Warehouse in Leeds, the Hacienda in Manchester and Jive Turkey in Sheffield, few mainstream clubs in the region played house music. Back then, Detroit techno – a particularly fresh influence – was regarded simply as another strain of house.

In some ways, Unique 3 were unlikely techno heroes. They started life as a B-boy DJ crew in the mid 1980s, and by 1988 were renowned across West Yorkshire for their love of hip-hop, house and 808 electro. The crew was initially made up of DJs Ian Park and Kevin ‘Boy Wonder’ Harper, plus mic man Patric McGill. The latter rapped as if he was from Brooklyn, rather than Bradford, and was regarded as something of a ladies’ man. The trio was particularly well regarded on West Yorkshire’s black music scene, which was as good a place as any to hear the latest, cutting-edge American dance music sounds. Aside from the Warehouse in Leeds, the Hacienda in Manchester and Jive Turkey in Sheffield, few mainstream clubs in the region played house music. Back then, Detroit techno – a particularly fresh influence – was regarded simply as another strain of house.

Unique 3’s Ian Park and Patric McGill were particularly interested in house music. They used to go on regular shopping trips to Manchester on Saturday afternoons, where they’d pick up the latest imports. It was an old school friend, would-be musician David Bahar, who drove them over the Pennines. “They were among the best DJs in the North of England at the time,” Bahar says. “You could only hear that kind of music in black clubs, or if you were friends with the best DJs. Myself, my then pregnant wife, Ian and Patric would go over to Manchester to get the latest tracks. This way I got to hear the newest house records before 90 per cent of other musicians in the North.” By the middle of 1988, Unique 3 had become two, with Harper leaving to join forces with George ‘EASE’ Evelyn under the Nightmares on Wax pseudonym. They would later become similarly successful with their own brand of “bleep and bass”.

With Harper out of the picture, a mutual friend, Delroy Brown, suggested to Bahar, Park and McGill that they tried making music together. “At the time all I had was a keyboard with a sampler function,” Bahar recalls. “Ian and Patric had a TR-909, but no sampler. I had a sampler, but no 909. Getting together made sense. So, one day we sat down in the spare room of Ian’s mum’s house and did this track called “Jazz Freak”. Ian programmed the drums, I was on the keyboard and Patrick added some string parts. We all thought it was the best thing we’d done and arranged to meet up again.”

The trio began recording together regularly, with each would-be producer bringing additional equipment to the sessions. “Delroy Brown had this brother called Derrick who owned a kick-ass soundsystem,” Bahar remembers. “He was one of the biggest DJs locally on the black scene and had some good bits of kit, like reverbs and that. We managed to borrow some stuff off him as we went along. Ian was working really hard on the drum programming and we really felt we were getting somewhere.”

During the sessions, Bahar stumbled upon a sound that would later become one of the stylistic hallmarks of bleep techno. “I was a massive raw bass fan, and I wanted the wildest, dirtiest bass sound I could find,” Bahar says. “At one of the sessions I heard low register feedback come through the speakers that shook the house to its foundations. So, I got a tape deck and plugged a mic into the mixer to record the feedback. I kept hold of that, and when we recorded “The Theme” and the other track on that 12”, “Only The Beginning”, we used it for the bass tone.”

Having failed to secure a record deal on the strength of their demos, the trio chipped together and booked some time in a local studio owned by the brother-in-law of another mutual friend. “When we got in the studio for the first time I was in music heaven,” Bahar enthuses. “While Ian was talking to the engineer I got on the Yamaha DX7 they had in there and started playing the bassline for ‘The Theme’. When I filled in the spaces with my right hand, Ian turned around and said ‘that’s good’. As he was a kick-ass DJ, I just thought ‘keep playing it’. It had this weird bleep sound, which is how the famous melody came about.”

Having failed to secure a record deal on the strength of their demos, the trio chipped together and booked some time in a local studio owned by the brother-in-law of another mutual friend. “When we got in the studio for the first time I was in music heaven,” Bahar enthuses. “While Ian was talking to the engineer I got on the Yamaha DX7 they had in there and started playing the bassline for ‘The Theme’. When I filled in the spaces with my right hand, Ian turned around and said ‘that’s good’. As he was a kick-ass DJ, I just thought ‘keep playing it’. It had this weird bleep sound, which is how the famous melody came about.”

The pre-recorded bass tone was sampled up and used instead of Bahar’s original DX7 bassline. Park programmed the drums, layering hissing cymbals and electro-style hits over a pumping kick-drum. Once Bahar had added the spooky string chords, the track was almost complete. McGill was keen to lay down some lyrics, but time was running out. In the end, they settled on two alternative versions of the same track: “Only The Beginning” – notable for its deeper bass and smoother production – and the rougher, decidedly raw “The Theme”.

500 12” singles were quickly pressed up and credited to Unique 3 & The Mad Musician (the latter was Bahar’s chosen moniker). The record had an almost instant impact around the North of England, and today it’s not hard to see why. With a few honorable exceptions – see the ghostly textures and ragged acid of A Guy Called Gerald’s Voodoo Ray EP released the same year – early British house and techno music stayed remarkably faithful to the Chicago and Detroit blueprints. Records were largely cheap-sounding, sample-heavy concoctions, with little inspiration other than imported Trax and DJ International 12″s. “The Theme” tore up the rulebook, delivering something that sounded like nothing that had come before.

Crucially, its use of particularly heavy sub-bass – unheard of at the time in house and techno music – meant it appealed to both black and white audiences. It was a hit with black teenagers raised on dub soundsystem culture, and made its way into the record boxes of the white DJs and wannabe producers who hung out at the Hacienda, the Warehouse and Jive Turkey. It was perhaps unsurprising that other young producers in Yorkshire began to take note.

One such producer was Rob Gordon, a former soundsystem builder turned audio engineer at FON Studios in Sheffield. When Unique 3 signed to Ten Records, they headed to FON to re-record “The Theme” with additional rap parts from McGill. Gordon co-produced and mixed the re-recording, helping McGill and Park to create an even weightier, warmer bass sound. Gordon hated house music – despite mixing an awful lot of it at FON – but was keen on the Detroit techno sounds he’d heard Sheffield DJs Winston Hazel and Parrot play during their residencies at local clubs. As a bass head, the addition of a sub-heavy bottom-end – as pioneered by Unique 3 and the Mad Musician – appealed to him greatly.

The softly spoken engineer joined forces with Hazel and mutual friend Sean Maher to record their own “bleep and bass” record as The Forgemasters, “Track with No Name”. Importantly, he also persuaded local record shop owners Rob Mitchell and Steve Beckett to launch a label to release it, and promote other local bleep techno talent. Warp Records was born, and bleep had a home. In some ways, Gordon was the central figure in the bleep techno boom. Aside from helping pick records for Warp to release, his engineered, mixed and often co-produced many of the sound’s most influential records – not just for Warp, but also Network and Bassic.

The softly spoken engineer joined forces with Hazel and mutual friend Sean Maher to record their own “bleep and bass” record as The Forgemasters, “Track with No Name”. Importantly, he also persuaded local record shop owners Rob Mitchell and Steve Beckett to launch a label to release it, and promote other local bleep techno talent. Warp Records was born, and bleep had a home. In some ways, Gordon was the central figure in the bleep techno boom. Aside from helping pick records for Warp to release, his engineered, mixed and often co-produced many of the sound’s most influential records – not just for Warp, but also Network and Bassic.

As for Unique 3, they became minor stars in British dance music, creating blends of electro, house and, of course, bleep. By now, Bahar had long since parted company with Park and McGill. He decided to pursue his own projects shortly after the recording of “The Theme”, leaving the Unique duo to become a quartet with the addition of fellow locals Edzy (who continues to record under the moniker to this day) and Delroy Brown.

“After the Chill Records release of “The Theme” things really took off for them,” Bahar says. “They were playing bigger parties, and with Edzy’s help putting on big events with guests from the USA. The more DJing they did, the less time I spent with them as I wasn’t a DJ,” he admits. “It came to the point that we had nothing left in common. I handed over the rest of the unsigned tracks that we’d been working on, and did my own thing. Because I wasn’t much of a clubber I never really understood how important it was, or what it did. At the time I’d heard it was a big track at the Hacienda so went there one night. The doormen wouldn’t let me in! The same thing happened at the Warehouse in Leeds. I just thought ‘I don’t belong here’.”

Bahar still doesn’t quite understand the impact of “The Theme”, which seems a shame. Its unique fusion of simple electronic riffs, punchy drum machine grooves and bowel-bothering basslines spawned a uniquely British take on techno. It was a homegrown answer to the machine music of Detroit created by similarly disillusioned youths in post-industrial cities in the North of England. In the process, British house and techno clubs began to move to sounds forged close to home, rather than those imported from Chicago. For this reason alone, it remains a benchmark in British electronic music.

Matt Anniss