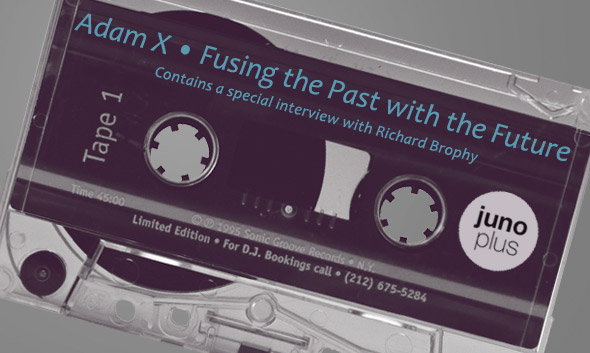

Adam X: Fusing The Past With The Future

Richard Brophy finds the Sonic Groove boss in a reflective, yet typically bullish mood following the release of a second mix of Traversable Wormhole material.

Richard Brophy finds the Sonic Groove boss in a reflective, yet typically bullish mood following the release of a second mix of Traversable Wormhole material.

Adam Mitchell is trying to move on. The Brooklyn born DJ/producer has just returned from his hometown, where he tried to sell off part of his 10,000-strong collection. The plan was to reduce it to a more manageable 5,000 units but in spite of his best efforts, old habits die hard and he admits that the sale was ‘a slow process’.

“I want to keep all the good ones and I’ve weeded out the records I still play, but I had to get rid of some that were taking up space. At the time, I collected all the records on a label, so I have the first 150 Djax Up Beats releases. I also wasn’t aware how valuable Steve O’Sullivan records have gotten, which seems a bit random when you see Primitive Urges records selling for 50 cents.” Now that he’s based in Berlin, does he miss his collection? “Yeah, I would like to have them at home, but I don’t miss carrying them.”

Despite being a Serato user and having fallen out with the record industry a few years ago – more about that later – Adam still places a lot of value on vinyl. It was through this medium that he rekindled interest among the techno community for his productions with the Traversable Wormhole project, which was originally available as a series of hand-stamped, anonymous vinyl releases. However, Adam believes that the situation has changed since the first release in the series in 2009. “When I came out with Traversable Wormhole only a few people were doing that (anonymous techno releases). Now it seems like the market is flooded with vinyl again, and it reminds me of the Prime situation back in the late ’90s, when you had 20 records coming out every week and all sounding the same,” he says.

Mitchell is referring to the glut of loop techno released during that period. The phenomenon was exacerbated by P&D deals, which allowed labels – and labels owned by distributors – to churn out releases with little or no quality control. The situation did not end well, with UK distributor Prime going out of business, followed by Integrale. “When I was running the store (Sonic Groove) in New York, I was getting all these releases from distributors and everything was starting to sound the same. There were probably some great records that I slept on at the time but after you go through 100 releases in one day, you feel brain dead.”

As Adam sees it, the same thing is happening again now, albeit for different reasons. “I still get a load of promos every week and spend time looking for the standout tracks. I go online and do a big search once a month – usually I’m looking at about 300 records and out of that I’ll probably find 50. It’s a lot of work and you never really catch up.” The reason for the glut of techno on vinyl is partly down to the availability of cheap production software, and also because it is relatively cheap to press up small volumes – a key difference to the situation during the late ’90s/early ’00s when higher volume pressings lead to bigger debts. “Yeah, you can do 300 copies for 800 euro – there are a lot of digi labels, but I feel that it is better to put your money where your mouth is and release on vinyl,” he claims.

Adam is also sceptical about producers returning to hard, industrial-themed techno and recalls that many doors were shut in his face when he was doing similar music a decade ago. “It’s done a 360 degree turn; back in 2004, only British Murder Boys were putting out hard techno and the distributors were giving me a hard time. I’ll be honest, I had problems selling records and because of that I became very anti-industry and went digital,” he explains. “My feeling was that they didn’t support me so I’ll play digital and it made me very anti-vinyl. I was playing rhythmic noise and it was really difficult to push what I wanted to. I got really frustrated and it was only when the first Orphx record came out [on Sonic Groove in 2009] that it became easier.”

But Mitchell is still frustrated about what he feels are the dissemination of inaccuracies about the music he championed for years. “You get a writer on Resident Advisor talking about the ‘industrial revolution’. Surgeon has always had an interest in industrial; Sleeparchive has an EBM background and Regis comes from post-punk, but for RA to do an article claiming that it all came from the UK really ticked me off,” he says.

“I mean Ali [Perc] is a friend, but the focus of the article was wrong, they tried to socio-politicise it. The people they interviewed all name-checked the same clichéd influences; there was no relevance about what has been going on for the past 20 years. I mean there has been a really strong industrial scene for the past 20 years. Sorry, sometimes this all gets a bit frustrating.”

It’s not hard to empathise with Mitchell; his adherence to industrial at a time when hamster fart beats and hiccupping effects were popular meant that he became the ‘anti-Christ of the minimal scene’ and saw him banished to a cultural wilderness. This refusal to engage with or support the popular underground music of the day also had a detrimental effect on his bookings. “I went through a period when I moved to Germany and I didn’t get much work. In 2004, 2005 and 2006, I was literally playing for nickels and dimes. I was gigging just for the sake of it, but also because I believed that techno would come back.”

“I could also feel that people wanted classic techno. I mean, you could hear it, Ben and Marcel were playing a lot of classics in their sets, there was something bubbling up.”

Adam persevered through the tough times and found like-minded people who shared his view. He cites Berghain and the club’s residents, Ben Klock and Marcel Dettmann, as instrumental in pushing a tougher sound. “When I started the Traversable Wormhole project, I was going to Berghain a lot and listening to Ben and Marcel playing for nine hours. I heard all these old, timeless techno records and then when I started releasing music [as Traversable Wormhole] I would hear them play it as well.”

When Mitchell started the project, he decided not to include any information on the releases. Was he not tempted to put out the records under his own name or at least make known his association with the project? “No, originally, I didn’t put my name to it because there was too much of a stigma attached to my name – most people probably thought I was an old school rave DJ,” he says. While Mitchell says that he ‘gives everyone a chance, even when they are flooding the internet with music’, he feels that others are less forgiving and he was concerned that any association with his name would have scuppered Traversable Wormhole before it got off the ground.

By way of demonstration, he explains that “there was one club that I won’t name which wouldn’t give me a gig as Adam X; once they had confirmed me to perform as Traversable Wormhole, I told them who they had booked”. While he may have projected himself as a new artist, the delivery method for the music was rooted in late ’80s/early ’90s vinyl culture. “The whole idea about releasing records with just a stamp on them happened after I went to Rubadub and saw all of the white labels on the wall – it was like the releases from back in the day,” he explains, adding that “I could also feel that people wanted it [classic techno]. I mean, you could hear it, Ben and Marcel were playing a lot of classics in their sets, there was something bubbling up.”

Mitchell’s timing was good. By 2009, minimal had become a daft, self-parody for those who were too wasted to care. “People who had moved to minimal shifted back to techno – 2009 and 2010 was a great time,” Adam believes. Unfortunately for every artist who pushes a new development, there are countless followers content to copy them. Fast forward a few years and variations on the type of brooding, bassy tones, tunnelling, hypnotic grooves and repetitive metallic percussion of “Worldwide” and “Universal Time” – which both feature on Volume 6-10, the second mixed Traversable Wormhole compilation on CLR – could be heard everywhere.

At this juncture, Adam decided to unmask himself.

“By this stage, people were following me, so I felt Traversable Wormhole had an identity and there was no longer a need to be anonymous,” he says. It’s not the first time that he has worked anonymously and has worked on other projects, but as these “didn’t create a buzz or get recognition and didn’t sell as well”, he didn’t say he was behind them. He also claims that “there are other well-known producers who have done side projects but have never revealed who they are, which is amazing”.

By contrast, Traversable Wormhole had created a serious buzz and people were beginning to get curious about who was behind it. Having searched online to see what was being said about the project; Adam noticed that German DJ Chris Liebling had mentioned it on Twitter. “I saw him in  Berghain shortly afterwards. We hadn’t met in a few years and one of the first things I asked him was if he liked the Traversable Wormhole records. Here I am showing up out of the blue and mentioning this project, so he twigged pretty quickly.” Adam says he was curious to see ‘the look on people’s faces’ when he told them, but more importantly, he says that “I have never had a plan work out so well. I also guess people thought that I flipped the script when I went to industrial, that I was like a freak of nature,” he laughs.

Berghain shortly afterwards. We hadn’t met in a few years and one of the first things I asked him was if he liked the Traversable Wormhole records. Here I am showing up out of the blue and mentioning this project, so he twigged pretty quickly.” Adam says he was curious to see ‘the look on people’s faces’ when he told them, but more importantly, he says that “I have never had a plan work out so well. I also guess people thought that I flipped the script when I went to industrial, that I was like a freak of nature,” he laughs.

To illustrate this point, he says that he used to get strange looks when he arrived at an after-hours techno party dressed in leathers, combats and boots, even though “I dressed that way, since the early ’90s”. Although his wardrobe remains the same, Adam feels that there are a number of differences between the industrial and techno scenes. “The people at industrial gigs are very supportive and if you play at a 200-capacity gig, 30 people will buy CDs from you – try that in a techno club,” he says, adding that “in industrial, it’s more about artists and live acts, whereas in house and techno, it’s all about DJs”.

That said, there are crossover acts like Orphx and Monolith who have both have remixed tracks from Volume 6 – 10, and Mitchell was also successful in introducing classic hard techno to industrial crowds. “I’d play stuff from the early ’90s like Waveform Transmissions at an industrial night and the crowd would go wild – they didn’t realise that techno was hard, rhythmic music. This is especially true in the US, where the goth, EBM and industrial scenes are all blurred and they are usually stuck together in the same club.”

Adam contends that there is “some good modern EBM” and points out that it’s not as divisive an acronym as that other three-letter word that has dominated American popular culture. Having been one of the country’s first rave organisers, he has ambivalent feelings about the term? “When I was over in New York recently, Frankie was saying ‘EDM’ and I was like ‘can you please not use that term? I mean, my brother and I, we started the rave scene on the east coast, so I don’t want people to think that what we do is EDM. We used to do techno parties for 5,000 people with DJ Skull, Rob Hood and Patrick Pulsinger on the line up. Having said that, when we had our shop in New York in the 90s, we used the term ‘electronic dance music’ as a guide for people who didn’t know the music. Nowadays, I don’t want to be anywhere near those three words – it is sad to say it, but its ideology and music has nothing to do with me,” he states boldly.

Is it not a valid argument that if even a small percentage of Avicii fans get turned on to Traversable Wormhole that it’s a positive thing? “Yeah, I suppose live and let live – New York has a big scene for techno right now and hopefully people from EDM parties will go to events with a little less cheddar in them. Richie Hawtin gets so much flak for playing big EDM festivals, but it’s a pity that US promoters don’t book more proper DJs. I have to give credit to the Paxhau people – they book some commercial stuff but also people like Dopplereffekt and Stingray,” he says.

Mitchell also feels that Traversable Wormhole is the first project he’s fully happy with because running Sonic Groove took precedence over his studio work. “I could have defined my music quicker – I can play old Joey Beltram tracks from the early ’90s, but I can’t say the same about my music,” he admits. “It has a lot to do with the mix-downs, and it’s only since 2005 that I can say that I am really happy with my music.”

Like nearly every other techno producer, Mitchell is now based in Berlin, and he feels that being located there gave him the impetus to make the Traversable Wormhole material. “You get left behind if you don’t stay on top of your game and a lot of the old school guys don’t have the hunger to keep moving forward. Moving here inspired me to keep progressing with the music,” he says. Despite this, he feels that it is important for producers to learn from the past because it provides the background and context for what happens now. “Techno is built on what has happened before – producers are just adding to it,” he believes. “Just listen to something like Joey Beltram’s Places [from 1995] – it still sounds amazing. The difference now is that the sound is so punchy. We are still taking ideologies and ideas from the past, mixing them together and making something new.”

It would appear that Mitchell applies this approach to his own work. While Traversable Wormhole’s sound design is contemporary, there are nods to the menace of ’90s New York techno and the bass pressure of electro – more about that shortly – and the project is rooted in a classic, albeit relatively bleak sound. This is audible throughout Volume 6-10. Tracks like “Subliminal Warp Drive” have the eerie menace of Gotham’s dark techno past as effects mirror the haunted screeches from deep inside a troubled psyche, whereas the pulsing acid undercurrents and bleeping minimalism of “Universal Time” and “Eternalism” could be an update of classic ’90s Sahko/Plastikman minimalism.

“Stylistically, I am still doing the same thing – it’s not too far off from what I did in New York,” he believes, noting that there are similarities between his home town and his current residence. “Both cities are aggressive and have long winters. In New York, there was house, breakbeat, my brother Frankie, Joey Beltram, so many records that set the pace. We can go back further and look at techno – Man Parrish had a track called “Techno Trax” in 1981 or 82 – and there is that debate about Clear, but NY had electro back then too. The press seem to like putting a region thing on the music. It always surprises me that there is such an emphasis on it, people focus on it too much,” Adam believes.

In other instances, like the dubbed out drums, stepping rhythms and cavernous bass of “Centauri Dreams” and “Negative Energy Density”, it sounds like Mitchell has been influenced by his current home. He partly agrees with this assessment, but also cites that the East European broken beat techno of Olga + Jozef/Loktibrada as an influence, which is audible on the stomping, grainy off-beats of “Wormhole Nexus”. So what about the powerful bass that prevails on Volume 6 – 10, be it the booming sub-bass on “Present Hypersurface” or the more streamlined pulses of “Paradoxical Consequences”?

“I like that (broken beat) sound in techno and that’s why I did the tracks like that, but I have always been a big electro fan and that’s where the heavy basslines come from,” Adam explains. “When I moved to Berlin I put on some parties with artists like Legowelt, but it was a tough place to do them because it didn’t have a big following and many Germans don’t know how to dance to electro – it confuses them,” he says.

For Mitchell, where to go next is an issue. With ten Traversable Wormhole releases under his belt and a second CD about to drop, he feels that he’s reached a milestone with the project. “A part of me likes the fact that it has reached ten releases, but I will go where the music goes,” he says somewhat obtusely. In the meantime, he is going to unveil another project, Mass-X-odus, which will focus on ‘hard and heavy industrial techno’. Does this mean the end of Traversable Wormhole? “Maybe the project needs names and not numbers – I am going to keep playing live as Traversable Wormhole and bounce around a load of ideas in the studio,” he says cryptically. “Maybe you’ll see more of that kind of music from me in the future. I like so many types of electronic music; I like to fuse things, a fusion of the past and the future.”

As Traversable Wormhole shows, sometimes you have to take one step back to go three steps forward.

Interview by Richard Brophy

Traversable Wormhole Volume 6-10 is out now on CLR