Leaving a legacy: A discussion with Crème Organization’s DJ TLR

Across its twelve year history Crème Organization has remained steadfastly singular in their approach. Here Richard Brophy speaks to DJ TLR about the label’s genesis and distinct aesthetic, strong links to the historic Bunker label and Crème’s place in the modern online-centric world. A selection of DJ TLR’s personal favourite Godspill art is scattered throughout and we also have an unreleased gem from the Crème archives.

Across its twelve year history Crème Organization has remained steadfastly singular in their approach. Here Richard Brophy speaks to DJ TLR about the label’s genesis and distinct aesthetic, strong links to the historic Bunker label and Crème’s place in the modern online-centric world. A selection of DJ TLR’s personal favourite Godspill art is scattered throughout and we also have an unreleased gem from the Crème archives.

If Crème Organization had been founded in 2012, it probably would have topped all the end of year lists. The reality is that the Dutch label paved the way for much of what is current now, with labels like LIES taking inspiration from it. However, back in 2001 when TLR started the label, Crème was at odds with the prevailing loopy techno and trashy electro-clash doctrines.

This had a lot to do with its founder, who comes from a hard-core punk background, and who was part of The Hague’s party squat scene in the mid-90s. During these hazy days, one name loomed large in The Hague: Bunker Records. TLR says that initially he didn’t buy the Bunker releases because his passion was hard-core punk. Bunker filed for bankruptcy in 1997, and when it came back, TLR says he was “more into the music”. “Bunker and Unit Moebius [I-F and Bunker founder Guy Tavares’ techno act] were very close to home and are very, very important for what we do here. We wouldn’t be here without them – they really are innovators.”

TLR’s links to Bunker remain strong; his mail order operation Godspill acts as the distributor for Tavares’ label – “it’s the only label we distribute, so because we only have one product and they have such low pressings, we just send an email and it’s done.” He also recently did a retrospective podcast of Bunker material, and also says that he helps put up Bunker material on Soundcloud – does this mean that Guy Tavares is not an internet user? “Don’t be fooled, he doesn’t want to be, he’s an unwilling participant, but he’s online every day,” he replies.

TLR is originally from Leiden, a small historic university town in Holland that he says is “a bit nicer than The Hague; the nice parts of The Hague are where the EU officials all live”, but it is the administrative capital of the Netherlands where he spent his formative years, and it is also there that Godspill is based. The mail order business is a partnership between TLR and the artist Godspill, who does the striking artwork for each Crème release, and is going surprisingly well.

“There’s a lot of logistics involved, but the orders keep on coming and we have four people working on it at the moment. I don’t know if it has to do with a general uplift in vinyl or if we are just doing something right,” TLR explains. Given that Clone, Rush Hour and Godspill all have online stores and that Amsterdam has a long list of physical record shops, it would appear that the Dutch punch above their weight internationally in this regard. TLR disagrees.

“There’s a lot of logistics involved, but the orders keep on coming and we have four people working on it at the moment. I don’t know if it has to do with a general uplift in vinyl or if we are just doing something right,” TLR explains. Given that Clone, Rush Hour and Godspill all have online stores and that Amsterdam has a long list of physical record shops, it would appear that the Dutch punch above their weight internationally in this regard. TLR disagrees.

“It’s a rich, industrialised country and it is extremely densely populated – within the space of 60 miles there are about 7 million people. It’s a conurbation, there are a lot of people living here, but if you hired a medium-sized hit squad and took out 10 people, maybe 15 to 20 people at the most, everything, the stores and the labels would collapse. It’s a small scene really.”

He also attributes Crème and Bunker’s longevity to a punk mentality rather than being a by-product of North European industriousness. “The people involved come from a punk background, an 80s DIY mentality, it’s a very strong attitude from Crème and Bunker,” he says. “In the early days, we made a lot of connections with a lot of different people; we were going to the States back in 2001. It’s an attitude that has been very important to Crème, doing low-level parties in squats, doing our own bookings and pressings, avoiding being part of the industry.”

However, it wasn’t just a DIY attitude that allowed Crème and its associates to reach out. TLR’s Global Darkness website gave the label the infrastructure to make the connection with a network of like-minded freaks globally. The Global Darkness name is derived from one of the parties that TLR and his colleagues organised back in The Hague during the mid-90s. “I wanted to do a project with music and the name just stuck,” he explains.

In the pre-social media internet world, the site became a hub for people all over the world to share their thoughts and mixes, with a focus on the new school of electro, Jak and Italo emanating from the Dutch West Coast. “It became a weird sort of community and I still run into people who were part of that underground scene,” he says. Rather than forming an elitist clique or aping the infrastructure that commercial dance music had created during the 90s, GD allowed everyone to join in. “Yeah, it was a club, but the only membership requirement was an internet connection,” TLR recalls. “I didn’t plan it that way, it just happened. You know, sometimes things do just happen like that. It was a bit of swimming in the dark because at the time you didn’t have these super powerful networks and databases – you could create your own hub online,” he adds.

“I am pleased that labels like L.I.E.S have got so much recognition – they are in our corner of the universe, it’s not some German minimal label.”

Like Tavares, TLR has an ambivalent attitude towards the internet. On one hand, he talks about the power of ‘databases’ like Wikipedia and Discogs and how ‘no one could have predicted them’, but on the other hand, Crème has fully embraced social media to propagate its own agenda. While he believes that “everything I do that’s connected to the label is a form of promotion”, TLR marvels at the DIY power of Soundcloud. With over 4,500 followers, Crème’s page fulfils the role of being the ‘official channel for Bunker Records’.

“It’s not like having your own page on Facebook – that is the past. On Soundcloud I can put up archives of old stuff or five minutes after someone has made something, it’s up there. You can put weird music up there, stuff that people wouldn’t necessarily buy or music that you couldn’t sell for legal reasons. Why would you ever go back to MySpace – that’s a version of the internet from five years ago,” he believes.

So why did he start Crème? TLR says that Bunker was a huge inspiration, but the decision to set it up was also a result of his personality. “I’m a restless person and I wanted something, a project that I could completely control,” he explains. “At the time, I was Djing a lot, but I didn’t know where it was going to. I wanted to have something to show, I needed something that was a footprint. I had already been around the block and I didn’t have kids, so I needed to leave a legacy [laughs]….it was a good decision. If you don’t have something to back you up as an artist, it’s rare that you maintain a long career,” TLR adds.

So why did he start Crème? TLR says that Bunker was a huge inspiration, but the decision to set it up was also a result of his personality. “I’m a restless person and I wanted something, a project that I could completely control,” he explains. “At the time, I was Djing a lot, but I didn’t know where it was going to. I wanted to have something to show, I needed something that was a footprint. I had already been around the block and I didn’t have kids, so I needed to leave a legacy [laughs]….it was a good decision. If you don’t have something to back you up as an artist, it’s rare that you maintain a long career,” TLR adds.

Apart from one EP as Mr Clavio for Crème – the production is credited to the label owner and a certain D Blanco – TLR does not produce. Like owners of other great underground dance labels – Zip, Serge and Ron Morelli spring to mind – he has flirted with production but prefers to focus his efforts on A&Ring and representing the label as its DJ.

“I don’t put the time into producing to be able to pursue it as a musical career and anyway, first and foremost, I like to DJ,” he says. “It has become much easier to make shit on the fly, but there is nothing I can get fully behind yet. It would be easy, too easy to put something out on my own label, so I would only be interested in getting another label to release it,” TLR claims.

Back when Crème first appeared, electronic music sounded very different. Techno was choking on its own loopy pomp, house reverberated to the dubby drums of San Fran and there was an existential struggle taking place between fame-obsessed electroclash and Dutch producers like I-F who wanted to disassociate themselves from the Sigue Sigue Sputnik-esque antics of International Deejay Gigolos. Despite such ructions, TLR remembers the early 00s as a hugely exciting time.

“It was extremely positive, there was a huge musical energy in Holland at the time, especially in the West Coast,” he says. “All the major records that define that scene came out about that time, every week there was a huge new release. The producers were at the height of their creativity and I was right in the middle of that whole energy, it was different to the way it is now,” TLR says, before quickly adding that “I have been around the block a few times and there is a new generation of people now, a new fresh movement, a new way of looking at things. That’s the way that scenes go – people leave them and new people come in. You need new blood.”

“I am pleased that labels like L.I.E.S have got so much recognition – they are in our corner of the universe, it’s not some German minimal label. The core of it is so similar to Crème.” It’s hard to disagree with TLR on this final point; 2012 was the year that the ‘outsiders’ became the insiders, with plaudits heaped on operations like L.I.E.S, Trilogy Tapes and PAN. It would be presumptuous to attribute this shift solely to Crème, but there is little doubt that TLR’s label laid the basis for acceptance of electronic music from the fringes.

“I am pleased that labels like L.I.E.S have got so much recognition – they are in our corner of the universe, it’s not some German minimal label. The core of it is so similar to Crème.” It’s hard to disagree with TLR on this final point; 2012 was the year that the ‘outsiders’ became the insiders, with plaudits heaped on operations like L.I.E.S, Trilogy Tapes and PAN. It would be presumptuous to attribute this shift solely to Crème, but there is little doubt that TLR’s label laid the basis for acceptance of electronic music from the fringes.

While Crème was borne from the Dutch West Coast scene and has released music by mainstays like Legowelt, Orgue Electronique and Rude 66, it has also put out Aux 88’s electro, Bangkok Impact’s poppy Italo and Traxx, JTC and D’Marc Cantu’s acid-soaked Jak. It has also released Pussycat’s rude ghetto, Alexander Robotnick’s older material and Beta Evers’s austere “Confusion” alongside random records like Nami Shimada’s 2004 deep house record “Sunshower” and the widescreen ambience of Phocos’ “Glaciers”.

This willingness to release off the wall records was audible on one of Crème’s 2012 highlights, the bizarre but brilliant “Starfighter” by Rude 66’s side project Jagdstaffel 66, which featured a German language narrative about fighter pilots meeting their maker, set to slow-jacking acid-soaked jams. TLR agrees that “there is a general recognition of stuff that has been ignored by the tastemakers for so long.”

Crème has also been releasing albums since the early days, the most prominent of which was also its first, Bangkok Impact’s Traveller. Since then, the label has put out long players by Legowelt, Orgue Electronique, Robotnick, D’Marc Cantu, Rude 66 and David Kristian, but its owner doesn’t differentiate too much between releasing EPs and albums.

“If people come with enough tracks then great, it’s a double 12 inch in a nicer sleeve – the important thing is that it has become easier to promote and at the push of a button we can reach 10,000 people”. Yet while promotion has become easier, sales of vinyl have fallen since Crème launched in 2001. TLR admits that while sales still fluctuate per release, the big change was in 2007 and 2008 when a lot of European distributors like Neuton went down. “There was a drop of about 40% and a lot of labels disappeared – it was a reshuffling of the cards,” he says. Crème prevailed because it has low overheads and as TLR charmingly puts it, “I can eat peanut butter”.

He believes that there are still enough ‘freaks’ out there to buy vinyl, and perhaps surprisingly, for someone who runs a vinyl label, is upbeat about digital, including the possibilities that services like Spotify offers. “It’s hard to put numbers on it, I’m surprised it works well,” he says. “Streaming is becoming a factor; it brings the music to an older audience that might not want to be part of an underground subculture. It also gets the artists on the label exposure and makes them visible. Most of the money comes from doing gigs,” he adds.

He believes that there are still enough ‘freaks’ out there to buy vinyl, and perhaps surprisingly, for someone who runs a vinyl label, is upbeat about digital, including the possibilities that services like Spotify offers. “It’s hard to put numbers on it, I’m surprised it works well,” he says. “Streaming is becoming a factor; it brings the music to an older audience that might not want to be part of an underground subculture. It also gets the artists on the label exposure and makes them visible. Most of the money comes from doing gigs,” he adds.

Creme might be keeping up with digital trends, but they were ahead of the curve when it came to paying tribute to Chicago tracks. In particular, the Creme Jak series offered up a particularly dark, at times brutal vision of Ron Hardy, Phuture and Adonis’ acid fuelled visions. What does he make of the slew of Chicago styled releases doing the rounds?

“I have no idea; I can’t take credit for it, it has more to do with the general zeitgeist. We have been doing it for a while, but there are other labels that do it as well,” he says, adding that “when we released that stuff five years ago, no one gave a shit. I don’t think it’s good or bad. I mean someone doing a Chicago style record in 2001 was already 15 years too late, so being 25 years too late doesn’t really matter much.”

In any event, he is adamant that the Jak series is “terminated” and that “it was a very different thing when it started back in 2007. This was reflected in the response to Jak, which was slightly above zero,” he says somewhat cryptically. “It was a fun series to do and anyway, there are a lot of labels that release in that style now.”

Creme started off with producers from the west coast and like-minded artists, but don’t be too hopeful then if TLR doesn’t check your demo. “Sometimes I go through tracks people send me, but I have never really released a record from a demo,” he points out. “Usually I get releases through referrals and I will listen to them differently. I mean, I might have missed something great that came out of the blue, but I don’t think I missed the Beatles, put it that way.”

In this regard, TLR has the same complaint as almost every other underground dance label owner. “The flow is never ending, it is so random, it often never has anything to do with the label and we already have a very busy roster,” he adds emphatically.

This last statement may come across as elitist, but TLR is keen to ensure that Crème differentiates itself from the mass of homogeneous labels with identikit rosters. “Sometimes I feel that modern A&Ring is just like collecting names – and if you look at some of the labels on Discogs they have all the same artists. It means they lack a certain character and it feels like they [the label owners] are just making lists.”

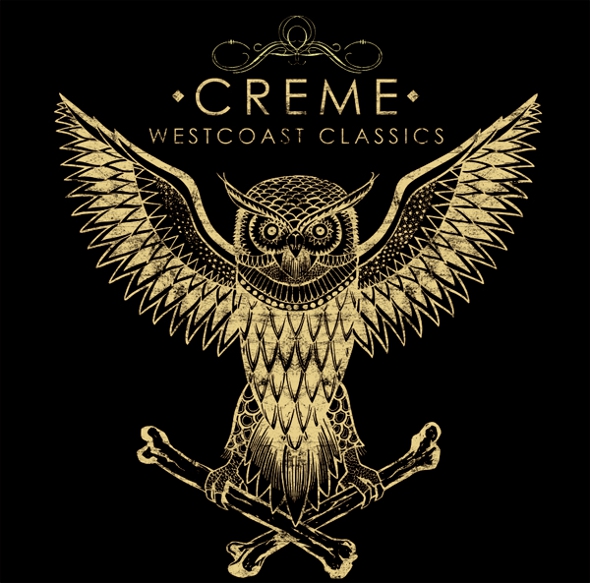

One feature that sets Crème apart from its contemporaries is its surreal, at times disturbing artwork. It’s rare to find a dance label with such a strong visual image, and the inlays and covers, which feature eye-patch wearing, knife wielding school girls, psychedelic owls and Jesus-like characters covered in all-seeing eyes are all the work of one artist, Godspill (who is TLR’s partner in the mail order service of the same name). “He’s been doing all the art since day one,” TLR explains. “Like everything with Crème, it wasn’t planned, we just clicked together, but we agreed that he wouldn’t do art for any other dance label. All of the artwork is drawn by hand – Godspill is a proper artist, an art graduate.”

One feature that sets Crème apart from its contemporaries is its surreal, at times disturbing artwork. It’s rare to find a dance label with such a strong visual image, and the inlays and covers, which feature eye-patch wearing, knife wielding school girls, psychedelic owls and Jesus-like characters covered in all-seeing eyes are all the work of one artist, Godspill (who is TLR’s partner in the mail order service of the same name). “He’s been doing all the art since day one,” TLR explains. “Like everything with Crème, it wasn’t planned, we just clicked together, but we agreed that he wouldn’t do art for any other dance label. All of the artwork is drawn by hand – Godspill is a proper artist, an art graduate.”

The other way that TLR will counteract homogeneity is through his new sub-label, R-Zone, which launches this year. Each release will be by a well-known producer working anonymously and the style of music will be different to Crème. “It will be more extreme, like 90s dubby techno and it will be more about the series than the artist, even though there are some big names involved by Crème’s standards,” he says. “I want R-Zone to be like the old days when you just heard records that blew your mind without any of this ego drama,” he explains.

This doesn’t mean that Crème will be sitting it out in 2013 and TLR says that it has 12-15 releases ready to go from Willie Burns, Xosar, Alex Israel and Soul Force as well as an album from Neville Watson and the ‘usual suspects’. They may be outsiders, but expect Crème to rise to the top.

Interview by Richard Brophy

Creme label art by Godspill

Header image by Ilaria Pace from a photo used courtesy of Alexey Smolin