Dial it in until it feels true: An interview with Bass Clef

At this point in time the notion of house music in the fallout from dubstep’s megaton blast is a tenuous one, as slews of producers defer from their allegiance to 140 and turn out variable results in 4/4 grooves. Undoubtedly some wonderful music has resulted, fusing heavier bass with more rigid rhythmic constructions, but of course hype and trend dictate that a lot of disposable offerings will make their way through as well.

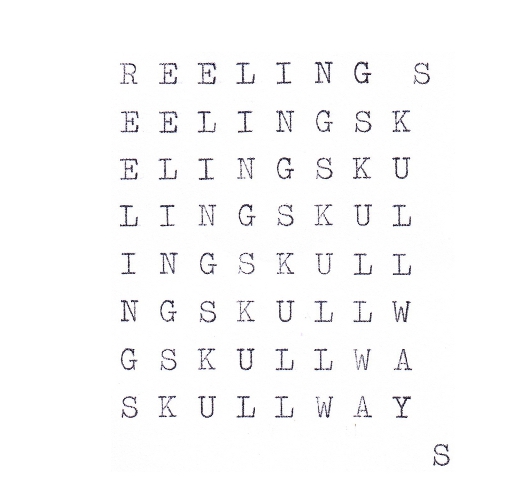

In that sense, it came as something of a surprise when Bass Clef unveiled his Reeling Skullways album, with the London-based producer explicitly embracing slower tempos and distinctly house-derived drum patterns. However, it would be impossible to argue that Ralph Cumbers has ever followed any kind of suit in his musical career to date, veering as he has between different distinct album studies and a wealth of side-projects and aliases.

If his past achievements weren’t enough reassurance, one listen to Reeling Skullways is all that is required to understand that Ralph’s take on house music reaches far beyond obvious tropes and predictable structures. In the living, breathing hum of his computer-less compositions the standard rules don’t apply, and instead you find yourself flung into a world of sci-fi strangeness and starry-eyed wonder. It’s a sensation that can, in spirit at least, be likened to the effect Phuture’s revolutionary “Acid Trax” had when the alien intonations of contorted machines first reached people’s ears. “When I first heard acid house, it was acid in the psychedelic sense of the word,” Ralph explains as we press him on the transcendental nature of his recent output. “It’s very trippy music, I always liked that edge of it.”

Experiencing the nascent rave sound as an impressionable 11-year-old, the likes of chart-toppers such as Altern-8 and The KLF gave Ralph his gateway into the world of electronic music. Drum & bass first stole his heart as a teenager and gave him his formative raving years, while the time he spent in Bristol proved constrictive towards an embrace of house and techno. “When I was DJing a lot in Bristol,” Ralph reveals, “if you ever played something with a 4/4 kick everyone would leave or go to the bar.”

Likewise, Ralph was less concerned with creating music in that realm. From his breakthrough debut album A Smile Is A Curve That Straightens Most Things through to the Africa-infused rumble of May The Bridges I Burn Light The Way, the half-step rhythm remained king for the most part, albeit twisted to different ends from project to project.

“When you deal with 4/4 you stop thinking about the boom-bap of hip hop which is in a lot of half step,” Ralph explains, “and it frees you up to start thinking much more about swing and layers of percussion. I’ve always instinctively avoided melody and harmony because I don’t think I’m very good at it, but moving to 4/4 made me stop worrying about where I was putting the kick drums and snare drums as I had done before and started focusing on other aspects of the music.”

There’s a lot to be said for artists with enough conviction to press on forwards rather than sticking to safe bets and familiar territory in their music, and Ralph readily acknowledges that each of the five albums he has released has represented the undertaking of a new challenge or a further step outside of his comfort zone. It may seem somewhat surprising to hear him talk of melody and harmony as being a weak area, as his productions over the years have always brimmed with an effervescent musicality that many of his moodier peers shied away from, but there is a noticeable focus on Reeling Skullways towards rich, developed melodic content. This is perhaps no better exemplified than on the stunning album closer, “Ghost Kicks In The Spiral”, where thick wads of synthesiser pulse to the side-chained beat of an inaudible kick drum. With the removal of the beat from the equation, it demonstrates just how far Ralph has pushed himself to embrace melody in his latest output.

“When I got my modular synth three years ago I wanted to just make really weird noises with it,” Ralph admits when talking of the key source for the musical elements of his current sound, “so I haven’t put one together that’s very good for making melodies. I haven’t even got a keyboard for it, so I’m pitching the notes using these knobs which aren’t really designed for carrying pitch information, and you end up with a lot of these melodies which are a bit wrong.”

Interestingly, this awkward method draws a parallel with the instrument that perhaps scored Ralph the most attention when he first emerged with his live set. “The trombone is essentially a micro-tonal instrument,” he points out, “so I’ve always been interested in the notes between the notes and how you can play with that.”

After embarking on the engrossing path that is modular synthesis, Ralph kick-started the Some Truths project, which provided a platform for him to delve into his new studio hardware and explore the depth and breadth of sounds that he could muster from it. As you might imagine, the infinitesimal parameters which can be manipulated in such a set up encourages protracted studies rather than the immediacy of more club-ready tracks; a fact which has bled across to the Bass Clef material.

“I used to be able to write something and it would just be four, five minutes long and I wouldn’t have to do any editing,” Ralph laments, “but I don’t seem to be capable of doing that any more! I wonder if it’s working with the modular, because that lends itself to these very long tracks. I always really envy people who can just write three or four minute tracks.”

It’s quite striking how Ralph approaches the writing aspect of his music, compared to the laborious point-and-click culture of purely software based production. Every track Ralph makes is born out of a one-take live jam recorded onto a four-track tape recorder, after which it gets run into Sound Forge for editing. It’s a method that rings true with the wayward duck-and-dive of his song structures, capturing the pressure, energy and excitement of the instance in which the track is recorded.

“I don’t really do any overdubs any more,” Ralph states. “Normally the point when the track’s ready to record is when you’ve run out of cables, or there are no more effects pedals to plug in. I think to myself, ‘right, I can’t add anything else, I better get it down on tape’.”

With the cohesive quality of Ralph’s albums and general release arc, when trying to picture his studio activity it seemed as though he might strike upon a choice set up and run as many ideas through that configuration of equipment as possible. “I’ll be focused on a particular piece of gear or a couple of pieces of gear at any given time,” he explains, “but for every track everything’s unpatched and you’re starting from scratch every single time.”

While it’s easy to hear the presence of the modular looming heavy on Reeling Skullways, it’s surprising that there wasn’t a more rigid template within which the whole album was crafted. Certainly, boundaries are a device that Ralph happily admits to embracing in order to achieve his goals. “The way I work is all about setting yourself these limitations and pushing yourself against those as hard as possible,” he proclaims. “That’s why I’ve never got on with computers, because there’s too much choice. I like to make a decision, move on from that decision and deal with the consequences. I can’t remember who said it, but there’s nothing more terrifying than a blank page.”

Much has been made of Ralph’s methods, from his production to the presentation of his music. If ever there was a champion of cassettes, it would be him. His Magic + Dreams label deals solely in tapes, while his Eckoclef project with Ekoplekz was borne out of sending a tape back and forth to record new tracks onto, before it too got released on the venerable format. His live set is noticeable for the lack of a laptop, and his processing chain at home does much the same. In era where such ways are fetishised, from an arguable resurgence in vinyl to the idolising of classic drum machines, Ralph does wind up getting interpreted as something of an analogue defender.

“It’s not like I live in a hut on the side of a mountain, sending out smoke signals,” he laughs. “I use a computer every day, even the modular’s got digital modules in it. I think from the music that I’ve made and the questions I get asked in interviews it’s always like I’m some massive militant maintaining that analogue is the best and we must all smash our laptops. They both have great things to offer, and just because digital arrived doesn’t mean that analogue should be left behind. I don’t want to choose tea or coffee. Sometimes I want to drink coffee, sometimes I want to have tea!”

All analogue-versus-digital debate aside, that aforementioned distinction between Ralph’s albums and projects, not to mention the prevalence towards long players over singles and EPs, speaks volumes for the constrictions both practical and conceptual that Ralph likes to place on his work to reach a satisfactory conclusion. “I really like albums as a way of consuming and experiencing music,” he explains. “I guess to other people it sounds like I change my style a lot, but I don’t see it like that. I’m just trying to get this self-contained little sound world out that you can sit down and listen to in one go.”

Scanning though interviews conducted with Ralph in the past 12 months, he was intimating on numerous occasions that there was a project in the works which had been building up for quite some time, seemingly at odds with the impulsive one-take wonder that has just thrown down the latest Idle Hands release or the rave-tastic sunshine tones of “Rollercoasters Of The Heart”. Judging by the time frame, surely these hints were foretelling Reeling Skullways? As it happens, the whispers turned out to be a little premature and the album in question was shelved after a year’s worth of development.

“It was really too ambitious,” Ralph admits of the missing project. “It was quite a lot of layers and live instruments, which I would have had to go into a proper studio to do and no-one was going to give me any money to do that. I got a bit lost in it, it was quite an intense time in my personal life, and then one day, I thought ‘fuck it, just put it away’.”

It’s a fascinating concept from the perspective of a non-musician, as to how you could invest so much time and passion into something only to reach breaking point and walk away from it. The album started at the point where Ralph had decided to go full time with music, aiming to work office hours and increase his proliferation in the studio. However it was an ethic that didn’t sit comfortably with him, perhaps leading to the inevitable conclusion of a scrapped venture.

“How it goes for me is protracted periods of doing a little bit here and there and not really getting anywhere and feeling massively frustrated about everything,” Ralph reveals of his more typical cycle in the studio, “and then suddenly one track will come along and then it’ll be a very intense couple of weeks where I’ll work crazy 16 hour days or whatever, until that burst of inspiration runs out.”

The end of the album-that-never-was era marked the start of the most recent surge of material from Ralph, as one of these creative waves rose up and took hold, resulting in one of the most unabashed and joyous releases in his back catalogue. “Immediately after shelving that album that I felt much better about everything,” says Ralph, “and that’s when I wrote Inner Space Break Free. It came out very quickly after this long period of grinding away very slowly.”

As ever, there’s a purposeful thought process behind the whole album (which incidentally was released on cassette only with an MP3 download link for back up), and it’s not hard to surmise the vibe from even a cursory listen. As the grinning familiarity of tracks such as “I Think You Are Ready For The Eternal Point Of No Return” comes whizzing past you like the flash of a strobe in a darkened warehouse, you can almost hear the steam being let off from Ralph’s beleaguered imagination.

“That whole album was a bit backwards looking I suppose, but there’s something interesting about your memories,” Ralph starts, keen to impart his motives behind creating an album that deliberately embraces well-worn devices from the rave age. “You think of your memory like a camera that records the things that happened to you, but it’s much more changeable. Memories are different every time you remember them, so the album is all about that process of trying to evoke them through sound by using a lot of very obvious samples with a lot cultural baggage and signifiers. Drum breaks that you’ve heard a million times before, stabs and noises from tunes, and just trying to use them to evoke the shapeshifting nature of your memory.”

There’s undeniably a rose-tinted view that runs through Inner Space Break Free, no more apparent than on tracks such as “Memory Closer”, which sounds like a wistful, romantic gaze upon a rave from afar. As Ralph would have it though, “that one really is more like walking home after you’ve been at a club all night and there’s music playing in your head, rattling around from the night before.” It’s a sensation many can relate to, and it raises an interesting point about how Ralph treats the consumption of his music. The developed concepts and heartfelt intentions have a healthy consideration for the listener, not so much forcing a reaction or impression on his audience, but certainly hoping for one in a scene that has largely sought to avoid anything so defined. Many electronic producers revel in abstraction and ambiguity on all levels, but Ralph comes across as someone who knows what he’s reaching for.

“I think most music isn’t emotional enough,” he states emphatically, when it’s suggested that at times the temperament of his music exists in a nebulous nether-mood. “I’m not trying to be emotionally ambiguous, I’m trying to be as emotionally specific as possible within the music, but there’s this world of emotions that aren’t easily expressed. Most mainstream pop music is obviously very happy or very sad, whereas most dance music is generally euphoric or rude, in a drum & bass sense, or strangely moody, but the power of music is that it can evoke these emotions that are too complicated for words. That’s the area of music that I’m interested in.”

It’s another example of the purity and honesty with which Ralph approaches his craft, attaching meaning without falling into pretension. Coming back to the original point made in the very beginning, his move to start releasing 4/4 driven tracks is not as a contrived reaction to popular motions in dance music, but as a continuation of the impassioned curvature that delineates his career to date. You need only look to his multitude of other projects, from the nostalgic tape edit series as Coseph Jonrad to his part in the improvisational outifit Snorkel, for further affirmation.

“I try as much as possible not to be influenced by what’s going on around me musically,” Ralph states to draw a line under the debate. “I don’t purposefully sit down and say right, make a house track or make a dubstep track. I don’t look at the bpm on the drum machine most of the time to be honest with you, maybe I should. I just dial it in until it feels true.”

Interview: Oli Warwick

Photos: Tom Medwell

[nggallery id=12]