Marc Kinchen: Under and Over

Marc Kinchen occupies a singular space in electronic music lore; on one hand he is revered by two generations of producers and house music aficionados, and on the other he has carved a lucrative career as a producer for a cast of pop musicians ranging from the risible to the revered: Diane Warren, Snoop Dogg, Pitbull and Will Smith to name just four.

His early – and often overlooked – career in Detroit included collaborations with friend and mentor Kevin Saunderson, before a move to New York in the early 90s saw him rise to fame alongside Kerri Chandler and Masters At Work, pioneering the city’s house and garage sound. His underground pedigree is undeniable: Julio Bashmore is one of many DJs still dropping the MK dub of “Freakin You” to wild shrieks, and earlier this year Omar S reissued 1994 classic “Given” on FXHE.

Indeed it’s difficult to underestimate Kinchen’s influence: Todd Edwards, known to many as the godfather of garage and a hero for producers on both sides of the Atlantic, is quick to credit Kinchen as a key influence in developing his sound. A true innovator of the dub mix in house music, his distinctive basslines and mastering of the cut-up vocal melody ensure MK dubs still burn brightly in 2011. Following a recent DJ tour of Europe to promote his new label (launched in conjunction with his brother Scottie Deep), we thought now was the perfect time to catch up with a certified house music legend.

You’ve had a couple of reissues this year I want to talk about. There was the Defected reissue of “4 You” – how did that come about?

Well, Defected bought some of my old catalogue a while back. They’ve been sitting on it for at least three or four years; I’m not sure what was behind the timing of it (to release the 12” this year).

I thought it was fascinating that you also had one of your early releases reissued on Omar S’s FXHE label this year. When did he approach you to license that track?

That one came through my friend Kai Alce, who approached me. I met (Kai) through Chez Damier, and he was saying, Omar S wants to license one of your records, and I was like, yeah OK.

Was Omar S someone you were following at all before he got in touch?

To be honest, not really.

Omar S is a bit of a modern day Detroit icon in house music circles.

Once I left Detroit I stopped following what was happening there, music-wise. But then people like yourself said, oh that’s really cool that you’re on FXHE – and I’m still a bit like, oh is it? (Laughs)

You grew up in Detroit before moving to New York and then L.A. – do you still feel an emotional or musical attachment to the city?

The thing is, I didn’t even feel an attachment to the city when I was in Detroit. I always felt like an outcast. Even though I worked a lot with Kevin Saunderson, my sound was not really techno, especially compared to what Kevin, Derrick and Juan were doing. I think I stood out like a sore thumb.

In that respect your music is really a blueprint for the early NY house and garage sound. It’s not really associated with Detroit at all.

No, exactly.

You cite Kevin Saunderson as a mentor – how did you first meet him and how did that relationship develop?

I met Chez Damier first – he was Kevin’s A&R at KMS Records at the time. During that time KMS put out a Detroit techno compilation, and they licensed this track I did called “First Base” – one of my first 12 inches. Chez got in touch with me and we talked. I was a kid – 17 – and I didn’t know too much about house or techno, but when I heard a track I could pretty much make something that sounded similar to it within a few minutes. When Chez saw that, he put me in touch with Kevin.

What happened from there?

We went into the studio together. There was a song called “Mine”, I forget who by – perhaps it was Reece – which I worked on with Kevin. We worked on a couple of remixes together; one of them was Evelyn Champagne King’s “Shame”, but most of the time Kevin just let me use his studio.

Was that your first experience in a full studio?

Yeah but I had already been dabbling; I started at 14, using synthesisers and sequencers and drum machines. I used to love Depeche Mode – all that kind of music that was dominated by synths. I was intrigued about how they made those sounds. I used to sleep with a picture of a Juno 106 (laughs), and my dad bought me one for my birthday, and from that point I got more and more into it. Every month I’d buy Keyboard magazine, and try to get equipment any way I could.

So with those first forays into electronic music, what kind of stuff were you making?

I think it’s the same with any young producer – the way you learn is by trying to copy someone else. You hear a song you love and try to make something just like it, thinking, ‘How do they make that bassline?’ ‘How do they program those drums?’ I did that all day, every day, so by the time I was 17 making a track was nothing, it was easy.

What brought about the move to NYC?

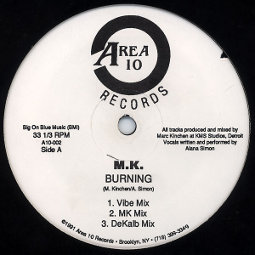

I had just put out “Burning” and I had a girlfriend who lived in New York, we were having a long-distance relationship. “Burning” had been picked up by Cardiac Records, and that prompted the move. I didn’t have any money when I went to New York, I just took some clothes and pieces of equipment.

How did things progress from there? I read in one interview you were knocking out 3-4 remixes a month at one stage in the 90s, when you were based in New York.

I was trying to figure it out on my own for the first six months. I literally had no money – I was borrowing cash from my girlfriend. Then I went to see Marci, who was managing Kevin Saunderson. I took her a copy of “Burning” and a shopping bag full of other records I had, and asked if she wanted to manage me. She said yes, and from there I was commissioned to remix “Happy Head”. I did that mix, it had a bit of an underground buzz, and from that she was able to get me more remix work, and then it snowballed.

“A lot of times I’d be given shitty songs to remix, so I would cut them up, use pieces of the vocals and at least try to give it a melody that I liked.”

People still go crazy over your cut up vocals and basslines. How did you develop that style?

It came naturally. Every once in a while I’d hear a record with a cut-up vocal piece, and I was always interested by that. A lot of times I’d be given shitty songs to remix, and I’d think, I can’t make this good (laughs). The vocals are awful. So I would cut them up, use pieces and try to make them cool, and at least try to give it a melody that I liked. There were some terrible cheesy pop records; even “Happy Head”, those vocals were pretty bad.

You tapped into the fact that the human voice can still resonate emotionally, even when you don’t know what is being said.

Well, people in Japan like American music and they don’t necessarily know what’s being said. There are songs in different languages that people love but don’t understand; it doesn’t have to make sense. How many times do you hear a song in English, and you can’t understand what they’re saying anyway?

I read that sometimes you would knock out a remix in 30 minutes – is that true?

In a perfect world, that’s what I would do every time. A lot of the MK and 4th Measure Men records – some of the best records I’ve done – were one take, done in a raw style…

You’ve got such a massive, sprawling discography, especially when it comes to remixes. Are there any productions and remixes you cherish most?

Recently I’ve been listening to a lot of my older stuff and I’m surprised about how good they sound – not mix-wise, because I was never a good engineer – but the elements still sound surprisingly good, to me at least.

Fans name check your Nightcrawlers remix as a seminal MK moment– what was your big one?

It definitely wasn’t Nightcrawlers; there was a year when a mix came out every week, or at least it seemed like it. It’s all a blur; there was a mix of Jam & Spoon that I did, and it was a dub, and I listen to it now, and I’m really happy with it. But to be honest it’s hard to pick out just one that I remember above all else. I don’t have one all-time favourite mix; there are six or seven that I really cherish.

When did you decide to take a break from house music?

There were a couple of reasons. I wanted to be a pop producer, and I couldn’t do that in the 90s being an underground house producer. So it got to the point where I felt I had to make a choice, and I wasn’t influenced anymore by anything that was coming out in terms of house music. The sound, the scene, started to change. The club scene wasn’t the same – hip-hop was taking over – Jay Z, Puffy, those guys were becoming big, so a lot of house clubs were moving towards hip-hop. I just wasn’t into it as much, and since I didn’t DJ, I was stuck in New York with Puffy (laughs). And when the remix commissions did come in, everyone just wanted something that sounded like Nightcrawlers. I was burning out, so I stopped.

At this stage had you been DJing at all?

No, just producing. I had turntables, I had records, but within five minutes I’d be inspired to get back to producing. Plus I was making so much money remixing, why would I want to go and DJ? It never turned me on.

How did the move to L.A. come about?

I stayed in New York for three more years after that, but I kept going over to L.A. for various reasons. Eventually, I thought the time had come to move to LA. I ended up working as Will Smith’s producer for four years. That’s one of the reasons why I wasn’t heard from for a while; I mean Will paid me well and I didn’t need to do anything else. He built me my own studio, but Will wasn’t really doing anything that was getting released. He worked on one album and it didn’t really do anything, so I was making tracks for nothing, really.

Were you tied to working with Will for that time?

I was non-exclusive, I could have done other things, but I didn’t know that nothing was going to come out of it. I was thinking, I’m working with Will Smith, I don’t need to go out and producer for other people. At that time Will had just sold like a zillion records for Men In Black, so I was thinking I’m going to help him sell some more. But nothing came out of it.

You did do some interesting projects while you were working with Will, like film scores, right?

I did music for Shark’s Tale, I did the theme music for All Of Us. But those projects weren’t exactly satisfying.

And before this you were working Quincy Jones’ studio?

Yeah, that happened in the late 90s. I had a meeting at Motown Records – a friend of mine was A&R there. I went for a meeting one day and I was wearing a $20k Rolex watch – I was getting so much money from remixes, I didn’t know what to buy. And this guy called Jay who was working for Quincy was sitting in the lobby; he looked at the watch and asked, “what do you do?” I said, “I’m a producer…” and I purposely didn’t tell him I made house music – I felt at that time the R&B world looked down on house music. I gave him some CDs, and he took them home to California, and it turn out he worked for Quincy. Because I was doing house for all those years, when I produced my own R&B stuff it had a bit of an edge. It wasn’t typical, not the same as what everyone else was doing. I had hard drums, not too chordy, it was just a bit different. The next day I got a call and they said Quincy wants to give you a deal, so I flew out to L.A. I went in the studio with Quincy, and I started producing pop records. I worked with Snoop Dogg, you know, people like that.

Moving from house music to this – how did it feel?

Well, the whole time from 1990 I was making pop music, on my own, in my room, practising. That was the direction I wanted to go. It wasn’t like I was just learning how to make that kind of music, I always knew how to make it.

How did your approach differ from making pop to house?

I was writing full songs. The thing is, since I wasn’t a DJ in the 90s, I never really knew the kind of impact MK had. I didn’t see a need to go back and do house music – I didn’t think anyone really cared – I just thought I had a nice run where I was getting hired to do remixes. But then when the internet came along, I started reading things, I was getting emails from people, and it made me think. I started seeing what was happening in other countries. If I’m not DJing and I’m not travelling, how could I know? I knew from my friends that I made good house music – Kenny, Louie, Chez – people like that – but I just thought Nightcrawlers was a big record, and that was it. I didn’t know there were MK fans out there.

And what happened after you finished working for Will Smith?

I was trying to figure it out all over again. I still wanted to do house, but it wasn’t the right time. I had eight years in the pop world, and I would’ve remixed pop people and they probably would have been thinking, what the hell is this?

You knocked out a remix of Celine Dion too – how did that come about? And did you ever get any feedback from her?

Well the guy who hired me to do the mix, he loved it, and I knew a few others who liked it too, but I never heard anything back from Celine. I thought that was weird, because it was her only number one dance record. But after Will I was producing songs here and there, and then I started working with Diane Warren. But with Diane, she would write songs and I would produce them, and that was so unsatisfying. Diane is very, very poppy, and I’m not really like that, and I ended up doing some songs that were just so cheesy. And then I heard a Pitbull song with a Nightcrawlers sample. I thought they were mixing Nightcrawlers with Pitbull; a couple of weeks later I found out that was the actual record. From that point I got in touch with Pitbull, and I spoke to his A&R person, and it turned out he had all my house records. From there I started working on everything with Pitbull.

“There was a year when a mix came out every week, or at least it seemed like it. It’s all a blur”

So when exactly did you begin working with Diane?

That was 2008. Diane was Diane; to her I was just her demo producer, she didn’t know anything about my past, nothing at all. I was just a regular guy. And even when I did do a song for her, I didn’t get publishing; she wasn’t sharing that. But the funny thing is, as soon as I started working with Pitbull, Diane was calling me up, saying I have to hook her up with him.

These days you’re working with Will’s daughter too?

I’m in the studio everyday working on Willow, and Will’s two sons. These days I’m at his house two or three times a week.

You’re respected in underground and commercial circles for your work – a rare position for anyone to hold. Why do you think that is?

I just think it’s the way I do business as a person. I’m not the greatest producer at all, but I’ve gone from Quincy Jones, Diane Warren, Pitbull and back to Will Smith with his kids. That’s probably what I’m most proud of; nobody thinks my house music is too cheesy.

You seem to be reconnecting with the house music world – you’re DJing around Europe, you’re launching a label with your brother Scottie Deep. Why now?

For a long time people have been telling me that my sound is coming back in. In the mainstream eyes, it’s cool to be making house. In that respect I can come out of hiding. It’s a cycle; people have heard enough screaming synths, they need to hear a bassline.

Have you been making any house stuff recently?

I haven’t been in recent months, but since I’ve been in the UK and DJing, I’ve noticed there are certain records of mine that still work, the basslines I make in my sleep – they really work. So I feel like I can go back to it; I can just do MK. I’m ready to get into it now. I’m hoping to have a couple of records done before I finish the tour.

What does the future hold for Marc Kinchen?

I made a goal for myself; to have a record in the pop charts and the dance charts at the same time. A true pop hit and a proper house record – I’m not sure anyone has ever done that.

House Masters by Marc Kinchen/MK will be released on November 14 via Defected Records – check it out here.

Interview by Aaron Coultate