Martyn: Location, Location, Location

Electronic music is inextricably linked to urban settings. From Detroit’s post-apocalyptic downtown to the tower blocks of London and Den Haag’s faceless monuments to Eurocracy, the city location is the natural habitat for bass, techno and even the irresistibly wry reapproximations of Italo and electro.

It should come as no surprise then that the grey area where dubstep and techno meet is an urban one, be it the faded grandeur of Berlin or the concrete conurbation of Rotterdam. Indeed, Holland’s biggest port didn’t just spawn the Clone mini-empire but is also the hometown of 2562 and the birth place of 3024, the label set up by long-serving Dutch DJ Martyn and visual artist Erosie, who provides the sleeve artwork for each release.

It was from this sprawling megalopolis that Martyn aka Martijn Deykers’ delicately weighted combinations of fractured rhythms, techno soul melodies and touching melancholia emanated, with 2008’s “All I Have Is Memories” and “Natural Selection” catching the attention of techno, house and dubstep DJs.

However, in the same way that big cities’ demographics are transient, there was an impermanence to both Martyn’s artistic caprices and his own personal situation. For the past four years, Martyn has been living in the US in relative obscurity in Washington, making music that is nudging ever closer to a purer form, while retaining his own nuances.

“I wasn’t sure if today was my wedding anniversary, so I looked up my marriage certificate and yes, I’ve been here for four years,” he says, laughing nervously at the prospect of forgetting to mark he and his wife’s big day. Despite his personal and musical background, Martyn easily embraced his new surroundings and in retrospect, is delighted that he made the move to the US.

“I didn’t choose to move here for musical reasons, and apart from the odd hurricane, it’s great,” he says of his home. “I grew up in Eindhoven and then I lived in Rotterdam. It still feels like the centre of things, but I like the remoteness of where I am now. There is nothing that reminds me of the scene here and that’s a good thing. It keeps you fresh.” Now that he is no longer at the epicentre of things, Martyn feels that a little bit of distance has boosted his creativity.

“You can get inspired by a certain sound, but the danger is that you can sound too much like other producers if your are around them,” he says, before adding that “it’s different for everyone. I have friends who live in the UK and who never go out and are only influenced by the internet. Being away from the centre helps me because I go to Berlin and Rotterdam, get inspired and come back home to make music.”

Transatlantic travel doesn’t appear to bother Martyn either, and he has a well-practiced routine to make the journey as painless as possible. “The airport is nearby so I leave the house two hours before the flight and it takes six or seven hours to get to Holland or Germany,” he explains. “I see all of these people at the airport about to embark on the trip of a lifetime, but for me it’s just like taking the bus. I arrive with a weekend bag and before you know it, you’re in Europe.”

Martyn’s wife also accepts that his chosen profession requires him to regularly traverse the ocean and is supportive.

“She knows about my lifestyle and when we first met, we were going to clubs together. She has seen the inside of most clubs and it isn’t interesting to her anymore unless it’s somewhere new or special,” he says.

While Martyn’s existence nowadays consists of a care-free life in a remote part of America, he hasn’t forgotten where he’s from. With the exception of the techno city state of Berlin, it’s hard to think of any other continental location that has yielded so much pioneering electronic music as Holland. From the deep, often abstract techno of early Sterac, Speedy J and Stefan Robbers and labels like Eevo Lute and 100% Pure through the sexy US house of Outland Records and the nu Italo and Chicago jack meets electro sounds pioneered by I-F, Legowelt and Alden Tyrell, Holland can also lay claim to two of the world’s leading 360 degree electronic music operations – Clone and Rush Hour – encompassing stores, distribution and labels.

When Martyn and 2562’s contributions are included, it looks like the country has given the world a huge amount electronic music relative to its size. Why is this?

“It’s probably a combination of lots of different things, but it’s also location. It’s a small country and we are always looking outwards. We did it back in the 17th century with our ports and we are still trying to connect the dots with lots of other places,” Martyn explains. “Holland is like a mix of things and people, unlike, say, France. Holland has changed a little in recent years, not so much in the musical sense, but more in its liberal way of thinking. But in the past it was one of the places that invited foreign DJs to come and play – Derrick May and Juan Atkins even moved there and were inspired to make music there.”

Despite its reputation as an electronic music hub, Martyn says it wasn’t easy for him to gain recognition there. “The respect for Dutch artists isn’t big at home and it’s something I experienced,” he states baldly. “It was very difficult for me to get gigs or any kind of acknowledgment at home, but as soon as I moved somewhere else and got established there, I was immediately recognised at home!”

But isn’t the same in every country? This writer has heard accounts from French producers that tally with Martyn’s experiences, while in smaller European countries like Ireland or Belgium, anecdotal evidence suggests that upcoming artists face similar obstacles. Martyn disagrees and cites the UK as an example of a country that supports its own artists and provides an infrastructure for their development. “People who want to do something in music in the UK get a lot of support from the ground up until they get much bigger – only when they’re really famous that they get taken down in the media,” he laughs.

“Americans have a very positive attitude, they always want to do things, achieve things and I’m really inspired by that, by the American dream”

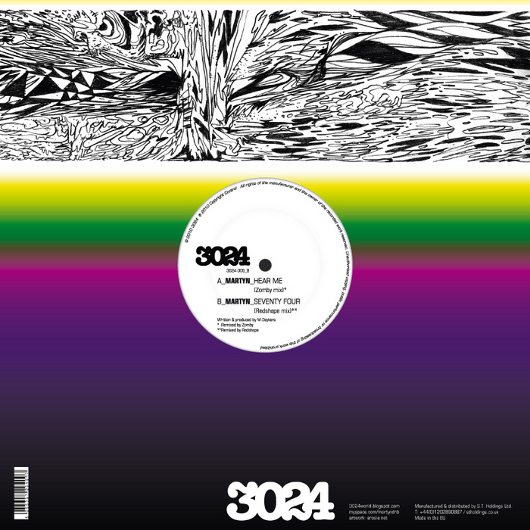

Perhaps due to a lack of support at home, Martyn and his long-time friend Erosie decided to set up the 3024 label in 2007. As Martyn explains, the label is “a reference to the place in Rotterdam where we lived” and they both felt it important that 3024 acted as “a starting point”. “It’s where Erosie’s art started to be taken seriously,” he adds. Now that he has re-located to the US, surely the same urban influences are not as prominent?

“Yes, the place I live in now is a lot less urban, but I’ve learned a lot about people and culture here,” he believes. “Every time that you take a step out a place you learn something and the US is not like Europe; I learnt more about Dutch people living in the US than I did living in Holland.” So what has he learned?

“I myself am not so cynical anymore and America is not such a cynical place as Holland,” he adds. “Americans have a very positive attitude, they always want to do things, achieve things and I’m really inspired by that, by the American dream, that things can happen. It’s a nice attitude to be around, much nicer than sitting around in a room full of people saying ‘everything is going to hell’.”

The American sense of looking into the future, a sensibility initiated in Detroit techno and then subsequently interpreted through a European prism, has also shaped much of Martyn’s output, audible on breakthrough releases like “Memories” and “Velvet” as well as on his new album, Ghost People – more about that later.

Originally a clubber who danced to the sound of early Detroit techno and Chicago house, Martyn believes that the same sensibility has informed every subsequent step he has taken, both as a DJ and producer.

“The general sound I’ve always been into, not matter whether you call it techno, drum and bass or dubstep, has a lot to do with futurism and musical layers. It’s part of my musical DNA,” he feels. “When I got into drum and bass in 1994 and 1995, it was artists like Goldie and Photek, who used a lot of samples from Vangelis soundtracks. My feeling for this type of music has more to do with that palette of sound than the tempos or beats,” he says. Of course much of this music is made in urban environments, and Martyn feels that there is a tendency to “look towards the future as a place that isn’t happy – that’s what this kind of futurism comes from”.

Clearly, the introspective side of electronic music has impacted on Martyn’s new album, and these influences can be heard, alongside the experiences gleaned from his frequent transatlantic jaunts. Ghost People is a techno work in the broadest sense: containing echoes of 90s rave/hardcore in the form of the euphoric rave stabs on the title tracks, the wide-eyed Detroit melodies and UR-style yelps over garridge beats on “Twice As”, the album is also littered with vocal samples, its dancefloor approach solidified by the combination of dense beats and Martyn’s irresistible shuffle on “Masks” and “Distortions”.

There is validity to the claim that some modern day techno is too backwards-facing, but Ghost People manages to balance dubstep elements on “Popgun” and his own tribute to Vangelis on the Utopian synths of “Bauplan” while dropping the straight techno tracks like the drum building, insistent filtering of “Horror Vacui” without losing its cohesion. For the author, it represented a new challenge.

“It sounds fresh to me because I never really made techno before,” he says. “I used to dance to techno, but it is very new for me to actually make it. I have always had Detroit techno ideas, but it was very hard to fit them into a 170bpm drum and bass track,” he points out.

“Being away from the centre of thing helps me because I go to Berlin and Rotterdam, get inspired and come back home to make music”

“The album is playful and I like it a lot more than the first one; it sounds fresher and more focused,” he believes. “On the first album, I tried to give it everything I had, I tried to showcase every style I could. I feel much happier with this sound.”

Ghost People also marks the culmination of Martyn’s gradual shift towards dancefloor techno which was audible on “MiniLuv”, “Is This Insanity?” and his collaboration with Mike Slott for All City, but it is realised at a time when many producers are pursuing their droning, panning obsessions in a blinker-like fashion, and run the risk of ending up in a creative cul de sac. What does Martyn make of this criticism?

“It’s always very dangerous when there is a style of music that only influences itself,” he believes. “Once people buying dubstep started making dubstep it became a problem, and if people who are making techno are only listening to techno, it’s a problem as well.”

Martyn cites Berghain’s residents as playing a key role in popularising techno, but rather than encouraging a form of neo-purism to emerge, he believes that they have had the opposite effect and have played a positive role.

“The DJs are really refreshing and it’s their choice of music that has filled the club and not due to some kind of scene,” he feels. “I like the idea that a club, a specific location can inspire a scene, and it’s not just about pure techno. Sure, if you listen to Ben Klock’s own stuff it sounds like techno for advanced listeners, but he is very open as a DJ – he follows bass, US house, techno, he is open to other influences as well. That sort of freedom, in which you hear more in their sets in the club rather than on record, is very important. As a DJ and producer, I’ve been influenced by Berghain too. My new album is inspired by it and DJing in general.”

All of which makes the choice of label for Martyn’s most cohesive, techno-focused release something of a surprise, but the opportunity to release on Flying Lotus’s Brainfeeder label arose due to the Dutch producer’s back catalogue.

“I wish I could tell you that it was a different, more exciting story, but the reality is quite boring,” Martyn laughs. “Flying Lotus got in touch with me after I did a track called “Vancouver” . He was just setting up Brainfeeder and it was originally just meant to be a label for LA artists, but then I got invited to do two events in LA and San Francisco with Kode 9 and Hudson Mohawke. They were radically different to anything I had done before, and for once it was refreshing to see people jamming on laptops,” he laughs.

After that, Martyn and Flying Lotus stayed in touch and ended up swapping remixes, before the Dutch producer was offered the chance to release his second album for Brainfeeder. The main advantage for Martyn is clear: as he says himself, “releasing on a slightly bigger label means that you can dream bigger”.

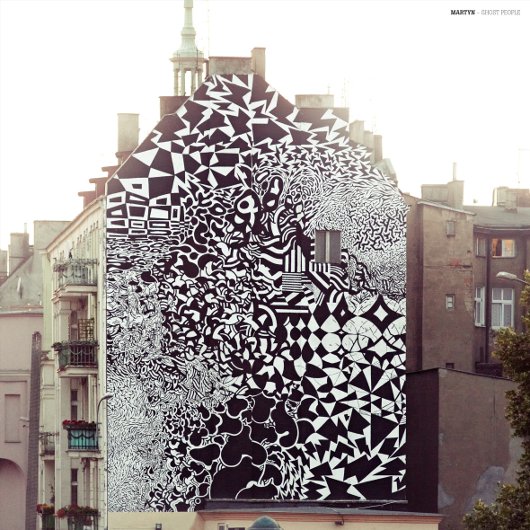

On a practical level, this means working more closely again with Erosie who designed the sleeve – “he’s been doing some great murals around European festivals and for the album tour the audience will be immersed in his art as I play live” – while on a more esoteric level it sees a continuation of the collaboration that they started when they launched 3024.

“Even though it is a different art form, a lot of the influences are the same,” Martyn believes. “Erosie has that street art influence, but it is difficult to describe what he is making now – is it pop art, surrealism or street art? I’m not sure, and I hope that people would look at my own music in the same way, that they ask, ‘what is this, is it techno’? There is a big connection between Erosie and me on a personal and artistic level – for me this partnership is really important because I couldn’t do a label with just a black sleeve.”

“The general sound I’ve always been into, not matter whether you call it techno, drum and bass or dubstep, has a lot to do with futurism and musical layers. It’s part of my musical DNA”

3024 brings us back to where Martyn started off, but it also shows where he is at. In spite of geographical differences, the label is still active, and recently put out material by Jon Convex, Julio Bashmore, Instra:mental and Addison Groove. Martyn feels that Erosie’s input is as important as the music itself, especially at a time when independent labels struggle to make ends meet.

“It’s not like the 90s or before that when you had disco DJs buying 40 records a week on behalf of the club they were playing in,” he believes. “People have very limited money to spend on records, so give them great music on both sides and beautiful artwork so they get the best value possible for 12 euros,” Martyn adds. At the same time, 3024 is not in a precarious position and he does not have to depend on it to pay the bills, which affords him the opportunity to release music by other artists.

“I have moved a little bit away from my own productions and have pushed new artists because if people know 3024 is my label, then they might also give Jon Convex a listen.”

Martyn’s feelings about digital are more ambiguous than those of many label owners, and he tries not to make a distinction between formats. “I take the retailer’s point of view about selling music – make it available in every format so people can buy it. I’ve been lucky that I’ve never had any leaks, but I also don’t think that illegal downloading is a big loss for 3024 because the people who do it are unlikely to buy my music, no matter what format it’s in,” he says.

For now, Martyn’s main concern is getting ready for the live shows with Erosie around Europe to promote the album. The tour will see him make the transition from DJ to performer, a challenge he is looking forward to. “It’ll be more improvised and I’ll be able to jam. I’ll be able to look at my music in a different way,” he opines softly, before retreating to the calm of his home studio somewhere in suburban America.

Words: Richard Brophy

Photos: Maria Eisl

Sleeve designs: Erosie