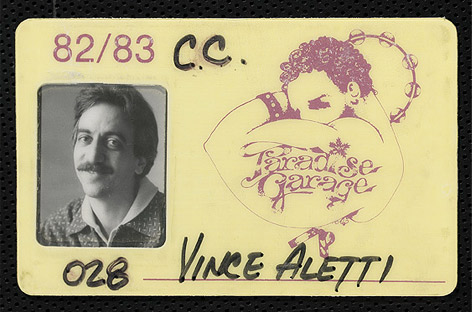

DJhistory Classic Interview: Vince Aletti

DJhistory Classic Interview: Vince Aletti

In the second part of our series of classic interviews, the DJhistory team have dug out an interview with Vince Aletti, the very first journalist to cover the emerging disco scene in 1970s New York. In this article he speaks about going to the Loft for the first time, hanging out in Larry Levan’s DJ booth and how disco went overground.

Interview by Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton in New York City, 12.10.98.

Where did you grow up?

I was born in 1945, and grew up outside Philadelphia and Fort Lauderdale in Florida. I studied literature. I went to college in 1962, just to go to college. I wanted to be a writer but I didn’t know how I was going to do it.

Had you already been a record collector?

I remember being a record collector as a kid, but not again until I went to college when I completely got into Motown. I started writing about music for the college paper. I was constantly listening to R&B, and I started writing about R&B records I heard on the radio. And that was that’s what got me my job: my friend was associated with a New York underground paper called The Rat, in ’67 or ’68.

“It was what I loved about music writing when I first got into it – that there were all these music enthusiasts. People who completely lived for music”

Did you go to Woodstock?

I went to Woodstock. Well, I left after the first day. It was too crazy. We couldn’t get through because of the traffic. The second day it rained and it was so discouraging that we left. We really were not prepared to camp out. So we hitched back to New York and I only saw part of Woodstock.

At Columbia I started writing for Fusion, Crawdaddy and a few other places. I realised that it would help me if I focused on an area that I like and that no-one else was writing about, which was black music. Rock’n’roll criticism was totally started by fans. But not very many of them really listened to black music. So every time they wanted a Jackson 5 record reviewed I did it. I was the specialist and it really helped me. I really was a Motown fanatic. So I got all the records from the record company. I was on all the lists. And I was this R&B expert.

Then I went to the Loft. I started hanging out with friends who were going out to clubs, and most of my friends had discovered the Loft. I would go their house and they would have this collection of records that I’d never heard of before. This is like First Choice, Creative Source. I was really excited.

I wrote a piece for Rolling Stone in 1973 that I think was the first piece ever written about disco. The way I sold it to them was, ‘Look here’s this music that nobody else is writing about, it’s really happening’.

The New York grapevine was so intense. A record could break in a club one night and next day everybody who cared about it would know about that record and would be running around town trying to find it, would try to find the store that had it. Just because it was a small scene and everybody knew everybody. Everybody would want to know what the new record was.

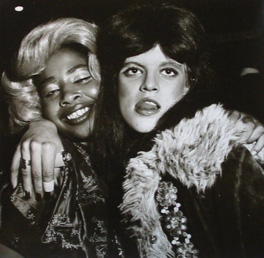

Pic: Toby Old

Were DJs protective of their records?

Not really. It wasn’t like a white label scene. At this point everybody was friendly and it didn’t feel like a scene full of rivals. They really wanted to share the music with the people in the club and tell their friends about it.

Tell us about your column at Record World

I was at Record World between ’74 and ’79 doing a weekly column. I became close to a lot of disc jockeys because I loved that they were so completely dedicated to the music. It was what I loved about music writing when I first got into it – that there were all these music enthusiasts. People who completely lived for music. Who spent all their money on music. I just loved their drive. It seemed to me that they lived for what they were doing.

What was it like going to the Loft first time?

I heard about it through this group of friends, some of whom were would-be disc jockeys. And very mixed racially, mostly gay, but not entirely. A group of friends who had become very close once we started going out. But I wasn’t used to staying up until 12 in order to go out to some place, so they had to really get me into it. But once they did it was like nothing I’ve ever done before.

It was exciting to go to a place where almost every record I heard was completely new and great. So all I wanted to do was write down all the titles. What is this? It was very exciting. And also the atmosphere was what excited me socially about clubs was that it was like going to a party. Completely mixed, racially and sexually, where there wasn’t any sense of someone being more important than anyone else. And it really felt like a lot of friends hanging out. David had a lot to do with creating that atmosphere. Everybody who worked there was very friendly. There were people putting up buffets and fruit and juice and popcorn and all kinds of stuff. It did feel like going to someone’s party, yet you were completely welcome at it.

I would go at 12, sometimes 11.30, hang out with David in the booth, because I loved hearing the music that started out the night. Some of my favourite music was David’s early records. He would play these sort of jazz, environmental things, very loose and delicate. He would make this whole atmosphere when people where coming in, before people started dancing.

“Studio 54 was the beginning of disco becoming a business of a whole other sort. I think it was destructive to have a velvet rope. It was completely against the idealism of disco and the community of disco”

What kind of records are you talking about?

These oddball things that he would discover, that were mostly like jazz-fusion records, or international world music things. Things that didn’t have any lyrics for the most part, but were just cool-out or warm-up records. It was great to see the mood getting set. Little by little, they would get more rhythmic and more and more danceable and people would start dancing. I loved seeing the whole theatre get underway. It was like being in a play before the actors had started.

You helped start the Record Pool (a pioneering set-up which distributed dance records to DJs) How did that come about?

Out of necessity basically. I really became friendly with the DJs and was really sympathetic to what they were doing. And a lot of what I heard was how difficult it was to get records. And at this point, it was clear that disc jockeys were really breaking records; they were really selling records. So they were becoming more and more important and the labels didn’t know what to do about them. Here were all these DJs coming knocking on their door saying, ‘we want a record’, and the labels didn’t know how to verify where they were working, didn’t know who they were. So it was obvious that there had to be some kind of organisation to give the disc jockeys credibility and power in the business. And also to verify who they were.

How quick were the major labels to jump on disco and exploit it?

I would say not quick at all, until ‘Rock The Boat’, ‘Rock Your Baby’, ‘Love’s Theme’ all became number one records. They all happened within weeks of each other. The disc jockeys were really proud to see their records happen, especially at the beginning. When ‘Love’s Theme’ became such a big record, they could really claim that as their own. It was so much a club record.

For a record that the label didn’t even know they had, to become huge in the clubs. It was six months after it became a number club record that it became a number one pop record.

But instead of being creative and seeing what this new music’s about, at first all they tried to do was imitate Barry White, Imitate George McCrae, Imitate Gwen McCrae. There were all these records that were just exactly like those. They didn’t happen. The record business still does. Something becomes big and they imitate it. And the imitations fail completely.

It took a while for the imitations to fall away and for people to start making creative records again. And that’s when I think disco had a second wind of really good music. I think the second wind was the Eurodisco stuff that started coming in. Like Donna Summer’s record, it gave it another punch.

When did the idea of promoting records through the clubs really take off?

Around ’74, ’75, I guess. And what was interesting was, it was the first time that a lot of gay people were working in the record business, which had always, always been a very, very traditional, straight business. I was working at CBS Records in ’69, and they’d have what they called the ‘House Hippy’, one or two people at a label who could plug them into what kids were really listening to. So there’d be some long-haired guy working at the record label who would be their hippy. When disco came, they knew that all the traditional promotion guys, who were all, typically, these straight, older, out-of-shape guys, were not going to work. Little by little, they realised they would have to bring someone in, and often they would hire somebody who was an ex-disc jockey, or someone who was working in a club.

And the guys who got hired were almost exclusively gay. And it really changed record companies. I mean, it was really interesting to me to watch this happen. As they started hiring people and changing, and having to deal with some fairly flamboyant characters.

Pic: Peter Hujar

The House homos then?

Well, Homo Promo was what they all called themselves! (laughs).

When disco ‘crashed’ were people able to hold on to their positions?

Only a few of them. They really disbanded the departments really quickly. There were a lot of records that were still happening, but nobody wanted to call them disco any more, so a lot of those departments continued as dance music departments. Historically, I think it was a matter of people being uncomfortable with the name in the end.

Was there a point where one record didn’t happen, whereas the previous one had?

No, it wasn’t quite like that.

When they blew up all those disco records at Comiskey Park, did that signify something?

I think so. Coming over on the plane, I happened to see The Last Days of Disco which I hadn’t seen. There’s footage from the Comiskey Park thing. It was just an acting out of a feeling that had always been in the air.

It was a rock DJ behind that, wasn’t it?

Right. There was always that feeling and resentment.

Was it labelled as fag music around that time?

To some extent, I mean people weren’t that brazen, or obviously homophobic about it, but certainly that was the undercurrent.

Was it distaste from the record-buying public, or distaste for this social movement?

A little bit of both. I think it was the record companies and radio just got tired of it. To some extent, the success of Saturday Night Fever was the end of it all, and also the influence of Eurodisco at a certain point. I always think that when something becomes so big and so successful the business thinks it’s got to move on. My feeling was it was very much because of radio. Radio was still very traditional. It was very straight, very rock’n’roll and most of the people there were just not interested. They didn’t care about the music, they only played it because it was a hit. And they were only too glad to see it go.

Did it feel like the end of an era; were there a lot of casualties?

Well, there already were casualties in the business because there was a huge drug-taking period. A lot of the people who didn’t die later of AIDS, overdosed. A lot of the key, early disc jockeys, overdosed during the early eighties.

What about the clubs post-disco?

It became another creative period for the disc jockeys, the same way pre-disco was, that they had to go out and look for records. They had to go out and find odd things. So there became more quirky records, more oddities. And that’s what had drawn me to it in the first place. And people made more unusual connections. It was easier to play the Clash and Loleatta Holloway. A lot of the records that came after that, the big Garage records, were more interesting than some of the records that came out at the height of disco.

“The Larry Levan legend is beyond any reason; it just sort of feeds on itself to some extent”

Labels like Prelude and West End didn’t really come into their own until the fag end of disco.

Things didn’t have to fit into a mould. They were less and less formulaic. It was what I like about disco in the first place. It had no formula. It was completely unexpected. There were all these things you just couldn’t predict. What bothered me about the label ‘disco’, especially as it became used by the business, was that it meant formula to a great extent. And so it wasn’t open to the creativity that was there in the music. When the Eurodisco sound – like Donna Summer – became the definitive disco sound, everything else around it became less and less disco and more and more freaky, in a way. It was possible for all these other records to happen, but the Eurodisco thing was like over. Except, embarrassingly enough I think, in certain gay clubs, where the only thing they played were these hi-NRG disco records.

So what about the Garage?

I never went out as much as most of my friends did. So when I went to the Garage, I’d hang out in the booth, which usually ended up being a number of Larry groupies and promotion people and other club employees. And seeing this scene of people coming to play their record, getting Larry to hear something, or leaving off an acetate.

Why is Larry Levan so revered?

The Larry legend is beyond any reason; it just sort of feeds on itself to some extent. It was mainly because Larry had the ear of Frankie Crocker at WBLS. At that point it was the radio station and he was the big disc jockey. And he was the only who was really clued into disco. And he would go to the Garage. That was the place he knew he could go and be comfortable and hear new things. So Larry became incredibly important. Beyond the fact that he was a good disc jockey and he had a great club. He had the ear of the most important radio disc jockey in the city.

All those factors made it the hot club. It was a big, it had performers – which not all clubs could afford or had the space to do – so Grace Jones would perform there, Loleatta Holloway would perform there. Everybody who had a record to push would get to perform there. One thing fed into another. It became important because of all of these factors. And it helped that Larry had a great ear, was a good mixer, and had an interesting crowd.

“The record business still does it now … something becomes big and they imitate it, and the imitations fail completely”

In terms of disco as an underground force, would you say Studio 54 was the beginning of the end?

It totally got rid of the democracy of the party. It was the beginning of disco becoming a business of a whole other sort. And, I thought, really unattractive. I would never go to a place where I had to worry about whether they would let me in or not. I think it was destructive to have a velvet rope. It was completely against the idealism of disco and the community of disco.

There’s a scene at the end of the Last Days Of Disco one of the characters has this very idealistic speech where he says disco was a whole movement. It was funny, but it was really true and people felt that. They felt disappointed that the idealistic quality of it was being trampled over, in favour of money and celebrity. As much as disco was glitzy and certainly loved celebrity culture when people came to clubs, there was never a sense of it being driven by that. It was much more driven by an underground idea of unity.

If it was idealistic, what would you say was the manifesto?

Love is the message.

Vince Aletti’s personal memoir, The Disco Files 1973-78: New York’s Underground, Week By Week is available from DJhistory.com. With reviews of every disco record worth knowing about, weekly reports from New York’s club scene, classic magazine articles and 800 contemporary club charts, this is the definitive chronicle of disco.

Main pic: Andrea Modica