Crate Of The Nation: The Digging Detectives

In the final part of his exploration of the record collecting scene, Matt Anniss examines the blossoming realm of the reissue, talking to those who go to extreme lengths to officially license rare and obscure music.

The music industry has always been addicted to repackaging old music. Nostalgia, after all, is a powerful thing. For decades, major labels have boasted “catalogue marketing” divisions, responsible for finding new ways to package old rock, pop, funk, soul, disco and jazz.

Move away from the global corporations, and you’ll find sizeable, semi-independent labels and “music groups” who have spent the last few decades Hoovering up the rights to long-dormant soul, funk, disco, house and techno labels from around the world. These vast archives allow them to make money in all sorts of different ways, from putting together themed compilations, to reissuing out-of-print albums on a multitude of formats.

In recent years, a host of smaller, independent record labels have been trying to take on the big shots. Helmed by obsessive record collectors and those with specialist stylistic knowledge, these labels exist to not only introduce listeners to overlooked music, but also put previously hard-to-find records in the hands of those who cannot afford to pay extortionate prices.

Take a look at the new release listings on record store websites week after week, and you’ll notice a spate of slick Italo-disco reissues from Dark Entries, re-discovered and repressed private press boogie gems from People’s Potential Unlimited (PPU), collections of bedroom-made ‘80s new-wave from Minimal Wave, immaculately presented Balearic curiosities from Amsterdam’s Music From Memory, and first vinyl editions of little-known African cassettes from Awesome Tapes From Africa. And that’s before you get to the brilliantly researched compilations and artist retrospectives promoted by the likes of Strut, BBE, Trunk Records, Favorite Recordings, and Californian dreamers Light In The Attic.

These days, it seems, obscurity sells; the rarer the original music, or the greater the story about how the reissue label’s crate-diggers came to find it, the more likely it is to find its way into the record collection of open-minded music buyers.

“The record buying public is a lot more knowledgeable now,” says Simon Purnell, co-founder of Leng and Spacetalk Records. “They can find things on YouTube, and tap into their favourite DJs’ record collections by listening to their mixes, and checking out their playlists. Also, labels want to push themselves by starting compilation series and doing reissues. It’s no coincidence that that the shift towards people being more interested in obscure stuff began to happen when vinyl became more popular again.”

Purnell is one of a new breed of “digging detectives” – label managers or DJs who go to extreme lengths in order to track down artists and license their music. It’s these people, and those they work closely with, who are behind the upsurge in officially licensed reissues and compilations.

“It’s hard to get across how much work goes into licensing obscure music,” Purnell says. “It’s perceived as a pretty boring part of the process, because you’re sat at a computer googling for hours on end trying to find people. When you find these people, the interesting part begins: learning about their lives, how they made the music, hearing their stories. It can sometimes take years of research and false starts to get to that point.”

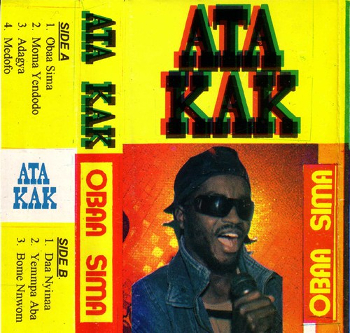

The more obscure the music, the harder it can be to find people. When Brian Shimkovitz launched the Awesome Tapes From Africa blog in 2002, the first cassette he uploaded was Ata Kak’s Oba Simaa. It took him almost a decade to find the little-known Ghanaian musician behind it, in order to license the album for rerelease.

“I had no idea who he was, and none of my friends in Ghana had ever heard of him,” Shimkovitz says. “There was no trace of him in the media, or among ex-pat Ghanaians in Canada, where he had recorded the tape. When I eventually found him, it turned out he was a really cool guy – a very unique character. He only ever made this one tape, but now we’ve managed to book him a live tour throughout the UK and Europe.”

Shimkovitz is full of these kinds of stories, but he’s not alone. A few years ago I spoke to Emotional Rescue founder Stuart Leath and he was more than happy to talk about his investigative methods.

“When I decided I wanted to reissue the Carl & Carol Jacobs record (“Robot Jam”), I had no idea how to track them down,” Leath remembers. “Somehow I found out that his band had been playing for 20 years at this fish restaurant in Florida. So I called the restaurant, and they said he’d gone back to Trinidad. Through some more work on the Internet I found a YouTube video filmed at his daughter’s hairdressing salon, and Carl was in the video. I emailed the salon, asking if I could speak to him. Eight weeks later I got a reply, asking if I would call him. Sometimes it’s easier than that, but it can also be a lot harder.”

Simon Purnell echoes Leath’s sentiments. Since founding Leng Records with Paul ‘Mudd’ Murphy, he’s worked extensively with Danny McLewin of Psychemagik, on the outfit’s acclaimed Magik series of crate-digging compilations. Along the way, he’s spent countless hours chasing up leads, only for the trail to go cold.

“There have been a few times when I’ve had to be doggedly determined to find people,” he laughs. “The Majik track on Magik Sunset Part One, “Take Me There”, was the hardest one to license, because it was a self-released, private press thing, and there was pretty much no information on the original label. The writer credited said “McCormicork”, which turned out to be an amalgamation of two people’s names, one being the producer, Ray Cork Jr. I spent ages looking for a McCormicork, who of course didn’t exist.”

The search didn’t end there, though. Purnell decided to search through American White Pages phone book listings for leads, finding a Ray Cork Jr. in Los Angeles. Predictably, it was someone unrelated to the one-time producer and arranger he was looking for. Eventually, he narrowed down the search to a small town in Arizona.

“In a moment of inspiration, I decided to email the local Tourist Information Office to see if they’d heard of a guy called Ray Cork who used to be a music producer,” he remembers. “A few days later I got a reply saying they’d forwarded me email onto him. A couple of days after that Ray emailed me, saying: ‘you’ve found me, what do you want?’.”

Purnell bursts into laughter at the memory, before recalling how the story progressed after that. “Once I started talking to him, I sent him some information about the project and offered him an advance against royalties. He replied asking for even more information, because his wife thought it was an Internet scam. You can completely understand it, though: they were both in their seventies, and there’s someone from England offering you money for a track you made 40 years ago. It probably did look a little strange.”

Cork agreed to the license request, McLewin re-edited the track, and it became one of the most popular cuts on Magik Sunset Part 1. Of course, not all license requests go this well: some artists, especially those whose short-lived music careers ended decades ago, are not so receptive.

“I’ve been turned down by artists before,” says Julien ‘Waxist’ Minarro, who has put together compilations of Caribbean disco and boogie for Favorite Recordings. “It was really complex to find one particular artist, and when I eventually tracked him down he refused to discuss anything about his music. It was like it was part of his life that he didn’t want to deal with any more. It’s frustrating, but it’s fair enough: he made the music, so the choice is his.”

Just as record collecting is a notoriously competitive business, so is the reissue industry. Stuart Leath and Brian Shimkovitz have both received online abuse from people involved in other reissue labels. “I have no ego about it,” Leath says. “If another label gets there first, fair enough. At the end of the day, it’s about the original artist and the record itself, not the specific label that reissues it.”

Just as record collecting is a notoriously competitive business, so is the reissue industry. Stuart Leath and Brian Shimkovitz have both received online abuse from people involved in other reissue labels. “I have no ego about it,” Leath says. “If another label gets there first, fair enough. At the end of the day, it’s about the original artist and the record itself, not the specific label that reissues it.”

For all the competiveness and the sheer hard work it can take to track down artists in order to license tracks or releases, all those I spoke to for this feature said it was hugely rewarding.

“There’s a story in every record,” says leading record collector and Lovevinyl co-founder Zaf Chowdry. “People move on, do different things in their lives and forget that they made some of these records. In order to reissue Martin L. Dumas’ “Attitude & Belief” on BBE, I tracked down his widow and children. They were elated that somebody wanted to put out his music again. The fact that it was unexpected probably made it more exciting for them. It’s a good thing.”

There are numerous examples of previously obscure artists whose careers have been reignited by contemporary reissues of their work. Previously little-known ambient producer Gigi Masin has become in demand following Music From Memory’s 2013 retrospective of his work, while a number of the artists championed by Awesome Tapes From Africa have returned to live performance after years away.

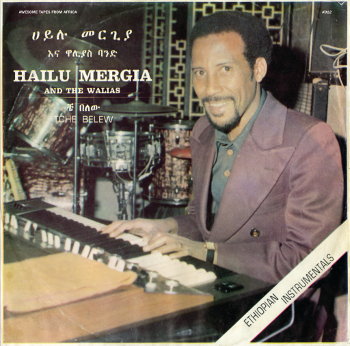

“In some cases it’s a really life-changing thing,” Brian Shimkovitz says. “Hailu Mergia from Ethiopia had been driving a taxi in Washington D.C for 30 years, and until we rereleased his album, he’d not performed for 25 years. Now he’s out there doing it again, though he still does drive his cab.”

Shimkovitz is now acting almost as a “de facto” manager for a number of the artists whose work he’s reissued, and takes great pride in helping them make money from music. “Many African countries are not linked into the music industry in the way that other countries and regions are,” he says. “Part of my mission is to get these musicians’ music in front of people who make decisions about which tracks to use on films and TV shows. I’m trying to help these artists with that, and I see us as equal colleagues. I have to work a lot on the details, and it’s a lot of work, but I think it’s worth it.”

Not all reissue labels develop relationships with the artists whose music they rerelease, but those that do make the effort can sometimes be rewarded. The first release on Danny McLewin, Simon Purnell and Paul Murphy’s Spacetalk Records was a reissue of a ridiculously obscure, private press record from a politically motivated duo called Morrison Kincannon. Once Purnell had done a deal with Norman Morrison to re-release the record, the Californian – now an estate agent in San Francisco – began sending him large amounts of unreleased music, all of which was recorded during the same period.

“I think we’re up to 60-plus tracks now,” Purnell reveals. “We asked him to send them all over so we could potentially put together an album. We’re just trying to work out which tracks to use, now. Amazingly, he still has the multi-track parts for many of these, which means we can look to do new versions, remixes, or even just get them mixed and mastered in the best possible way,” Purnell says. “It’s a good example of nurturing a relationship with an artist through mutual respect – he feels happy doing this project with us.”

The rapid expansion of the reissue scene, and particularly the “obscurist” end of the spectrum, raises another interesting question: will the reissue bubble inevitably burst sooner, rather than later?

“That’s a question I ask myself a lot,” Julien Minarro responds. “For sure, there’s a limited amount of quality material, particularly private press stuff, that was released in the ‘70s and ’80. That means there’s got to be an end to that sort of reissue activity at some point. Yet we also see new genres being explored, or re-explored, which triggers new activity around them. It’s always moving. The more I get into it, the bigger the ocean of music seems to be.”

Matt Anniss