Drvg Cvltvre – Hard Habit to Break

With the arrival of a new album, Vincent Koreman speaks to Richard Brophy and discusses how a desire to make “slower, darker music” has manifested in his prolific output as Drvg Cvltvre.

Sometimes disillusionment can be a powerful force. In Vincent Koreman’s case, he has channeled his frustrations in a positive manner. The affable Dutch producer has been playing and making music for all his adult life, but it is only now, as he reaches his mid-40s, that he is finally achieving recognition. As he waits expectantly, however, for the finished copies of his debut album as Drvg Cvltvre to arrive, he can truly say that he did it his way. Koreman’s roots lie in the new beat scene that swept through the Lowlands in the ‘80s, and like so many of his peers, he started his DJ journey in a humble environment.

“When I started DJing, I was only 16. I was playing music at the youth centre and suddenly new beat happened. We just had a strobe light and a fog machine and all our friends went nuts! At the time, this (new beat) is all were really playing,” Koreman says. “It fascinated me very much but along the way I guess I lost track of it as music and only in recent years went back to it,” he explains.

Apart from new beat, there were other key influences and events in Koreman’s life. He cites the summer of love, which also seeped from Belgium into the Netherlands, as having an impact, but he also refers to two local Dutch collectives as also playing a seminal role in his upbringing; Bunker and the Psychic Warriors Ov Gaia.

While Guy Tavares’ label and parties have been documented already on Juno Plus and elsewhere, less is known or has been written about the Warriors, who hailed from Koreman’s hometown of Tilburg. In Vincent’s mind, this local collective were ahead of others in the Netherlands.

“One of the guys from Psychic Warriors worked in a record store near me and he would hold me over loads of great records. Some of the other guys were into weird Temple of Psychic Youth rituals,” Koreman states referring to the followers of Genesis P Orridge’s Psychic TV. “They were scary, but they did the best parties at the time. They were the first people who brought over DJs like Paul Johnson and Elbee Bad and their parties were a mixture of goths, alternative types and ravers,” he recalls.

Of equal importance was the music Psychic Warriors Ov Gaia were producing. “The Psychics did some great trance records before that became a dirty word. They helped me to understand that it was OK to use four to the floor beats. Before that, I was mainly making electro beats,” he says.

Of equal importance was the music Psychic Warriors Ov Gaia were producing. “The Psychics did some great trance records before that became a dirty word. They helped me to understand that it was OK to use four to the floor beats. Before that, I was mainly making electro beats,” he says.

As Koreman’s fascination moved from just DJing into production, he decided to take a chance and send an unsolicited tape to Guy Tavares. He claims that he was merely looking for some guidance and was unprepared for the reaction.

“I think that I pretty much owe him everything,” he says of Tavares. “I was playing in a band at the time and knew him through a mutual friend. I sent him a tape to ask him how to put out a record – I wasn’t trying to get signed – and he called me the next day and said that he wanted to sign me to Bunker. He scared the shit out of me because he called me an hour later and said ‘I want to release this right now’. It was the first time that anyone had taken an interest in the music that I was making,” Koreman adds.

That record, Dr Rhythm’s Scania Trax appeared on Bunker in 1997. It was recorded under that alias, Vincent explains, at Tavares’ suggestion, because it coincided with a high volume of music that Koreman was also releasing as Ra-X on the Belgian label Kk.

“They had signed Unit Moebius (I-F’s band) and Psychic Warriors Ov Gaia but the relationship got a bit strange because I saw releases coming out under my name that I wasn’t into, so in the end, I told them to get lost,” Koreman says. He kept recording as Ra-X but by this stage, techno generally in the Lowlands was veering into a monotonous, high-octane jackhammer cul-de-sac. The end of that project was in sight.

“The last Ra-X records were 140-145 bpm nosebleed techno. I got really bored of that because I was playing to 5,000 people off their heads in warehouses in France and Belgium,” he recalls.

Frustrated with the prevalence of gabba and harder, brainless sounds, he turned his back on electronic music and became a paid touring member of band called The Travoltas. Signed to the indie label Roadrunner, they underwent a grueling touring schedule. It was the final straw for Koreman.

“I was touring constantly and it was a lot of hard work. I got so sick of the music industry, I quit for a while,” he admits.

When he eventually started to make music again, he was making “really harsh noise and only releasing it only on CD-Rs. It was like I was a punk again but using electronic music as a way of expressing how I felt”. However, from this period disillusionment Koreman emerged stronger. He had learned a number of hard lessons along the way, but his musical knowledge ensured he enjoyed a fresh start. In particular, he was guided by his early experiences with new beat and acid house.

When he eventually started to make music again, he was making “really harsh noise and only releasing it only on CD-Rs. It was like I was a punk again but using electronic music as a way of expressing how I felt”. However, from this period disillusionment Koreman emerged stronger. He had learned a number of hard lessons along the way, but his musical knowledge ensured he enjoyed a fresh start. In particular, he was guided by his early experiences with new beat and acid house.

“When I went back to producing in 2008, I wanted to make slower, darker music. With lower BPMs, you can have much more details and textures in your music,” he believes. “I also didn’t want to go back to the ‘drug culture’. I thought that spelling it right was too much like an endorsement, but I had already made some tracks under that name and I didn’t want to change it,” he says of his current project, which is pronounced the way it is meant to be spelt.

“People misinterpreted my name. Everywhere I go, people ask me if I want drugs, and I answer ‘no, I’m just here to play records!’”

Reinvigorated by this new name, if not by some of the misunderstandings it caused, Koreman set about releasing music that coalesced acid, techno and formative sounds such as new beat and EBM. From 2012 onwards, this led to a series of albums and EPs on his Snug Life label, while appearances on Viewlexx and the debut release for Pinkman helped to raise the profile of the Drvg Cvltvre project.

In the same way that he praises Tavares for giving him one of his first releases, Koreman is unequivocal about why the Viewlexx release was a pivotal one. “I-F and I have been in touch for years. He gives me feedback on my tracks, maybe just a few words. The EP he released, he liked all the tracks and decided straight away to release all of the ones I gave him. I am very lucky to have this connection,” he says.

Vincent also says that I-F and Tavares are also partly responsible for the environment which has given rise to a high proliferation of Dutch labels, many of which he has released on.

“There is a lot of music being made here that is of a very high quality and with Pinkman, Marsman works very hard with that label and it is going to pay off, but there was also a lot of groundwork done by I-F and Guy. Plus there is also a resurgence of vinyl, but a lot of it was the hard work was done by the old school guys,” he believes.

This goes some way to explaining why he has put out music on so many different labels – mainly Dutch ones – but Vincent says that there are other reasons.

“A lot of labels find me easy to communicate with and if I get asked to release a track I usually say yes,” Koreman says. “This means that a lot of labels start off with one of my records and then they get successful and attract bigger artists, and off they go. What usually happens is that I get a 12” from a label about half a year after I sent them tracks and then I never hear from them again. It’s OK, I have come to terms with it!” Koreman jokes the same thing happens to Legowelt too, adding stoically, “I guess that’s just the reality of releasing music in 2016.”

This may the case, but it is more likely to do with the fact that Koreman’s music is awkward. For starters, it’s slower than gloom-mongering big room fodder, prowling along under 120bpm for the most part, and draws on sources outside of the creative techno whirlpool.

“The last Ra-X records were 140-145 bpm nosebleed techno. I got really bored of that because I was playing to 5,000 people off their heads in warehouses in France and Belgium”

Koreman explains that he has been propositioned to change how he makes music for his own commercial benefit. “I have had these conversations with booking agents who say, ‘you know, if you could just speed up your tracks a bit, by a few BPMs, you could play eight gigs a month and earn 1,500 euro for each gig, and give up your day job.’”

“That all sounds fine,” Koreman adds, “but when I turn on my machines, I find it physically impossible to do that. I am much more comfortable nowadays flying in and from a gig and not having a touring lifestyle.” Koreman has a day job that he loves, “I am director of the Incubate Festival in Tilburg, where I live. It’s a week-long festival and we have about 380 acts playing.”

He feels there is only so much you can control in your life, “and one thing I can control is the music I make and share with people. I want people to understand and enjoy it,” he says. In any event, he believes that after 20-odd-years, it is time that techno’s mainstream sits up and listens to ‘its darker side’. To illustrate his point, he refers to UK label Downwards.

“It has been going for over 20 years now and Surgeon has never been more popular than now – a lot of the guys who have been around for years are getting more recognition,” he feels. Despite this remark, Koreman does not harbour too many sentimental feelings for ‘the good old days’. He says that New York Haunted, the label he curates, is mainly intended as a platform for new, break through artists – in the same way that Bunker gave him a helping hand – and he despairs of modern artists trying to make their music sound like it was made 20 years ago.

“The most retweeted thing I ever wrote on Twitter was ‘your dark techno is not the sound of the future, it’s the sound of 1997’. I hear a lot of tracks that are degenerated digitally to make it sound authentic, but they are not fooling me,” Koreman says, warming to the topic. “You know, it’s lame and lazy to go back to the same pond all the time. Your advantage nowadays as a producer is that you have the ability to go back to everything and be more innovative. Use these sources as a starting point and then blow me away,” he states.

Given his background and long history with electronic music, what does Koreman make of the almost weekly reissuing of obscure releases from the ‘70s and ‘80s? His response is revealing: “Sure, it’s nice to have a new vinyl pressing of music that might have been hard to find, but it has become a little bit of a hype and I’d rather focus on the present. There are still people nowadays who make a lot of really interesting music and we should be focusing on them.”

Initially, Koreman’s own prolific work rate led him to set up New York Haunted, so he could release digital versions of his tracks. “If you are putting out vinyl, it always takes a long time. I send you some tracks and before you know it, it’s a year later. If it’s something that I want communicate quickly, then it’s great to do it that way,” he notes.

He also explains that the other reason for setting up the label was due to the fact that people were adding free tracks he gave out online to Discogs. “It really bummed me out when I saw these free tracks listed as ‘not on label’ on the site. It’s not cool,” Koreman says.

From relatively humble beginnings, New York Haunted has moved into the vinyl sphere and the next few releases comprise a split 12” between Drvg Cvltvre, Terrence Dixon, Hieroglyphic Being and Pete Swanson, followed by a solo EP from Nordic ambient godhead Biosphere.

“These are some of my favourite artists,” he explains. “Biosphere recorded the release when he was in the Netherlands recently on a visit. Terrence is a great guy, straight up, no bullshit. Jamal’s music is very much a reflection of who he is as a person – you can hear he has been through a lot and has lived an unusual life. You can probably hear that I am a reasonably well off white guy in my 40s, so I have absolutely no street cred!” Koreman is keen to stress that New York Haunted will continue to support new talent and cites German duo Fallbeil as one of the acts release an EP on the label soon.

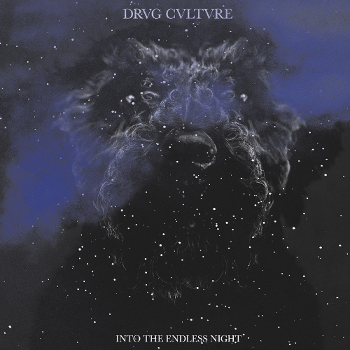

The other main activity that has been keeping Koreman busy is recording and putting the finishing touches to his debut Drvg Cvltvre album. It’s called Into the Endless Night and is to be released imminently on Pinkman. The Dutch producer says that he has put a lot of hard work into it. Beginning with the booming bass and murky vocals of “Where Embers Die,” the album takes inspiration from Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s 1932 nihilistic but brutally funny novel Journey to the End of the Night.

From this foreboding start onwards, Koreman steers the album through a variety of directions, from the distended sheet metal “Shock Corridor” and towards the somewhat more accessible electronic disco throb of “Charge of the Haploids” before disappearing down the rabbit hole with the foreboding screeches and ominous rhythms of “Brakes Are Death”, only to -re-emerge with the innocent sounding melodic hooks on the title track. Each track plays out like its own dedicated little mini-drama, albeit ones that are grounded in the grimy, grungy Drvg Cvltvre sound.

“It’s all about death. All my songs are,” he says about the album. “It’s tied to life, and death is a part of life really. There aren’t too many love songs in there. Normally I work very fast, but this time I wanted to have a theme throughout the album. You can hear it’s my work, but it’s like a book full of short stories. I am trying to reach something bigger than normal. I wanted to reach a higher level, I want to transcend music and be like when Sun Ra is jamming with his band,” Koreman says, showing his ambition for Drvg Cvltvre.

“It’s all about death. All my songs are,” he says about the album. “It’s tied to life, and death is a part of life really. There aren’t too many love songs in there. Normally I work very fast, but this time I wanted to have a theme throughout the album. You can hear it’s my work, but it’s like a book full of short stories. I am trying to reach something bigger than normal. I wanted to reach a higher level, I want to transcend music and be like when Sun Ra is jamming with his band,” Koreman says, showing his ambition for Drvg Cvltvre.

While the title track hints at melodies, Koreman quickly veers into the brutally awkward “There Were Rumours”, its grimy acid tethered by ear-splitting percussion and nauseating vocal samples and “Jericho Flats”, a muscular, oppressive take on electro, the drums hammering like a rivet gun as synths conjure up an appalling vista.

“There are tracks that might work in a Hieroglyphic Being DJ set. I don’t know him very well. He produces a lot of music, like me, but he has a very different approach,” he says by way of explanation.

Despite his refusal to raise the project’s BPMs or make anything approaching streamlined techno, the Drvg Cvltvre project is receiving increased bookings.

“I like doing DJ sets because it gives me a chance to play stuff from 25-30 years ago, like old Front 242 stuff. What you have to remember is that some of these acts had real messages for their fans. It doesn’t seem to work that way now, but a lot of the people at the clubs haven’t heard that kind of music before and it blows their mind,” he explains.

After twenty years at the fringes, Drvg Cvltvre could prove to be the hardest habit for Koreman to break.

Interview by Richard Brophy

Vincent Koreman profile pictures courtesy of Verena Blok

Into the Endless Night is out this week on Pinkman