Breadwoman – Speaking in Tongues

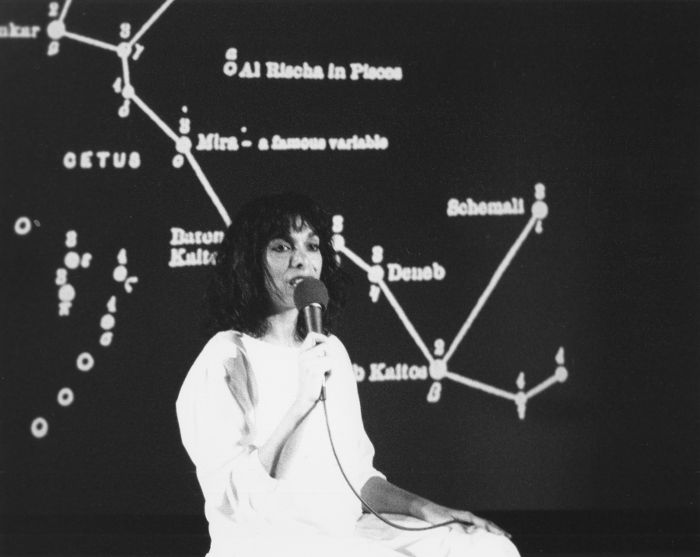

To celebrate the arrival of her reissued album on RVNG, Anna Homler details the three decade-old story behind Breadwoman in this delightful interview with Brendan Arnott.

Things have a way of coming full circle. For example, Anna Homler was wearing bread on her face thirty years before it was cool. On the morning I contact the Los Angeles-based performance artist and singer, the internet is abuzz with a new trend called ‘bread facing’, where an anonymous woman with 47,000 Instagram followers mashes her visage into various types of gluten-filled loaves. When I ask if Homler’s aware of the trend, she laughs. “I saw that and identified! I said ‘Oh my God, she’s feeling the need to wear bread too!'”

As an avid believer of philosopher Carl Jung and his work on archetypes and the collective unconscious, Homler’s not surprised that someone else grasped at an idea she first pioneered in 1985. Homler’s own work as Breadwoman, a mythological storyteller so old she turned into bread, is also experiencing somewhat of a resurgence, with her 1985 cassette Breadwoman newly re-issued in expanded format on RVNG Intl. In it, Homler’s special brand of speaking in tongues sounds as enthralling, complex and mystical as it did three decades ago, with her lyrical fragments mixed and engineered by Steve Moshier. Plucking syllables from the far reaches of the universe, Homler’s voice is celebratory and mournful in turn; holding ecstatic communion with history, time, space and place.

As I speak to her from her Los Angeles home, she’s sipping coffee and packing for an upcoming Berlin showcase, bubbling with the easy-going positivity and energy of an elementary school teacher. With a 30 year gap since the concept was dreamed up, I’m curious whether Breadwoman ever faded into obscurity for Homler during that time.

“I think it was a stage, or is a stage in my evolution as a vocalist,” she responds, “that character, she’s how I started to sing, but even after I took the bread-head off, that’s what I’ve been doing, and the language that came to me as Breadwoman.” In that sense, Breadwoman has become a part of Homler, so much so she rarely sings in English, admitting to having only three English songs in her whole catalogue. “For the last few years, I’ve worked mostly with other improvisers,” she adds, “so I make different choices. Now my work is more about the sound, about listening and being part of a collective ensemble.”

As Homler gears up for her trip to Berlin, she’ll be playing alongside Steven Warwick, better known as Heatsick, whose body-centric psychedelic tunes operate on the fringe of dance music. RVNG boss Matt Werth was responsible for the pairing, and he told me, “knowing Steven’s background in creating minimal, primitive soundscapes and rhythms alongside his fascination with Los Angeles’ undercurrent of mysticism, the pairing was calling out from some other ether.”

As Homler gears up for her trip to Berlin, she’ll be playing alongside Steven Warwick, better known as Heatsick, whose body-centric psychedelic tunes operate on the fringe of dance music. RVNG boss Matt Werth was responsible for the pairing, and he told me, “knowing Steven’s background in creating minimal, primitive soundscapes and rhythms alongside his fascination with Los Angeles’ undercurrent of mysticism, the pairing was calling out from some other ether.”

At the time of the publication, Homler and Warwick are improvising in Berlin together ahead of their show at Berlin’s CTM festival. There are a million ways to improvise, from Anthony Braxton’s elaborate synaesthetic cliff notes, to Golden Teacher’s ‘meltdown-chic’ spontaneity, but I’m curious how Homler approaches it.

“I was joking with Steven that I’m like a sonic mail order bride, coming into this scenario,” she chuckles, before stating regular email and Skype correspondence happened beforehand to try and clarify some points of interest. But in the end, Homler doesn’t seem prone to over thinking. “As long as we have lines of communication and we listen to each other, it usually works,” she says. Steven Warwick agrees, telling me by email that playing alongside Homler has felt “intuitive” and the duo have been creating nonstop.

Breadwoman’s work has found a home in many spaces: punk events, gallery culture, outsider jazz communities and drag shows, I’m curious if her work alongside Warwick’s will mark a new-found immersion in the world of club music. As it turns out, I hadn’t done my homework. “Actually, I used to be in, well, still am in, a project that’s just kind of sleeping at the moment called The Voices of Kwahn, out of England,” Homler tells me. “We had five releases, and the early ones were very much dance and club music. We had a hit called “Ya Yae Ya Yo Yo Yo” that made it on a Cafe Del Mar compilation, that was kinda our big track.”

I quickly google it, and my jaw drops. Homler’s voice remains haunting, poetic and ineffable, but with gigantic, cheesy Ibiza synth lines crashing against her vocals like waves on a beach. “It’s not my first time around the dance music rodeo,” Homler warmly concedes, a reminder her prolific nature has spanned multiple genres.

It’s easy to miss some pieces in Anna Homler’s career, if for no other reason than there are just so many. An active performance artist before she took up the loaf, Homler’s pre-Breadwoman projects included such as ideas as setting up shop at a book store and sleeping there throughout the day, and another where Homler tells me, “I turned my Cadillac into an underwater shrine, and gave people whale rides.” I don’t dare to ask her to elaborate on this concept.

The common thread between these works? “My early performances were about the intersection of reality, intersections through different dimensions” she states, animated. “I saw them as poetic eruptions, or disruptions, into daily life. My early performances were storytelling in a way, and so from that, Breadwoman evolved very slowly and organically.” Homler happily admits she just kinda followed the trail, “Breadwoman didn’t emerge fully blown, she evolved and it was like putting puzzle pieces together.”

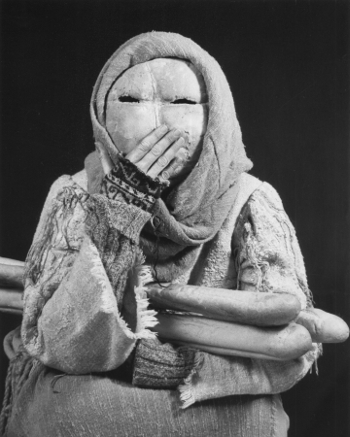

If the title of Homler’s Breadwoman doesn’t catch your attention, the accompanying photos certainly will. With a lumpy mass of gluten where a face should be, colourful robes, and baguettes carried like magic wands, Breadwoman’s physical persona straddles the line between comforting matriarch and a shadow-lurking mutant; both comforting and repulsive, homely and other dimensional. It instils a morbid curiosity in the viewer, what Heatsick describes as “somewhat haunting, yet delicate”. You’re a bit scared, but you also want to break off a piece for a taste.

How does Homler conceive of the Breadwoman image? “In the beginning, she began as more a type of Grandmother, or peasant,” she tells me, “but she does have an element of the Elephant Man, and the feeling of the outsider or the homeless person. She’s a lot of contradictions at once.”

Whether you read Breadwoman as a protective ancestor, or demon woman lurking behind the dumpster in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive is up to you. But Homler has always been crystal clear the purpose of this project revolves around the idea of musical communication. Exactly what kind of communication is she hoping to achieve?

“Resonance with the listener, I think,” she explains. “My hope is the person who’s listening will connect with that language – the people who connect with those sounds, really connect to it.” She pauses. “I don’t really have a message… I’m Breadwoman! If there is a message, maybe it’s wholeness. Wholeness embraces the darkness, it embraces that ambiguity, it embraces the grandmother and the elephant man, the familiar and the strange. Just to be able to be in that ambiguous space, that’s wholeness. It’s not perfection, but it contains everything.”

Inventing a language without ascribing some kind of meaning to it seems like a pretty difficult task, so I ask Homler whether the made up words she sings have any meaning, or whether it’s all about the spoken sound, the sonic textures of the words themselves. “There are a lot of threads here,” she responds with a laugh. “When I started to sing, I could feel like ‘a song coming on’ – it was this intuitive, approaching thing. I’d get my cassette player and record whatever the melodic phrase was. Maybe it’d be triggered by an outside sound, or it’d just emerge on its own. I was kinda like a hen laying eggs, a song would come.”

Homler divided her work into different camps. The recordings which fit into more of a traditional pop framework were made alongside Ethan James, famous for producing seminal ‘80s acts like Black Flag and The Bangles. Homler describes these offerings as “more like the songs you’d hear if you were on a bus in a foreign country” – pop music with an outsider twist. The looser structured, experimental work she describes as, “more like landscapes,” were recorded alongside Steve Moshier, and came to form the basis of the original Breadwoman cassette.

Homler divided her work into different camps. The recordings which fit into more of a traditional pop framework were made alongside Ethan James, famous for producing seminal ‘80s acts like Black Flag and The Bangles. Homler describes these offerings as “more like the songs you’d hear if you were on a bus in a foreign country” – pop music with an outsider twist. The looser structured, experimental work she describes as, “more like landscapes,” were recorded alongside Steve Moshier, and came to form the basis of the original Breadwoman cassette.

“For songs recorded with Ethan, sometimes I’d see images that went with them, but it was never a word-for-word translation,” Homler says. Certain songs represent generalised images, such as “a song for fallen warriors,” or a striking image that gripped her of women dancing in a white walled city somewhere in the desert. “A lot of my early songs were laments and lullabies, songs for lost worlds. But I couldn’t tell you where this world was,” she admits.

The sense of fluidity in Homler’s music operates in stark contrast to singers like her and others such as Marie Boine, the native Norwegian musician whose traditional Sami Joik singing of her culture is loaded with personal meaning and history. Meanwhile, Homler sidesteps particular cultures and attitudes, pulling from a more universal framework, digging around the edges of something that’s been embedded in the world for a long time. Homler feels connected to her own rituals and ceremony, but sees it as personalised to her own life.

“I love rituals and ceremonies in my own life, but they can be non-traditional,” she tells me. “I don’t like codified, structural rituals, but I do love knowing what the symbolic meaning that I ascribe to. Sometimes my words come out in Serbo-Croatian, Japanese or Mandinka. I think that’s the universal quality of language.”

But the Breadwoman project remains most fascinating when it doesn’t even try to approach any existing genre, culture or language, and exists as a rhythmic and melodic stream of conscious creativity. Before Homler finishes packing her bags, I ask her whether her relationship with Breadwoman has created more questions or answers for her.

Holmder pauses, “I…. don’t know,” she says chewing over the words before letting out a warm laugh. “At this point, I’m just enjoying being outside of her, getting the opportunity to appreciate her from another perspective than the inside.” I’m reminded of one of the quotes on the liner notes to Breadwoman & Other Tales: “Bread is the twin of flesh. The one becomes the other. And after a time. Turns back again”. Things have a way of coming full circle.

Interview by Brendan Arnott

Breadwoman & Other Tales by Anna Homler and Steve Moshier is out now on RVNG

RVNG Intl on Juno