Stefan Schwander – New Roots Muziek

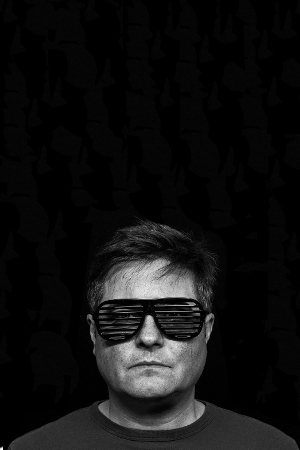

The German artist talks Harmonious Thelonious, The Durian Brothers, non-standard rhythms and Düsseldorf’s music scene with Oli Warwick.

There seems to be a healthy stream of hand-played percussion and ethnic sound sources creeping into electronic music at present. From tapping into the traditions of North Africa to instruments of the Far East, Western producers are seemingly increasingly enchanted by sounds and structures that exist beyond the metal and plastic confines of machines. This is not necessarily anything new; look back to the likes of Muslimgauze, or further still to Holger Czukay and beyond, and there has always been an allure in the exotic tones of distant cultures, but the issue does come laden with questions about cultural appropriation and respectful treatment of materials which in some cases have important spiritual or ritual significance.

Context is of course a powerful thing, and in the case of the bubbling broth of artists and labels that orbit around Dusseldorf’s infamous Salon Des Amateurs, there seems to be an innate respect and understanding of non-standard rhythms, worldly percussion and other such practices that feel a long way from central Germany. The fact is these artists seem in harmony with the sounds they are exploring, following a lineage that was arguably started by Czukay et al at the dawn of the Kosmische movement.

While artists such as Jan ‘Wolf Müller’ Schulte and Florian ‘Don’t DJ’ Meyer are starting to turn heads now, Stefan Schwander has been a fixture of the Düsseldorf music scene since before the Salon was even open. In that time he has lived many different lives from stripped down house and dub to playful electro, depending on which alias you tap into. His current and most productive project however is Harmonious Thelonious – a venture stoutly declared as: “focusing on rough and dense beats and textures inspired by American minimalist music and African rhythm patterns.”

If ever clarification was needed on the influence of Steve Reich, Terry Riley, and Philip Glass et al. on Schwander’s music, one need only look to his recent outing on debut Schleißen release from Emotional Response where two long form pieces reveled in cascading patterns of chiming melodies arranged with that distinctive non-linear approach that was pioneered in the middle of the twentieth century. It is in support of that very release that Schwander made his way to London on an unseasonably warm April evening, appearing at a Schleißen showcase at Café Oto also featuring Colin Potter, Alessio Natalizia and Guido Zen collaborating live, and a warm up performance from Northern Irish artist Sad City.

If ever clarification was needed on the influence of Steve Reich, Terry Riley, and Philip Glass et al. on Schwander’s music, one need only look to his recent outing on debut Schleißen release from Emotional Response where two long form pieces reveled in cascading patterns of chiming melodies arranged with that distinctive non-linear approach that was pioneered in the middle of the twentieth century. It is in support of that very release that Schwander made his way to London on an unseasonably warm April evening, appearing at a Schleißen showcase at Café Oto also featuring Colin Potter, Alessio Natalizia and Guido Zen collaborating live, and a warm up performance from Northern Irish artist Sad City.

As I arrive at Oto, Schwander is sound checking with a set up that seems positively diminutive compared to the hulking rig of synths, effects racks and mixers that Potter, Natalizia and Zen have brought with them. On a little table in front of the headliners, he hunches over what looks like a ‘90s PDA but is later revealed to be a Roland PMA-5, a miniscule sequencer controlled by stylus with limited capabilities but just enough scope for triggering the interlocking patterns that Schwander favours. Alongside this is a Biscuit, a cult sequencer and effects box (funnily enough made by a manufacturer called Oto) with a lot of power for a device that looks a lot like a toy. Either way, it’s a compact rig that prizes functionality over stage presence, perhaps reflecting the attitude of an artist who has been in the game long enough to see the benefit in streamlining his road baggage as much as possible.

Following the sound check, Schwander and I join the other artists in a nearby Turkish restaurant and attempt to conduct an interview amidst the clamour of a busy barbeque grill, zig-zagging food orders and clinking crockery. In hindsight, it’s the kind of heavy, dense atmosphere that can be felt at times on the most recent Harmonious Thelonious album, Santos. It’s the third studio album for Schwander’s primary creative focus, appearing on nearby Cologne-based label Italic who have supported many of Schwander’s different projects over the years. While the concept has remained intact throughout, the sound of Harmonious Thelonious has steadily changed from release to release, this time incorporating external musicians where once Schwander insisted on working solely with his own sequenced drum machines and synthesisers.

“It’s more or less the first time that I work with guests on a Harmonious record,” Schwander explains as we wait for our kofte and meze dishes to arrive. “There are Moroccan flutes, congas and instruments which I barely can imitate, which bring a new vibe or tune.”

Some of the external musical elements that appear on Santos are played by a Palestinian Berlin resident named Ghazi Barakat, who Schwander happened to catch playing live and then approached about contributing to the album. One of the record’s highlights, the towering mid-tempo “Mountains”, is embellished by flurries of frantic flute, while the opening strains of “Sans Ecole” features the instrument even more explicitly. Elsewhere the Makuta drum duties were handled by Stefan Suhr and the Turkish tambur was played by Calexico’s Volker Zander.

“You know my interests change a little and this was really more influenced by North African music than anything else,” Schwander reveals about his motivations on Santos, “and I wanted to make a real LP with eight tracks that flowed one to another. The new record is not so wild with drumming, but it’s a little bit deeper, maybe, and the first time I tried a different tempo. You have some tracks which are only 105 beats per minute.”

“You know my interests change a little and this was really more influenced by North African music than anything else,” Schwander reveals about his motivations on Santos, “and I wanted to make a real LP with eight tracks that flowed one to another. The new record is not so wild with drumming, but it’s a little bit deeper, maybe, and the first time I tried a different tempo. You have some tracks which are only 105 beats per minute.”

Although he may consider the album calmer in places, there are still moments of intensity, if not aggression. “Industrielle Muziek” lives up to its title with a mean-tempered riff and forthright rhythm section, while “Rendezvous Of The Dead” pile-drives a powerful salvo of arpeggios. It may not be loud or heavy in the traditional sense, but Schwander still has the capacity to hit hard, and that was certainly apparent on earlier Harmonious Thelonious releases such as the On Stages EP on Diskant. Equally though, there are plenty of moments of sweetness within Santos as well.

“For me Santos is more or less one theme, but I also like to have some tracks which are a little bit more melodious or a little bit different,” he reveals. “An album is good when there are lots of different points. The third track, “Late Lord Hope”, was a bit of a change because for me it’s got something to do with almost, calypso. Fake calypso I call it.”

The track in question perhaps displays more of the typical hallmarks of a Harmonious Thelonious production, marked out by bright melodic lines that fall in precise but subtly off-kilter formations that challenge the 4/4 norm. It’s a practice that reaches right back to the first HT releases, where sampling was completely out of the question.

“No samples is my way of working,” Schwander explains. “I don’t have a sampler. I’m working with a sequencer where I have to program every note, but I’m interested in the structures of music and so this way is good for learning about that as well.”

The structures Schwander refers to of course nod back to the aforementioned sources of inspiration, the American minimalists and African music. Having spent years producing more typically Western forms of electronic music, he found himself drawn to interweaving melodies, which is a facet that joins the two distinct inspirations together. On his first HT record, the purpose was to just use organ and piano sounds so as to make it difficult to discern which sounds were coming from where.

“My main interest was to get into a sort of trance,” Schwander explains of his intentions with this new direction. “The other interest is to be danceable, and so it was logical to get more and more rhythmical. Along the way I heard a lot of African music, and this is all about drums.”

Another aspect of African music that has been significant in defining the sound of Harmonious Thelonious is resonant noise. Although he never uses them in his own recordings, Schwander has been collecting African instruments for some time and through this process discovered the emphasis placed on added noise besides the primary harmonics of any note played.

“In the African records I buy there are always overtones,” he says. “Even instruments like these thumb pianos from Zimbabwe. They have tongues that you play, but they also nail bottle caps to the wood that only make noise, which is important for the music.”

Indeed the emergent noise in Schwander’s music became part of the appeal for listeners, no more apparent than in the wild frequencies of tracks such as 2010’s “Mokambo”. “I was surprised that people in Berlin and people in London liked it when I did the more harsh things that came up with the first Diskant record On Stages,” he explains. “There was lots of drumming and an almost punk attitude.”

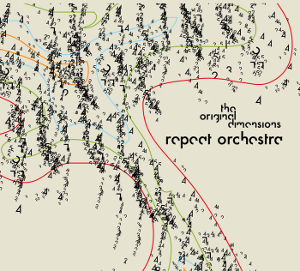

The difference in the sound of Harmonious Thelonious compared to Schwander’s earlier work was noticeable. On projects such as Repeat Orchestra and Antonelli Electr., a sleek, refined finish characterised the delicate electronics he was conjuring up from his studio. The former emerged almost exclusively on Andy Vaz’s now-defunct A Touch Of Class label, which also housed releases from Further Details, Lerosa and Akufen under his Anna Kaufen alias. The stripped back deep house sound certainly tipped its hat to the minimal scene that was booming at the time, but it had a greater emphasis on melody and warmth compared to the ‘clicks n’ cuts’ approach that was popular in the early to mid-‘00s.

“Repeat Orchestra was my favourite project back in the day,” Schwander tells. “I always think that I was doing that stuff at the wrong time. No one cared about deep house music then and now you hear it on every corner and club.”

Despite being released on a relatively obscure label more than ten years ago, the second Repeat Orchestra album The Original Dimensions received no less than two reissues. The first came from A Touch Of Class, which reanimated briefly in 2012 to release the album in a handmade wood cut sleeve, while the second was a tape issue by Cologne label Modularfield in 2014. “I’m happy that (Repeat Orchestra) is sort of timeless, especially my record for Real Soon and the first two or three records for A Touch Of Class,” he meekly considers. “The re-releases were in very limited editions though, no big thing!”

Even if Repeat Orchestra has had a lasting impact, Schwander’s work as Antonelli Electr. still represents his largest body of work. From 1997 until 2009 no less than six albums and twenty five singles appeared on labels including Kalk Pets, Level and Minuendo, with the vast majority released through Italic. Touching on melodic, emotive electro and techno, the clearly defined production and linear arrangements are a far cry from the work he does now. By Schwander’s own admission there are still tracks in that vein emerging from his studio, although he feels unsure of how he might approach issuing this new music.

Even if Repeat Orchestra has had a lasting impact, Schwander’s work as Antonelli Electr. still represents his largest body of work. From 1997 until 2009 no less than six albums and twenty five singles appeared on labels including Kalk Pets, Level and Minuendo, with the vast majority released through Italic. Touching on melodic, emotive electro and techno, the clearly defined production and linear arrangements are a far cry from the work he does now. By Schwander’s own admission there are still tracks in that vein emerging from his studio, although he feels unsure of how he might approach issuing this new music.

“I don’t know if maybe I’m inventing a name for the new stuff,” he ponders, “but at the moment it’s Harmonious, and I’ve got the most ideas for that project. It’s flowing the easiest way.”

As we work our way through a variety of dishes, interruptions and questions, three men come through the door and Schwander’s face lights up. Asking to pause the recorder, he introduces me to Radovan Scasascia and Laurent Benner, old friends of his who used to run the Dreck label. Scasascia also released music as Secondo and AM/PM, scoring an album on Soul Jazz amongst a string of well-received singles. Furthermore, as well as releasing the Antonelli Boogie EP in 2007, the London-based Dreck also gave Harmonious Thelonious its first outing with the Just Drifting 12” the following year. In Schwander’s back catalogue you can draw a line between his prior projects ceasing and Harmonious Thelonious beginning.

At that time, the crystalline tones of his previous work still permeated the sound of Just Drifting, but the leap towards cyclical, interwoven melodic phrases stood out as something entirely new, not to mention unique. When you listen to a track such as “Beiläufige Muziek” the angle of approach carries through to his present output, even if some of the stylistic traits have changed.

“I always think that I was doing that stuff at the wrong time. No one cared about deep house music then and now you hear it on every corner and club.”

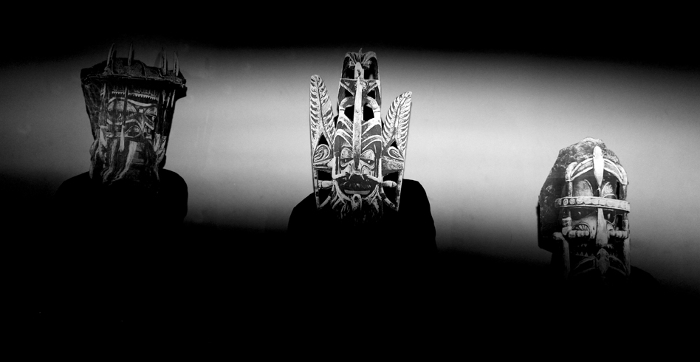

As Schwander hinted previously, it did seem as though the sonics of the project underwent an overhaul once he released the On Stages EP. It was the second 12” on Diskant, the label he set up with fellow Düsseldorf resident Florian Meyer. Meyer is best known presently as Don’t DJ, a regular fixture at Salon Des Amateurs and also one third of The Durian Brothers along with Schwander. A true product of the iconic club, the group also counts Marc Matter amongst its ranks, with Schwander controlling a sequencer while the other two work on prepared turntables and effects units to create cyclical textures that feed into a ranging, tribal sound rich with transcendental qualities.

“The Durian Brothers were born in the Salon Des Amateurs surroundings,” Schwander explains. “I was asking Marc and Flo to do a remix for Harmonious and we ended up jamming together and found out that we really can do something new when we mix our experiences.”

Matter and Meyer had already been working together for many years as part of Institut Für Feinmotorik (which translates roughly as ‘institute for precision motoricity’), with releases reaching back to 1997. The concept of record-less turntables has always been the grounding principle of the project, employing other objects such as rubber bands and toothbrushes to generate the signals they then manipulate through their effects chain. This approach carries through to The Durian Brothers, anchored by Schwander’s sequenced patterns.

“We work fast and improvised when we three are together,” Schwander states, “and I’m preparing some sequences before, to which they play their instrument, the turntable. It’s growing and growing and we have to improve ourselves when it comes to how we can record that stuff in an almost live situation, and find different methods to write tracks.”

The Durian Brothers is a fine example of the creativity that currently bubbles up from Salon Des Amateurs and Düsseldorf in general, and as a resident of many years it seems as though Schwander is something of an elder amongst the city’s blossoming scene. While he happily celebrates the infamous, fearless musical policy of the club as a great testing ground for new material, he also points to the fact that there is actually very little going on nightlife wise in Düsseldorf as one of the best motives for focusing on creative ventures instead of relentless socialising. Whatever the case, the hub of SDA and its unconventional DJs makes for a comfortable fit with Schwander’s own roaming sound.

“Detlef Toulouse Low Trax was the guy who tried to play everything else besides techno,” Schwander says of the brains behind the Salon. “He was very experimental and it’s because of the work he does every Saturday and every Wednesday in that club over years. I don’t know if it influenced the music, but it’s good to know that you can play it there. Always when I imagine how a track could sound when it’s really played loud with a PA, I imagine it at Salon Des Amateurs.”

Harmonious Thelonious occupies a curious space within electronic music, caught somewhere between armchair experimentalism and rhythmic reaction, and Schwander’s performance at Café Oto sits quite naturally in front of an almost fully seated audience, sandwiched between more explicitly ambient artists. On this occasion he holds back on quite so many of the intense drums of some of his recorded works and instead brings the fluttering arpeggios to the fore, but he reveals that he would prefer to play in a dance-orientated setting.

“My experience is, if it’s a good soundsystem my music works very well as dance music,” Schwander beleives. “Really, you don’t need always the four to the floor kick drum. I try to integrate a kick drum but it’s not the main instrument for me. It should be more funky in a way, and I think I can quite catch that vibe. It’s funky without being techno.”

While he has that feeling about his music, Schwander is also quick to recognise that not everyone feels the same way. It’s all too familiar a tale that event promoters will take a short-sighted view to avoid risk, even if it doesn’t tally with Schwander’s own experiences of playing in nightclub environments.

“To get bookings is not so easy because all the people say, ‘ah it’s not really techno it’s more like some difficult or crazy stuff’, but the people on the floor don’t see it as a problem,” he maintains. “They just go for it.”

The rhythms that Schwander works with, after all, have their roots in the foundations of ritual dance music, and while framed by standardised Western templates, those foundations still shape the music pounded out in clubs the world over weekend after weekend. It should be no surprise that, free of expectations, a crowd would respond instinctively as soon as they submit to something other than a familiar 4/4 thud.

Interview by Oli Warwick

Harmonious Thelonious on Juno