The In-Betweeners: Welcome To The Weevil Neighbourhood

James Manning joins the dots between drum and bass, dubstep and techno with Martin Heinze in The Weevil Neighbourhood.

ŌĆ£Katsunori Sawa for example is an in-betweener,ŌĆØ Martin Heinze says. ŌĆ£He doesn’t really do straight noise, or straight ambient, or straight techno, he doesn’t really do anything straight, what he does is something in between.ŌĆØ Heinze is talking about Yuji KondoŌĆÖs partner in the arcane collaboration Steven Porter. It was the duoŌĆÖs LR debut of 2011, described by German magazine De:Bug as ŌĆ£A MasterpieceŌĆØ that opened a wormhole into an unidentified field of music called The Weevil Neighbourhood, a fluctuating schism of paranormal sound design lurking within a free divide of techno, drum and bass, and dubstep.

ŌĆ£I don’t think I fully understand Leipzig and the music in general but the interesting thing about this city is it has an approach of anything leftfield,ŌĆØ Heinze says. His Berlin-based label, The Weevil Neighbourhood, continues an aesthetic Heinze recognises as an east German thing. Minor and Alphacut are operations central to what could be described as a Leipzig sound, with the 2001 established Minor supporting ŌĆśnoizŌĆÖ music, while Alphacut is GermanyŌĆÖs biggest exponent of drum and bass. Should wanderlust send you further into the uncharted world of the cityŌĆÖs experimental enclave, Flop Beat Disk is a semi-active, MS-DOS-themed alternative ŌĆ£dedicated to dirty formats and the worst genres inside the wide fields of electronic trash music.ŌĆØ

For strains of dub-inspired beat design allied with HeinzeŌĆÖs label however, 45 Seven, and more to the point Alpha Cutauri, are Alphacut sub-labels tapping into a current fissure of abstract club music derivative of drum and bass free of form, tempo and ultimately classification. Adding populous to this network are labels like Felix KŌĆÖs Hidden Hawaii and Geoff PreshaŌĆÖs Samurai Horo to ASCŌĆÖs Auxiliary, and individual as each labelŌĆÖs aesthetics are, all inhabit a ballpark space of similarly cross-fertilized club music that each call their own.

The Weevil Neighbourhood however hatched from the Weevil Series; three records introducing a conceptual theme of spatial relations, or topology, into HeinzeŌĆÖs project. ŌĆ£Basically itŌĆÖs the three development stages of the weevil; there’s the larva stage, the pupa stage, the adult stage,ŌĆØ Heinze says. German engineered dubstep, snarling half-time drum and bass, and tear out rave mechanics possess Larva and Pupa 12ŌĆØs. The Adult record, moreover, ultimately represents The Weevil NeighbourhoodŌĆÖs attitudes today through its rhythmic noise element, which, alongside two other uncanny lurches of syncopated ŌĆśbassŌĆÖ music saw Heinze for the first time embrace elements of freeform techno.

The Weevil Neighbourhood however hatched from the Weevil Series; three records introducing a conceptual theme of spatial relations, or topology, into HeinzeŌĆÖs project. ŌĆ£Basically itŌĆÖs the three development stages of the weevil; there’s the larva stage, the pupa stage, the adult stage,ŌĆØ Heinze says. German engineered dubstep, snarling half-time drum and bass, and tear out rave mechanics possess Larva and Pupa 12ŌĆØs. The Adult record, moreover, ultimately represents The Weevil NeighbourhoodŌĆÖs attitudes today through its rhythmic noise element, which, alongside two other uncanny lurches of syncopated ŌĆśbassŌĆÖ music saw Heinze for the first time embrace elements of freeform techno.

ŌĆ£At the point where the adult stage was reached I basically had enough contacts and distributors and shops and direct customers to be able to start a label project that wouldn’t collapse on itself,ŌĆØ Heinze says. ItŌĆÖs here the development stage takes on additional meaning. In 2011, with the year-long metamorphose of Weevil Series complete, Heinze created The Weevil Neighbourhood. ŌĆ£I had this website,ŌĆØ he says, ŌĆ£it was built up of single dots in different colours and different connections; I had green dots for the artists that worked for the label and black dots for the releases.ŌĆØ ItŌĆÖs the second time on the record IŌĆÖm speaking with Heinze, and this time over the phone he furthers the concept. ŌĆ£You could say this is a map of certain dots that are connected through certain characteristics, being music-wise or artist-wise or even time-wise.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs something of an image that helps me focus on the whole characteristics of the label itself,ŌĆØ he says, then, as if peeling away from a conversation too focused on artistic rationale, Heinze jokes, ŌĆ£anyway, most of the stuff I’ve said tonight is esoteric bullshit.ŌĆØ What HeinzeŌĆÖs conceptual paradigm aimed to signify, though, was connectivity through dispersion, be it artists and their respective locales, genre cross-pollination, physical formats for the music, to artwork and design. ŌĆ£In the beginning I always wanted half of the label more open, not focused on sound carriers for example, but also being able to branch out into different territories,ŌĆØ Heinze explains.

The Weevil Neighbourhood catalogues its releases by name not number, and as Heinze points out, it diffuses the label. ŌĆ£I like the image of something evolving from a less linear but more roomy kind of environment,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£The releases, in the best way, can breathe freely because they are not limited to linear development.ŌĆØ With catalogue names like AIR, DOTS and GRIDS to BLINDFOLD, PICNIC and COMPASS, comes added conceptual nuance, but more importantly it frees the label of a typical 001, 002, 003 inventory.

I first met Heinze in Berlin. It was early 2013 and The Weevil Neighbourhood, no longer adolescent but not yet fully formed, could be found comfortably holed-up in the experimental underground of German electronic music. Growing tired of the state Heinze found drum and bass, he expressed his aversion to the over-saturation of ŌĆśup-tempo breaksŌĆÖ. ŌĆ£Too fast, too intense,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£I found it hard to be surprised, either by the music, the events, the parties: the whole drum and bass scene,ŌĆØ Heinze told me. ŌĆ£I guess I was trying to find something that kept me fascinated, or interested, music-wise.ŌĆØ

Heinze is a respected drum and bass producer. As Martsman heŌĆÖs released records for Alphacut, Hidden Hawaii and Texan label Pushing Red, with straight up drum and bass coming through Breakin, Offshore and Warm Communications. Since my first meeting with Heinze heŌĆÖs stopped making music under that alias, and, he says, ŌĆ£I identify more with the label now.ŌĆØ During that first interview, Heinze, a well-spoken, well-mannered German, appeared hesitant to reveal too much about his own music, but over the phone 18 months later when asked if he, admittedly, still felt cagey talking about Martsman, he said, ŌĆ£when we met the last time, I was, on a personal level, between two phases, which was a sort of solo career in music, as well as running a label, which were two very different kind of things.ŌĆØ As a producer, Heinze believes it can be ŌĆ£more about putting yourself in front.ŌĆØ Now the artist formally known as Martsman takes sanctuary in The Weevil Neighbourhood where he can ŌĆ£keep in the background.ŌĆØ Furthermore, he adds, ŌĆ£it’s not that I work in that kind of field of music any more.ŌĆØ

Where does Heinze find himself then? ŌĆ£I’m not sure there are any particular words or genres I want to closely connect to the label but obviously there are certain influences in there,ŌĆØ Heinze begins. Attempting to put the sound of The Weevil Neighbourhood into words, he elaborates, ŌĆ£there’s obviously a lot of, let’s call it dubstep-influenced sounds in there, but there’s also jazzy, organic, almost rocky attitudes.ŌĆØ Heinze relates this to his website of before. ŌĆ£If you put three or four spots on a map for example, and say: this is techno, this is dubstep, and that is industrial and this is noise, then Katsunori Sawa or Anthone or Repetition/Distract, and all the other guys, are somewhat like in-betweeners,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£TheyŌĆÖre kind of where the lines connect between the dots.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Drum and bass was always something I was trying to reconfigure in a way that wouldn’t sound like drum and bass at all anymore,ŌĆØ Heinze reveals. HeŌĆÖs not alone. In 2011 Geoff ŌĆśPreshaŌĆÖ Wright of Samurai Music set up the Horo sub-label for a similar purpose. ŌĆ£Classification is the problem,ŌĆØ Wright says about the music he and the likes of Heinze, Horo artists Fis, Ena and Inigo, to labels Auxiliary, Hidden Hawaii and Alpha Cutauri are releasing. Earlier this year I find myself in Berlin again, this time with Wright, trying to understand more about this drum and bass metamorphosis. ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs the point,ŌĆØ he says, ŌĆ£when you do listen to it you are like, ŌĆśI don’t know what BPM this is and I don’t care because it has its own groove and flow, and that’s what’s so cool about it.ŌĆÖŌĆØ Wright adds, ŌĆ£it’s unclassifiable…or itŌĆÖsŌĆ”techno…you know?ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Drum ŌĆśnŌĆÖ bass has always been a hybrid anti-essentialist style,ŌĆØ music writer and author of Energy Flash, Simon Reynolds, wrote in his 1995 essay for The Wire, ŌĆ£The State Of Drum ŌĆśnŌĆÖ BassŌĆØ. Using Photek (Rupert Parkes) as an example, Reynolds believes, ŌĆ£Parkes’s reputation resides in having made Jungle sound more like ‘proper’ Techno and less like its own baaad self.ŌĆØ Reynolds, however, continues: ŌĆ£Straddling both genres without innovating in either, he’s infected Jungle with Trance’s funkless frigidity and pseudo-conceptual portentousness.ŌĆØ Manoeuvres labels like The Weevil  Neighbourhood and Samurai Horo are currently making donŌĆÖt always sit well with the staunch drum and bass faithful ŌĆō terms like ŌĆśarmchair hardcoreŌĆÖ were thrown around as a result ŌĆō but as Reynolds points out, ŌĆ£Parkes actually admitted in i-D that he and his posse ŌĆ£have more in common with Carl Craig’s music than we do with the majority of Jungle.ŌĆØ

Neighbourhood and Samurai Horo are currently making donŌĆÖt always sit well with the staunch drum and bass faithful ŌĆō terms like ŌĆśarmchair hardcoreŌĆÖ were thrown around as a result ŌĆō but as Reynolds points out, ŌĆ£Parkes actually admitted in i-D that he and his posse ŌĆ£have more in common with Carl Craig’s music than we do with the majority of Jungle.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£I think foremost the artists around dBridge and Instra:mental, Consequence, guys like that, are trying to break up the two-step thing, even though they wouldn’t totally leave it behind,ŌĆØ Heinze told me after I asked why tempo is referenced so much when explaining this music. This was also the case with Wright who used Yu AsaedaŌĆÖs recent Binaural LP to explain how the lines, and tempos, between drum and bass and techno can blur. ŌĆ£When you listen to Ena’s album there’s a tune on it which is 120-130 or something, but if you listen to it in the whole context of the album you don’t notice there’s a difference in speed.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£People get upset when artists who they consider drum and bass artists, who started as drum and bass artists, do something different and they don’t call it drum and bass,ŌĆØ Wright believes. ŌĆ£Then there’s this discussion you get into with them, like OK, it may be 85 BPM, but it doesnŌĆÖt have a breakbeat, it has a 4/4 behind it, so why is it drum and bass? Please tell me why it’s drum and bass.ŌĆØ

Wright singles out ASC as an early champion of the 4/4 beat structure set to an 85 BPM, lamenting its classification as drum and bass. ŌĆ£That ŌĆ£PolemicŌĆØ tune from ASC’s (Horo) single, which is basically an acid tune at 85, I sent that out to people and one very prominent drum and bass label owner actually just piped-up and said, ‘why are you sending me this, it isn’t drum and bassŌĆÖ,ŌĆØ tells Wright. ŌĆ£At the beginning I was a bit insulted, but then it just showed to me, he’s right, it’s not.ŌĆØ

ItŌĆÖs no longer taboo for drum and bass producers to crossover into straight up techno; Shifted, Trevino and Boddika are some high profile examples. Conversely, Manchester duo AnD, now known for their unrelenting brand of gabba-hard industrial techno, threw themselves back into drum and territory by giving music to Horo this year, and Hidden Hawaii before that. ŌĆ£Now people write stuff for me,ŌĆØ Wright says regarding the sub-label. ŌĆ£People are like, I’ve got a Horo for you.ŌĆØ

But like Reynolds warned in ŌĆÖ95 for the essay ŌĆ£Ambient JungleŌĆØ, which draws parallels with todayŌĆÖs hybrid exchange of dubstep, techno and drum and bass styles: ŌĆ£there are dangers in hardcoreŌĆÖs shift towards a slightly self-conscious ŌĆśmaturityŌĆÖ.ŌĆØ Reynolds expands, ŌĆ£itŌĆÖs ironic that some of JungleŌĆÖs experimental vanguard resort to the same rhetoric once used–by evangelists for progressive house and intelligent techno–to dismiss ardkore as juvenile and anti-musical.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Say between the end of the ’90s till 2002, 2003,ŌĆØ Heinze begins, ŌĆ£everything was pretty much based on the two-step break, and just in the last three or four years things have changed radically for drum and bass.ŌĆØ Heinze explains, ŌĆ£this kind of experimental side of drum and bass got around pretty much, and artists these days are producing that sound which would have been considered out of prox and experimental-sounding just a few year back.ŌĆØ Now, he says, ŌĆ£they’ve reached the bigger labels and I don’t think it’s that noticeable anymore.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£The Weevil Neighbourhood has been in the mid-tempo spectrum without being too much techno, but without being too much dub…step…or anything like that, or dub music in general,ŌĆØ Heinze says. ŌĆ£I think what really interests me is a certain framework of tempo, for example, or certain aesthetics, but these aesthetics arenŌĆÖt totally replicable.ŌĆØ Heinze believes this perspective comes from an urge to introduce a certain vocabulary to the drum and bass frame, which, he says, ŌĆ£at the point I started writing drum and bass, it wasn’t that present or vogue.ŌĆØ

Repetition/Distract, Anthone and Katsunori Sawa make up HeinzeŌĆÖs weevil neighbourhood, and room for Yuji Kondo will be made should Steven Porter return. ŌĆ£I love working with a limited amount of artists,ŌĆØ Heinze says. ŌĆ£That personal relationship in one form or another is crucial to my approach to label work.ŌĆØ After hearing the track ŌĆ£DeedŌĆØ by Steven Porter (by the way of an Electronic Explorations mix) from 10 LabelŌĆÖs various artist Mu EP, Heinze remembers, ŌĆ£I instantly felt it was something I wanted to have on the label.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£It was rhythmic to some extent, you couldn’t really decipher what tempo it was,ŌĆØ Heinze says. ŌĆ£It didn’t matter at all,ŌĆØ he adds. ŌĆ£It was extremely intense, there was a wall of sound, there was a bit of rhythmic structure and that was basically it,ŌĆØ Heinze says. ŌĆ£I mean mind-blowing, obviously, it was extremely inspiring for me as a musician as well.ŌĆØ That LR record ŌĆ£kicked open a few doors for me,ŌĆØ Heinze adds, and he says, ŌĆ£it is really important to have these guys on board.ŌĆØ

One door opened to Japan, home of Sawa and secret figure Anthone. ŌĆ£These guys, they all know each other, they all meet and probably write music together in different combinations and what not,ŌĆØ Heinze says. ŌĆ£Steven Porter was definitely a bridge to Japan and it was definitely, for me, a possibility to reach out to other artists that kind of wrote a similar sort of music or had a certain, same, mindset when it came to music,ŌĆØ he says, ŌĆ£music creation in general.ŌĆØ

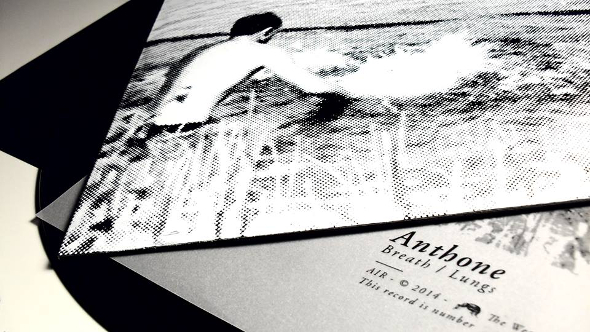

Anthone debuted on The Weevil Neighbourhood in 2012 with two records helping define the labelŌĆÖs initial sound of earthily crunch and mechanical abnormality. In 2014 the reclusive alias released Breath / Lungs, a record looking to a more spacious, broken beat dub techno aesthetic of digital-ish timbre. ItŌĆÖs a sound, Heinze says, the label will continue to mine, a sound he suggests is ŌĆ£very steady, digitalŌĆ” less earthy, sterile in a way.ŌĆØ That Anthone 12ŌĆØ in particular entered a grey area between drum and bass and dubbier club techno Hidden Hawaii explored with this yearŌĆÖs Nautil Series, three records Felix K explains as ŌĆ£a retrospective view on Hidden Hawaii Digital.ŌĆØ

Taken from a separate interview with Felix K to be published on Juno Plus in the near future, he explains, ŌĆ£at that time we felt the need for reduction, because music from the drum and bass genre pointed to several dead ends.ŌĆØ He adds, ŌĆ£while the mainstream seemed to be focussing on reproducing the same but louder version of different sub-genre blueprints, we headed back to the elements that made electronic music interesting to us.” For Felix K, “it was the warmth of dub chords combined with warm bass sounds,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£It led us to a more universal thing than just the essence of drum and bass.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Think more Steven Porter and less Felix K,ŌĆØ Heinze says of his labelŌĆÖs potential sonic development, referring to AnthoneŌĆÖs latest record as ŌĆ£not too full, it’s pretty striped down,ŌĆØ adding, ŌĆ£stuff that I have in mind for the label is more dense.ŌĆØ Looking back and one of The Weevil NeighbourhoodŌĆÖs boldest records was Repetition/DistractŌĆÖs Salles Des Perdus. Released in 2012, its six interlinked ŌĆśtracksŌĆÖ combine a mixture of foley recordings and gloaming ambiences with the high frequency squeak of a cameraŌĆÖs flash recharging, to acoustic instrumentations draped in reverb made to sound all the more sentimental. ItŌĆÖs a misty record which feels as though it was recorded around a creaking shipyard. ŌĆ£Obviously it has ambient elements in it,ŌĆØ Heinze says of Salles Des Perdus, ŌĆ£but it’s not like a fully thought through ambient album or something like that, it’s more like a very volatile, unstable kind of sculpture,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs almost a storytelling thing.ŌĆØ

Over a six-month period Repetition/Distract sent The Weevil Neighbourhood bodies of sound Heinze ŌĆ£chose from, but loosely chose from,ŌĆØ he explains. ŌĆ£I kinda like that part because it’s not track-based, but you know the music,ŌĆØ Heinze says. ŌĆ£It’s not that he writes tracks and I choose from them, it’s more like he’s writing music, like itŌĆÖs patch-based.ŌĆØ Heinze continues, ŌĆ£so he’s recoding elements of the music, then he’s creating patches with software and hardware and whatnot, and he combines two worlds, or different elements into single pieces.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£HeŌĆÖs a bit of a hermit,ŌĆØ Heinze adds, describing Repetition/Distract as less clandestine than Anthone. ŌĆ£It’s kind of funny,ŌĆØ Heinze says, ŌĆ£we both live in Germany, we’ve known each other for more than ten years now and all of our musical relationship goes through email and it works perfectly.ŌĆØ Repetition/Distract is another artist Heinze says is connected to Leipzig, a place on earth Heinze reaffirms: ŌĆ£itŌĆÖs always a point of reference for me.ŌĆØ

Felix K agrees. ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt know why, but it seems that Leipzig is a good place for artists with a distinctive vision,ŌĆØ he says, suggesting people like Kassem Mosse add to the Leipzig phenomenon. ŌĆ£He is combining unique sounds and rhythms, showing an absence of mainstream influences and puts a good DIY feel to his releases.ŌĆØ This is something The Weevil Neighbourhood, through HeinzeŌĆÖs artistic vision, strongly echoes. ŌĆ£I think this in-between stuff is probably, but I’m not really sure about it, something for people who were close to the music scene, or even people who were producers or DJs developing something for themselves as a safe haven for good music,ŌĆØ Heinze believes.

ŌĆ£It wasn’t really important if it was deriving from techno or deriving from drum and bass or anything like that,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£All of these people were sort of drawn together in the faith that every single genre has more to offer than what a broader community of people would think it could bear.ŌĆØ

Interview by James Manning

All imagery provided by Weevil Neighbourhood

Juno Plus Label Podcast: Weevil Neighbourhood┬Ā

1. Thomas Carnacki – Elegant Things, Distressing Things, Things Not Worth Doing (Alethiometer)

2. Repetition/Distract – Salles Des Perdus: Untitled Pt. 4 (The Weevil Neighbourhood)

3. Katsunori Sawa – NGM (The Weevil Neighbourhood)

4. Demdike Stare – A Tale Of Sand (Modern Love)

5. Shackleton – The Drawbar Organ (Woe To The Septic Heart)

6. Autechre – Stud (Warp)

7. Peder Mannerfelt – Expanding Sineways (Peder Mannerfelt Produktion)

8. Repetition/Distract – Salles Des Perdus: Untitled Pt. 5 (The Weevil Neighbourhood)

9. Shelley Parker & Paul Purgas – Chance Fracture (We Can Elude Control)

10. The End Of All Existence – The End Of All Existence (The End Of All Existence)

11. Steven Porter – Deed (10 Label)

12. Katsunori Sawa – Phenomenon (The Weevil Neighbourhood)

13. BOKEH – Void Armour (The Weevil Neighbourhood)

14. Anthone – Double Dub (The Weevil Neighbourhood)

15. Shackleton – But The Branch Is Weak (Skull Disco)