Free Flight: An interview with Shawn O’Sullivan

Scott Wilson talks to Shawn O’Sullivan, one of New York’s most exciting new techno producers and a man of many aliases.

“I would occasionally go terrorise the local youth centre by putting on 200BPM records or just straight up noise until someone complained,” Shawn O’ Sullivan recounts, describing his earliest DJing experiences in the unlikely location of Fairfield, Iowa when he was a teenager. Although now dubbed “silicorn valley” thanks to the numerous startups that reside there, when O’Sullivan was a teenager growing up in the mid-‘90s it was a Midwestern town most notable for being the largest training centre of the Transcendental Meditation movement, whose celebrity exponents include David Lynch and Clint Eastwood. Not exactly the most likely place to spawn one of New York’s most interesting new techno producers. “Getting kicked off the decks was quite a joy for me, it was an accomplishment,” he laughs, with no small amount of pride.

O’Sullivan’s furious brand of techno for labels like The Corner, Avian and L.I.E.S. may only hit the comparatively modest speed of 130BPM, but its relentless energy is obviously something that has its roots in the only way O’Sullivan could find to relieve the teenage boredom felt growing up in this sleepy Midwestern town. “It’s a weird place” he laughs, speaking over the phone from his current base in New York, where he has lived for almost 10 years. “It was pretty intense, it’s a small community of meditators in the middle of a cornfield, and the rest of the community are Midwesterners, ‘real Americans’. Of course when you put a bunch of weirdos in the middle of ‘real America’ there’s gonna be some friction, definitely. I felt very much an outsider growing up in that community, not having very much interest in Transcendental Meditation, and having absolutely no connection with the native Iowans. I was definitely beat up regularly.”

The current O’Sullivan sound sits somewhere between the early ‘90s NYC industrial style of Adam X, the well-honed techno of Ostgut Ton heavyweights Dettmann and Klock, and the darker, more experimental textures of Shifted and the rest of the Avian camp. His way into dance music however, was through America’s nascent pre-EDM ‘90s rave culture, which has since gone largely forgotten or undocumented. “This was the mid to late ‘90s, and in the Midwest, if you were interested in music, you were interested in electronic dance music, the same way a lot of people I knew who grew up on the East coast in Boston or Philadelphia wound up into hardcore. That was just sort of local youth culture,” he explains.

Although the type of music played at these events was varied, with filter house, the techno of Jeff Mills and Robert Hood and ghetto-leaning Underground Construction label’s music all featuring, as O’Sullivan explains to me, “being a bit of a weirdo, I was drawn to the most extreme forms of electronic dance music I could find.” This heavier form of dance music was something that filtered through to O’Sullivan from the neighbouring state of Wisconsin, where the legendary Drop Bass Network parties occurred both in Milwaukee and the state’s remote northern wilderness, away from the unwanted attention of the authorities. Although O’Sullivan admits to being a little too young to go to any of these raves, or to Milwaukee which was the main place to hear this type of dance music in the Midwest during the ‘90s, the music and its surrounding culture nevertheless had a profound effect on his tastes as a teenager, which were primarily gabber, breakcore and noise. This was reflected in his first musical experiments in high school with his brother and cousin, with the three using two turntables, a cheap DJ mixer with a built-in sampler, a two dollar microphone, and a cassette deck to create what he describes as “predictably awful” noise/collage-based productions.

Although the type of music played at these events was varied, with filter house, the techno of Jeff Mills and Robert Hood and ghetto-leaning Underground Construction label’s music all featuring, as O’Sullivan explains to me, “being a bit of a weirdo, I was drawn to the most extreme forms of electronic dance music I could find.” This heavier form of dance music was something that filtered through to O’Sullivan from the neighbouring state of Wisconsin, where the legendary Drop Bass Network parties occurred both in Milwaukee and the state’s remote northern wilderness, away from the unwanted attention of the authorities. Although O’Sullivan admits to being a little too young to go to any of these raves, or to Milwaukee which was the main place to hear this type of dance music in the Midwest during the ‘90s, the music and its surrounding culture nevertheless had a profound effect on his tastes as a teenager, which were primarily gabber, breakcore and noise. This was reflected in his first musical experiments in high school with his brother and cousin, with the three using two turntables, a cheap DJ mixer with a built-in sampler, a two dollar microphone, and a cassette deck to create what he describes as “predictably awful” noise/collage-based productions.

In the early 2000s O’Sullivan relocated to New York state where he attended Bard College for four years, where he took Interdisciplinary Studies, though as he explains, it was DJing which was his main creative outlet during this time. It was also where he seriously began to experiment with production, predominantly using a laptop with Reason, Fruity Loops and what he describes as “some feeble dabbling in Max/MSP”, though bits of gear he obtained or borrowed included the Juno 106, Nord Lead, Korg Polysix, MPC2000 and Alesis HR-16. “But really, in the early 00’s,” he explains, “if you were taking yourself ‘seriously’ as an electronic musician, you weren’t using gear. You used Max.”

After he dropped out, he made the logical move to New York City, where he immersed himself in the city’s underground music scene and made firm friendships with WT Record boss William Burnett, whom he had previously known from the now defunct forum of the Netherlands-based DJ collective Global Darkness, and future collaborator Sam De La Rosa, who played at Burnett’s ISS parties in the city alongside Jacques Renault, which O’Sullivan describes as “the first party I went to in NYC that I truly loved.” It was with De La Rosa that O’Sullivan began making music under the name Led Er Est in 2006/7 along with Owen Stokes, an electronic three piece with its roots in classic minimal wave sounds. It was an experience that was to prove invaluable in terms of his own practice. “I had pretty much stopped making music for about 3 years after college, because I was sort of creatively stuck. When I eliminated the laptop, suddenly everything started flowing.”

During the time, both were regular attendees of the city’s Wierd Records parties, which were a meeting place for similarly minded artists such as Martial Canterel, and future collaborator Beau Wanzer. This, along with the ISS parties, offered an alternative to the nu-disco scene which had taken over the city’s underground nightlife at the time, and provided O’Sullivan with the experience which  would go into his later projects, as well giving him as a regular place to DJ. “In 2007 I think it was, the Wierd Records party moved from Williamsburg to Manhattan,” O’Sullivan explains, “and that was my home for a good number of years. That was really just what was exciting, both in terms of old music being explored and integrating it with new music, and there was this very… kind of vital culture, sort of removed enough from the primary trajectory of New York nightlife culture. It was this wonderful little bubble.”

would go into his later projects, as well giving him as a regular place to DJ. “In 2007 I think it was, the Wierd Records party moved from Williamsburg to Manhattan,” O’Sullivan explains, “and that was my home for a good number of years. That was really just what was exciting, both in terms of old music being explored and integrating it with new music, and there was this very… kind of vital culture, sort of removed enough from the primary trajectory of New York nightlife culture. It was this wonderful little bubble.”

Although O’Sullivan has been producing since he was a teenager, and has found success with Led Er Est, it’s only in the last few years that he has started to make a name as a solo artist under a wide range of aliases including Vapauteen and 400PPM, as Civil Duty alongside fellow L.I.E.S. artist Beau Wanzer, and under his own name. Although each of his aliases undeniably have their own distinct character, it can be difficult to determine exactly what sets each apart. “I’ve always made a lot of different types of electronic music, but I don’t like to necessarily draw sharp genre distinctions between the different projects that I do,” he explains.

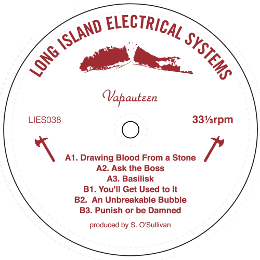

Despite not wanting to draw these distinctions, it does seem that he approaches each project with very clear boundaries. The first record as Vapauteen, which appeared on a L.I.E.S. white label in early 2012, was a driving industrial effort in the Regis mould, which largely preempted the subsequent flood of similar sounds which emerged later in the year. The most recent EP as Vapauteen for L.I.E.S. however, is a different beast, slowing the pace down to a leaden crawl similar to the productions of Andy Stott or Skudge duo Fishermen. The 400PPM record on Avian meanwhile, is as fast as his first Vapauteen record, and contains similarly grizzled ambient soundscapes.

With parameters such as tempo seemingly shifting within one alias, and techno being the dominant mode across most of them, how exactly does each differ? “With Vapauteen and 400PPM I think they’re sort of delineated by specific timbre palettes and attitudes more than a sort of stylistic concern” he explains. Or, to put it more simply, Vapauteen is “much more forwardly vicious”, he says with a knowing laugh. “I mean, for me it’s all related. Every project has its own parameters, but I don’t like to be easily confined or summed up too readily. All the projects are just sort of part of my own development. They’re all connected in my mind.”

O’Sullivan’s work as 400PPM, as well as his material with Beau Wanzer under the Civil Duty name for Anthony Parasole’s The Corner label has a relentless motion and keenly realised sound that could as easily be mistaken for the contemporary techno of Dettmann and Klock as it could the ‘90s output of Adam X. Are these artists an influence at all, or are the sounds that come out of his jam sessions accident rather than design? “I pay attention to it as much as I can – I love all sorts of music,” he explains. “I follow Dettmann, I follow the Ostgut stuff, but I tend to move away from things when they get too wilfully big room. That isn’t to say I’m against dance music – I think that’s one of the higher callings that music can aspire to, is to compel people to move. There are a number of lines that are very vague, but they can be crossed when things get a little too – for lack of a better word, ‘big room’. Then I don’t connect with it, but yeah, dance music is a good thing in my books.”

O’Sullivan’s work as 400PPM, as well as his material with Beau Wanzer under the Civil Duty name for Anthony Parasole’s The Corner label has a relentless motion and keenly realised sound that could as easily be mistaken for the contemporary techno of Dettmann and Klock as it could the ‘90s output of Adam X. Are these artists an influence at all, or are the sounds that come out of his jam sessions accident rather than design? “I pay attention to it as much as I can – I love all sorts of music,” he explains. “I follow Dettmann, I follow the Ostgut stuff, but I tend to move away from things when they get too wilfully big room. That isn’t to say I’m against dance music – I think that’s one of the higher callings that music can aspire to, is to compel people to move. There are a number of lines that are very vague, but they can be crossed when things get a little too – for lack of a better word, ‘big room’. Then I don’t connect with it, but yeah, dance music is a good thing in my books.”

Although O’Sullivan’s performance focus was predominantly focused on DJing in his earlier years, as he explains, his primary interest now is performing “hardware live sets that are as close to wholly improvised as possible.” Although his recorded work seems to take one idea and closely focus in on it, his live performances a a little more freewheeling. “I go in with occasionally a few rudimentary sequences or a vague idea of what I’m doing, but I like to work as immediately or as completely in the moment as I possibly can. It’s always a challenge figuring out an approach that is going to be as live, improvised, and flexible as possible, but also dynamic, engaging, and danceable. I’ve been really into some of the Keysound/130 stuff, and the Livity Sound material recently, and the idea of incorporating elements from the bass and hardcore continuum into my live set is very intriguing to me right now.” Having honed his set in the USA over the last few years (this set for Blowing Up The Workshop offers an excellent example), this February and March will see him embark on his debut solo live tour of Europe which will take him to Berghain among other places.

In terms of studio setup, O’Sullivan admits to paring it down in recent years, but he still currently owns a wide variety of vintage synths from the ‘80s and ‘90s, as well as a modular system comprised of a lot of Eurorack modules, which he rates highly thanks to their comparative affordability. “As it grows in popularity there is obviously a concern for these sounds, getting hyped or overly mined,” he explains, “but the tools are out there right now, and they’re exciting. But any tool is only as interesting as the person using it.” Given the increased number of people currently switching to hardware setups, is O’Sullivan worried about being lumped in with the hype of these sounds rather than on his own merits? “I think I deliberately do a lot of things both consciously and subconsciously to make it not so easily pigeonholed,” he explains. “I definitely have worked under a fair number of different names to express specific ideas as well as to avoid being trapped, so…yeah, I do think about what my music might sound like in 5 years or 10 years. I definitely aspire to make things that age well!”

O’Sullivan might be gaining attention thanks to productions which have caught the ear of many influential figures in the techno realm and beyond, yet it’s by no means the only string to his bow, with an EP under his own name for William Burnett’s WT Records standing out as one of his more intriguing documents. The Free Flight EP – like the rest of his material – defies easy categorisation, though it’s undeniably lighter in tone than his other solo work, having more in common with Burnett’s pastoral kraut-inspired electronics under the Black Deer alias than anything from Berlin. “It’s lighter, it’s obviously melodically driven, it’s a little more playful, but tinged with melancholy,” he explains of the record. “Part of that is just Will (Burnett). The label head’s role as curator can very heavily influence the way a record comes out. But that said I do like doing melodic stuff.”

Outside of his solo work, his current concern is Further Reductions, a minimal wave, italo disco and pop-inspired collaboration between himself and his partner Katie Rose (pictured above), who has been living with for the last six years. “Collaboration was sort of inevitable,” he explains, “we both love music, and we’re living together in a small apartment full of records and synths. The project is really just built around the dialog that Katie and I have going. It’s always been very open format. Katie’s very specific about her vision. I mostly follow her lead.” Although they have only released one 7” for Captured Tracks and a cassette for Robert & Leopold so far, the pair have their debut album coming on Minimal Wave’s Cititrax label in coming months. As well as that album, there are already talks of another solo record on Avian and a further 12” on The Corner with Beau Wanzer later this year.

It would be difficult not to see O’Sullivan’s music as part of a wider resurgence of techno, but it feels like he has been waiting quietly for years for trends to cycle back round again, without the cumulative baggage of the past attached. “I guess there have been some cultural shifts in the States, we’re more into dance music now than we were,” he explains. “People of my generation mostly grew up hating dance music – rave culture was despicable, it was the butt of jokes, you couldn’t say “I’m into techno”, you had to attach some disclaimer to it: ‘I’m into techno but only this kind’, or ‘I’m into techno but not what you think’. You couldn’t say ‘techno’ – that was very much a dangerous word, and sort of justifiably, because dance music culture in the States was always pretty bad.” Although O’Sullivan is talking of the country’s obsession with EDM, he feels New York City specifically has seen an upswing in the enthusiasm for the kind of techno he makes, with the continued efforts of The Bunker parties being complimented by smaller events at the newly opened Bossa Nova Civic Club, and Aurora Halal’s consistently adventurous Mutual Dreaming parties.

However, it becomes clear throughout our conversation that although his love is dance music – techno specifically – O’Sullivan isn’t particularly concerned what type of music he makes as much as he is gaining mastery over his machines. “I kind of went through a long period of not wanting to do anything with any kind of melodic content, but I think I might be partially coming out of that,” he explains of his current headspace. “I don’t like feeling trapped. I want to revisit some of those ideas and concepts I was working through with the first WT record with the tools and the knowledge that I have now. But yeah – also to some degree, my ear’s tired a little of spartan, militant monochrome techno, just at the moment,” he explains teasingly. “But I’m always open to exploring any ideas.”

Interview by Scott Wilson

Header image by Ilaria Pace