“Everything takes longer when you’re older”: An interview with Richard H. Kirk

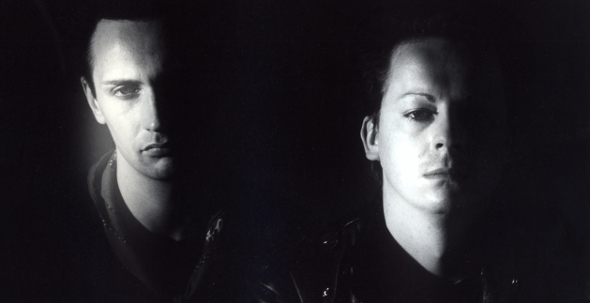

In advance of #8385 (Collected Works 1983 – 1985), the first of several Cabaret Voltaire boxsets planned for release by Mute Records, the iconic band’s central figurehead and spokesman Richard H. Kirk speaks with fellow Steel City curmudgeon and Juno Plus writer Matt Anniss.

Maybe I’ve read him wrong, but Richard H Kirk has always given the impression of being one of electronic music’s true originals – an eccentric with a burning passion for doing things differently. The first time I interviewed him, way back in 2001, he turned up to meet me dressed in an army surplus jacket, with shoulder length purple hair, carrying a stack of obscure white labels under one arm. As we sat down, he handed me a record – one of his notoriously challenging Deconstructed Trance Anthems releases – and matter-or-factly said that he would be surprised if I managed to get to the end without turning it off.

For the record, I did. As we talk, 12 years on, I remind him of this. He laughs. “That’s nice to know,” he says. “I actually heard someone playing one of those tracks in a DJ set not long after that. I was really pleased with that, because it wasn’t the easiest of releases.”

That’s an understatement. But then Kirk is famously understated, something that was no doubt ingrained in him when he was growing up in Sheffield (the Steel City does dour understatement better than anywhere else on Earth). He has also forged a 40-year career in electronic music out of challenging perceptions, standing up to the establishment (in musical terms, at least) and channelling his righteous anger into a series of acclaimed projects.

Much may have changed in the 12 years since we last spoke, but Kirk is still living the life of an electronic recluse. His once famously productive work-rate has slowed a little – “Everything takes longer when you’re older,” he says, “especially if you work on your own like I do” – and his releases are far more sporadic, but he still feels a burning desire to make music and challenge the perceptions of a whole new generation of listeners. “I’m still excited about making stuff – if I wasn’t I wouldn’t do it,” he asserts. “It doesn’t earn me phenomenal amounts of money, so I must still enjoy it, otherwise I’d go and play a computer game or something.”

Whilst Kirk may at times seem tired and irritated, he’s happily lost none of the burning rage and bloody-minded attitude that marked out his time with Cabaret Voltaire, one of electronic music’s most obtuse, thrilling and out-there bands. Talking on the phone from his home in Sheffield, where he has lived – sometimes in blessed isolation – for all of his life, Kirk flits between cheery reminiscence, weary frustration and out-and-out anger.

“It frustrates me that there’s a lack of dissent from young people today,” he growls. “It actually upsets me that this is where we’ve arrived at. The Internet might be very liberating, but I think it’s also a major reason for the lack of dissent right now. People seem to spend half their time watching things on YouTube and on Facebook. They’re not living in the real world any more – they’re living in a virtual world. The things that are happening with this government, they’re worse than Thatcher in the ‘80s.”

He sighs, pauses and then continues. “I think the only people who can fight back are the hackers. I’m not condoning any of that and saying it should happen, but if there is any fight back, it’s most likely to come from that area. I just don’t see any other form of dissent.”

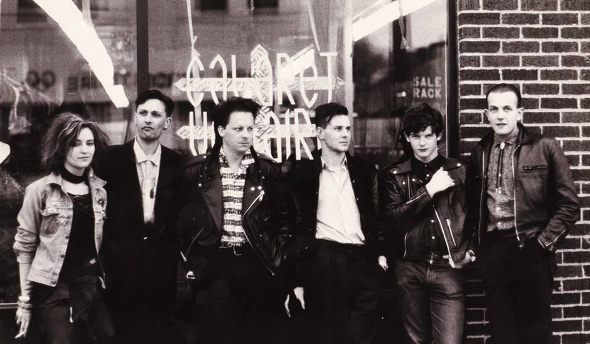

The idea of dissent is something that has always been important to Kirk and his former Cabaret Voltaire band mates Chris Watson (now a world renowned sound recordist) and Stephen Mallinder (now an academic in Brighton). When the trio first began to make music in Watson’s parents’ attic in 1973, they famously boasted of a bloody-minded desire to “piss people off”. Inspired by a curious mix of 1960s soul, distorted American garage-rock and the droning synthesizers of krautrock, they spent their formative years in Sheffield doing things differently – so differently, in fact, that their weird fusions of distorted guitars, home-made electronics and tape loops regularly left Sheffielders bewildered, puzzled and angry.

The idea of dissent is something that has always been important to Kirk and his former Cabaret Voltaire band mates Chris Watson (now a world renowned sound recordist) and Stephen Mallinder (now an academic in Brighton). When the trio first began to make music in Watson’s parents’ attic in 1973, they famously boasted of a bloody-minded desire to “piss people off”. Inspired by a curious mix of 1960s soul, distorted American garage-rock and the droning synthesizers of krautrock, they spent their formative years in Sheffield doing things differently – so differently, in fact, that their weird fusions of distorted guitars, home-made electronics and tape loops regularly left Sheffielders bewildered, puzzled and angry.

“Being deliberately difficult is a big part of why we did it to begin with,” Kirk says. “We wanted to fuck with people’s heads. You know, to have fun with strange noises. There wasn’t much going on in the local music scene. You’d got a couple of heavy rock bands and the rest of it was pub bands playing covers of chart material. Certainly locally there weren’t many – or any, that I can remember – doing what Cabaret Voltaire did in those days. We were out there on our own.”

In their early days, Cabaret Voltaire weren’t an easy proposition. It’s not surprising that they found it hard to get interest from record labels. “I have a stack of letters at home that I discovered when I was going through my archives, and we were sending tapes to major labels,” Kirk reveals. “Christ knows what they must have thought of it, because this was in the mid ‘70s when our music was at its most challenging. Most of the letters were polite refusals, saying ‘this isn’t the kind of material we’re looking for’. We had a good laugh about it at the time. I think they were kind of freaked out by us. At that point in time, before punk, there were no real independent record labels. So we just did what everyone else did and sent tapes to the majors. No wonder they turned us down.”

The story of Cabaret Voltaire’s early years and rise to prominence – the droning industrial oddness, warped guitars and processed vocals of debut full-length The Mix-Down, the anthemic growl of “Nag Nag Nag” and their curiously funky experiments for Belgian label Crepiscule – has been told many times. It’s their most celebrated period, and the one that music scholars return to most frequently.

Kirk, though, is here to talk about the next stage of the Cabs’ career, a three-year period following the departure of Chris Watson for pastures new at the tail end of 1982. It’s fair to say that music critics tend to be a bit sniffy about the band’s output during these years, due in part to their relocation from leading independent label Rough Trade to Richard Branson’s Virgin Records (a deal struck following Kirk and Mallinder’s decision to sign with Soft Cell’s management company, Some Bizarre). This attitude from the press still rankles with Kirk, who returns to the subject several times during the interview.

“A lot of people say ‘Cabaret Voltaire weren’t any good after Chris Watson left’,” he fumes. “I’m not naming any names, but there was a recent article in a magazine that more or less rubbished everything I’d done, and Mal and I had done, after that. They said everything after 1981 was crap. That hurt. There seems to be this idea that we moved to Virgin for money and spent all this cash on clothes and eyeliner. That’s absolute rubbish!”

It’s easy to understand Kirk’s frustration, especially as he’s just completed compiling an expansive box set of the band’s Virgin-era work – including many previously unreleased nuggets and alternative versions – which is due to drop on Mute in early November. It took him nearly two years to complete.

“It’s been very time consuming,” he admits. “I got sent the Virgin Cabaret Voltaire tape archive in January 2012. I had to go through that and make sure we were getting exactly the right production masters. Then those masters had to be baked and digitized. Then I had to go through the unreleased stuff and put that together. I’ve also worked very closely with the designer, doing frame grabs from the rushes of videos and films, a lot of which hasn’t been looked at for 30 years. It’s taken a massive amount of my time. Hopefully people will be interested.”

Titled #8385 Collected Works 1983-85, the box set comprises Cabaret Voltaire’s three studio albums from the period (The Crackdown, Micro-Phones and The Covenant, The Sword & The Arm of the Lord), all of their singles (including the essential 12” versions), two DVDs featuring unseen live shows and the previously VHS-only Gasoline in your Eye long-form video, and a 12” single featuring various hard-to-find tracks. Oh, and the small matter of a CD featuring previously unheard material originally recorded for the soundtrack of a proposed – but sadly never completed – film called Earthshaker.

It’s perhaps this never-completed soundtrack, with its strange ambient textures, discordant electronics and industrial attitude, which will most appeal to hardcore fans. It also proves, contrary to conceived wisdom, that the Cabs’ were still experimental to the core throughout the Virgin period, despite their attachment to a major label.

“That was a side of Cabaret Voltaire that got downplayed a little bit in favour of tracks with vocals on – more conventionally structured tracks,” Kirk admits. “It was always my idea that the ambient and experimental side of what we were doing would be channeled into soundtracks. That’s what happened with the Earthshaker stuff. If you listen to Gasoline In Your Eye there’s a lot of instrumental stuff that made perfect soundtrack music. It’s a real shame that it didn’t get developed further, really.”

Alongside the previously reissued (and remixed) soundtrack to 1983 film Johnny Yesno (a bleak study in addiction with an even bleaker soundtrack), Earthshaker and Gasoline in your Eye are the sole surviving examples of Cabaret Voltaire’s flirtation with films, and in particular the opportunities offered by video technology. During the period covered by the box set, they spent much of their time championing the potential of video – both by reinventing the music video as a piece of twisted art (see Peter Care’s brilliantly out-there video for the 12” version of “Sensoria”, which ended up in New York’s Museum of Modern Art), and founding their own label, Doublevision, which specialized in releasing both 12” vinyl and VHS videos.

“We knew that there was something to be done with that technology,” Kirk reminisces. “The first ever long form video we did, Doublevision presents Cabaret Voltaire, that’s how it came about. There were these really crude pieces that we were able to edit together on these two VHS recorders. When home video first came in, there was this flood of ‘video nasties’, which didn’t require certification at the time. That interested us because it meant we could put anything out on video and we wouldn’t get prosecuted. Of course Thatcher changed that a little later on and they did tighten up the rules where videos did need certification, the same way as film did. But for a short period it was totally open… and open to abuse I suppose.”

“There seems to be this idea that we moved to Virgin for money and spent all this cash on clothes and eyeliner. That’s absolute rubbish!”

Kirk and Mallinder’s motivation for their video output was, like with their music before it, a desire to challenge orthodoxy and push the boundaries of what was acceptable. It was, as Kirk points out, another form of dissent; “The job of any artist should be to challenge the status quo,” he states. “What happened in the 1980s is that the counterculture was destroyed by money and greed. I remember in the ‘70s, when Cabaret Voltaire came across anyone who we’d call a Bread Head – i.e anyone who was getting into music to make money – we’d give them a wide berth. Sadly as we got to the mid 1980s, that became it – glamour, success, that’s what people were aspiring to. That’s stayed and become the norm. That’s really sad.”

This is, we should point out, an accusation that has been leveled at Cabaret Voltaire during this period. According to the narrative put forward by the Wire and others, Kirk and Mallinder deliberately tried to become more of a “pop band” during their Virgin years (not to mention their later ill-fated stint at EMI). Kirk refutes this, though he does admit that they were encouraged to push Mallinder’s vocals to the fore. “Part of the deal with Stevo and Some Bizarre, was that he said he’d give us £10,000 to record in a studio, if we recorded an album where the vocals weren’t so processed and are a bit higher in the mix. I guess in terms of presentation, Mal did become the front person, and I kind of lurked in the background. For me, that’s exactly how I preferred it.”

It’s a harsh accusation, and one that Kirk has clearly heard too many times. He laughs loudly at the suggestion that their major label bosses tried to market them as some kind of industrial funk version of the Pet Shop Boys. “If only we’d had the record sales of the Pet Shop Boys – I’d be living on a Caribbean island by now,” he chuckles. “The Pet Shop Boys were pure pop and were very good at it. We just weren’t. We couldn’t write pop songs.” That maybe true, but there’s an accessibility and incessant funk to the Cabs’ Virgin recordings – and particular their 12” singles – that was often lacking in their earlier material. By this point their greatest inspiration was dance music, and in particular the bold 808 rhythms of New York electro.

“What something that people forget about the Cabs is that during the ‘70s we were going out and dancing to James Brown and the Fatback Band,” Kirk says. “It was always music that we loved, but we never felt we could make music like that because of our limitations. When we started using sequencers and programmable drum machines, it became something within our grasp. We heard all of the electro stuff from New York and thought ‘this is futuristic’. A lot of it was more interesting than so-called experimental music. I guess we were drawn to it. To me, it just seemed natural. Where do we go now? Well, here, to the dancefloor.”

There’s an argument to be made that Cabaret Voltaire’s 12” singles between ’83 and ’85 – from the cut-up madness of “Coma” and woozy, slo-mo proto-techno of “Safety Zone”, to the rush-inducing rhythms and backing vocals of “Sensoria”, and the pulsating electro science of “Kino” – are amongst their best work. Certainly, they were hugely influential, with many of dance music’s American pioneers (most notably Derrick May and Juan Atkins) citing them as a huge influence. “I only found out that we’d inspired people like Derrick May and Juan Atkins about 10 years ago, when we put out the Conform To Deform box set,” Kirk reveals. “They were both very complimentary about the ’83 to ’85 period. I thought: that’s one in the eye for all the fuckers who say the ‘80s Cabs period was no good’.”

Fittingly, Kirk was in turn influenced by the sounds of Detroit – and, of course, the music being made by Unique 3 up the road in Bradford – when it came to record the Cabs’ later albums, and most famously his bleep-era work, first with DJ Parrot as Crooked Man, and later with Warp founder and local bass legend Rob Gordon as Xon. “You know that Rob mastered the first ever record in Sheffield?” Kirk asks. “It was a Sweet Exorcist record we did after we left Warp. That Xon record we did [The Mood Set on Network, 1991] was recorded over about three days at Western Works. Rob brought all over his analogue stuff – he had some really old analogue sequencers and keyboards. We just set it up and did it. It turned out really well. We actually signed a deal to record an album on the back of it, but sadly it never happened.”

Fittingly, Kirk was in turn influenced by the sounds of Detroit – and, of course, the music being made by Unique 3 up the road in Bradford – when it came to record the Cabs’ later albums, and most famously his bleep-era work, first with DJ Parrot as Crooked Man, and later with Warp founder and local bass legend Rob Gordon as Xon. “You know that Rob mastered the first ever record in Sheffield?” Kirk asks. “It was a Sweet Exorcist record we did after we left Warp. That Xon record we did [The Mood Set on Network, 1991] was recorded over about three days at Western Works. Rob brought all over his analogue stuff – he had some really old analogue sequencers and keyboards. We just set it up and did it. It turned out really well. We actually signed a deal to record an album on the back of it, but sadly it never happened.”

Since the demise of Cabaret Voltaire – though, it should be noted, Kirk still plans to use the name again, having fallen out with former studio partner Stephen Mallinder some years back, a separation that only be described as “complicated” – Kirk has divided his time between dancefloor-focused material and more dubwise electronic fare (see his Sandoz productions). These days, though, he has less time for dance music than he once did.

“Most of it’s rubbish,” he asserts. “I call a spade a spade. It’s just so bland. Technology is great, as is the democratization of making music. We did that in our own little way – we shouldn’t really have been making music. The difference is, with us it came from the heart. It was something we really believed in. It wasn’t something we did just because we could. That’s the difference now – anyone who’s got a laptop can download some software and away you go. I despair at a lot of laptop-created music. It’s just so clichéd – so much of it is the same.”

Happily, Kirk does get excited by some new music, and admits to having a soft spot for Factory Floor, an outfit whose ethos, sound and style is heavily inspired by both Cabaret Voltaire and Throbbing Gristle. “Put it like this: Factory Floor is one of the best bands I’ve heard and seen in a long time,” he enthuses. “Last year I DJ’d for them and afterwards I had a few drinks and watched them play live. I was totally blown away. They were using all the visuals and all this analogue gear. They just got deep into these great grooves – it really did remind me of Cabaret Voltaire, with a little bit of Throbbing Gristle thrown in. I thought ‘fucking hell, here’s somebody who’s got it’. It really cheered me up. I thought ‘these people get it’. What they’re doing is great. I hope if they’re touring they come to Sheffield, because I’d love to see them again.”

Kirk admits that he’d love to collaborate with them – “I’d just love to take my guitar down to the studio and jam with them over some great grooves” – and has suggested just this to Nik Void and company. He’s still waiting to get the call. “They’re probably too busy,” he says, ruefully.

There’s an air of resignation about Kirk’s attitude throughout the interview. At 57 years of age, he seems to think that his time is running out. “I may not be around much longer,” he says. “That’s why I wanted to do this box set now, before it’s too late.” He sighs deeply. “Maybe I’m a grumpy old man, but listening to stuff now and stuff from the past, I know generally what I prefer. You do from time to time get stuff that’s really exciting, but there’s so much that’s bland or uninspired. It’s probably because it’s all made with computers. That’s probably why it all sounds too similar.”

He pauses. “Maybe I’m just not open enough.”

Interview by Matt Anniss

#8385 (Collected Works 1983 – 1985) is released by Mute on November 11 – more details here.