A Life In Sound: Borai’s potted guide to Bristol

Bristol based producer Borai takes Oli Warwick through the various record shops, club nights, individuals and institutions from the city that have helped shape his sound.

Bristol based producer Borai takes Oli Warwick through the various record shops, club nights, individuals and institutions from the city that have helped shape his sound.

As soon as you meet him, you’re not likely to forget Boris English. His boundless energy bowls you over in a barrage of facts, anecdotes and all-round enthusiasm for most subjects, but most of all music. As a Bristol resident all his life, Boris has arguably been raised by the music scene of his city, guided through his formative years by that quintessential West Country cocktail of rumbling low-end and spiritual purity, steadily maturing in his tastes and knowledge and moving with the stylistic shifts that have naturally occurred since he first became possessed by the beat.

The past year or so has seen a definitive culmination of those years of dedication, via a series of lauded releases with sometime studio brethren October on such labels as Apple Pips and BRSTL, and now taking full flight with a solo 12” used to herald the start of Chicago label Tasteful Nudes. It’s a decidedly house-orientated thread that has started to define the disseminated sound of Borai, but truthfully Boris’ musical background comes from a disparate range of exploits and undertakings that tell a humble story of the Bristol scene away from the media frenzy that has occasionally gathered around key artists in the past. It’s an experience that speaks out for the many unsung heroes of any local scene, from those that do little more than pop into the record shop for a chat once a week to the tireless, flyer-loaded promoter hustling people to the dance.

Through his various engagements with music on an assertive level, Boris provides a neat snapshot of some of the hidden treasures a city like Bristol has to offer. It’s not so much about the artists the city has been made famous for, but rather a celebration of a life dedicated to music on a local level, where it matters the most.

Prime Cuts & other Bristol record shops

It would be easy for even a keen-eyed record hunter to miss Prime Cuts. Were it not for the sandwich board jutting out onto the bustling treadmill of Bristol’s Gloucester Road, you might never know it was tucked away in the basement of Repsycho. The steady stream of students and party people looking for vintage threads are just as likely to glaze over the little door that leads downstairs, its poster-plastered door jostling for attention amongst garish shirts and classic jackets.

Once you do find yourself in Mike Savage’s record shop though, it’s easy to envisage hours sinking away in front of you as the compact cellar space bristles temptingly with reams of records across two rooms, stacked high, deep and far. If the spread of genre sections seemed daunting enough, one glance at the cash desk and the fit to bursting room behind it is enough to ensure full-blown vinyl fatigue sets in. Endless towers lean precariously next to each other, some bagged up for job lot shipments, others awaiting guidance after being dropped off by someone looking to de-clutter their life. This shop is a constant celebration of the ephemera that defines us, filling every space made by a sale with an instant replacement for fear of exposing too much wall space.

Stock wise, it’s a canny selection that Mike offers in his twelfth year of trading, with a healthy balance between pleasant surprises and trusty classics on most trips to hunt out wax. It’s not the same kind of bottom-dollar digging you can enjoy in charity shops, but equally you’ll have to sift through a lot less dross and if you’re not precious about mint condition, you may just get a bargain.

Mike represents an archetypal contributor to the music industry, honing his multi-tasking skills and thinking creatively in order to carve out a living. His formative Bristol years were spent as a prolific promoter, packing in as many nights as the week could give him.

“Bristol used to be Monday to Saturday,” he recalls as we stand around in the shop at the end of a sweltering summer day. The warm conditions bring out the comforting mustiness of a second hand record shop, and it fills every corner of the room. “You could put on a night on a Tuesday and fill it, and now it’s different. Everything’s free. Free things are nice but it devalues music I think.”

“Bristol used to be Monday to Saturday,” he recalls as we stand around in the shop at the end of a sweltering summer day. The warm conditions bring out the comforting mustiness of a second hand record shop, and it fills every corner of the room. “You could put on a night on a Tuesday and fill it, and now it’s different. Everything’s free. Free things are nice but it devalues music I think.”

When he was done with promoting and DJing, Mike’s insurmountable stack of records and the vacant basement space under Repsycho arose as a possible new avenue to pursue. “We opened in 2000, and Boris was coming from the start,” Mike recalls, turning to look at his partner in dusty record dealing. “How old were you?”

“Oh god from about 17 I used to come in here,” Boris exclaims.

“Him and Jules (better known as October) used to come in, fresh from the night before and just bouncing round the shop. It was like a crèche,” Mike chuckles.

“Jungle and drum & bass were the first new records I was buying,” Boris explains of those early days, “I’ve always had an interest in second hand stuff. Down here it was the funk section that I was going through quite a lot and again second hand drum & bass records.

“And a bit of nu jazz I seem to recall,” Mike chimes in.

“Lots of nu jazz!” Boris proclaims enthusiastically, “and then lots of things to sample too.”

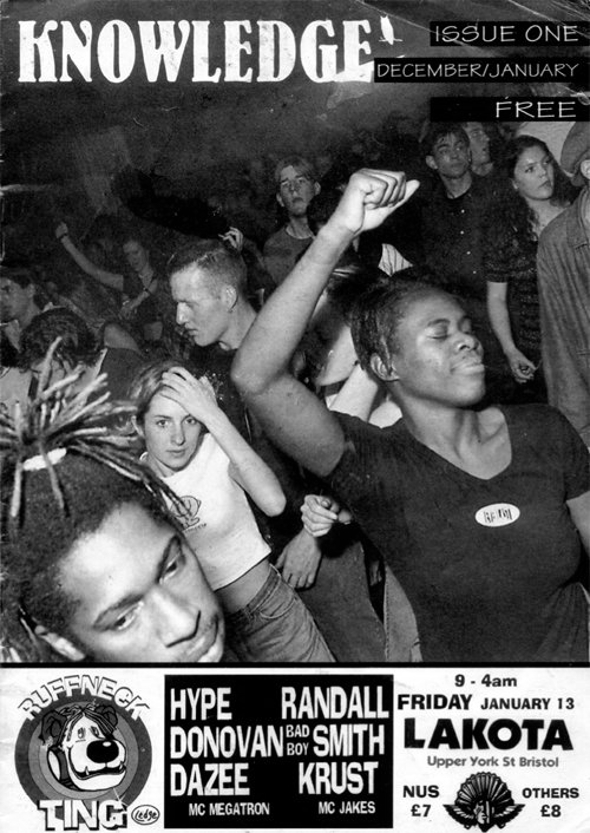

Before he was dipping into the world of crate digging, jungle was Boris’ first love and he spent his formative record buying days in Breakbeat Culture, a shop that used to reside in the back of a clothes shop (notice a theme here?) named Cooshti on Park Street, right in the centre of town. BC was run by the same team behind the seminal Ruffneck Ting nights that represented the vital advancements Bristol was making in the business of sped-up breaks, and it stood proud as Bristol’s only dedicated jungle shop.

“I went in there when I was 14 or 15,” Boris remembers, “and I was just getting into it. They didn’t have any listening turntables, so you had to ask them to play any record you wanted to check on the big soundsystem, and that just meant that there were those horrible moments of, ‘what have I picked?! There’s ten people in the shop and arrggghh!’ One time, I can’t remember what it was but I picked something and played it and there were nods from everyone in the shop. That was the moment I was like, ‘oh it’s ok, it’s fine, it’s good enough’!”

“Good music is timeless. The Invada thing is timeless. Massive Attack is timeless, and the same now with Tectonic, Punch Drunk, Idle Hands.”

After a few changing of hands and location switches, Boris wound up working at Breakbeat Culture before it ceased trading, although in his words it was more a chance to, “turn up, keys to the place, rant out jungle music all day.” Before all that though, Boris could be found serving the Bristol populace from the age of 15 in the decidedly less edgy surroundings of the Virgin Megastore in Broadmead.

“I was given the jazz and classical department on a Saturday,” Boris says of his formative training in the world of record shops. “I was given my own soundsystem and allowed to play jazz and classical music so I went, ‘ooh jazz, fuck classical,’ and I started at A and went all the way through.

What used to be the Bristol Virgin Megastore has become symbolic of record shops’ position on the high street, changing ownership quarterly and dredging through unwanted stock from a netherworld of forgotten musicians who never quite struck gold. It still limps along now as Head, with a sizable vinyl section packed full of future charity shop material at bargain bin prices. As with all these places, there’s still a chance you might get lucky somewhere in between the scores of disposable funky house and breaks 12”s, but its days as a spot on the record shopping circuit are numbered.

“When I first arrived in Bristol there were about 18 record shops,” Mike guesses of the good old days, “or maybe more. I think there were one or two which I never even found, but getting on for 20 actually, and what is it now? Seven if that?

Jungle and the nature of the Bristol scene

Back when he was in his mid teens and getting a taste for vinyl, Boris was usually found combing the plethora of record shops that centred around Park Street in the mid 90s. As well as Breakbeat Culture, he speaks of picking up on house in Bang Bang, not to mention digging in Eat The Beat, Giant, Tony’s and Purple Penguin.

“You don’t know Purple Penguin?! Man! That was an institution!” Jules ‘October’ Smith exclaims. It’s a torrentially wet Thursday evening and we’re sat in The Mothers Ruin under the dim glow of skate videos while a band sound-checks badly downstairs. “Skateboards and hippity hoppity. That’s also where I discovered house music. I got a few Carl Craig bits, some Paperclip People and some 69 bits. I didn’t think that those records would be techno or whatever. I used to think that techno was something completely different.

“Bristol has a long history of techno but it has a long history of nosebleed, banging techno,” Boris explains, thinking wistfully back to clattering gabber mixes by DJ Fade heard on ropey fourth hand tapes at school. However it was jungle that brought Boris and Jules together after meeting at Breakbeat Culture while Jules was working behind the counter.

At that time, jungle was the main currency in Bristol clubs, much in the same way dubstep and more recently house music have been representing the city globally since. “Essentially you had two big crews,” Boris explains of the scene as it was in those days. “Full Cycle started a bit earlier. If memory serves me correctly Breakbeat Culture was people coming to university and starting something, like half of all Bristol residents, whereas Full Cycle were born and bred so they had a few years above Marky and Darren.”

Full Cycle of course had international repute, spearheaded by Roni Size and his avalanche of critical acclaim that helped break jungle and drum & bass into the wider public consciousness, but the Marky and Darren that Boris refers to were known at the time as Decoder & Substance, later to become chart-hassling hybrid favourites Kosheen. While Breakbeat Culture was their shop, their Ruffneck Ting parties were the definitive snapshot of the nascent jungle scene, and the accompanying live tape series featuring the likes of LTJ Bukem, Randall and Hype circa 1995 has attained something of a mythical status.

“I went to a few Ruffneck Tings,” Jules recalls. “They were pretty rough, pretty scary. The first thing I went to though was a Ganja Kru thing at Powerhouse. That was like ‘96, so it was still really jungly.” The heaviness of the parties at the time is widely agreed upon, but by the time Boris joined in there was another go-to destination for all those needing a D&B fix. Drive By was run by Gerard and used to take over Level, a long lost club near Park St, and The Thekla, an iconic nightspot for Bristol on an old cargo boat that still packs out gigs and club nights every week to this day.

“I went to a few Ruffneck Tings,” Jules recalls. “They were pretty rough, pretty scary. The first thing I went to though was a Ganja Kru thing at Powerhouse. That was like ‘96, so it was still really jungly.” The heaviness of the parties at the time is widely agreed upon, but by the time Boris joined in there was another go-to destination for all those needing a D&B fix. Drive By was run by Gerard and used to take over Level, a long lost club near Park St, and The Thekla, an iconic nightspot for Bristol on an old cargo boat that still packs out gigs and club nights every week to this day.

“Gerard used to drop free passes to all the record shops, a very clever man,” Boris remembers. “He’d bring the big drum & bass guys in, and it was wicked. In the end we all stopped going to it ‘cos it was just full of children, but what I realised was at that kind of age range two years is quite a lot. I had a lot of conversations with people who would say, ‘yeah Drive By is just full of kids.’ And when were you going to it? ‘When I was 17’.”

“We were just young, enthusiastic, going out all the time,” Jules says of those days, “but I soon got very disenchanted with the whole thing. It was a very aggressive atmosphere at the parties.”

Of course with age the need for tribal loyalty to a particular scene wears off, and so both Boris and Jules grew and explored their own paths through a diverse spread of beats. Whatever the case their approaches have always shied a little from the zeitgeist at any given time, but now their own idiosyncratic takes on house and techno find themselves associated with a wider tag of Bristol house music, perceived by some as the critically admired operations of labels such as Idle Hands, but also by many as the widespread success of acts such as Julio Bashmore and Eats Everything.

“I never felt any real affiliation with any scene in Bristol until the last couple of years,” Jules muses, “and that’s only because what we’ve been doing is suddenly popular elsewhere. Idle Hands, Pev, Kowton, that whole little crew, that’s what I feel that Bristol is really like.”

It’s true of many underground music scenes around the world that the perceived success of the protagonists from outside is quite often a far cry from the day to day reality on the ground. “Back in the day, you had Nick from NRK putting on Richie Hawtin at Thekla and 30 people turning up,” Jules continues. “Paul Purgas from Emptyset put on Underground Resistance at the Arc Bar years ago, and no-one ever talks about that! I worry now that there is this idea of Bristol house music that is really popular and there’s so much hype on it; it all seems a bit faddy. Good music is timeless. The Invada thing is timeless. Massive Attack is timeless, and the same now with Tectonic, Punch Drunk, Idle Hands.”

Of course this perspective reflects just Jules and Boris’ own experiences of partying, DJing and living in Bristol for most if not all of their lives, when there are countless tributaries of subcultures at work at any one time, populated by enthusiastic heads from first-timers to seasoned pros. Like any self-respecting urban enclave, it’s the mixture of these pockets of culture that make up the ambience of the city’s creative corners, and there’s no denying Bristol has had a healthy injection of such self-reliant imagination over the years.

Cutting dubs, spinning wax

Cutting dubs, spinning wax

If there remains one constant through so much of Bristol music culture, it must be vinyl. Even as digital technologies tempted many away to a life of convenience, a strong contingent of the dubstep community made a specific point of sticking to wax. Buoyed by the soundsystem undercurrent that has always emanated from the Jamaican population of the city, the likes of Pinch and Peverelist were (and still are) religiously cutting dubplates of exclusive material, both maintaining the tradition and making a defiant statement in their commitment to it.

Henry Bainbridge is one of those dedicating themselves to the preservation of vinyl culture, both with his Wuk Up parties but most significantly with Dub Studio. Based off the beaten track in suburban Bristol, overlooking a nature reserve no less, Henry lives with his family on the top two floors of his house while the basement is given over to two rooms that make up the studio. From there he masters and cuts both vinyl and acetate, whether it be a dubplate or a 78rpm jukebox record.

“My inspiration for the name Dub Studio was taken from a book about dancehall culture,” Henry explains, “which described how a ‘dub studio’ was a focal point for many facets of the music industry. I never wanted to just process audio and transfer it onto vinyl, or fire digital files across the net, I wanted to be part of what’s going on around the music.”

With Wuk Up operating as an extension of the Heatwave collective once a month at The Bank on Stokes Croft, Henry is certainly active in engaging with the music beyond his studio, committed to pushing the true sound of dancehall. “Dancehall is always bundled together with other genres like reggae, jungle, dub and even roots,” Henry explains. “I wanted to do a night that was all about dancehall, without having to rely on other genres to prop it up. I sometimes think we might be freaking some people out a bit, but the harder the dancehall we play, the more people love it.”

Having crossed paths through an assortment of musical endeavours, Boris and Henry got chatting at Shanti Sound, a party Boris, Rapid and Embassy were putting on some four years ago in Cosies, a cellar bar in St Pauls. With a shared passion for dancehall and Boris’ unbridled willingness to learn, a plan was hatched to bring Boris into the fold at Dubstudio.

“We currently have more space than before,” Henry explains, “and I’m finally in a position to train Boris up on running a lathe. It’s been in the pipeline a long time, about three years now, but Boris stuck around and made it happen, which not many people are willing to do these days.”

“I’m going over there for weekly sessions and at the moment it’s cutting stuff for me!” Boris beams about the tutelage he receives from Henry. “With the use of the lathe on evening sessions I thought, ‘why not cut my stuff’? Then it gives me a way to go, ‘boom, it’s finished’, and I’ve got it on dub and I can play it on a mix or play it out.”

Certainly Boris’ sets around Bristol are peppered with dubplates, from the collaborations with October to bashy party riddims, but as he gains control of the craft he already sees further ways he can get creative with the ability to cut records. A recent post he made on Facebook showed a picture of a freshly cut dub entitled Battle Weapon 001, purportedly featuring a pair of new tracks of Boris’. The catalogue number can’t help but suggest the beginning of a series.

Certainly Boris’ sets around Bristol are peppered with dubplates, from the collaborations with October to bashy party riddims, but as he gains control of the craft he already sees further ways he can get creative with the ability to cut records. A recent post he made on Facebook showed a picture of a freshly cut dub entitled Battle Weapon 001, purportedly featuring a pair of new tracks of Boris’. The catalogue number can’t help but suggest the beginning of a series.

“It gives me an excuse to do things like preparing material to cut onto dubplate that’s special or very stripped down,” says Boris of his plans formulating around his burgeoning skill. “Eight minutes of one kick drum with nothing on it; that can be a kind of weapon, a battle weapon. That’s part of the idea, it’s not just forthcoming material.”

Boris’ passion for dubplate culture and everything that surrounds it isn’t hard to spot. You can see how much he romanticises the aesthetic as well as the practicalities of the format. At a time when there are ever fewer trained vinyl engineers, it will be the likes of Boris that the resurgent wave of vinyl lovers will be depending on to keep the wax spinning.

“One of the things I’m striving for is to be in a position to cut lots of dubs,” Boris says of his own ambition in the world of cutting. “Ideally my ultimate plan is to turn up with a ten inch record box that’s got nothing but dubplates in it. That’s the ultimate goal.”

Boris makes for a great example of the multi-faceted nature of being involved in music. There’s no question he has the energy for keeping up this spread of endeavours, but he also represents the discipline required to acquire a new skill. Along with patience it’s a quality you can sidestep and still get ahead in the digital age, but it’s reassuring to know that some people are focused enough to take the time and do it properly.

Interviews by Oli Warwick

Borai shots by Alex Digard

Ruffneck Ting image courtesy of Ruffneck Ting

Dub Studio photos by Lizzie Eve