Brennan Green: Escape from Chinatown

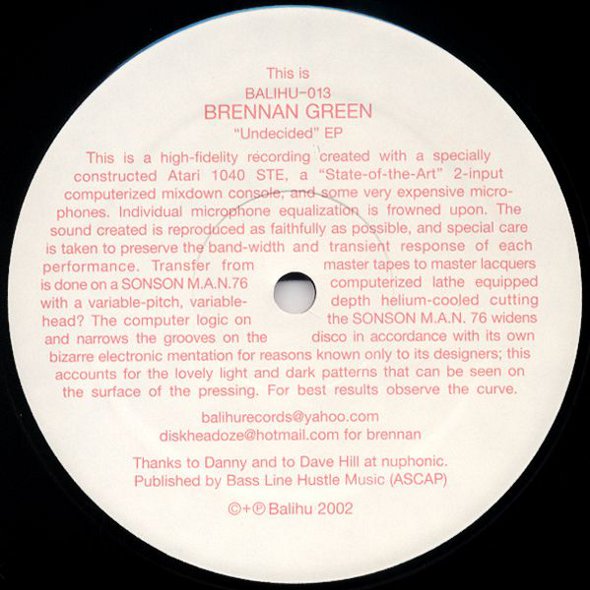

“Just because you can release something without a record label, which is now as simple as putting it on the internet, doesn’t mean you should. If you take it seriously, take some time to learn the art.” Pertinent words, especially when they come from someone who’s been in the game as long as Brennan Green. The New York based artist came to prevalence in the early 2000s, working closely with Daniel Wang and his Balihu imprint, before forging a close association with the Scandinavian axis of nu-disco a couple of years later.

Green quickly became known for learning the art of editing and sampling – his withering opinion of the current glut of Soundcloud dwelling edits is telling – and in 2005 he launched his own imprint, Chinatown Records, which has maintained a glacially paced release schedule of essential house and disco.

We sent our New York correspondent Nik Mercer to Green’s studio apartment for a wide ranging discussion in which the outspoken producer speaks openly about his devoted Scandinavian following, how “every joker and their mother is editing records and taking credit for someone’s genius” and much more.

What’s your musical background and what kind of stuff did you get into when you were growing up?

My older sister played piano and the organ. I got thrown into guitar first. Maybe that made an impression on me, but I definitely didn’t like it at first. Then I took drum lessons and that made more of an impression. I was young―eight or nine. When I went to high school I got back into guitar, heavily. This guy Shane who was a friend of mine showed me some riffs of songs I liked and I couldn’t believe he was actually playing what I was hearing. Then he got me into all this music―industrial and metal and stuff― so I bought a guitar and learned how to read tablature, leaned how to play my favourite songs. I started with piano by sitting down and literally counting off all the notes from the staffs above the tablature, trying to figure out the chords for piano.

That’s a tedious way to go about it…

So tedious. But when I’d play it, it was amazing for me to hear it happening at my fingertips – what a rush. I had such a hard-on for Ministry when I was learning guitar. Not the disco shit―the industrial shit. The Land of Rape and Honey, “Stigmata, Thieves”… I was a skateboarder. But, yeah, getting the tablature and playing it… I was like, ‘it sounds exactly like the song! I’m doing it!’ Then I got a drum machine, a Boss Dr. Rhythm, and programmed all the drums, from beginning to end. I would record myself― man would it be butter to have those tapes now.

I kind of gather you’re not from a big city.

What’s a big city? No, not Toronto. Niagara.

Awesome. So that was your adolescence…

That and petty crime. There’s not much to do in a small town except that, write graffiti and get into music. I’m really lucky it worked out the way it did for me back then. When you don’t have the control over your life like you do when you’re older, things can get hairy fast. When I hear about old friends and acquaintances, it’s never good.

When did you actually get to New York?

Well, I started DJing in Buffalo because it was so close to the border.

What, you’d drive to Buffalo and DJ for a weekend or something?

Yep. That’s where I met Master D and Kazoo and a bunch of guys who were going to U.B.― University of Buffalo. And Gringo ― Marcos Udagawa – was throwing raves in Buffalo and I started DJing his parties. Those guys finished university and moved back [to New York City] and were like, ‘you gotta move to New York!’ Before that I would also drive up to the raves in Toronto, too…that’s where I experienced the underground scene before I got involved in it. The rave scene was a big influence. I was lucky because Toronto was between Chicago, Detroit and New York. Later on, the West Coast… those guys started to get flown in with their breakbeat sound. Once I heard that, I couldn’t play a 4/4 beat for at least a year― it was completely boring after hearing proper B-Boy breakbeats.

How was the scene there?

Good – a healthy rave scene for sure. They had one of the biggest outside of London― maybe the second biggest. And definitely bigger than New York’s. Because it was English promoters coming over and doing it the way they were doing it there. This was like ‘90, ‘91, ‘92. Here, I guess you could say it was with Frankie Bones and [his] Storm Raves. I guess that was very similar but with a harder sound in the techno sense.

How did you get into DJing to begin with?

Raves.

So it’s guitar, drum machine, Ministry―

Yeah. This kid came back home from a rave and was like, You have to go check out one of these parties… it’s crazy, the kind of music they play. And I was like, ‘they can play this Ministry song there, right?’ It was “So What” and I play that still sometimes now. I even made an edit of it to play out – talk about full circle. I was so into that shit… I was 15. It didn’t make sense at raves then, but… it works when I play now. It’s psychedelic and repetitive and one step away from house music. But, anyway, [this kid], he told me, ‘no, it’s different’. In Toronto, we had hardcore, which was pre-drum and bass and jungle― not the hardcore in New York, where it was almost happy hardcore and hard techno. So we ended up going… and I remember looking at the DJ playing a jungle set and thinking― probably because I had no idea what was going on― I will never do that. That was the first thought I had: I couldn’t and will never do this.

That’s sometimes the way it goes. You have an initial distaste for something…

[Puts a cassette into a tape deck.] Last time I got my hair cut, I was in Toronto – I get my ex-girlfriend who always does it at her shop Barbarella. She gave me my mixtapes from ‘93. I’m gonna remaster them and post them. Some might be earlier than [‘93]. I recorded them [straight to tape] in my mother’s basement. I think is gonna blow some people’s minds― there’s some real great immature moments too; I was even scratching a bit. I made these all for her… Shelley. She emailed me recently to say she’d found more. These are from 20 years ago! I need to find some of these records again, I know I still have 99 per cent of them.

So you got into raves and that compelled you to start buying vinyl?

Yeah. We’d buy them from HMV, Sam the Record Man, and Play the Record, a place I wound up working at. It was so nice to be completely out of my element. My comfort zone was, like, skateboarding and the music that went with it― rock ‘n’ roll and heavy metal. Heavy metal was a whole new world. Suddenly you’re into a new sound and there’s a million bands to choose from already there. When I got into house music, even at that point it was still kind of young, so there wasn’t a ton. Now, there’s all these different styles and it’s evolved so much… but it’s all still house to me.

Yeah, today, you can zero in on a few things and sort of―

Find your own niche. But that gets boring fast, playing some microcosm of house music. The DJs I heard then and admire now manage to fit it all into their set, disco, house, blues, jazz, funk, reggae, techno, rock.

“Just because you can release something without a record label, which is now as simple as putting it on the internet, doesn’t mean you should. If you take it seriously, take some time to learn the art”

How else did you access music?

I was calling Record Time in Detroit, doing phone orders. They would just say, ‘this is cool―you need it.’ Done. Here’s my mum’s credit card number. I was 17 remember. She couldn’t figure out why all these records kept showing up a day after I asked to use it. You would just know everything inside and out when you receive a 12″ – it was so special you would study everything about it. Just like by the time the cereal’s gone you’ve read everything on the box. You’d have that crate― I still have my first milkcrate, the Beat Food crate! – and you’d get whatever you could get your hands on and learn it. I had a shitty mixer and some shitty home turntables without pitch control. Then I got some with pitch control, with a belt drive.

And when did you sort of notice the change when disco and house become more prevalent and accepted?

Well production-wise they were already doing it in London. Like, the Idjut Boys were doing it, Street Corner Symphony and Faze Action Other Records, the French, Motorbass et al. It was still really house-oriented, though; it was disco-influenced house whereas now it’s house-influenced disco.

House melted back into disco.

Yeah. So they were already doing it there, but the DJs here weren’t really. When I moved, the DJs had this very purist sense of house. Unless you played 4/4 beat with congas and those soulful house vocals, you couldn’t really get gigs at those parties. Also, there was the techno scene which was separated from house around the time; Alexi Delano was fusing techno and house together as it should be.

But it wasn’t like you were filling some gap, per se. There were plenty of parties…

There was plenty going on. I think we were trying to fit in with whatever we could, with what we knew. The sound that was really big then was… a lot of the New York house producers were doing that sort of smooth spiritual house sound, which sort of belongs in elevators more than it does the dance floor. That made house kind of boring for a while. A lot of guys were making these super smooth [productions]. I wasn’t into that.

When did you start really pursuing production seriously?

[I started] back in Toronto, but― I guess I started producing around ‘96. DJ’ing and producing sort of went hand-in-hand for me because it [took a while to] learn about [and acquire] gear. We’d go to the swap shops―what do you call them here?

Pawn shops?

Pawn shops. Yeah. Here, they mostly deal with gold. But I remember going in one and selling my guitar for the sampler, the workstation. Then I got the Atari, which was for external sequencing. And then another little sampler. Trial and error, man. Production was definitely a piece-by-piece thing. Cutting up records and sampling them, trying to make house music. I could never figure out how to make it sound so good… because [the established guys] had all the compressors and analogue drum machines and all the good shit.

Were you doing edits then?

Yeah. I wouldn’t have called them edits back then – I was cutting them up. I was working with a Roland W-30 with maybe 16 seconds of sampling time, so I’d sample everything on 45 and then slow it down to get more time and make grooves out of that. Not like today where you can just “sample” the entire song. I’m trying to get those old tapes back, too!

Do you look back on that production process as laborious?

It wasn’t, though, because we didn’t know any other way. I had that workstation and an Atari 1040ST with MIDIthen the Nord Lead came out. I got a mixing board, which I still have and an [Akai] S1000 sampler. I think DAT machines became obsolete the day after I dropped $500 on one. Anyone want a DAT machine? I can hear it now, “Daddy, what’s a DAT?” All my early records were mixed live. I’m really lucky in that sense that I spent three or four years tops before the technology became more accessible price-wise and the software began to explode. But I’m glad that I got that; it gave me a little character and [helped develop] a workflow. I basically used the computer just to record audio― most of it comes from the imagination and I barely use software synths. I record, edit and do arrangements on the computer.

And as I said earlier, I was super into rock and guitar, but when I discovered this whole rave thing, I swear to god, I didn’t pick my guitar up again. That was it. Well, until I got more into production and started recording myself. The exact thing happened when I got a laptop. I never turned my sampler back on, sadly. I had it loaded with my drums I had sampled from vinyl, all those drum hits and all those sounds I would use in every song I made! Like, if you go back to my old Balihu records, you hear it… everything was done with the S1000. I’m trying to get back into that when I have the time to reacquaint myself it, actually. I was given an S3000 a few years back I’m dying to fire it up.

Your first records came out in 2000 right?

Yeah, something like that. The first one was “Downstreamers,” on CSM, John Selway’s label.

How’d you meet Selway?

Through DJing in Buffalo. He taught me how to use a computer! Now he’s teaching New York how to use computers to make music. [Laughs] He was the manager at Satellite… he literally showed me what the internet was. Master D at Syntax got me an email address. So funny how it wasn’t that long ago for that stuff. I mean, I don’t even have a phone right now― everything’s on email.

Yeah, but you’re sort of unusual in that way. And when you last had a phone, it was that janky flip phone.

It was a Razr! Remember the early Motorolas? They were like walkie talkies.

I remember getting a Motorola Star TAC and thinking that was the shit.

That was New York City for me, cell phones like accessories. I knew one guy in Toronto who had a cell phone. We still had home phones.

Okay―back on topic! Let’s talk more about the CSM and Balihu stuff. How were you making those?

I’d sample drums, but not loops, and if I used loops, I’d cut them up. Build the song from beat one with no idea for song structure. Now, I use drum loops more than I did back then. I go for the rhythm box vibe where the old drum machines would only have a few select rhythms to play. I try to achieve that same vibe with sampled drum loops and build songs ontop of that hypnotic and repetitive rhythm. Back then, I’d program the drums to sound live to make up for my lack of musical sense. I’d spend months programming every nuance, every accent. They were not loops at all. I do less of that now because for me the importance and essence of the music take precedence over the rhythms; it’s a balance. I want to keep people’s attention with melody and harmony and not just interesting drum programming.

Anyway, the early stuff… I was sampling more and those were more like edits, but just bigger samples where I’d had drums and mix up samples from other records, layering. Still, though, I had a sort of filter for that; it felt like it was cheating to copy too much of a song. Even when I heard the Black Cock records back then I had no idea the songs where barely touched, I thought it was new productions. I really didn’t think people were or would do that. At least Harvey wasn’t putting his name all over them, a class act.

Nowadays, you can cut a vocal out of a song and call it your own. Every joker and their mother is editing records and taking credit for someone’s genius. I’m sorry but just because you removed that bridge with the corny chord change that might not work well in the current dance music climate doesn’t mean you can just take writing credit. It’s just asking for trouble. Then again it just goes to show the level of sophistication of the audience and whether or not it’s accepted for what it is or for what it’s trying to be, which in a lot of ways is fraudulent.

People seem to be using it almost as a proof of concept these days. Like, it’s not as important as it used to be to have a record or two under your belt in order to get attention and bookings. That was sort of your calling card… or your credibility card. The proliferation of SoundCloud and similar services allows you to circumvent that part of the equation if you want to.

Yeah, but there’s also no quality control anymore. All the stages a song would have to go through before getting released are gone or are going. I think that, nowadays, there should be, like, a basic course in music theory that people have to take before they touch [the software and equipment] that is around. If you love music and are interested in making it, why not learn a little something about it, it can’t hurt can it? After all, you’re so passionate about music aren’t ya? [laughs] I wish more people straight-up copied good shit. I tell people when they’re getting into production, if you’re not going to bother to learn anything about harmony or theory and you want to learn how to make good music – copy your favorite records to a T. Please rip it off! Try, it’s not as easy as you think, and you might come up with something different in the process. Learn how it was made inside out, do it yourself and go from there before you start releasing your own. Just because you can release something without a record label which is now as simple as putting it on the internet, doesn’t mean you should. If you take it seriously, take some time to learn the art. Now the software is so do-it-yourself that it lacks creativity, I’ve seen plugins make rhythms for you sans programming.

Sort of like what you do when you’re studying art, say. You copy the masters and learn the essential techniques… and then you do, like, your self-portrait and continue from there.

This is exactly what I’m talking about.

” I tell people when they’re getting into production, if you’re not going to bother to learn anything about harmony or theory and you want to learn how to make good music – copy your favourite records. Please rip it off! Try, it’s not as easy as you think, and you might come up with something different in the process”

It’s cheap and easy to get stuff made today and it’s cheap and easy to get music disseminated― and to a lot of people.

Yes, and it ends up sounding cheap and easy. And it’s easier to lie as well. Back in the day it was a skill to flip a sample. You were trying – to an extent – to bury it to hide it from other producers as well as not get sued. Like wild-style in graffiti, you’d fuck up those letters or that word until you couldn’t read it any more. Now these toys are blatantly putting their birth names on other peoples work! Without even attempting to hide the fact. And they get gigs out of this? Who knows maybe I’ll be honoured if it ever happens to me. Either that or I’ll be on a mission for blood and money! Before, it was about finding that sample and using it ahead of someone else; now it’s about finding the whole fucking song. That’s where the DJ came in. As a DJ you would dig and dig to find a song and play it to death, kill it… until your name was on it as a DJ. Nobody else could play it. It’d be like, Oh―that’s Nik’s tune. Why are you playing Nik’s tune? But you just have to be the first person to edit it. At least back then you weren’t taking credit for the music, only for playing it. It’s a funny time right now, for sure― anything goes, I guess. Hopefully it will eventually come back to creativity and originality. And there’s nothing original about editing someone else’s music that in most cases should never have been touched in the first place.

Also, the shelf life for songs now has sort of shrunk, I feel, especially in bigger cities that have some sort of obvious club culture. The time from when something gets introduced to the market until it becomes not cool is pretty brief. Something that’s really good versus something that’s shit versus something that’s maybe just mediocre― it all gets about the same amount of exposure time.

Well, it’s interesting because… something that’s good, sure, it might get played-out really fast. But the true test of time is finding something that after getting played out, can you still get away with playing it? Forever? There’re still lots of records in my bag― old Todd Terry records, for example― that aren’t in there because they’re trendy right now, but because they never left. I love hearing that acid house is cool again, every four or five years or so.

Okay― let’s talk more about your records. When and why did you start Chinatown?

What year? Can I look it up? [Laughs] There’s just so much time between every release that it’s hard to keep track. Quality over quantity! Oh, 2006. I started it to put my― and my friends’― tracks out and to have control. I worked in distribution and had all the connections it was an easy next step.

How many copies did you press for the first one?

I think 2,000.

And how many for the last?

Uh… 400? But it just came out two weeks ago. Give it some time. [Laughs] We press based on pre-orders these days. The one before that― the Arthur Russell one ―did 1,500, but after all it was a Loose Joint, joint. But when I started, there were six distributors in New York alone and now there’s just one. Actually, it all started because I had a song ― it was “Little Ease” ― and a friend of mine had a friend who was visiting from Taiwan, and he wanted to work in the studio. So I told him, I have a track I was working on and I have lyrics written― would you be interested in singing them in Chinese? He came over and we did it. At that point, Lindstrøm was just starting to produce and he got in contact with me. He said he was into the Balihu stuff, that he loved what Danny and I were doing, and offered to do a swap. It was all timing! I had that one song done… and then Lindstrøm was like, Let’s swap… so he remixed [“Little Ease”] with [Prins] Thomas. So I had this sort of strong release, I felt, and I just put it out. I did the same for him with “Pesto Og Kolera.” That came out super early on Feedelity.

You went to Norway to do stuff with them, right?

Yeah― I still have to put that out. [Laughs] That was, like, six years ago. We jammed once. It’s coming, it’s coming.

You went specifically for that?

No, I got a gig from Kango’s Stein Massiv. Ever heard of him? The original Fjordfunk. He reached out and got me a gig in Tromso, Norway. I was working with Danny (Wang) and we started doing remixes because he never wanted to do them. Nuphonic asked him to do a remix and Paper asked him to do a remix and I was like, ‘My God, Danny! How can you turn these labels down? They’re my favourite labels!’ So I forced him to do a remix, which led to Rune Lindbæk reaching out. That was crazy. Those Norwegians changed house music for me just like how Dubtribe changed it and now I was working with all these legends. It was almost a setback as much as it was an advance. So he reached out and asked for a remix, which we did, [for Romklang in 2002]. Then he called me up at Syntax and was like, Thanks for the remix―I love it. I was like, Cool… any time you’re in New York… And he called me back in half an hour. “I bought a ticket,” he said. “I’m coming to stay with you for two weeks!”. So Rune was the [introduction to the Scandinavian scene]. Then Lindstrøm, then Kango and Prins Thomas. I went over there, jammed on something in the studio with them. It was Thomas on drums, me on bass and percussion, and Lindstrøm on keyboards and guitar. We just went for it. [We played for] 20 minutes. It’s cool, but it needs to be re-arranged.

Awesome. Yeah, and then you kept doing stuff with the Scandinavians. Like, you did that Studio thing. How’d you connect with Dan Lissvik and Rasmus Hägg?

That first tour I DJ’d at his party with Anders Persson. I had connected with this girl from Malmo who was 17 at the time… she wanted to do an interview because I had the Pop Your Funk party at APT and she was really into the resurgence of Arthur Russell. At APT we were bringing everybody over. Maurice Fulton… Martin [Moscrop] from A Certain Ratio DJ’d, Andrew Weatherall came to do a post-punk set, and Adam X did an insane acid set once.

When did you start getting gigs abroad?

After I did the Pop Your Funk CD. That was like wildfire. Again, I was so lucky. APT produced it― it was supposed to be a promotional thing for the club. We made a thousand― maybe not even― sold enough to pay for it and gave the rest away, and then it went everywhere; everyone heard it. Jet Set Records in Japan repressed a whole bunch of them, too. Not long after that, people started posting their mixes online and people stopped making CD mixes. It wasn’t kitsch like it is now, you know just like how people are putting stuff out on tapes again, to be cool. Maybe it was the stars, maybe it was just luck, but it was good that I was able to get a CD out before people stopped buying them. Do people still buy them? After that, I started getting gigs. And the guy who first booked me in Japan, he was like, I got you a gig in Kyoto… maybe we can get you another one in Tokyo―that’ll be enough to pay for a ticket to get you over here. Then he called me back and was like, Actually, I’ve got a whole tour for you and it was because of that mix!

So Sweden and Japan are like second homes?

I love Sweden. Every time I go to Europe, I get over there. In fact, at one point, I was DJing there so much that someone in the paper wrote I was the most frequent and popular DJ in Sweden; ridiculous. I’m sure that lasted for a minute. Suffice to say I was going there a lot and met all the players. It’s the same withJapan. I’ve DJ’d in more places in Japan than I have all over the world. It’s all these little tiny places, where people are open – that’s where I’m drawn to.

Interview: Nik Mercer

Photos: Victoria Stevens