Kuedo: Pastures New

“I think everyone’s got a folk music album in them.” So comments Jamie Teasdale, only half-jokingly, as we talk about his current musical guise and what else he or any other musician may be capable of. “Kuedo itself is still a project name and as much heart as I try and pour into it, it still has its own life and identity,” he continues. “People have a potentiality to work in different forms and musical devices. There are so many aspects to a human being and it’s ridiculous to turn it down to one or a couple of genres and say ‘that’s me’.”

Jamie himself is an example of this theory in progress, as his musical career matures and expands to take on ever more varied forms. When your first notable appearance on the radar is as part of the monolithic dubstep weight of Vex’d, it takes some time to free yourself of those former associations and have your new ventures taken at face value.

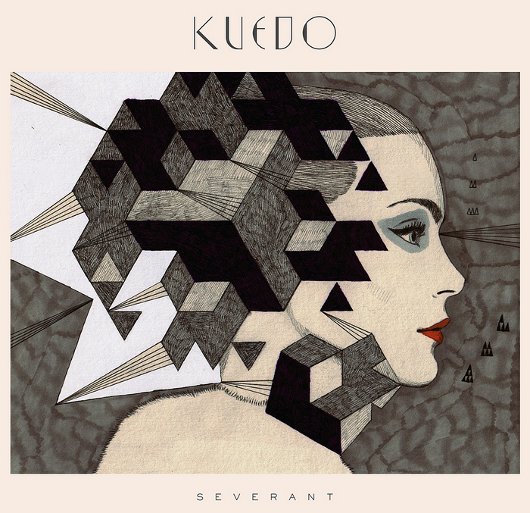

Listen to the spacious, elegiac Kuedo long player Severant, and you’ll notice a minimalist approach at work far removed from claustrophobic intensity of Degenerate or the In System Travel EP (released under the name Jamie Vex’d in the interim before Kuedo began).

“When the Jamie Vex’d record and the first Kuedo EP came out, I was interested in writing stuff that was quite dense and almost sloppy,” Jamie explains, wincing at his own use of the word ‘sloppy’ to articulate the freeform way in which the tracks were fusing together such myriad elements. “I was trying to eject a deliberate, slight ugliness in the music, and that had some meaning for me at that time.”

The first clear-cut appearance Jamie made as a solo artist was a remix of Scuba’s “Twitch” in 2008, which was a masterclass in colliding and exploding sonic matter full of deranged synths talking double-dutch to rippling bass swells. The Dream Sequence EP marked the first appearance of the Kuedo moniker, continuing to ply the heavy load beats that came before, bar a minute-long reflection entitled “Shutter Light Girl”. Although no-one would have guessed it at the time, this brief moment of hushed tones was pointing the way Jamie would head next with his music.

“Before I made the album I spent a lot of time rethinking what my intentions were behind it,” Jamie says, reflecting on the crossroads he found himself at before beginning work on Severant. “There was an experiment process for a couple of months where I was trying out different configurations of instruments and musical devices to hone in on where I wanted to go.”

“The album itself was more like an experiment, and one of the goals was to find a better way for me to capture what I was going for,” he continues. “I reduced the amount of tools I was going to use down to a specific amount, and also divided the phase of writing into an initial, very quick, recording stage, then a separate, slightly more thoughtful arrangement stage, and then a last mixing stage. It meant that I could capture the idea quickly without all the technical stuff getting in the way.”

In the everlasting battle between natural, impulsive creation and the barrier of music technology, it’s not always easy to find a practice that enables you to sidestep the distractions of endless parameters to tweak and realise an idea in its pure form. “That most vital moment is when you record,” Jamie states firmly, “and to me that is the time when you need to let go of all the intellectual frameworking and let your intuition guide the process. To that extent, when I record I try to play everything by hand and hopefully within the first few takes. It’s important to capture the idea while you have that inspiration. It normally comes on pretty strongly, but as time goes along the clarity of the inspiration begins to dissipate.”

The notion of minimalism in electronic music is certainly not a new one, although the early pioneers of hip-hop, house and techno, for instance, had the approach forced upon them by way of their limited means of production, rather than choosing it as a preferred working method.

“The stuff they [early electronic producers] had at their disposal was so limited compared to what we have now,” Jamie opines in deference to the forefathers, “and it’s awesome to realise how they made it work to their advantage to the point where it actually sounds way more dope than the stuff that’s coming out now with unlimited tools.”

Jamie is always keen to avoid getting too preachy about any chosen approach to production, but his perspective certainly has pertinence in an age cluttered with an abundance of tools and, as he would put it, “studio bloating”. “There’s an aesthetic that comes out of having a restricted palette,” he explains. “If you were to select a certain amount of instruments, then you would find something cohesive which would then tie in for a whole album.”

While there has always been a strong argument for limitations forcing artists to get more creative with the means at their disposal, Jamie’s true intentions come from a more emotive standpoint. When placed in the context of the evocative brushstrokes of pads and synths that dominate Severant, it makes perfect sense. “Even with the arrangement I wanted to restrict the amount of tracks within a tune to as few as possible,” he reveals. “I didn’t want to throw something in for sonic effect that had no actual emotional, imaginative meaning to me.”

To return to the aforementioned notion of audio clutter in modern electronica, Jamie can admit that the tendency towards bombastic displays of production prowess has the ability to create feverish responses in crowds, but it’s not a trend that he finds enjoyment in himself. “There is a certain amount of laddish studio tech competition going on,” he muses, “and it has affected some dance genres like drum and bass and dubstep, clearly. It’s like people are revving their cars at the beach strip, just showing off their horsepower, and it becomes a kind of noise battle.”

It could be argued that Vex’d, with the muscular and abrasive way in which they represented the earliest forms of dubstep, had some element of this pec-flexing to them. Anyone who has heard the likes of “Thunder” or “Bombardment Of Saturn” belted out over a club system will be able to attest to the seismic power the tracks contain, but Jamie’s motivation now lies elsewhere.

“If you’re going to write singularly dancefloor orientated tracks then that needs to be a concentrated intention, and once you focus on that you will cut out a lot of stuff that might cloud that intention,” Jamie states. “I didn’t just want to make or just listen to DJing music any more. For a long time I had the world of clubs and DJs factoring into the creative process to some extent but increasingly it’s becoming less of a main function and in this album I really let it go. I began to realise it was becoming restraining than doing anything good for me. I really wanted to make a more emotive listening album.”

It would be a cold ear that didn’t detect the heart and soul Jamie has poured into Severant, drawing on life experience that he would of course prefer to remain private. That said, the theme that has driven much of the public analysis of the album is that of ‘futurism’. With the influence of Vangelis and Tangerine Dream looming large, it’s understandable that ultramodern imagery gets readily associated with the music, but Jamie is keen to clarify that the album isn’t intended solely as a wistful gaze into the unknown tomorrow.

“The whole futurism thing is certainly in danger now of being overstated,” he warns, “and the distinction to make is that to me it’s more of a sentiment than an actual description of future events. There’s a kind of emotional, imaginative place that we call futurism. I would call it romantic futurism.”

Conversely, the same cultural references of vintage sci-fi soundtracks have led to many a reviewer recalling fuzzy memories of watching Legend or Blade Runner for the first time, getting rather misty-eyed in their interpretation of the album. “One of the things that I’ve come up against is Severant being called nostalgic,” Jamie politely bemoans, “which I wouldn’t rally too hard against except for the fact that it wasn’t in any of my intentions when I was writing it. I’m much more interested in what’s going to happen tomorrow than what happened yesterday.”

Misinterpretations being what they may, Jamie can still see a valid catalyst behind the reaction, which further alludes to his notion of ‘romantic futurism’. “Perhaps one of the reasons why it seems to cross over into this feeling of nostalgia is because that kind of romantic futurism hasn’t been prevalent in cultural terms for the last 10 or 20 years,” he supposes. “It was last carrying a lot of weight in the ‘70s and ‘80s when a lot of new tech was flooding in and there was a new feeling for what the future might hold, alongside a new ability to describe that with video and digital technology.”

Something that does chime loud and clear throughout Severant is a feeling of duality. At many points, the drum machine beats take on a manic intensity, as shards of hats, toms, claps, snares and kicks dart around each other at surprisingly high BPMs. In the same instance the melodic content is slowly and smoothly spread out, revelling in the ample room in which it floats slovenly above the merry madness of the percussion below. The act of achieving two (or more) feelings simultaneously in music is not an easy task to master, but it was an end to which Jamie was actively heading when it came to making the album. What’s interesting is that the source of inspiration for such an effect came from trap rap, a tributary of hip-hop centred around MCs and producers such as Gucci Mane, Waka Flocka Flame and Lex Luger.

“I’m much more interested in what’s going to happen tomorrow than what happened yesterday”

“The rap stuff, even if it can feel light in content, actually has more meaning to it under the surface. What can come out seeming like violent, one-dimensional lyrical content has a lot more to it that you can’t quite hear when you first listen,” Jamie asserts, sticking up for a genre which attracts much criticism for its apparent glorification of drugs, guns and misogyny. “Clipse for example, boast of their really aspirational lifestyle, and then at the same time they’re expressing regret for how they got it and downplaying its meaning because they think it’s ethically wrong. Their lyrics run in different directions.”

This notion of split meaning in the music naturally crept into Jamie’s work ethic as the album came together, ultimately reflecting the complexity in life quite succinctly. “When I was writing tracks, I found myself having things running in different directions so it was not one-dimensionally happy or one-dimensionally sad. It can make things seem a bit more resonant for any music. Stuff that transpires in reality isn’t particularly one or two-dimensional at all.”

Aside from contemporary rap music and 80s sci-fi soundtracks, the other prominent musical reference point on the album is undoubtedly juke, the Chicago-born mutant offspring of ghetto house. With its unconventional rhythmic patterns and dizzying speed propelled by the dance battles it soundtracks, juke provided an ideal muse for Jamie’s romantic futurism.

“I think juke sounds hyper-modern,” beams Jamie. “That’s what I find really interesting about it; its invention in rhythm, and its peculiar intensity. There is a distinct headspace that comes out of it, and the patterns move between sometimes being fast and then becoming slow, while the samples are triggered in really odd ways. Everything about it feels alien and new.”

Neatly (and indirectly) encapsulating where the success of his own music lies, Jamie’s achievement is in rising above these myriad influences, and distilling them down into a complete and focused body of work that feels nothing if not unique. With such earnest intentions and a diligent attitude to his work, one can only dream where his music will head next.

Oli Warwick