Compassion Crew: Digger With Attitude

Dublin record “digger supreme” Compassion Crew tells Richard Brophy about the travels and stories behind his new compilation Compassion Cuts, Tapes & Acetates.

It’s a cold February night in Dublin. An icy wind is howling in from the river Liffey as this writer makes his way up through the narrow streets of Smithfield to meet with one of the great modern day diggers, Compassion Crew. On arrival at his cosy terraced house, Compassion Crew, who only wants Juno Plus use his first name, Robert, makes tea and proceeds to discuss his all-consuming passion. Responsible for releasing records on Rush Hour, Running Back and Major Problems as B.D.I and Compassion Crew, he is about to embark on a new chapter of his relationship with music, thanks to the release of a compilation, Compassion Cuts, Tapes & Acetates.

Consisting of ultra-rare music that spans decades, formats and continents, the compilation has been two years in the planning and is the result of his ability to seek out wonderful, obscure releases. “There are a lot of things I want to tick off and this is one of them. No one knows who I am and that gives me a lot of freedom. I’m a record collector and a part-time producer. I have a day job, so I can do whatever the fuck I want,” he explains.

Robert’s interest in electronic music spans three decades, beginning in Dublin during the mid-to-late-‘80s when he was a teenager. “I went to Sides, Asylum, UFO, Temple Of Sound, everywhere really,” he says, reeling off the names of the great Dublin clubs that were at the centre of the Irish capital’s electronic music explosion. “If you were in Dublin at the time, that’s where you went. I don’t think people realise it, but at this time, dance music in Ireland and the UK was pop music, it was mainstream. It was everywhere, so many people liked it,” he adds.

Nowadays, Dublin is a modern, outward-looking city, but back at the tail end of the ‘80s it was in the midst of a crippling recession, with many young people forced to find work in other countries. “Dublin was a lot rougher then, you wouldn’t have been walking down the docks in the ‘80s,” he says a propos of the route I took to get to his house, but adds “of all the clubs I have been to, I never saw trouble, that’s not the Dublin way. It’s more about the party – Irish people like to get high and have a good time.”

Nowadays, Dublin is a modern, outward-looking city, but back at the tail end of the ‘80s it was in the midst of a crippling recession, with many young people forced to find work in other countries. “Dublin was a lot rougher then, you wouldn’t have been walking down the docks in the ‘80s,” he says a propos of the route I took to get to his house, but adds “of all the clubs I have been to, I never saw trouble, that’s not the Dublin way. It’s more about the party – Irish people like to get high and have a good time.”

Apart from naked hedonism, those early days in Dublin clubs attuned Robert’s ears to the possibilities of just how odd and abstract electronic music could get without losing its audience. “I always remember going to a club like Temple of Sound and standing there going ‘what the fuck is this?’” For Robert, great dance music has to possess this factor. “It has to be a little bit weird and oddball. Hearing Felix da Housecat or the old Relief stuff on a great sound system, 60 per cent of the crowd were high, it was the perfect opportunity to throw out some weird shit and mess them up, that’s what they were paying their money for,” he says about the club known simply as ‘The Temple’.

Hearing great Dublin resident DJs like Billy Scurry or Liam Dollard play cutting edge house and techno week in week out made Robert curious about how these records actually came about. “You think, ‘maybe I can give it a go’. You are feeling your way around, you don’t really have the cash for the sampler or the drum machine. You are doing what you can do. A lot of the records you like are based on samples.” Robert freely admits he didn’t know much, “I wasn’t hooked up with a buddy who knew, I just pieced it together myself. You do things slowly, but you do it methodically, take your time and learn it,” he explains.

Eventually he did learn, but it was a long, slow process. Robert’s first records started to appear a decade later in 2005 as B.D.I., first on London label Fluid Ounce, then on local Dublin operation Scribble. By 2009, Robert had landed on Rush Hour with the anthemic “City & Industry”. “I started off working as B.D.I. then Compassion Crew and thought I might flip over to something else,” he explains, while observing wryly it was “a career killer not to follow up the record on Rush Hour with something. I was happy to take a couple of years to do that.”

In 2011, Robert released the more subdued Decoded Messages Of Life & Love on the Amsterdam label, but he had already moved on. Under a new alias, Compassion Crew, he put out the percussive house Paper Tears on Running Back, followed by the ravey Masters of the Gentlemanly Art for the Dublin label, Major Problems.

Through all of these twists and turns he was learning how to produce, Robert also found out about the source material that the great records he sought to emulate were based on. Discovering where samples came from and how they are used kick-started an interest in digging that has eventually led to the release of the compilation Compassion Cuts, Tapes & Acetates for Major Problems.

“Eventually, the penny dropped – ‘this is this house record I love, but here’s the sample’. Then I discovered this world of older music, beyond house and hip-hop, where the samples came from and that’s when I really started to dig.” Robert details the journey he took to become the digger he is today. “You just start with funk and BBE compilations and then you get into library music and gospel and then something deeper, the tape scenes. You get better at it and before you know it, you are into genres you haven’t heard before.”

Library music proved to be a particular revelation he says, “there is some absolute gold there – it was music for people making their own music for adverts.”

Library music is represented on Compassion Cuts, with the Roger Davy’s cosmic intro, “Brumes Sur Mars”, from his 1972 album, Patchwork Orchestra 5, as well as featuring Swiss composer Olivier Rogg’s brilliant cocktail bar meets ‘70s real estate ad soundtrack “GE CH”. However, Robert’s digging didn’t stop there. “If you go a step deeper, there is music at demo level, private press. People who sold it out of the boot of their cars, it never got proper distribution. Then with the tape scene they didn’t have distribution, they had mailing lists and sent them around, swapped them. There are some people who have collected all of these. I’m not talking about doing this over a couple of years, more over about a 10-year period,” he explains.

Our conversation started off with compilations and morphed into Robert travelling during holidays from his day job to Australia and America, as well as European countries to dig. He says he hasn’t been to South America yet, and despite his extensive travels, “it’s just a hobby, but a great hobby”.

So where was best city to hunt for music in?

“Tokyo was the big one,” he says without hesitation. “I got a copy of My Pops by Popsong’s Factory for 4 euro. It’s worth about 350 euro, but more importantly, it’s a dope record, drum machines and vocoder heaven, you can’t go wrong.” Robert goes on to detail his latest musical interest, “I’ve got big into gospel lately because when those guys are singing there is no commercial agenda – they actually believe in Jesus Christ, so its pure spiritual emotion. They aren’t in a studio trying to bang out a hit.”

Later on, he plays me one of his gospel finds and it’s hard to doubt the unnamed vocalist’s sincerity as he performs a slightly off kilter ode to the Almighty against a primal drum track. But back to digging; Robert says a lot of his journeys to far-flung locations were highly speculative. “It’s pot luck, just looking for stuff, but you pick up some nice pieces. I’m not here to fill walls, I just want to have a nice collection. Early days, pre-internet, I was somewhat limited as to what I could do, but once the internet kicked off 10-15 years ago, there was a whole world at my fingertips.”

One of the directions the internet led Robert into was the ‘80s tape scene, a largely undocumented, almost impossible to map out section of the electronic music ecosystem. “A lot of the guys in the tape scene were into early electronics and I am into that proto-house sound,” he says, explaining his fascination with ‘80s tapes. “There is such amazing music, but it is so rare. A lot of it I will never own on tape, it’s from friends who have rips. I have a huge want list of tapes, but you are unlikely to get an original copy. You are talking about 50 copies made in 1983 or 1984.”

This aspect of his digging habit has fed into his productions and he believes using samples from such rare source material gives his music an edge. “I sampled a tape for Masters of the Gentlemanly Art – no one knows the record has a sample, or really cares where you sampled from. They probably think I banged it out on a keyboard. The tape I sampled is so rare, I don’t know anybody with a copy. I got my rip from a guy in Scotland who had a guy make him a copy from the original in the late-‘80s and he is the only guy I know, a guy with a copy of a copy. The thing is, you can’t do this on your own. The thought of walking in somewhere and picking up all these tapes, it’s not going to happen. You do need friends who are specialists in certain areas. They can then hook you up. When you start digging that deep, you almost go too deep,” he concludes.

The fact there is no money involved in underground dance music means the concept of ‘cease and desist’ is redundant. However, in relation to the sample used on Masters of the Gentlemanly Art, Robert wanted to credit the producer and acknowledge his role in the record. “I managed to track the guy down. I didn’t clear the track, I only found him after it was out. He thought I was hitting him up to get an original copy of the tape, but he could hardly remember the tape or recording it, he had no masters, he had nothing. I am sure I will do a compilation and clear my conscience and license it properly.”

The fact there is no money involved in underground dance music means the concept of ‘cease and desist’ is redundant. However, in relation to the sample used on Masters of the Gentlemanly Art, Robert wanted to credit the producer and acknowledge his role in the record. “I managed to track the guy down. I didn’t clear the track, I only found him after it was out. He thought I was hitting him up to get an original copy of the tape, but he could hardly remember the tape or recording it, he had no masters, he had nothing. I am sure I will do a compilation and clear my conscience and license it properly.”

Another sample used on the Masters of the Gentlemanly Art release came from a 7” featuring a Scandinavian artist playing one of his sculptures in the open air. He proceeds to pull it out of his neatly packed shelves. Originally only available to purchase in art galleries, it has a price tag of approximately 2,000 euro. Coincidentally, he was taking delivery of it when he first got to know Dublin DJ Barry Redsetta, who runs the Major Problems label.

He is also quick to point out price or exclusivity should never get in the way of digging. “A lot of the records I own are 3 dollar records. They aren’t mainstream, they just aren’t known yet. There are a lot of guys out there digging, if you can get a great record for 3 dollars great, but I will also pay the money for the record if I have to.” He applies the exact same criteria, “if it’s a 500 dollar or 2 dollar record. If it’s got that feeling, I’ll buy it,” Robert explains.

Despite the occasional blurring of the lines between his production and digging, Robert claims there are some pieces of music he will never sample because they are “too perfect”. He says that in choosing samples, he looks for flaws and imperfections, whereas the tracks he considers to be perfect, he leaves untouched.

Showcasing his vision of musical perfection – and indirectly his advanced digging skills – led him to put together the Compassion Cuts, Tapes & Acetates compilation. Robert says he had kicked around the idea for the past ten years, and has a personal love of the compilation format. “I don’t write music, I sample other people’s work. I am never going to do an album myself, so a compilation is like an album to me. I love compilations, I was always fascinated by the idea of someone saying, ‘you know I have been doing this for twenty years and here are the 10 tracks I think are the best’.” To Robert, compilations remain a great way to develop your record collection.

The compilation has taken Major Problems down a different route from its usual house and techno releases. Apart from the above described library music, it features Ethiopian act Admas with a bizarre synth-led boogie amalgamation, the sprawling guitars and low-slung funk of Henry Hektik & Thomas W. Sutter’s “Infernal Jet Waltz” – culled from a limited edition cassette – Tetelestai’s cosmic rock “Prologue” as well as Plustwo’s ultra-rare Italo Disco “Fantasy” and Frak’s wonderful 1995 acid and piano keys house track “Uttoz Gives A Song”.

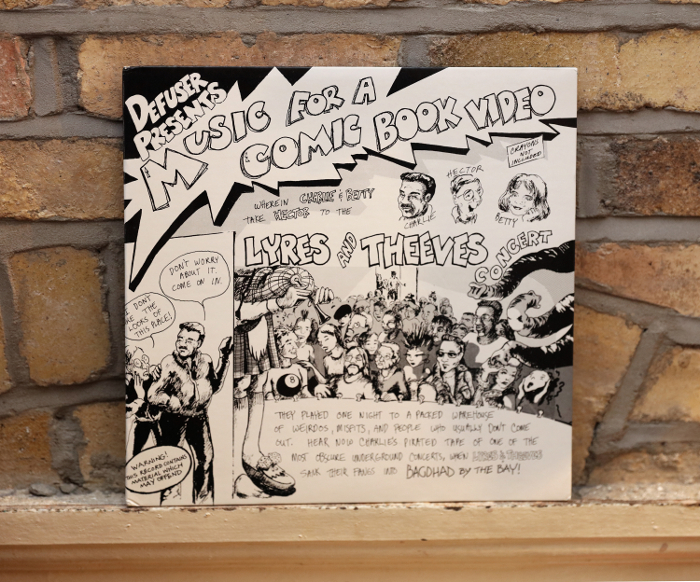

Bookended by some weird and wonderful interludes from long-forgotten acts like Defuser and Beatnik Love Affair, it’s one of the most lovingly, painstakingly curated compilations of recent years. Unsurprisingly, its origins are rooted in one of Robert’s regular digging trawls. “I came across this tape and there is a track on it, it is one of the best, most mind-blowing pieces of music I have ever heard. I started hunting the producer down and started putting the rest of the compilation together,” he explains.

“I got some joy with licenses for the other tracks, and developed a relatively decent relationship with the producer. By this stage, I had finished three-quarters of the compilation and was waiting back to hear from this first producer. Suddenly I got a reply though his manager saying ‘nah, he doesn’t want to do it’. He doesn’t want to give permission, he’s pulling it, he doesn’t want go back to that part of his production life. I was like ‘oh fuck’, that was the reason I started the whole thing.

“I don’t want to say who it is because the fight’s not over yet,” he says. “I want to work some magic here. Trying to sell this imaginary dream to him, that might be hard to understand, but when I send him over a copy with a nice little bottle of Irish whiskey and a thank you note, then let’s see, but that track has to be compiled.”

Apart from this rejection, Robert spent a lot of hours trying to track down up to 18 artists from his wish list and the goal was to secure 11 or 12 licences for the compilation. He says he received a lot of help along the way from the most unlikely sources – the owner of the Vinyl on Demand label, mastering engineer Thomas P Heckmann and random YouTube users who upload clips of rare material – and that “10 per cent of the stock will be gone just by me sending thank you gifts to all the people who helped.”

Despite this, the process was time-consuming. “I can understand why people do individual reissues or an LP, you just need one guy,” he says. To get 11 or 12, it took a couple of years to sort. Tracks dropped in and out. Because you are on the oddball end of things, all I can do is pitch the project as honestly as I could and once I hold it in my hands I hope they and I will see what I was trying to do.”

The other issue he faced was many of the artists he contacted had changed careers and were no longer making music. “Some guys who I contacted are now gynecologists or monks in Tibet, they are scattered all over the place. Half the guys we dealt with, they would say yes and after that, any correspondence has been low to none. They have moved on in their lives, they did one album.” He felt at times like he had to convince the artists it wasn’t a scam. “It would be like you writing a little essay in school when you were 14 or 15 and 30 years later somebody saying ‘this is amazing, can we use it in a short story compilation?’ You’d probably think, ‘these guys are scamming me, they are going to ask for my PayPal!’”

On other occasions, the requests went smoothly. He met one of the Admas brothers in a bar in Dublin who coincidentally happened to be touring in Ireland that week. “I met him for a drink, hooked him up with some free barbecue, a bottle of rum to bring back to his brothers in Ethiopia and we did the deal,” he says. Plustwo’s “Fantasy” was secured within 24 hours and Frak agreed after a few days, but didn’t want to accept any payment.

Once the licenses were in place, the remastering process involved sourcing the commercial releases because no master tapes existed. In some instances, the label had to get the tapes flown in from collectors in the States. “The amount of hours I put in has been insane, but it was really enjoyable and there is tonnes more music out there,” he says, hinting at a second volume. “What I want people to do is to listen to it from start to end, sit down with a cup of tea, a glass of wine and treat it as an album made by different musicians, from across the globe, across a couple of decades. If you do that, you can have a really nice experience,” Robert adds.

What about the argument that there is too much focus on older music and too many resources spent on reissues, and there is an inherent sense of snobbery at play simply because a piece of music is 30 years old and was only released in a limited edition format?

Robert gives a considered reply: “When you hear a magic track from 1984 and you know there were only three drum machines in the whole of Switzerland at the time and the guy made it in his mum’s shed before he even heard the first house record, I am listening to all of that and I am listening to the record, whereas if I thought someone threw out something mediocre on modern day equipment, it would lose me fast,” he says, adding quickly: “But don’t get me wrong, it’s gotta be a dope track, first and foremost. If you just got romanced by the fact it’s old and rare, it’ not going to work, it’s got to tick all the boxes. Plus you only have X amount of money to buy all of these records, so I’ll pit each record against the next. The best one I buy, the others go back into the pond for someone else to buy.”

It’s not surprise Robert is sceptical about the music media – this is his first interview he has done – and believes mainstream electronic music operates in the same way as pop music. “For Kylie Minogue’s manager, insert every A-list DJ’s manager, there’s no difference. It’s the same game- take the bookings, make the money, juice it for as much as you can. They (the media) want to champion a genre or a scene or a star so that they can all jump on the bandwagon. It has been dumbed down, but only if you go to the top three resources,” he says.

However, Robert says alternatives exist and YouTube has an amazing amount of material waiting to be discovered.

“You will open up a door and take a left hand turn here and a right hand turn there and 10 years later you are up to your eyes in weird tapes that you can’t believe anyone produced 30 years ago! I started with BBE comps, and developed my interest. My taste has stayed the same for the last 10-15 years, but my ability to source has become much better. It’s all out there, you just need to look.”

Interview by Richard Brophy

Compassion Cuts, Tapes & Acetates is out this week on Major Problems

Major Problems on Juno