Domestica: Authenticity, Creativity, Personality

Flora Pitrolo tracks down Domestica founder Jordi Serrano to discuss the Barcelona label’s development over the past five years and its distinctly DIY approach.

There are three things which have consistently made me smile about Domestica Records as it’s blossomed over the past few years. Firstly, there is the refreshing insistence on supporting the Spanish synth scene. Second, the curation of Domestica is clearly personal, discerning and considered. The label manages to bridge gaps between the romantics and the futurists, between angry goths, hysterical punks and dancers. Thirdly, the way the records look and feel; Dada-esque designs, hand-stamped materials, cut outs and silkscreen prints: good old fashioned craftsmanship. These three things chime well with the word domestica. Homemade, home-chosen, home-lived.

“Yes, the name of the label refers to a philosophy of work; to a way of doing things,” Domestica founder Jordi Serrano says. “When the first commercial synthesizers began to appear in the late 1970s,” Serrano continues, “people with less money or with no musical knowledge could begin to use them, and this changed the way we hear and make music, radically.” It’s this moment that informs Domestica, Serrano feels.

This attention to detail Serrano puts into the records he releases is clearly a trait of his, it’s something he wants for them, and it’s well planned. As we organise to talk one day in March, Serrano has labels to design, printing to finish, things to do. In between his tasks of single-handedly running one of the most interesting reissue projects around today, he’s comes across as personable, concerned about his English, about being late, about changing dates. We end up chatting online, in Spanish, over the course of few days in a kind of rolling conversation that’s hard to end, and with the many questions I have, Serrano has interesting, precise answers, some of which catch me off guard. I begin by surprising Serrano though, telling him it’ll soon be five years since the label’s debut release, Modern Art’s Circuit Lights.

“Coming up to five years, it’s true, I hadn’t thought about that,” he says. “But you know, it took two years, from the time I first spoke to (Modern Art founder) Gary Ramon, to the record being ready,” Serrano explains. “Domestica didn’t exist, so I couldn’t show Ramon anything – all I could communicate to him were my ideas, my energy, my enthusiasm, which via email isn’t easy,” he says. Seranno tells me half a year was spent in frustration at a mastering studio near Barcelona trying to perfect the Modern Art record, “I couldn’t find an audio engineer I liked,” he laments, and he remembers feeling disheartened at some of the mastering jobs he received. A chance meeting with Yves Roussel, Domestica’s sound engineer to this day, helped bring focus to the label he says. “By the time Modern Art came out, we were already working on various other projects.”

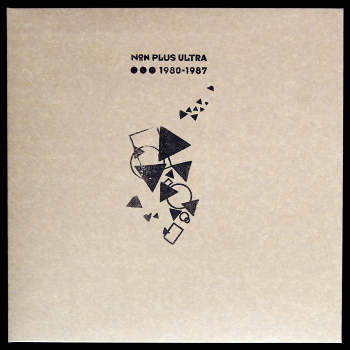

Many of those other projects have been great records – the brilliant Night-Moves and Dark Like a Restaurant singles, for example. Or the suave but rather lovely Red Violet Red reissue, the altogether glorious Moß Garten / Vildsvanen archive and not one but two additions to the S.M. Nurse canon. Yet the most crucial thing that Domestica has done is shine a light on its own domestic artists, drawing attention to the variety and to the richness of 1980s Spain. While the genius of people like Aviador Dro or Diseño Corbusier has been clear to international audiences for a long time, we have Serrano to thank for repressing veritable joys from groups and artists like Interacción, Kremlyn and Fernando Gallego, Funeraria Vergara and Vam Cyborg. Demos and other hard-to-find jewels from the aformentind and other artists have been carefully catalogued by Domestica, both in single records and the two Non Plus Ultra compilations, two monumental contributions Serrano has given the label.

“The first Non Plus Ultra was supposed to be our first record,” Serrano says. “Then it took so long to make, that it came out third, but I’m still very proud of it.” Serrano explains these compilations hold great sentimental value to him personally, while giving the label a conceptual edge. “It was a long, archeological process which I’ll always remember fondly,” he recalls. “As an archive of seemingly forgotten bands from our peninsula, I think it was totally necessary to do, but Non Plus Ultra was also a way of exhibiting what Domestica Records was going to be, not only musically but more generally, from an aesthetic point of view.”

So does the music on Domestica share a common thread, indeed from a more general, aesthetic point of view? Or is it something about a certain Spanish approach to synth music? There’s something about the sound of Domestica’s artists that I’m eager to learn more about. I reel off a list of the traits – a certain humour, a certain roughness, a certain insanity – that I feel appear on the label consistntley throughout its output, and thankfully Serrano is in the mood to indulge. “Getting your hands on, say, a Kraftwerk, Heaven 17, OMD record was difficult,” Serrano explains of the early 1980s in Spain. “There were hardly any radio shows playing electronic music and the local scenes weren’t really connected, which could also be a good thing, depending on how you see it,” he says.

So does the music on Domestica share a common thread, indeed from a more general, aesthetic point of view? Or is it something about a certain Spanish approach to synth music? There’s something about the sound of Domestica’s artists that I’m eager to learn more about. I reel off a list of the traits – a certain humour, a certain roughness, a certain insanity – that I feel appear on the label consistntley throughout its output, and thankfully Serrano is in the mood to indulge. “Getting your hands on, say, a Kraftwerk, Heaven 17, OMD record was difficult,” Serrano explains of the early 1980s in Spain. “There were hardly any radio shows playing electronic music and the local scenes weren’t really connected, which could also be a good thing, depending on how you see it,” he says.

We talk primitive electronics, the development of local scenes, the fall of Franco’s dictatorship in 1975 and what that meant in terms of lag – and subsequent acceleration – of Spain’s youth subcultures. “My sense is that in Spain distribution in those years was very limited – musicians who were interested in this kind of sound didn’t have a lot of references,” Serrano believes. “So when these musicians began to experiment with synthesizers every-thing had to be invented, which, summed with the ‘new’ feeling of freedom given by the fall of Francoism, meant that they really had a white page to write on, with hardly any influences,” he says. Serrano explains these trailblazing musicians as “explorers” who did things their own way for the first time, and he feels, “they felt free to follow whatever path they wished to follow, and so the sound is genuine, and each group develops it own sound very personally.”

Serrano, a trained visual artist and graphic designer, essentially runs Domestica by himself, while doing as much as he can in the studio, and with local typographers, to follow each release’s journey every step of the way. It emerges clearly that a lot of energy goes into preserving Domestica’s ethos of creating something small, home-made and unique, with everything sounding and looking just right. Serrano studied design in order to start a record label and he’s since developed a maniacal, some might even say fetishistic, attitude to applying attention to detail on top of an earnest economy of care. “I think of a record as of an object in its entirety, and the packaging has to chime in tune with its content,” he beleives. “I like to work manually, so that every piece has its own value and so that the mentality that engendered the music is preserved,” he says. “We never do more than 500 editions of a record, so it would be a shame to miss an opportunity to make it really special. If it can be done, then it should.”

Because the past doesn’t seem as ‘usable’ as it can sometimes feel on the reissue market, and because Domestica’s musical endevours have ventured into the present, the appreciation Serrano shows in what he’s doing feels fresh. Domestica clearly loves and respects much about Spain in late ‘70s and early ‘80s, which carries quite seamlessly into present endeavours, regardless of whether Bandcamp has substituted mail-art. When I ask him about Stathis Leontiadis, aka Doric, whose LP will be released by Domestica in May, it’s precisely this punk approach which sparks Serrano’s enthusiasm. He speaks of Doric’s ex-band, Human Puppets, quickly becoming one of his favourite new bands the first time he heard them. “I love the philosophy of this band, this DIY, punk mentality which is so clearly reflected in the music they make,” he says. “They have clear principles about the kind of sound they want, and they’ve kept working on these ideas for many years.” He adds, “that’s why I think Doric will become a cult act, in time.”

Serrano tells me he searches for “an extreme sense of creativity, authenticity,” in people’s personalities. Are these traits getting rarer and rarer? “Every now and again, they appear”, he assures, “although it’s hard work to find them”. Serrano admits he dedicates more time to the past because he knows it better than the present, explaining “I have a feeling that 30 or 35 years ago, more projects used to start with a wish to move away from conventionality and imitation.”

“We never do more than 500 editions of a record, so it would be a shame to miss an opportunity to make it really special. If it can be done, then it should.”

“Maybe it happens just as much these days, but I find it hard to identify what those projects are,” he says. The feeling of knowing the past better than the present is the odd double-bind of the reissue scene; this love for the future seen from the past can leave a strange sense of loneliness in the contemporary. While this twang of melancholy certainly emerges from my time with Serrano, we don’t indulge. I ask him about the two compilations released in 2012 and 2014 from the monthly Transmission party. “It was really the only regular party in Barcelona dedicated to electronic, coldwave and industrial music,” Serrano explains. “So although we left the selection of the tracks to the organisers, we wanted to help get them out, because they document a current thriving international scene, and because some of the bands that played there deserve more exposure.” Serrano also closely follows John Talabot’s Hivern Discs label, also Barcelona-based, which he declares, “is doing marvellous work.” And while the present may not be his speciality, he acknowledges “it seems like every day there are new bands, and a lot of them which surprise me and do interesting things.” Serrano adds, “at the moment I’m quite taken by a debut record by Chicago-based duo Valis, The Demolished Man, out on DKA Records in Atlanta.”

Towards the beginning of our conversation, as I was asking him whether Domestica had come out of a particular scene, Serrano had spoken of his local loneliness and his intended global reach. “Of course it’s great to organise events and to have people meeting each other, but trying to sell vinyl is a different matter,” he says. “You can’t only think about the local.” The idea for Domestica – like many of its sisters, reissuing wonderful lost records around the world – stems from what Serrano refers to as the “virtual boom” of 2005/2006, when a lot of the material we have the luxury to hear on vinyl these days began to circulate on blogs as downloads. “My ex-collaborator started to frequent very exclusive collectors’z circuits,” tells Serrano. “We started listening to a lot digital archives of things we could have never heard otherwise.”

“I kept all this stuff and started filtering it according to my taste, and towards what would have become the label,” Serrano explains. I was shocked to hear Serrano has only been listening to the kind of music he puts out for about ten years, having spent most of his life investigating sounds from the ‘60s and ‘70s. “I used to listen to long melodies, to dreamy soundscapes, or to academic music, for intellectuals,” he says. “It took me a long time to get into the 1980s, I was a bit scared somehow, maybe I knew I’d never come back!” Serrano adds. “My palette of sounds suddenly widened; now the music was much more danceable, much more experimental, self-produced, made in complete independence, the field became huge,” he says, “Endless!”

“I kept all this stuff and started filtering it according to my taste, and towards what would have become the label,” Serrano explains. I was shocked to hear Serrano has only been listening to the kind of music he puts out for about ten years, having spent most of his life investigating sounds from the ‘60s and ‘70s. “I used to listen to long melodies, to dreamy soundscapes, or to academic music, for intellectuals,” he says. “It took me a long time to get into the 1980s, I was a bit scared somehow, maybe I knew I’d never come back!” Serrano adds. “My palette of sounds suddenly widened; now the music was much more danceable, much more experimental, self-produced, made in complete independence, the field became huge,” he says, “Endless!”

Serrano’s relatively fresh ears, or ears cultivated elsewhere, are evidently – political, socio-cultural, philosophical conversations aside – at the root of Domestica’s sonic identity, one that strikes me as very distinct, although I suspect he himself can’t hear it, or separate it from his taste. It has to do with atmosphere more than it has to do with sound; bleepy and playful, clangy and epic, or dusty and mournful, Domestica’s catalogue has a common thread which is more feeling than genre-bound. As Serrano explains, he likes “things that move between registers, things which incorporate various colours even though there’s an element keeping those colours together.”

Domestica are about to reissue a legendary feat in the art of moving between fields, the highly celebrated Pas De Deux compilation, originally released on Diseño Corbusier’s own Auxilio de Cientos in 1985. It’s one of those glorious, schizophrenic compilations you’d expect from Insane Music, Trax or EE Tapes, that offers an expression of a happily unleashed and unhinged creative euphoria. Serrano speaks of Diseño Corbusier’s Ani Zinc and Javier Marin’s work as inspirational to his own. “If you think of Granada in 1985, without internet and with hardly any money, they did something which hardly anyone in Spain did, and very few could have,” Serrano says. “They made people hear acts who were completely unknown in Spain and completely innovative, and really, it was quite risky.” He adds, “As the years went by, their work wasn’t forgotten – the exact opposite.” Original recordings were provided thanks to some inestimable input from Javier Marin and have been fully restored, “I think it will sound really very good,” Serrano states excitedly.

This Pas De Deux reissue may well turn out to be as influential on the international market as the Transmission and Non Plus Ultra compilations have been for the Spanish scene. All of the bands featured on Pas De Deux have a very similar approach to Diseño Corbusier in terms of self-production, distribution, and aesthetics. The concept of Pas De Deux was to compile international bands formed by a couple, a boy and a girl. It’s heteronormative, but quite romantic, and music by Bene Gesserit, Cheiron, Influenza Prods., Deux Pingouins, Enhänta Bödlar, is all beautifully remastered for our joy.

As Serrano rushes towards a nightshift of 10’’ label design, I ask him how far he’s gone in order to track down an artist. He shares with me a story of trips to fruit-stalls in a Badalona market and phonecalls to dance schools searching for Kremlyn’s founding member J.J. Ibáñez “I thought I had nothing to lose, so I just rang and I was lucky,” Serrano says. “It was a wonderful feeling”. I query if the frontwoman of Kremlyn, Montse Berman, did anything else later in life. Serrano tells me “she sings with her friends, for the pleasure of doing it, and apparently she does it very very well.”

Without trips to fruit markets, early morning label designs, and all the other hard work, many of the personalised records Domestica have reissued and repackaged with love could well slip through the archives forever – as many do. Serrano explains as we gather our conclusive thoughts, “the records we put out could be the only chance a band gets to have their tracks pressed onto a record and heard,” and, he says, “my responsibility is to make the record as well as possible, or as well as I possibly can.”

Interview by Flora Pitrolo