Reel By Real: Entering The Surkit Chamber

It was 1991 when a young man known as Martin Bonds, born and raised in Detroit- who had recently dropped out of college where he was studying electrical engineering – found himself living in Juan Atkins’ Metroplex Studios. Here he helped out with engineering duties of a different kind – in sound. It wasn’t long before Kevin Saunderson had invited him to be a fully fledged engineer in training at his KMS Studios, part of the same building complex that was at the centre of Detroit’s techno scene. During this time he wrote and produced a record still talked about in hushed tones by those in the know – Surkit.

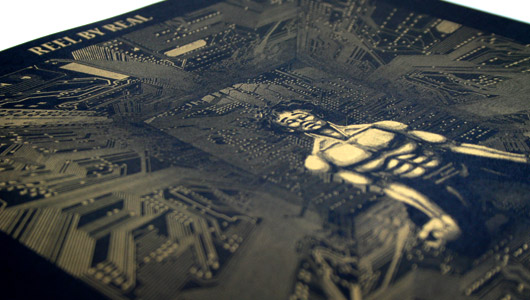

It would take Bonds twenty years to follow that record up, with his debut album Surkit Chamber – The Melding, an album whose title paid obvious tribute to his early years while remaining just as vital. It wasn’t until the release of that album in 2011 that I was made aware of Bonds, when this album appeared on my desk. It was difficult to know how to approach it, with artwork depicting a scene that could have been lifted out of William Gibson’s Neuromancer, with music contained within that sounded like Detroit techno that had just come out of a decades old time capsule. In a current musical climate filled with producers who go to great pains to authentically recreate classic sounds, listening to Surkit Chamber’s genuine approach to techno – raw, larger than life and filled with a feeling that you simply don’t hear that much any more – was an experience akin to having my ears syringed. As I began to delve into the history of Bonds it became clear that he was one of Detroit’s unsung heroes, and after a bit of legwork involving calling in favours from what I can only describe as Detroit’s own version of the “old boys network”, I was able to track Bonds down and arrange a Skype chat with him, in order to hear his story first hand.

When we speak, the friendly, affable Bonds is in good spirits. It’s only a few days after Detroit’s annual Movement Festival, which he used as an opportunity to meet up with a few old friends. “I went to a KMS 25 Years of Techno reunion, it was an afterparty for the Detroit Electronic Music festival, so I saw everyone that was part of the family – Kevin, Juan, Derrick, Carl Craig, y’know, and (Anthony) Shake Shakir, who I talk to quite a bit because he’s not far from where I live.” So how did he find himself becoming part of this family, and living and working in the studio complex that was arguably the source of much of Detroit’s best techno output. “There was no choice!” Bonds exclaims. “When I originally started with electronic music I was in the seventh grade, in 1977 or 78, ever since I heard Kraftwerk on a local station here in Detroit in 1977 and wondered how they got their sound”. In the years that followed he would listen to Parliament Funkadelic, New Order, Depeche Mode, Talking Heads, Devo, The Brothers Johnson, XTC, and a host Italian imports that would prove to be an influence. Later he would visit Chez Damier’s legendary Detroit club The Music Institute, where he was able to listen to these sounds and others like it on an underground club sound system for the first time. Meanwhile, he bought his first studio equipment – a Korg SuperDrums, a Casio CZ1000 and a Yamaha QX21 sequencer, and he made tracks in his bedroom with some guidance from his older brother Brian Bonds, who would himself go on to release records himself on ‘Shake’ Shakir’s Frictional Recordings as part of the trio known as Strand. “He was always into DJing, and he introduced me to Juan – he told me I should put some of the stuff I’d made onto cassette and give it to him. The next thing Juan heard one of the tracks I’d made and said ‘I want to use this, so get your gear, bring it down to Metroplex studios and lay the tracks down”.

It was through Bonds’ obvious talent for tape splicing and working with reel to reel machines, a firm friendship that had been struck up with Atkins as well as the financial limitations of Metroplex that led to him taking on the role of unpaid engineer in Atkins’ studio. But it was when he moved to Saunderson’s KMS Studios that he began to get paid for his work, training under Chris Andrews Mike Iacopelli, who had done recording work with Aretha Franklin and Stevie Wonder. Around this time Bonds found himself going on tour with Saunderson’s Inner City, where he found himself a reluctant performer. “I never intended it to be this way, but I ended up on the stage because a lot of stuff was looped in a sampler – background vocals – so I had to be on stage, and part of the act. I never intended it to be that way though, I wanted to scoot off to the side of the stage, behind the curtain, and Kevin was like “no no no – we gotta make sure we can make eye contact!”

However, it was his music from this period that would ultimately put his stamp on musical history. Adopting the name Reel By Real (which he tells me he got from the name of a track on XTC’s 1979 album Drums & Wires) he released his first record, Aftermath, in 1990. Its delicate, melody soaked arpeggio and deep, classically searching strings would come to form the template for his future work. Released through Virgin subsidiary 10 Records, it found itself on a compilation called Techno 2: The Next Generation, alongside early tracks from Carl Craig, Marc Kinchen and Atkins’ Infiniti alias. But it was Surkit, released on Metroplex subsidiary Interface Records, that was to go down in legend. But Bonds admits that he barely noticed any fever around it at the time, only realising its significance on the scene a few years later. “I actually didn’t pay much attention to it until years later, and then I noticed a few places that had the white label for sale for 500 bucks – I was like ‘what’? Most of the copies I see are white labels – I haven’t seen too many label copies”. But despite this, Bonds’ place in the city’s techno scene was by now firmly entrenched in its foundations – Atkins and Shakir both contributed to tracks on the EP, while his music was openly accepted by his peers. “I remember Mayday (Derrick May) playing my first single “Aftermath” via 1/4″ reel to reel tape at the club” he tells me.

After this however, Bonds seemed to disappear, and the reasons for this were the simple. “I ended up getting married and getting a job with the local government, working for the city. Four years later we had a kid and then another kid – it eats up your time a little bit”. In 2008 however, “Surkit” was uploaded to YouTube by a man named Leon Sewell, something that was eventually brought to the attention of Bonds. “My brother happened to tell me that someone had put it on YouTube” Bonds explains. The track had been sampled by drum & bass producer LTJ Bukem on his 1993 production “Atlantis” – something that was discussed in the comments, with “Surkit” being wrongly attributed to Bukem. “I noticed people were making comments about it, they didn’t know that someone else sampled the syncopated riff – a lot of people were surprised that it came from me”. The uploading of the track however proved to be a turning point for Bonds. “I kind of went off from there – it got me back into making tracks”.

Around this time Bonds had a flurry of interest from various labels interested in re-releasing “Surkit”, but it was Mojuba Records, run by Detroit techno enthusiast Thomas Wendel – otherwise known as Don Williams – that Bonds struck up a rapport with. “A few other people had enquired about licensing the track, but Don Willimas at Mojuba really seemed enthusiastic about it” Bonds explains with an obvious respect. The product of the union was two EPs, containing the legendary “Surkit”, “Distance” and “Serene”, as well as “Vessel In Distress” (produced with Juan Atkins) and “Sundog” (produced with Shakir). But despite Bonds’ role as a sound engineer, the original masters were not in his possession, and the painstaking work, undertaken by producer Redshape, had to be done from an original vinyl copy, sourced by Mojuba. The quality was obviously beyond Bonds expectations: “I tell you this, those guys are really good at engineering and restoration. Going from tape to tape to tape, there was a lot of hiss and noise on the original record – they did a great job.”

However, as well as the reissues, Mojuba were also making plans to release new material from Bonds after further conversations in which he revealed he had been steadily working on material for several years. All were new tracks made in the period that followed the uploading of “Surkit” to YouTube with the exception of “WRX” which Bonds tells me was also restored. But rather than the stacks of outboard gear piled up in Metroplex Studios, Surkit Chamber – The Melding was produced in the more inauspicious surroundings of Bonds’ own home, with Cubase 6, some plug-ins and a Dave Smith Mopho being the one concession to analogue technology. But it’s not something that Bonds sees as a problem, as he explains. “A lot of people are against plugins, and I was one of those people – I used to think like that, but I was a fool for years, I should have jumped on this a long time ago”.

When it came to the artwork for both the 20 Years Surkit compilation and Surkit Chamber, Bonds called on his old friend Abdul Haqq, whose Third Earth Visual Arts was responsible for the artwork on several Underground Resistance and Transmat releases, and lived in Metroplex Studios at the same time as Bonds in the 90s. “Abdul would hear something we were working on, come upstairs from his art studio and say ‘I like that, what’s the name of that’ – we’d tell him and he’d go back in the basement and come up with some ideas – it worked out great”. The striking artwork depicts a cyberpunk scene with a man-machine plugged directly into chamber with circuits adorning the walls. Given the album’s name and the image, featuring a tortured individual at one with technology, it’s tempting to see both as a reflection of Bonds own experiences making the tracks, and its something that Bonds agrees with to an extent. But rather than my own interpretation, which saw the cover as an admission of the difficult nature of the creation of the tracks, the cover concept came from an altogether more optimistic angle. “I gave Abdul the idea of electronic music with a soul, with some feeling – and that was his response”. Perhaps more crucially, it connects Bonds music with the rich lineage of optimistic sci-fi imagery that has been central to so muchDetroit techno since the very beginning. “It had that feel of a lot of the artwork that was done for Transmat,” Bonds says proudly, “I was really amazed when I saw it”.

I ask Bonds if he had the idea of “music with a soul” in his head when he was writing the tracks, and it’s clear from his response that though it may not be conscious, it’s clearly a guiding motivator. “I won’t say that was at the forefront – I think it just happens if you work on a bunch of tracks and a lot of them get scrapped, and usually the reason is something feels too stiff, or there’s not enough feeling in it. But I’ve always been like that”. This “soul” has been present in his work from the beginning, but on Surkit Chamber it only seems to come loaded with added significance given his time off the radar. I ask if he has the dancefloor in mind when he produces, given his distance from such concerns these days, and it’s clear that although not an intentional influence it’s something he can’t quite escape. “I never start a song with the idea of making a club track but then almost everyone in my musical family are DJs – so the dance thing is in the back of my head as the song progresses”. Although Bonds is keen to downplay the intention to make tracks that work on the floor, there’s an undisputed skill on display in the searing bass squelch of “Switchback”, the arpeggiated funk of “Buckshot” and icy electro minimalism of “WRX” that always counterbalances the deeper elements of his sound.

But perhaps more important than soul to Bonds is his political stance. Tracks like “I Won’t Follow”, with its repeated vocal mantra, and “Freedom From Want”, which samples Franklin D Roosevelt’s 1941 “Four Freedoms” speech, in which he addressed the fundamental freedoms that everyone should share, place Bonds’ work within the lineage of politically charged Detroit techno. Far from paying lip service however, it’s something that Bonds, who has worked for Detroit’s local government for the better part of two decades, feels particularly strongly about. “It’s definitely a statement that’s for sure. I don’t how you can not stand for something, or have an opinion, especially in these times in this country.” I ask him specifically what kind of messages he’s trying to use his music as a conduit for. “The message is not necessarily just tied to Detroit, because it’s more of a demographic kind of a thing. It encompasses the Western world. The influence I had was organised labour and unions, and the things that they’ve given us, as opposed to the old Reaganomics and the theory of the bad side of economics, where you give breaks to the so called job creators and the people that already have money – the idea being that in turn that money will trickle down to the rest of the population, which hasn’t been working for 35 years. You’ve got to stand up and say something sometimes if things are going to change”. I ask Bonds how much Detroit has changed in the last 20 years, and his answer is audibly weighed down with sadness and frustration. “The population has decreased probably by a good 20-30 per cent, there’s a lot more blight. It’s a lot more depressing, and because I work out in the field, I see it every day. But like they say, things go in cycles so I’m optimistic of some type of a comeback”. The overt politics embedded within Bonds music is refreshing, and he doesn’t worry about the possibility of alienating his listeners. “If selling records was my only source of income, then I may be a bit more timid about it, and try to be more subtle with it – but fuck it, if it isolates me or whatever, I’m still gonna do stuff I love to do when it comes to music”.

Twenty years is a long time for anyone to take to deliver their debut album, and questioning turns to just why it took him so long to follow up those early releases. “Well, I never really stopped, but I never finished anything, I just get an idea in my head and go work on something, but I’d never do anything with it, and it would just sit on the hard drive – I just became inactive when it came to releasing stuff”. There’s a sense that Bonds feels he’s let himself down, as he explains. “There were many occasions when I was younger and working in the studio at 3 or 4 in the morning, and Juan would walk in when I was in the middle of a track and I wouldn’t know he was sitting right behind me. I’d turn around and what would come out of Juan’s mouth was ‘Did you record it? Did you record it?’ Cos I was just sitting at the console, muting things in and out and practising mixing down a track’ and Juan would say ‘Always record, because you may not be able to make another pass like that again’. Juan always told me to do that, and I should have paid attention to it, and I do kind of regret not doing it, because there’s a lot of material that has gone out with the hard drive in the garbage”. So does this regret at not creating more material stretch to missing out on a potential DJ career? “Not with a family no – if I was in a different situation where if I was a single guy and I was just doing this exclusively for a living I’d probably regret it, not being more active, not releasing more things, but that really hasn’t bothered me”.

Twenty years is a long time for anyone to take to deliver their debut album, and questioning turns to just why it took him so long to follow up those early releases. “Well, I never really stopped, but I never finished anything, I just get an idea in my head and go work on something, but I’d never do anything with it, and it would just sit on the hard drive – I just became inactive when it came to releasing stuff”. There’s a sense that Bonds feels he’s let himself down, as he explains. “There were many occasions when I was younger and working in the studio at 3 or 4 in the morning, and Juan would walk in when I was in the middle of a track and I wouldn’t know he was sitting right behind me. I’d turn around and what would come out of Juan’s mouth was ‘Did you record it? Did you record it?’ Cos I was just sitting at the console, muting things in and out and practising mixing down a track’ and Juan would say ‘Always record, because you may not be able to make another pass like that again’. Juan always told me to do that, and I should have paid attention to it, and I do kind of regret not doing it, because there’s a lot of material that has gone out with the hard drive in the garbage”. So does this regret at not creating more material stretch to missing out on a potential DJ career? “Not with a family no – if I was in a different situation where if I was a single guy and I was just doing this exclusively for a living I’d probably regret it, not being more active, not releasing more things, but that really hasn’t bothered me”.

Despite this, the release of Surkit Chamber has seen Bonds play recent sets at the Berghain which he says, humbly, that he “enjoyed quite a bit”, and a homecoming of sorts in Detroit at Metroplex last November. I ask if it’s something he’d like to continue. “Once a month would be plenty if I could get it”, he tells me, not particularly enamoured with the idea of regularly travelling long distances. Although he downplays the possibility of future gigs there’s an obvious sense of wonder in the way he describes the acoustics of the Berghain to me that show that his enthusiasm for the club, and most importantly for good sound remains undiminished. I ask him about the possibility of future releases. “Like I said, I loved dealing with Mojuba, and just a couple of months ago Don was asking if I had anything to send him for an EP which I hope to have done before July”. As well as this, he mentions tentative plans to collaborate with his brother, and most excitingly, that Shakir has asked to produce some material with him as well. It may have taken 20 years, but it looks like Bonds’ career as a producer is now well under way.

Scott Wilson