Keeping it raw: John Heckle

There’s been an analogue rumbling emanating from the north of England of late, with its ruminations reaching as far as Chicago before rippling back across the rest of the world. In terms of electronic music, Liverpool doesn’t have the same steady stream of artists that neighbouring Manchester or more southern cities have. Legendary club nights such as Voodoo still remain a part of 90s techno folklore, but the scene has tended to draft in its talent from elsewhere instead of nurturing locals, leaving the ‘Pool somewhat under-represented.

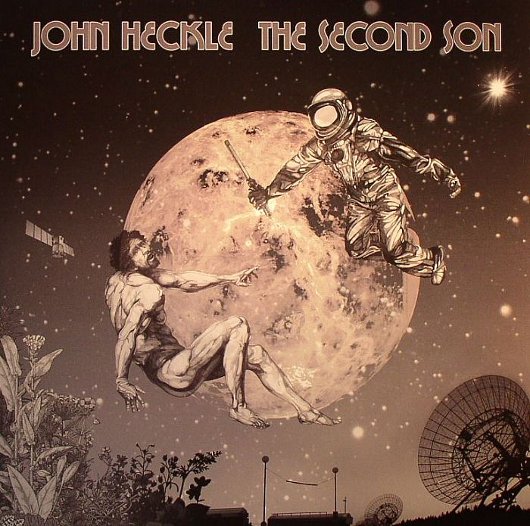

Things may be ready to turn, however, with John Heckle cementing his burgeoning reputation with the release of his debut album, The Second Son. John has shot onto the radar of many keen-eared house and techno followers in the past twelve months, largely thanks to his releases on Jamal Moss’ highly esteemed Mathematics imprint. Much like the rest of the output on that label, John’s music is deeply rooted in the sounds of 80s Chicago, but in the same way that Moss’ Hieroglyphic Being project takes those principles and contorts them, so too John’s tracks shudder and shimmer with ideas far beyond simple throwback records.

“There’s never any real method when I’m in the studio,” John admits, shrugging off any notion of consciously trying to offer a new perspective on familiar sounds. “I’ll just play until I think it sounds good. In terms of bringing something new to the table, using a mixture of classic analogue gear and new digital hardware certainly helps.”

The way the tracks growl and groan on The Second Son, it’s hard to imagine that digital production entered the equation at all, but John is convinced that the limitations of analogue equipment will rarely result in more than re-hashed old-skool sounds.

“I think a lot of producers who are making this revivalist music are only using the same gear that was being used in the 80’s,” John says. “Don’t get me wrong, this is no bad thing. This tends to be the gear that sounds the fattest and warmest, but by using new equipment with the same DIY ethos associated with the classic gear, producers can put their own stamp on their records and enable their sound to stand out.”

That said, there’s no denying that a great deal of the charm that John’s music possesses comes from the rugged finish he manages to leave his tracks with. While the digital aspect of his production may provide more scope for crafty editing and touches of sound design, it’s undeniably the imperfections of the hardware that glues everything together.

“I’m self taught in production, so everything has that gritty feel to it,” says John when asked about the hi-hat hiss and bassline fuzz he manages to imbue in his music. “I don’t know much about how to make everything sound nice and clean. Even so, if I was schooled in production I wouldn’t want it to sound any other way. It has to sound raw.”

As well as production values, that “raw” feeling John is pursuing comes across in the musicality of his tracks as well. Listening to the interplaying synth lines on his breakthrough release “Life On Titan” or the expressive keys draped over “What Once Was”, it would be hard to imagine achieving that feeling with software sequenced notes.

“I use one of the recent Juno workstation keyboards to sequence external gear and to record live playing,” John explains about his approach to improvisation in the studio. “That means no computer screen is necessary until I want to record a live take into the line-in, just so I can capture the audio. I’m enjoying leaving the computer completely out of the music production and mixing process.”

In something of a stark contrast, the digital-only techno of John’s earliest releases came out under the Hek moniker back in 2006, including a vinyl appearance on RSB records with a remix from British techno stalwart Female. Looking back on those more crisp, minimal excursions now, John is philosophical about the way they relate to his current output. “The Hek stuff was all software based,” he reveals. “I don’t think that using software was really playing to my strengths when I was making those tracks, but its still cool to listen back on them every now and then.”

In terms of influence, one listen to The Second Son and you’d be forgiven for thinking that John was raised on a steady diet of EBM, boogie, early house music and Detroit techno, so infused is his music with the atmosphere and experimentalism of those early forms of mass-produced electronic music. However, it took John until his teens to start listening to any form of machine beats (“I grew up listening to The Beatles and other bands mostly,” he admits). Now though, it’s the early pioneers of sonic experimentation that flick his switch more readily than any of his contemporaries.

“It’s hard to keep track of a lot of new music,” John says. “It’s always the music from decades ago which gets me excited. Just today I discovered an artist I had not previously heard of called Tom Dissevelt. I’ve been sitting listening to his music now for hours. It’s really mind-blowing electronic music from the 50’s and 60’s. Its almost unbelievable how much more inspiring, interesting and innovative that music sounds compared to contemporary music made half a century later.”

Be that as it may, John’s album has highlighted his own penchant for challenging sounds not bound by the conventions of dance music. The majority of tracks may thump away on a grinding 4/4 beat, but the monolithic drones of “Nothing Lasts Forever” in particular dart out into the unknown with the same exploratory attitude as Dissevelt or similar pioneers in sound. The question is, would John ever consider developing these ideas into fuller projects, rather than acting as interludes between the bangers on an album? “I guess I could do in the future, yeah,” John poses. “It’s all about being in the right mood when it comes to making tracks like that I suppose.”

Much like his attitude to other aspects of his music, John’s lack of pretension when pressed on this topic is reassurance enough that he’ll maintain his own unique path through electronic music without succumbing to trend or hype. In a world full of ‘high-art this’ and ‘conceptual that’, honest dance music coming from the heart just can’t be beaten.

Oli Warwick

Main picture credit: Andrew Ingram