A secret history of UK dance – how black Brit funk shaped the acid revolution

Bands like Light of the World and funk all dayers formed the DNA of British dance music

The seeds of Britain’s ongoing love affair with dance music were not sown in the ecstasy-fuelled “second summer of love” in 1988, but rather a decade earlier in a network of nightclubs, former ballrooms and vintage dance halls scattered across the country. Spearheaded by a handful of high-profile DJs – the forerunners of the ‘superstar DJs’ of the 1990s – this scene was responsible for effectively defining the blueprint for UK dance music culture and providing the ingredients for it to grow exponentially in the decades ahead.

These essential elements – British dance music’s DNA, if you will – included undeniably black musical roots, multi-racial crowds, significant regional variations, pirate radio stations, residential weekenders at coastal resorts and the UK’s first dedicated day-long dance music festival: a 12,000-capacity jamboree at Knebworth in May 1980 that mixed live performances and DJ sets from both the ‘Funk Mafia’ DJs (the dominant DJ collective in the South East, whose members included Chris Hill, Froggy, Robbie Vincent and Greg Edwards) and their rivals from the North and Midlands, amongst them Northern Soul’s most storied DJ, Colin Curtis.

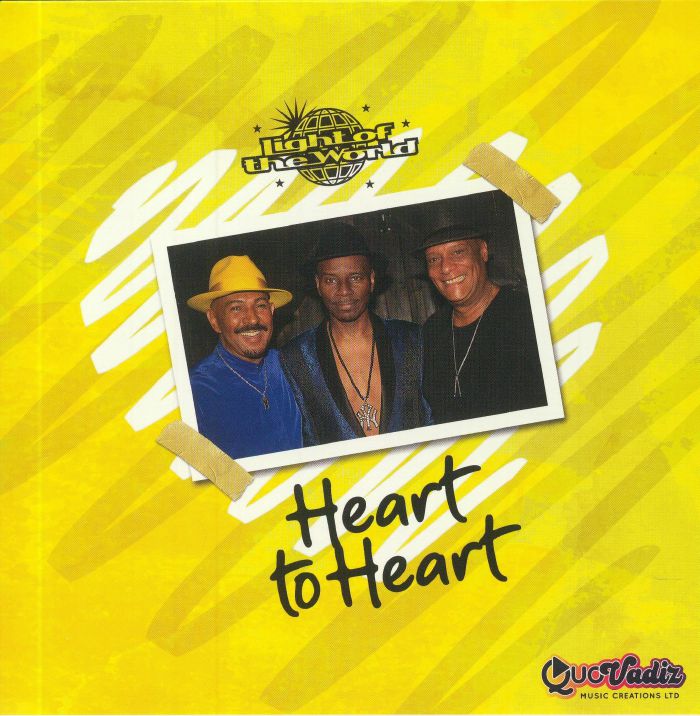

Fittingly, the headline attraction that day was Light of the World, a band who for the previous four years had spearheaded a style of music that for the first-time added a uniquely UK-centric twist to black American dance music, and jazz-funk in particular: Brit-Funk.

To the untrained ear, the earliest Brit-Funk records do not perhaps seem all that revolutionary, certainly in comparison to the hard, energetic and sub-heavy styles of British dance music that began developing at the tail end of the 1980s (think Bleep & Bass, breakbeat hardcore and jungle in particular). Brit-funk was unashamedly rooted in jazz-funk, modern soul and disco – and later incorporated elements from the emergent sounds of hip-hop and electrofunk – and many of the sound’s most celebrated bands, most notably Hi-Tension, Central Line, Beggar & Co, Linx and, of course, Light of the World, were initially inspired by a desire to replicate what they heard on imported records.

Yet from the start, Brit-Funk records also displayed influences that were more homegrown in nature and reflective of contemporaneous musical activity in post-industrial British towns and cities. There was a refreshing rawness and do-it-yourself sensibility inspired by punk, but more significantly the softly spun, wide-eyed soul of lovers rock and a loose, rhythmic shuffle inspired by Caribbean musical culture. While a number of bands – and the audiences that bought their records – were multi-racial, Brit-Funk was unarguably an expression of Black British identity, albeit one that largely eschewed political messaging in favour of party-hearty escapism.

As with many British dance music movements since, Brit-Funk has been framed as being London-centric in nature. The sound certainly first took root there and in the wider South East region, with key local DJs and pirate radio stations championing important tunes and soul-focused record stores becoming go-to spots to pick up now sought-after white label releases (two of which by Freeez, ‘Keep In Touch’ and ‘Stay’, are soon to be reissued).

Yet there were also exponents of the style scattered around the country and the records found favour in both the nation-wide soul all-dayer scene and the underground, inner city clubs that provided a weekly stomping ground for its most dedicated and expressive dancers.

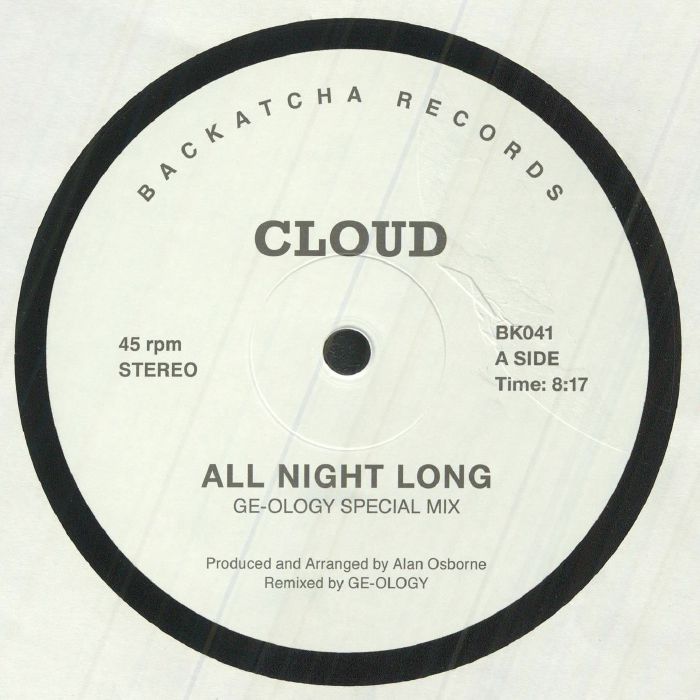

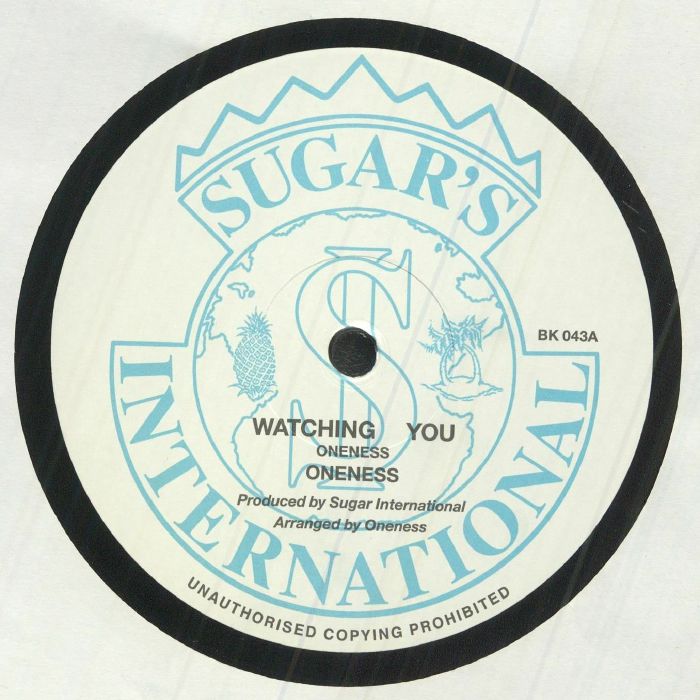

The results of this nation-wide spread, albeit sometimes on a niche level (only a handful of records, such as Freeez’s ‘Southern Freeez’, ever made the higher echelons of the pop charts) can be heard in some recent reissues from the admirable Backatcha label. Of these, Cloud’s ‘All Night Long’ was one of the first records to emerge from the West Country’s overlooked jazz-funk scene., while another, Oneness’s ‘Watching You’ has an even more intriguing back story.

It was the sole single from a roots reggae band from Leicester who had been persuaded to try their hand at “crossing over with a more mainstream sound”, according to producer Dennis ‘Sugar’ Christopher. Their reticence can possibly be partially explained by the animosity that sometimes existed between members of the soul and reggae scenes at the time.

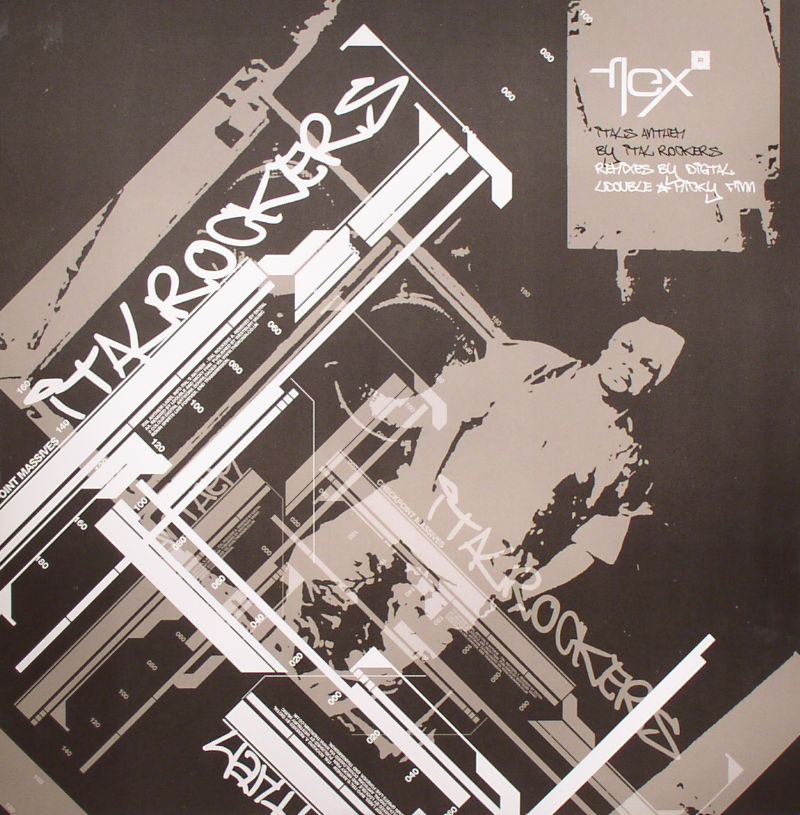

In fact, many of the young Black Britons who travelled around the country to dance at all-dayers grew up surrounded by soundsystem culture and loved it too; years later, one of these dancers, David Duncan, would go on to make one of the most significant early bleep techno anthems of all, Ability II’s insanely bass-heavy ‘Pressure Dub’, with help from another soul boy turned sub-powered techno futurist, LFO founder member Martin Williams AKA DJ Martin. UK dub stalwart Mark Iration, founder of the Iration Steppas soundsystem, is another great example; while he was always a reggae DJ and producer at heart, his first soundsystem, Ital Rockers, initially caused consternation in the blues clubs of Chapeltown, Leeds, by playing electro, hip-hop, soul and house alongside dub, roots, steppers and lovers rock.

By the time Ital Rockers was making a name for itself in the late 1980s, the winds of musical change were turning into a gale. Brit Funk had been surpassed in popularity by electro and acid house, styles which were first embraced in the UK by black DJs and dancers – or those white DJs whose weekly club crowds were dominated by jazz dancers and footworkers. Both styles were particularly strong in the North and Midlands but were also championed by former ‘soul sounds’ in London and many DJs and producers who would later go on to make or popularise early UK techno and hardcore records (A Guy Called Gerald, Fabio & Grooverider, 4 Hero and the more hip-hop influenced Shut Up & Dance in particular).

It was not an instant shift, of course, with rare groove – itself a style rooted in classic funk and soul – coming in between. This scene was undoubtedly important, not least because it was initially championed by former jazz-funk and Brit-funk enthusiasts (Gilles Peterson and Norman Jay amongst them) and led to some of the first unlicensed warehouse parties in the UK – a trend that of course grew quickly once acid house and Ecstasy began to become popular from 1987 onwards.

Brit-funk was where it all began though. Whether or not it should be considered Britain’s first genuinely revolutionary dance music movement is a contentious subject; Northern Soul, which introduced DJ culture to the UK, preceded it, and subsequent UK-pioneered styles of dance music were certainly far more sonically revolutionary and culturally significant. Either way, it’s about time the sound and the role it played in the evolution of British dance music culture is more widely recognised.

Matt Anniss