“Difficult to live with but impossible not to love” – full Richard H Kirk obituary by Matt Anniss

Sheffield scene expert Matt Anniss on his meetings with the reclusive Richard H Kirk

In the hours and days following a death of a musical icon, it can be hard to make sense of their career and the impact of their work. Assessing the legacy of an artist is hard enough in the best of times but is rendered near impossible when your brain is scrambled by the news of their passing.

In these circumstances, it’s usual to coldly state the facts, reeling off a list of career milestones and sonic touchstones. Yet when it comes to Richard H Kirk, this seems like a futile and hollow gesture; after all, he amassed a ludicrously deep and varied discography during a recording career that lasted the best part of five decades, was renowned as both a collaborator/group member and a solo artist, and his overall contribution to the development of electronic music may only be fully understood in the years and decades ahead.

Since news of his death was announced, I have been looking back over transcriptions of old interviews I did with him and some of his many collaborators from the Sheffield scene. My mind has also drifted back to our first ‘in person’ encounter at the Forum in Sheffield, nigh on 20 years ago. I was back in my home city to try and chronicle the Steel City’s then contemporary music scene for a magazine article, and the meeting with Kirk had been set up so he could provide some historical context.

I arrived at the venue early, picked a table and waited. 15 minutes later, Kirk ambled in, looking all the world like a militant, punk-era socialist activist who had let himself go. Decked out in East German army surplus clothing with a mess of faded magenta hair, he cut a striking if unusual figure. In typical Sheffield fashion, he was dour and down-to-earth, prone to grumbling – in the Steel City, moaning has been turned into an artform – and undeniably self-deprecating when discussing his work.

At the time, Kirk had just received copies of a suitably challenging 12” he’d made for German label Die Stadt, Aural Illusions, under the one-off Digital Terrestrial alias. As the interview ended, he handed me a copy and said: “You probably won’t like it. Most people don’t get to the end.”

For the record, I did get to the end, and that record still sits in a forgotten corner of my collection. It’s not one of my favourite Kirk productions – even by his standards, it was abstract, difficult and challenging – but in a weird way it only emphasized the opinion I had of him at the time, namely that he was a genuine musical one-off who did whatever he liked creatively, with scant regard for whether it would find an audience or sell in significant quantities.

In terms of his Sheffield contemporaries – those who emerged during the punk era – Kirk was unique. While it’s important to recognise the role played by his original bandmates Chris Watson and Stephen Mallinder in the development of the Cabaret Voltaire sound – they too were committed experimentalists with similarly militant political views and a desire to upend the existing cultural and political consensus – there’s no doubt that Kirk was the brooding, intense and at times confrontational heartbeat of the band.

“I interviewed Cabaret Voltaire several times and Richard could be hard work,” former I-D journalist Vaughan Allen told me during the research for my book Join The Future: Bleep Techno and the Birth of British Bass Music. “He spent most of the interviews talking about pornography. He was a very different character from Mal, who was lovely. I can forgive Richard though, because it was partly that aspect of his character that made him one of the true geniuses of pop music.”

As he grew older, Kirk became increasingly protective of his work and legacy, complaining privately – and on occasions, in interviews – about the way in which some of Cabaret Voltaire’s music had been framed and analysed by certain media outlets. It particularly irritated him that some critics only saw worth in the band’s mind-altering and dystopian early works, where jagged guitars, mind-melting electronics, music concrete style sound collage and droning vocals leapt to the fore.

“A lot of people say, ‘Cabaret Voltaire weren’t any good after Chris Watson left’,” Kirk complained in an interview we did for Juno Daily’s forerunner, Juno Plus, in 2013. “There was a recent article in a magazine that more or less rubbished everything I’d done, and Mal and I had done, after that. They said everything after 1981 was crap. That hurt. There seems to be this idea that we moved to Virgin Records for money and spent all this cash on clothes and eyeliner. That’s absolute rubbish!”

Kirk was rightly frustrated (in my opinion at least) that Cabaret Voltaire’s musical evolution in the 1980s, and specifically their contribution to dance music culture, was looked down on by electronic music snobs. Yet this aspect of Kirk’s career, which continued well into the nineties and beyond, is arguably even more important than his contributions to experimental and industrial music. There’s no doubt that Kirk “got” dance music, with his solo and collaborative productions helping to shape and define UK techno (and its more horizontal downtempo offshoots) during the second and third decades of his career.

The Cabs had always looked to black music culture for inspiration, particularly funk, soul, dub and reggae, but by the time they released The Crackdown in 1983 it was the electro sound of New York that was influencing them most. They developed a distinctive brand of industrial funk that sounded like it had been forged from Sheffield steel, with the band’s experimental sampling techniques and use of muddy tape loops being incorporated into a sound capable of rocking dancefloors.

This continued throughout the 1980s, with Kirk and Mallinder’s interest in dancefloor dynamics only intensified via frequent trips to local clubs, most notably the Jive Turkey party helmed by DJs Parrot and Winston Hazel (a pair who in 1986 became the Cabs’ tour DJs). During the same period, they also opened their notorious Western Works studio – a former cutlery workshop turned Sheffield Socialist Workers Party HQ – to aspiring local bands and DJs, in turn inspiring one of those bands, Chakk, to follow in their footsteps with their own FON studio.

“We told our label MCA that we would only sign on if we could use the entire recording budget for the album to build a studio,” Chakk’s Mark Brydon told me in 2018. “That’s the way the Cabs had done it with Western Works. We wanted to have the means of production.”

When CHakk’s career stalled and their deal with MCA ended messily, they were left with a state-of-the-art studio and lots of free time. To try and make use of their asset, Brydon and FON’s in-house engineer, Rob Gordon, invited local bands and DJs into the studio. With their assistance, a number of these made records that became surprise hits, most notably Krush (with early UK house cut ‘House Arrest’) and Funky Worm (the disco-sampling, rare groove-goes-pop-house fun of ‘The Funky Worm’).

During the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, Kirk’s impact on underground dance music culture was immense. He was inspired by the rapidly evolving Yorkshire club sound epitomised by Unique 3’s ‘The Theme’, Nightmares on Wax’s ‘Dextrous’ and Forgemasters’ ‘Track With No Name’, the latter co-produced by Rob Gordon, Winston Hazel and Sean Maher. “Everything made here sounds hard,” he explained to I-D Magazine’s Simon Dudfield for a 1990 feature on the rapidly emerging bleep techno sound. “Perhaps it does have something to do with the [industrial] heritage.”

Bleep & Bass was right up Kirk’s alley, combining as it did metallic industrial sounds, unholy dub bass-weight and unearthly, sci-fi melodies; it was the sound of Sheffield, Leeds and Bradford producers hammering Motor City techno into brutalist new shapes. It now seems fitting that the Cabs made some killer bleep tunes of their own – most notably 1990’s ‘Easy Life’, but also much of 1991’s Body & Soul album – but more significant were Kirk’s contemporaneous production partnerships with DJ Parrot (real name Richard Barratt) as Sweet Exorcist, and Rob Gordon as Xon.

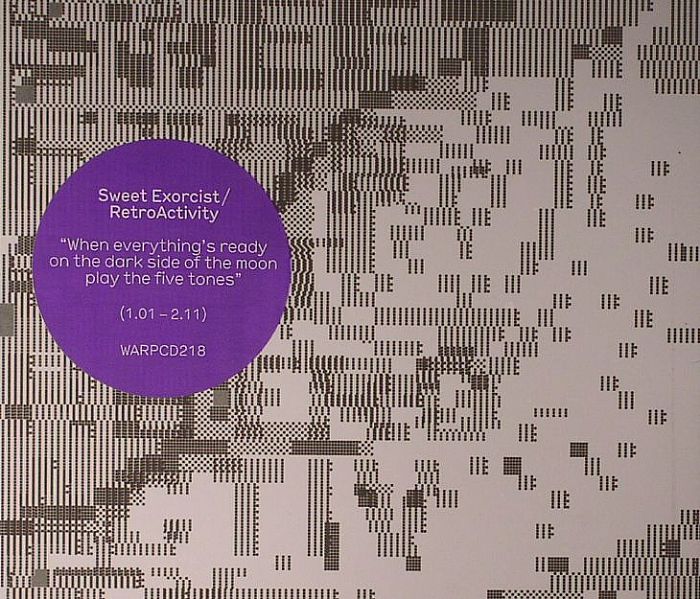

While the latter project sadly only resulted in a sole release, a three-track EP of ghostly, uneasy and inspired UK techno entitled The Mood Set, the impact of Sweet Exorcist’s techno explorations was immense. The pair’s debut single, ‘Testone’, is an early bleep techno touchstone that inspired countless pale imitations. Their follow-up EPs, marketed as “clonk” rather than “bleep”, were clanking, sub-heavy masterpieces marked out by nods to the polyrhythms of Africa (something Kirk later explored further in his solo work as Sandoz) and a keen desire to avoid the formulaic constraints of a musical sub-genre they’d helped to develop.

Sweet Exorcist’s music was largely released by Warp, a label whose early dalliances with industrial-strength techno and futurist IDM were intrinsically linked to the electronic sound of Sheffield that Kirk had played such a significant role in developing. As his relationship with Mallinder soured and the Cabs stumbled towards a lengthy hiatus (Kirk eventually brought Cabaret Voltaire back as a solo project in 2019, 25 years after 1994 swansong The Conversation), his productivity increased, with new projects for Warp and other labels that fully displayed the breadth of his electronic vision.

This period, which extended well into the early 2000s, included some of Kirk’s most significant solo works. 1993’s Virtual State on Warp, an evocative and heady voyage through chill-out room-era ambient, IDM and ambient techno, remains a standout, as do his two albums on Beyond as Electronic Eye. The latter are hard to pigeonhole but draw far more deeply on the influence of dub than any of his other projects bar Sandoz. Kirk’s albums and EPs under that alias, fired by the twin obsessions of dub and Afro-futurism, are uniformly timeless and a natural evolution from his bleep-era work.

The pull of experimentalism was always strong though – as was his increasing desire to properly catalogue and document a lifetime’s work – and during the latter stages of his life Kirk once more returned to the cutting-edge, abstract and militant electronic sounds that had been his calling card since the 1970s. Releases packed with archive experiments, most of which had sat on tapes in his attic for decades, frequently appeared, alongside new albums inspired by his long-held paranoia at the extent of Britain’s surveillance infrastructure. In hindsight it is fitting that his final releases were as Cabaret Voltaire, variously exploring drone, ambient, industrial and bleak, dystopian techno.

Kirk’s obsessive archiving mean that we likely haven’t heard the last of him. He amassed a vast vault of recordings over the years, only a fraction of which have ever been released. In the years ahead, I’d expect a number of posthumous releases, each of which will provide a further glimpse into the mind of this most unique and forthright of musical visionaries.

Finding words to accurately describe Kirk’s career, character and contribution to music will remain difficult for some time, though these words from Stephen Mallinder, tweeted shortly after his former bandmate’s death was announced, sum up how many of us are feeling: “Difficult to live with but impossible not to love. Stubborn, no sufferer of fools, but insightful, spontaneous, and with vision… and underneath the spiky shell a warm heart. I’m truly devastated. RIP Kirky.”