Vincent Floyd: Get Closer

Richard Brophy tracks down Vincent Floyd to discuss the Chicago artist’s emergence during the birth of house music and his renewed passion for production.

Some day, someone with enough time and resources will write the definitive story of Chicago house and all of its protagonists. When that happens, Vincent Floyd is sure to feature. The author of a small but distinguished catalogue, Floyd was there at the start, released on a number of the city’s key labels, and then like so many of his peers, seemingly disappeared off the radar into obscurity. One of the more positive aspects of reissue culture is its potential to shine a light on key artists who are no longer in the spotlight.

In Floyd’s case, this happened courtesy of Rush Hour boss and crate digger par excellence Antal Heitlager, who contacted the Chicago artist to put out some of his early records. Before we get to that part of the story, however, we go back in time.

Floyd is a proud native of the city he still resides and affirms that he was “conceived, born and raised in Chicago”. From an early age, he was involved with music and was also close with Armando Gallop, the producer of landmark acid records like Land of Confusion and House Music All Night Long, who died of leukemia in 1996 aged just 26.

“I’ve always been a huge music fan in general. I started playing guitar when I was around 11 years old – my uncles were musicians and they inspired me a great deal, along with Armando’s brother, Pedro, who played the trumpet,” Vincent explains.

“I played rock, blues and R&B on guitar first,” he says. “Armando was certainly the person who geared me towards making house music. He was one of the first people in the area with a Technics set up and he had a Roland 707,” he says. “I thought the Roland 707 was the coolest thing on the planet at the time,” he adds. “That’s when I first became fascinated with electronic instruments.”

When Floyd and Armando were still in their early teens, the first wave of house music started to sweep through Chicago’s clubs and being under age couldn’t keep them away from it.

“Somehow Armando and I got into clubs,” Floyd starts. “In retrospect, it was kind of crazy because we were around 13 or 14 years old,” he says. “I can’t remember how we got in, but we were always hanging out.” However, it wasn’t just in clubs where people were picking up on house music, and I put it to Floyd that the period between the middle to the end of the ‘80s must have been a crazy time generally in Chicago.

“Yeah, house as a culture started getting big when I was in high school. It wasn’t just the music; there was a look, style and attitude that went along with it,” Floyd says. “There used to be radio stations that played it and I went to a high school that had house music parties every Friday that were very popular,”.

Just being part of the party crowd wasn’t enough for Floyd and by the end of the ‘80s he and Armando were directing and running parties in the city. This is the “day job” Floyd was referring to in a recent, brief interview with Heitlager on the Rush Hour website.

“When we started, the parties were geared towards high school students and they were mostly held at a club called The Humming Bird,” Floyd begins. “We worked for ourselves so it wasn’t like a day job, it was more like an all day and night job,” he remembers.

“Back then we ordered hundreds of posters and put them on street poles in the middle of the night. We passed out flyers at the schools in the morning and afternoon, we really could have used Facebook back then,” Floyd adds. “We did this for a number of years and then later promoted 21 and over parties at various venues.”

Floyd followed Armando’s lead and also started producing. Given his musical background, it’s no surprise Floyd’s records are musical, almost virtuoso-like in places. 1990 saw the release of his debut record, Cruising, an expansive, 12-minute cosmic serving of proto-deep house. On the flip side, Floyd maintains this introspective sound with the warm, psychedelic keys of “Isolation” and the disco-fuelled “Silent Noise”.

Does he agree that his early productions were closer to the sound of Larry Heard than Phuture or Armando? Floyd answers indirectly: “When I was younger, I always asked for records as Christmas gifts from my parents. The first records that they purchased was Prince, who is all about going in different directions, and that is really the philosophy I follow and strive for.”

Does he agree that his early productions were closer to the sound of Larry Heard than Phuture or Armando? Floyd answers indirectly: “When I was younger, I always asked for records as Christmas gifts from my parents. The first records that they purchased was Prince, who is all about going in different directions, and that is really the philosophy I follow and strive for.”

Jamie Principle’s “Waiting on My Angel” and Larry Heard’s “Can You Feel It” were the first Chicago house songs Floyd fell in love with and inspired his sound. “As far as I am concerned I really don’t have a particular sound. It’s my desire that people see me as who I am musically, and that’s a musician with diverse styles of expression,” Floyd says.

Despite this assertion, Floyd’s next record, Your Eyes, which features another childhood friend, Dwayne ‘Chan’ Chandler,on vocals, saw him push further into what’s described as a spiritual direction. Waves crash in, a Spanish guitar lilts gently in the background and Chandler’s wonderfully warm vocal about absolute, unequivocal love unfolds over bongo drums. Originally released on Dance Mania, Floyd recalls how the record came about.

“I knew Ray Barney at Dance Mania from going to his record store and he released records for a lot of people that I knew. I let him hear some of my music and it was a go,” Floyd says. “It was the same thing with Cajmere; I knew him and just let him check out my music.”

Floyd’s proximity to his peers also saw him tour the US and Asia with Larry Heard in the ‘90s – Google images searches return blurry shots of them together on stage or dressed in the same outfits backstage. Despite being based in Chicago, was Floyd aware of the major impact that house music was having in clubs and society generally in Europe?

“I knew about what was going on in Europe from being in a circle of people who produced and DJed house music,” he says, but adds with a tinge of regret that his chosen form did not get as big as it should have first time around.

Like Detroit techno’s inability to break into the mainstream – with the exception of Kevin Saunderson’s Inner City project – Floyd feels mass media simply didn’t want to get behind house music.

“I am certain that more radio play would have made it more popular,” Floyd says. “To me, house music is popular because that’s what I am into, but of course I don’t see any of the house music artists that I love on TV in the same way that I see mainstream artists,” he says. “As far as I am concerned Larry Heard should have 10 Grammys, but the system isn’t set up that way,” Floyd believes. “Promoting sexiness, throwing money in the air and creating shock value is what the pop industry likes to market the most.”

After a few more releases in the ‘90s Floyd seemingly faded into obscurity. The reality is that as a single parent he had to support his family with a day job, but he never ceased his involvement in music and apart from continuing to produce, he also taught it.

After a few more releases in the ‘90s Floyd seemingly faded into obscurity. The reality is that as a single parent he had to support his family with a day job, but he never ceased his involvement in music and apart from continuing to produce, he also taught it.

“There wasn’t a conscious decision to not release anything. I am a musician and have always been involved in music. It could be playing guitar, teaching, engineering, writing, or producing,” he explains, adding: “Of course I take breaks to experience life and be inspired, but I am a musician and studio junkie. I love playing and working with music equipment.” Floyd is also quick to dispel the myth of a Chicago producer from back in the day being plucked from obscurity, “I have always been making music,” he says, cryptically, adding, “some nice tracks that were released under various pseudonyms”, while his track “Images of Spring” featured on a 2002 compilation called This Is House Music alongside producers like Boo Williams, Ron Trent, Glenn Underground and Roy Davis Jr.

It was the early ’90s track “Your Love”, however, that reintroduced Floyd’s records to a new generation via a rerelease last year on Rush Hour. I asked if Floyd was surprised that there was still interest in his music?

“Yes, I was pleasantly surprised – it’s good to know that my mom, granny and daughters aren’t my only fans,” he says.

Despite being shunned by mainstream radio and TV in the US first time around, electronic dance music has mushroomed in popularity over the past few years. An unintended consequence of EDM becoming the dominant form of popular music is, laughably enough, a voracious appetite to achieve house music’s authenticity, a trend that includes the cookie-cutter big room sound to the underground’s hunger for Dance Mania or Soichi Terada reissues.

There is no doubt Rush Hour’s approach to Floyd was timely, but what does an artist like Floyd, who was there from the start, make of this renewed interest in house music?

“If they are doing it because they actually love the music that’s cool; but if they are doing it because they want to be trendy, people will know and act accordingly,” Floyd believes

Unfortunately, Floyd, like so many Chicago producers, has suffered at the hands of unscrupulous forces; Cruising was bootlegged in 2011 and the following year I Dream You was subjected to the same treatment. In particular, the unofficial version of I Dream You continues the regrettable practice of bootleggers not even pretending to care about the sound quality – it was not remastered and has background noise throughout.

“I look at it two ways,” Floyd says. “First, I have always had the money to re-release the records. I should have been more involved and not have given the bootleggers a chance to press my material. Second, I see bootlegging as the worst kind of violation; I compare it to kicking down my front door and stealing my children.”

Bootlegging is nothing new, unfortunately, and it seems to have been especially prevalent in Chicago right from the start of house music.

“I suppose that the bootleggers feel that they can steal from Chicago artists because they don’t think that we will find out who they are, but I have already been given a lot of information on who these people are and it will be handled in due time,” Vincent adds.

Thankfully shady behaviour hasn’t hampered Floyd’s re-emergence. The first reissue on Rush Hour was followed by an EP of unreleased, deeper house tracks, Moonlight Fantasy, at the tail-end of 2014 and then a CD version which featured additional, unavailable material at the start of this year.

“These tracks were recorded at various times in the ‘90s. It is my desire to continue to put out more of my unreleased music as well as new material with Rush Hour. I would also like to work with other artists from around the globe,” he says.

Floyd, who claims to have a huge bank of unreleased material in his studio, appeared to have been energised by the hook-up with Rush Hour, and, he says, “I am working on re-launching my record label, I have a new Chan record that I am working on and some remixes – my heaven is a studio with a comfortable chair.”

Interview by Richard Brophy

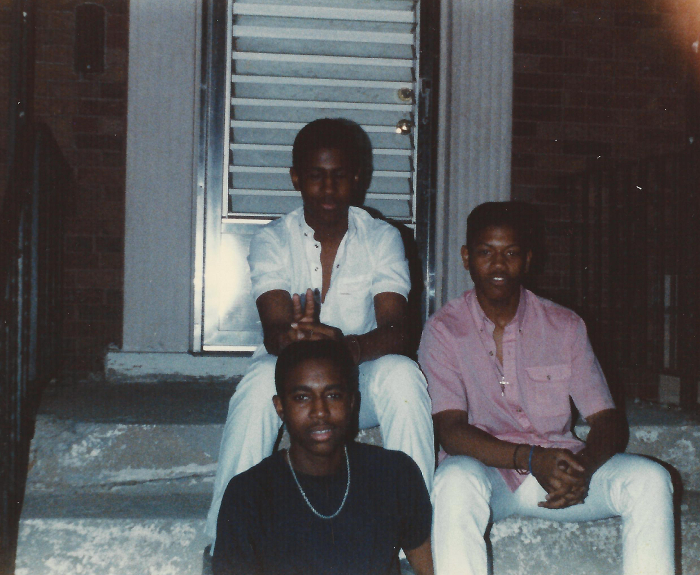

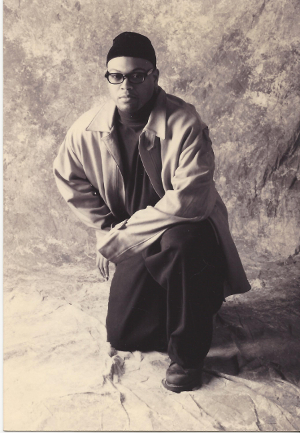

All images provided courtesy of Vincent Floyd

Moonlight Fantasy by Vincent Floyd is out now on Rush Hour Music