Diagonal: Funny Lines and Dangerous Angles

The Diagonal label has been injecting some humour into the typically serious world of techno and industrial electronics. Scott Wilson sits down with the minds behind it to talk about the club, sleeve design and glowsticks.

“I used to be really into drawing, into shapes, and I’ve always been really drawn to sharp lines, hard edges, squares,” Oscar Powell tells me when I ask what inspired the name of the Diagonal imprint he runs with close friend Jaime Williams, who I’m sitting with in a Soho pub with, alongside the label’s sleeve designer Guy Featherstone (all pictured above, left to right). “I love lines, sharp things. There’s something quite dangerous about angles y’know, you see an angle cutting through a picture like a diagonal – even going back to the Renaissance artists who used to put a diagonal right through the middle of their painting to add danger or energy.”

The idea of danger and perspective is something that seems to run through not just Powell’s music, whose frazzled post-punk informed techno bounces like a wayward ball of rubber and fleshy pulp, but also his DJ sets, which mix jungle, post-punk, techno and EBM together in a manner he describes to me as “collage”. This isn’t pleasant collage, but jarring, breakneck and unpredictable stuff. “Things fly out, anything can happen at any moment, I get off on that,” he explains with a slightly manic glint in his eye. “I grew up listening to D&B, and someone like Andy C – when we were 16 years old he was like a God to us – just did the most intense, rapid, fast mixing and bringing stuff in. After about eight bars he already had something else in the mix.”

The artists picked for release on Diagonal are just as varied as Powell’s sets. There are few labels currently operating who would have the guts to release the alternative hip hop of Stuart Argabright’s Death Comet Crew, an album of skewed club music from noise veteran Russell Haswell and the scorched industrial of Blood Music. It’s not just this eclecticism that characterises Diagonal, but a healthy dose of humour as well. Powell’s Melon Magic show on NTS embraces its Friday timeslot of 11pm – 1am, bringing the chaotic atmosphere of a late night weekend TV show from the ‘90s to internet radio, where technicals are part of the charm and the studio onlookers are as much a part of the action as the music. Its name is a pun on Magic FM’s Mellow Magic, well aware of the irony that their music is often confrontational.

Their infrequent parties are just as anarchic. A few months ago Diagonal took over room two of Corsica Studios for one of their biggest events to date as part of BleeD’s second Leitmotif night. Despite Powell, Haswell, Vereker and Evol all playing the kind of techno sets that pushed the boundaries of the term “banging”, it was the attention to detail that made the event unique, with those arriving early handed a bespoke Diagonal branded glowstick with the slogan “Club Shit Innit” emblazoned across it. It was a humorous gesture which felt quite at odds with the comparatively more serious activities of Hospital Productions in room one, where there was a moody live A/V set from Silent Servant, a bracing performance from Vatican Shadow and a heads-down techno set from L.I.E.S. boss Ron Morelli. Powell asks me whether I liked the glowsticks, and I tell him that I did.

“Some miserable fuckers hated them,” he says proudly, and the table erupts into laughter.

“We want that sense of humour to be at the centre of everything we do,” Williams explains, “so we think of things like the glowsticks as being a good way of communicating some of that. It might fall on deaf ears occasionally, but I think our sort of people get it. Eventually every party fades into the last one, but we like to think the people who came to the last one we did may have picked up a glowstick, and whether they put it down the toilet or whether they put it on their mantlepiece, they’ll still remember that they got it at our party.”

“I hope that people got back after that night and thought ‘those fucking glowsticks eh?’” Powell says with a laugh. “Even if you didn’t like them, people will remember that shit.”

The people behind Diagonal are remarkably self-assured in what they do considering the label is only 11 releases old, and was originally started as a means for Powell to release his own material. Following two critically acclaimed EPs, he enlisted the help of Williams to run and develop the label, and last year Diagonal released its first record from an outside artist in the form of Blood Music’s self-titled EP of live post-punk and industrial sounds. Since then a number or underground and high profile figures have gravitated towards the label, including respected noise veteran Russell Haswell, cult artist Shit & Shine, the prolific noise-techno producer Prostitutes and Bronze Teeth, the new project of Factory Floor’s Dominic Butler and Richard Smith, who recently released as L/F/D/M on Optimo Music. A few years ago it wouldn’t have seemed possible to find one artist that reflects Powell’s anarchic style, but somehow the label has managed to assemble an entire team of delinquent producers who fit logically under the Diagonal banner.

Though parallels can be drawn between the music released by Diagonal and that of labels like Blackest Ever Black, Downwards and Berceuse Heroique the same can’t be said of the label’s striking sleeve design, which cuts a colourful swathe through what can sometimes be a clichéd and monochromatic world. The original Diagonal logo was designed by Powell and his friend Andy Cooke, and the first few sleeves were designed by Powell himself, who had a very “specific vision” of what he wanted the label’s visual aesthetic to be.

Though parallels can be drawn between the music released by Diagonal and that of labels like Blackest Ever Black, Downwards and Berceuse Heroique the same can’t be said of the label’s striking sleeve design, which cuts a colourful swathe through what can sometimes be a clichéd and monochromatic world. The original Diagonal logo was designed by Powell and his friend Andy Cooke, and the first few sleeves were designed by Powell himself, who had a very “specific vision” of what he wanted the label’s visual aesthetic to be.

“In my head I wanted it to be fun, taking the piss a little bit but also hyper-modern, because I personally felt that everything at the time was so retro,” Powell explains. “There’s this whole retro thing about music – everything’s rooted in something that could have happened in the ’80s, but I thought ‘fuck that, we’re gonna try and brighten things up and do something which is of the moment.”

It wasn’t until he got veteran designer Guy Featherstone on board that the label design really took shape, finding in Featherstone a like-minded person with an enthusiasm for using the vinyl format as a canvas who was able to interpret Powell’s ideas visually “a thousand times” better than he could. Although Featherstone now works as a design director at Wieden & Kennedy, the same advertising agency Powell worked at until recently, in the ‘90s he designed sleeves for both subsidiaries of major labels, and independents like hip hop label Low Life. When music started to move away from the vinyl format, Featherstone’s interest in sleeve design waned.

It wasn’t until he got veteran designer Guy Featherstone on board that the label design really took shape, finding in Featherstone a like-minded person with an enthusiasm for using the vinyl format as a canvas who was able to interpret Powell’s ideas visually “a thousand times” better than he could. Although Featherstone now works as a design director at Wieden & Kennedy, the same advertising agency Powell worked at until recently, in the ‘90s he designed sleeves for both subsidiaries of major labels, and independents like hip hop label Low Life. When music started to move away from the vinyl format, Featherstone’s interest in sleeve design waned.

“I got out of it when CDs came on the scene in a bigger way, and every job I was getting was going to CD but not pressing on vinyl,” he explains. “I wasn’t interested in that, because the art dies as soon as it goes behind a jewel case or goes into a digipak. Liner notes in PDF? No thank you. So my motivation for doing stuff for these guys was when they told me they were doing vinyl.”

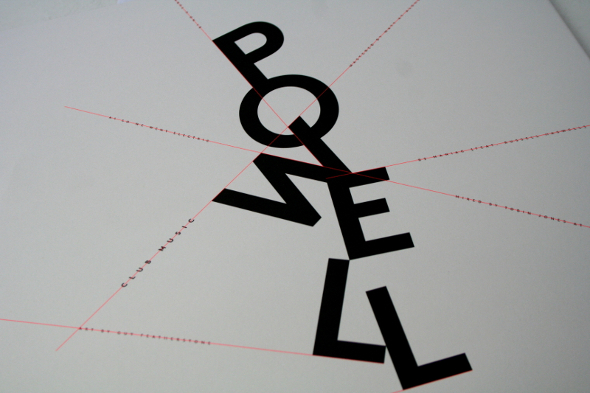

Featherstone’s work to date has reflected this perfectly, most notably the sleeve for Powell’s recent Club Music EP, where Powell’s name is assembled in letters to look like an animated likeness of imposing frame. It’s perhaps the best example of Featherstone’s design values for the label, which he describes as “oozing modernity and simplicity, celebrating space and cleanliness.”

“The brief on Club Music was to try and portray a bit of that levity,” Featherstone explains, “a bit of that ‘let’s not be all up tight and looking inward and at ourselves too seriously’. Let’s play with it a little bit. I think when you look around, the world is pretty dark, and where it’s very geometric, or so razor-sharp that you can cut yourself, it’s all a bit pre-subscribed. There’s no real personality there, no joy to it, so the brief from these guys on that particular Powell sleeve was to see how we can have a bit of fun with trying to portray trance, dance, club music, techno. If you boil all of those sounds together, how can we do it in a fun, playful way? It was about getting away from big expanses of lucid colour, and just being playful with typography.”

Featherstone’s unique perspective might be partly to do with the fact he has some distance from the music itself, which he admits to not having much affinity with. Rather, it’s the values of the label Featherstone recognises, which he sees as having some of the spirit of his chosen genres of jazz, funk and punk. “I like music that sort of rubs up against society, that has a point of view, that’s got a form of expression and that’s slightly anarchic,” he explains. “That’s where I’ve got an affinity to Diagonal: I feel there’s a sort of tension that’s almost kind of like a petulant teenager in the sound.”

Featherstone’s unique perspective might be partly to do with the fact he has some distance from the music itself, which he admits to not having much affinity with. Rather, it’s the values of the label Featherstone recognises, which he sees as having some of the spirit of his chosen genres of jazz, funk and punk. “I like music that sort of rubs up against society, that has a point of view, that’s got a form of expression and that’s slightly anarchic,” he explains. “That’s where I’ve got an affinity to Diagonal: I feel there’s a sort of tension that’s almost kind of like a petulant teenager in the sound.”

His sleeve for the recent Bronze Teeth record is a case in point. The record’s title, O Unilateralis, is spelled out in shocking pink and orange letters, fractured and overlaid in a manner that suggests they refuse to sit still on the page, much like the jittery, ADHD quality of the music itself. While early sleeves for Shit & Shine, Death Comet Crew and Russell Haswell’s records all reflected the music with synaesthesic colour and lucid shapes in an abstract sense, it’s this recent play with words and type that have put Diagonal’s sleeve design ahead of the pack.

While some of his earlier designs have hidden elements like tracklistings and credits, he’s keen for what he’s doing not to be misinterpreted as him being what he describes as “the cliched sort of obligatory ‘uber-visual designer'”. For Featherstone, the overall mood of the sleeve is the most important thing. “When you’re listening to music, it’s about what you’re feeling and experiencing,” he believes, “it’s not about every individual instrument in the sound.” Conveying this kind of mood through typography is something Featherstone sees as “the blueprint to the label”, a tool with which he can “create a lot of chaos, and evoke a lot of emotion.”

“For me the idea of club music isn’t just the music, it’s everything that comes with it, seeing your mates, hanging out with people you know, people doing similar things to you. That’s the spirit that I think I want the label to represent.”

Featherstone might be the person who brings Diagonal to life visually, but it’s clear that in terms of the music selected for the label it’s an equal split between Powell and Williams, who first met when they were 13. Though Williams admits to the two knowing each other so well that quotes from The Office find their way into their meeting agendas, it’s Williams that feels like the one keeping the whole operation on the straight and narrow, especially now that Powell has quit his job to pursue his music career full-time. If Powell is the lanky devil on Diagonal’s shoulder, then Williams is the angel, albeit the practical one who’s also an accomplished house and techno DJ in his own right, regularly posting mixes on SoundCloud.

“I’ll tell you what an average day looks like,” Powell tells me, “I’ll wake up, send a few emails back and forth with Jaime, he’ll resign, I’ll persuade him not to resign, we’ll have a massive fucking barney and then we’ll get back together in the evening to get together to have a few pints to talk about what we’re gonna do next,” Powell says with a laugh.

“It doesn’t sound productive, but it is,” says Williams.

Whether the pair really do argue as much as Powell makes out, and whether they have come to “fisticuffs” as he suggests is unclear, but when they do talk, an almost telepathic link can be detected. “When it comes to working out what the music should be, what our next release schedule looks like, it’s all very collaborative,” Williams explains. “What it all comes down to in terms of what music we sign is ultimately about two people who have known each other since they were tiny, and who have a shared idea of what makes really great music. The first thing we think when we listen to demos is whether we really fucking like them or not. I don’t think there’s a theory behind it – but we kind of have an unspoken way of working out whether it fits within who we are.”

While the label is arguably more fully formed than most, what exactly constitutes Diagonal as a whole and how it operates is something that the three are still working out. Williams admits to having “failed” with the accounts, drafting their friend Jez Johnson to manage their books, while also talking in glowing terms of everything the label’s new distributors Boomkat have done to assist them. Featherstone admits that he’d like to create a set of parameters and values by which Diagonal’s artwork can abide by, with the intention of allowing other designers the opportunity to see how far they can stretch the concept, with the option of taking the visual identity off the sleeve and into the club. Powell meanwhile was recently commissioned to do a remix for Nicolas Jaar’s Other People label, which uses a subscription model to deliver music to its fans every week, something he sees a particularly intriguing model.

While the label is arguably more fully formed than most, what exactly constitutes Diagonal as a whole and how it operates is something that the three are still working out. Williams admits to having “failed” with the accounts, drafting their friend Jez Johnson to manage their books, while also talking in glowing terms of everything the label’s new distributors Boomkat have done to assist them. Featherstone admits that he’d like to create a set of parameters and values by which Diagonal’s artwork can abide by, with the intention of allowing other designers the opportunity to see how far they can stretch the concept, with the option of taking the visual identity off the sleeve and into the club. Powell meanwhile was recently commissioned to do a remix for Nicolas Jaar’s Other People label, which uses a subscription model to deliver music to its fans every week, something he sees a particularly intriguing model.

“He’s pushing the boundaries of what music can be in this age, and not many people have got the balls to do that,” Powell believes. “We’re stuck in the mindset that we have to be authentic and authentic is vinyl only. There’s a place for that, but similarly the people who started putting out vinyl did so because it was the format of the day. I think we all need to start thinking about how we can use the internet and make it a bit cooler.”

Brushing my joke aside that Diagonal might be heading towards becoming a lifestyle brand, it’s clear that what Diagonal does know is that it wants to shake up the club space to reclaim it from po-faced monotony, and it doesn’t seem coincidental Powell’s last record was called Club Music. “There’s just something a bit fun about the club,” Powell explains. “We like the rough and tumble of it. It’s a place to dance as much as it is a social destination, and for me the idea of club music isn’t just the music, it’s everything that comes with it, seeing your mates, hanging out with people you know, people doing similar things to you. That’s the spirit that I think I want the label to represent.”

But why “Club Music” and not “Dance Music”? What exactly is so appealing about that term? “I think that we’ve put ‘club music’ at the centre of what we’re trying to do not necessarily because we see ‘dance music’ as a dirty expression,” Williams explains, “but because when Oscar and I sit down and talk about music, we think that music meant for dancefloors so far has been interpreted in a way that’s quite cut and dried, far too genre-based. We like the idea of playing all sorts of records in nightclubs, and thinking about all sorts of music – whether it be a really obscure band, or a really obscure noise track that might still work on the floor with just the same power that a traditional techno record might have.”

“I don’t think of it as stuff that you have to have been listening to Front 242 and be a hardcore goth to be into,” Powell explains. “I want my cousin who thinks he’s into techno to be like ‘I’m gonna come to your party and have a good time’, it’s not meant to be exclusive. We want that to be expressed in everything, and have some fun along the way.”

Interview by Scott Wilson

Header image by Ilaria Pace, from a photo by Nico Engelbrecht

Sleeve design by Oscar Powell and Guy Featherstone