So much noise to be heard: Inside the mind of Hieroglyphic Being

It’s a windy London afternoon and Jamal Moss emerges from his hotel on The Strand, introduces himself and emits the kind of bellowing laugh that immediately puts you at ease. I didn’t know what to expect from the Chicago born producer, DJ and label boss best known as Hieroglyphic Being; email correspondence prior to our meeting was brief and to the point, and I half imagined our conversations to be as awkward and confronting as his discography.

It’s a windy London afternoon and Jamal Moss emerges from his hotel on The Strand, introduces himself and emits the kind of bellowing laugh that immediately puts you at ease. I didn’t know what to expect from the Chicago born producer, DJ and label boss best known as Hieroglyphic Being; email correspondence prior to our meeting was brief and to the point, and I half imagined our conversations to be as awkward and confronting as his discography.

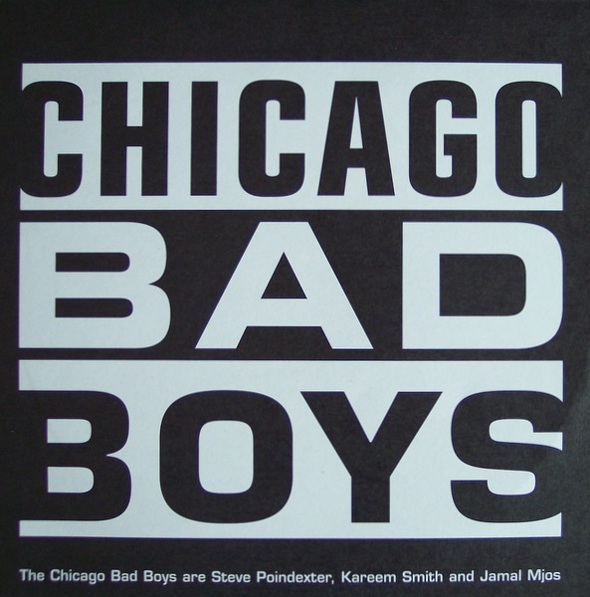

The reality couldn’t be more different: affable and erudite, he cuts an arresting figure, carrying a backpack and wearing a black sleeveless vest showing the arms of a boxer, with dreadlocks hanging down to his waist. To date Moss has more than 50 releases to his name, with material on Jeff Mills’ Axis Recordings offshoot 6277, Djax, Gigolo, Morphine, Spectral Sound and his own Mathematics and +++ imprints. In addition to the Hieroglyphic Being moniker, he works as The Sun God, I.B.M (short for Insane Black Men), and IAMTHATIAM, as well as various, mostly defunct collaborative projects (Africans With Mainframes, Chicago Bad Boys). Equally inspired by the first wave of Chicago house DJs and producers, the avant garde synth-pop of Kate Bush and Laurie Anderson and the cosmic transmissions of Sun Ra and Thelonius Monk, his music is a heady alchemy of grit-encrusted electronic experimentalism and distorted techno laced with acid, jazz, new age and ambient. He calls his style of performance ‘audio texturising’, and often DJs without headphones. “I paint the environment around me with turntables, CDJs or a drum machine,” he explains. “Those are the spectral brushes I use to translate my experiences.”

Moss’s early forays into production came at a time when the precise digital sound of Derrick Carter and Mark Farina ruled the zeitgeist in Chicago, with the somewhat ramshackle DIY aesthetic pioneered by Trax sliding out of fashion. When I last spoke to Moss in 2010 he proudly claimed to be neither “in the now or the know”; two years later his stock has risen considerably – his recent tour of Europe included performances at London’s Royal Albert Hall and Barbican Centre, Poland’s Unsound festival and a slew of intimate club DJ sets. It’s a long way from his complicated upbringing in Chicago’s south side, where he was taken in by his cousins for adoption after his mother left him aged three.

“I was brought up in a very adult environment,” Moss says, and, although he’s reluctant to criticise his adopted guardians (“I had a roof over my head, they kept me fed and kept clothes on my back”), he admits his upbringing lacked the innate caring that comes from natural parents. “I was provided for but I wasn’t nurtured – there’s a big difference,” he says. His adopted father’s existential crisis – he founded his local church before later renouncing religion and then finding God again – taught a young Moss “not to follow, but question, the foundations of society”.

His early musical diet ranged from early bebop to the experimental jazz of Thelonius Munk and Sun Ra. He was given a hand-held radio at age 11 and began tuning in as the sounds of Velvet Underground and DAF coursed through the city’s airwaves. He was encouraged to read widely and the dystopian visions portrayed by of Philip K Dick, Ray Bradbury and Jules Verne provided an escape route from daily life.

His early musical diet ranged from early bebop to the experimental jazz of Thelonius Munk and Sun Ra. He was given a hand-held radio at age 11 and began tuning in as the sounds of Velvet Underground and DAF coursed through the city’s airwaves. He was encouraged to read widely and the dystopian visions portrayed by of Philip K Dick, Ray Bradbury and Jules Verne provided an escape route from daily life.

A teenage Moss started attending parties at the tail end of Chicago’s halcyon era of house music – he never visited the Warehouse and only went to the Muzic Box twice, and on one of those occasions he was rejected for being too young. “For me, the predominant culture growing up was the roller disco scene,” he explains. “The vast majority of parents were super religious and there was a certain time frame you were allowed to be out. Roller derbies were considered Christian, safe and structured.” Nevertheless he says witnessing Hardy in the flesh (he saw him DJ away from the Muzic Box on a number of occasions) was a crucial experience, with Moss watching the legendary DJ – and his crowd – with a hawkish eye. “According to my upbringing, the people at the Muzic Box were heathens who were going to burn in hell – there were gay people, people not from normal society or normal means – but I didn’t see it that way,” he says. “I saw a group of people finding their way to salvation.”

“My creativity saves me from losing my damn mind”

Back at home, his adopted parents stressed the importance of education. “They grew up in an age where they couldn’t sit on the same bus as white people, or be in the same bathroom, and they didn’t have the same access to education. They told me not to take things for granted.” He stuck with school but found growing up on Chicago’s notorious south side a dangerous experience. “Things got tough in my area by the time I was 16,” he recalls. “I’d be walking down the street and there would be a kid who had been at my sleepover birthday party five years before sticking a gun in my side and saying, ‘give me all your money’. I’d go home and tell my family what was going on, but they were in denial. It was kind of like, ‘it’s your problem and you have to deal with it’. I figured, the quicker I got out of school, the quicker I could do what I wanted. So I finished school and that summer I left home with a garbage bag full of clothes.” He spent the next three years as a “nomad”, often sleeping on the street – he once spent a whole summer without a permanent home – and generally survived by staying with friends or sleeping at venues where he helped put on parties.

Although this could easily have led to a life on the nefarious fringes of society, Moss says “I didn’t let the fact I had no means stop me from giving my life meaning.” He adds: “There are resources all around you – that’s one thing I learned from being on the street. If you are on planet earth, there are resources that can keep you going day to day. Other humans are a resource; being kind to other humans is a resource. If you are genuine to them they will help you in the best way they can – with a hot meal perhaps, or with some change.”

His early forays into electronic music production were mixed, and a meeting at Trax Records provides an interesting footnote in his career to date. The label was well established when a young Moss – then still at school – walked in off the street with a friend, tape in hand, and saw an office populated by the likes of Marcus Mixx, Ron Carroll and Steve Poindexter, the latter of whom would go on to become something of a father figure for Moss. “We walked in and Larry (Sherman) kept us waiting for half an hour,” he recalls. “Larry said something like ‘leave the tape with me and me and my people will look over it’. I looked over at someone in the office – I won’t say who it was – and they gave me a look that said, ‘don’t leave the tape with him, whatever you do’. So I took the tape back and walked out.” When I ask him if he looks back on this as a missed opportunity, his response is pragmatic: “I’m not saying I could have been part of history. I could have been there, but now I’m here. I found my way back.”

His early forays into electronic music production were mixed, and a meeting at Trax Records provides an interesting footnote in his career to date. The label was well established when a young Moss – then still at school – walked in off the street with a friend, tape in hand, and saw an office populated by the likes of Marcus Mixx, Ron Carroll and Steve Poindexter, the latter of whom would go on to become something of a father figure for Moss. “We walked in and Larry (Sherman) kept us waiting for half an hour,” he recalls. “Larry said something like ‘leave the tape with me and me and my people will look over it’. I looked over at someone in the office – I won’t say who it was – and they gave me a look that said, ‘don’t leave the tape with him, whatever you do’. So I took the tape back and walked out.” When I ask him if he looks back on this as a missed opportunity, his response is pragmatic: “I’m not saying I could have been part of history. I could have been there, but now I’m here. I found my way back.”

After this, Moss threw himself into Chicago’s party scene – as both a promoter and a dancer – and for a while more or less gave up on production. “I started doing events, and I was mixing with people from different cultural backgrounds.” But life away from home was tough: “There were times I slept on the street for three or four days on end, slept on the beach or between buildings… but I kept going to the parties and kept involved with the scene.” Moss eventually became close friends with Poindexter – “it was nice to have someone older in my life who cared” – and began helping out as a “foot soldier” at parties put on by the likes of Armando, Terry Hunter, Roy Davis Jnr and Felix Da Housecat. “They needed someone on the street, and I was always out there with the youth getting the word out. I could get a couple of dollars in my pocket, get into the party for free and maybe get some free pizzas.”

He also began putting on his own Liquid Love events at the legendary Powerplant. “I would go wherever the music was,” he continues. “I was trying to dance away my frustrations (and) whatever was happening in my life – it was my escape.” Through the party circuit he got to know a multimedia sound artist named Jason and, inspired by the likes of Kate Bush, began bringing avant garde sensibilities to his dancing. “I was captivated by other forms of dance, so I took art house dance techniques to the parties I’d go to. People would see me and my friends as these cool freaks, doing modern art stuff while Lil Louis was DJing at the Bismark. We’d dress up and do performance pieces. We were really trying to be free.” His growing network of musical connections meant he began spending more time in studios, initially as a way to get out of the elements. “I would dabble with stuff here and there, and usually leave it and never think about putting my name on it or asking to release it under my name. There are a lot of cats who simply did it because it was fun.”

With the money he made from parties, Moss enrolled in university. A dedicated people watcher, he began to study cultural anthropology and ethnographic film studies. In addition to the education he received, university also gave Moss an enlightened view of music coming from outside Chicago, with international students turning him onto Warp Records’ early output and Detroit techno. Importantly, as a student he also had access to the college radio station WNUR. Simply by showing an interest (“sometimes other hosts wouldn’t even show up, so I’d be left in charge”) he was given his own show: Jack-FM lasted three years and put Hieroglyphic Being on the musical map. “I did a lot of different stuff to understand the culture itself,” he explains. “I was dancing, putting on parties, playing on the radio, promoting, making flyers, networking, and from there, I’d go to labels and get promos for my show. I’d go to Cajual, Guidance or whoever, and I started to see the office structure and how it worked from within.”

With the money he made from parties, Moss enrolled in university. A dedicated people watcher, he began to study cultural anthropology and ethnographic film studies. In addition to the education he received, university also gave Moss an enlightened view of music coming from outside Chicago, with international students turning him onto Warp Records’ early output and Detroit techno. Importantly, as a student he also had access to the college radio station WNUR. Simply by showing an interest (“sometimes other hosts wouldn’t even show up, so I’d be left in charge”) he was given his own show: Jack-FM lasted three years and put Hieroglyphic Being on the musical map. “I did a lot of different stuff to understand the culture itself,” he explains. “I was dancing, putting on parties, playing on the radio, promoting, making flyers, networking, and from there, I’d go to labels and get promos for my show. I’d go to Cajual, Guidance or whoever, and I started to see the office structure and how it worked from within.”

Having spent some time away from the party scene immersing himself in his studies, Moss got back into putting on parties around 1992. By now there was a whole new generation of people running Chicago’s night life. “People were familiar with me but I had to go back and get reacquainted,” he says. His way of re-earning his stripes belied a shrewd business nous: “I would stand at the front of a cool after-hours party, just by the entrance, and hang out. People would come and see me at the front door and think I was associated with the party. No-one really knew me, but they assumed I must be important because they would see me at these cool spots. In hindsight, it was very Machiavellian,” he laughs.

Around this time he was introduced to Chicago house legend Adonis through a mutual friend; the producer, along with Poindexter, became a guiding light to a young Moss. “I would always see him at parties, he was the man. Seeing Adonis in the late 80s was like seeing Madonna. But we got talking and we became close – I could talk to him about everything in life, not just music.” Meanwhile Moss began using Jack-FM as a conduit through which to broadcast his own musical productions. He started playing demos on air under the pretence they were anonymous white labels; sure enough, there was soon a clamour of interest from attentive listeners. “I would make stuff in my dorm room and take it down to the station and play it on the air,” he says. “I was keeping things low key for years. Eventually a few people found out about it and they said they’d keep quiet if I gave them a cassette to play out!” Moss then began selling demo cassettes from his backpack outside parties. “I’d hang around the exits when the parties were finishing and say ‘hey, this sounds like Richie Hawtin, this sounds like Dan Bell, buy this for 6 bucks’. I was lying my ass off, but I figured that the music was good enough that even when they realised it didn’t sound like Hawtin, they would still enjoy it.”

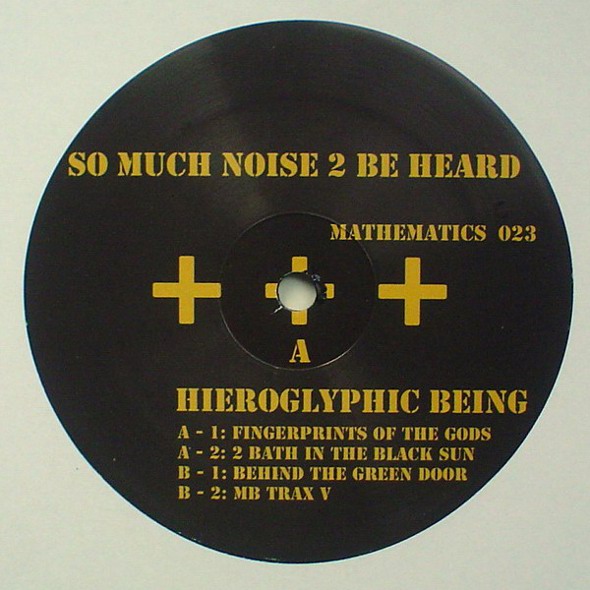

In 1996, inspired by the interest in his cassette ‘white labels’, Moss launched Mathematics Records. He got a P&D deal after seeing an ad in the back of a magazine – “they were like running water at the time,” he recalls – and some name dropping of his high profile friends Adonis and Poindexter quickly garnered interest from the UK. He was sent a box of records as payment for his first release in 1996; he tried to sell them to record shops in Chicago but quickly hit a brick wall. “Everybody was recording at professional studio quality, and getting stuff mastered and mixed a certain way. I had no idea about the production process. I could barely even give that record away,” he recalls.

“My philosophy is, for me to put your music out, your shit has to be so dope it makes me mad as hell because I can’t make it. That’s how I feel; I’m so pissed off I’m going to put some resources into putting this record out until I learn how to do what you’ve done”

Soon enough however, the interest started growing, with further Moss material released on 6277, Spectral Sound, Klang and DJ Hell’s Gigolo imprint. But it was not all plain sailing, and soon Moss found himself homeless for a second time. “Certain things went bad and I had to start fresh,” he explains. “I stayed on a friend’s couch and worked my way back up.” Within two years Moss had his life back on track; and it’s here that the evolution of Mathematics began to take shape. “Life was saying, I’m giving you a second chance – don’t fuck it up.” This time Moss threw himself into releasing records. Although Chicago’s music scene was going through another stage of transition, Mathematics soon established itself as a respected outlet, with Berlin outlet Hardwax among those to support the label in its infancy.

Slowly a stable of Mathematics artists began to form – heavyweight contributions from the likes of Lil’ Louis and Poindexter set the label on its way, before Moss cast his A&R eye to Europe and began snapping up the likes of Simoncino, Marcello Napoletano, John Heckle and Aster. “My philosophy is, for me to put your music out, your shit has to be so dope it makes me mad as hell because I can’t make it. That’s how I feel; I’m so pissed off I’m going to put some resources into putting this record out until I learn how to do what you’ve done,” he laughs, before adding seriously: “I felt it was time for me to give back to others. I know how hard it is to get a hand up – not a hand out – in the industry. If there are people who I feel are on the same wavelength as artists I’ll try to help them get their foot in the door. You don’t see many older artists reaching out to the younger ones – there’s this idea of a rite of passage.”

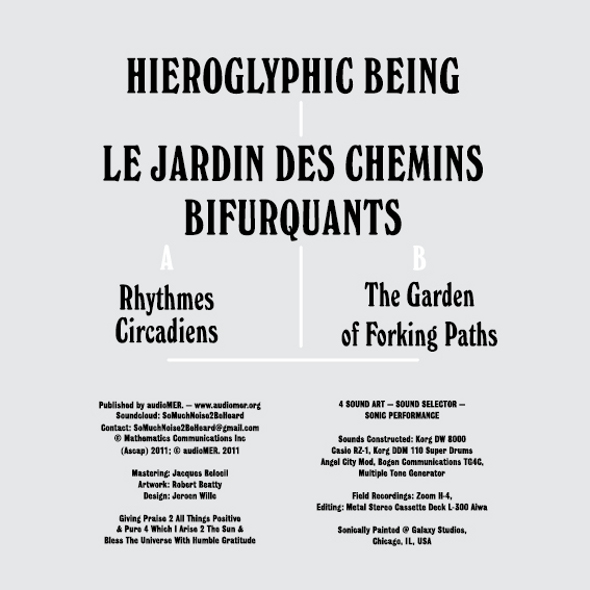

But it’s Moss’s own productions that have formed the backbone of Mathematics: the sound of Hieroglyphic Being is singular, confronting, and often on the verge of derailment. “Life influences my creativity,” he explains. “It’s my DNA, my psyche, my structure. I am the type of individual who doesn’t perceive life as always pretty – I have always seen things close to a fringe or dirty aesthetic. The more esoteric, bugged out stuff sticks with me because of what I experienced growing up. My creativity keeps me from losing my damn mind.”

But it’s Moss’s own productions that have formed the backbone of Mathematics: the sound of Hieroglyphic Being is singular, confronting, and often on the verge of derailment. “Life influences my creativity,” he explains. “It’s my DNA, my psyche, my structure. I am the type of individual who doesn’t perceive life as always pretty – I have always seen things close to a fringe or dirty aesthetic. The more esoteric, bugged out stuff sticks with me because of what I experienced growing up. My creativity keeps me from losing my damn mind.”

While the story of Jamal Moss is hardly a rags-to-riches tale, it’s clear there’s a wizened sense of purpose that informs his life decisions these days. Life’s most fascinating people are invariably flawed, and Moss admits he’s learned many of life’s lessons the hard way. “I have done things half-assed before, I’ve put out music that perhaps I shouldn’t,” he says. “I know now that does more harm than good (because) eventually people will stop knocking at my door. These days I try to do things right – I want to build a better life and sense of continuity for myself and everyone on my label.”

His recent performance at the Barbican, one of London’s most respected venues for visual and performance art, saw him warm up for the Sun Ra Arkestra. Comparisons with Sun Ra, a musical visionary with close ties to Chicago, are there to be made – both the Hieroglyphic Being and The Sun God monikers are direct references to Sun Ra, and Moss frequently cites him as an influence, but when I ask if he’s comfortable with the “afro futurist” term that he’s often labelled with, his reply implies a gentle rebuke. “It’s not a tag I’m particularly comfortable with,” he says. “After all, what if I was Mexican; would I be a Mayan futurist or an Aztec futurist? It’s almost like a polite kind of racism.” His Royal Albert Hall gig was held a week after our interview took place at the storied venue’s humble Elgar Room, a sit-down affair hosted by Wire Magazine. He began his performance by announcing to the crowd: “Nobody’s ears will bleed tonight, but your hearts will be filled with harmonics”, before launching into a set that merged gentle droplets of sound with beats coaxed out of his drum machine. Those expecting an hour of distorted electronics were no doubt surprised, but if there’s one thing we should know about Moss by now, it’s to expect the unexpected.

Words by Aaron Coultate

Photos by Gavin Mecaniques