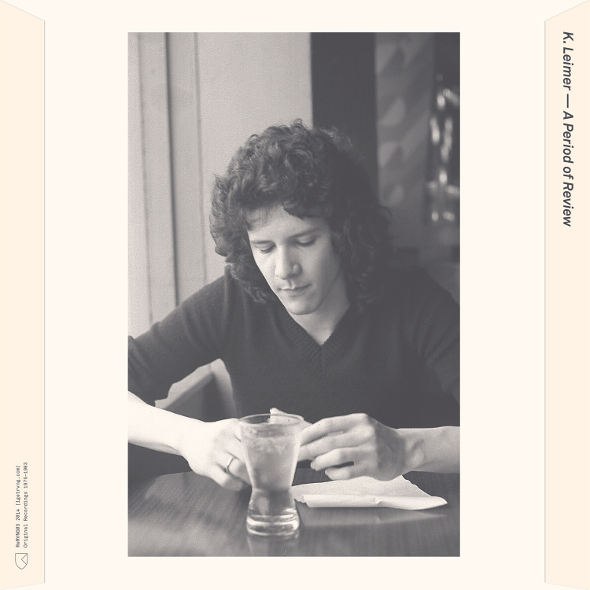

Explanation of Terms: An interview with Kerry Leimer

Fresh from being the subject of an illuminating retrospective courtesy of RVNG Intl, Seattle-based experimental musician Kerry Leimer speaks to Matt Anniss.

Kerry Leimer was enjoying his retirement on Maui – “a safe distance from all the golf courses”, he jokes – when an email came through from Greg Davis at Autumn Records regarding a proposed release of what he calls “orphaned” material he’d recorded during the 1970s.

“Greg had re-mastered and reissued a cassette of mine called Music for Land and Water,” the 59 year-old explains via email. “He wanted to follow up with a similar treatment for another cassette of orphaned tracks titled Installation View. The scope grew due to the volume of early, unreleased material, so he contacted Matt at RVNG and Matt chose to take it on.”

The result is A Period of Review, a detailed compendium of previously unheard material recorded during Leimer’s days as one of ambient music’s most unheralded explorers. While Leimer’s stock has risen a little in recent times – due, partly, to increased interest in electronic experimentation from the early years of the sound in the 1960s and ‘70s – his early work largely remains a mystery to all but the most dusty-fingered crate-diggers. This is perhaps unsurprising, though, when you consider the relative paucity of his releases during the era covered by A Period of Review; between 1975 and 1983, he released just five albums, most of which were released on his own obscure, Seattle-based imprint Palace of Lights. While it’s possible to draw comparisons with the early work of Brian Eno, Robert Fripp, Terry Riley, Stockhausen, John Cage and Steve Reich – as well as new age, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, Erik Satie and, despite his claims of having no interest in the genre, dub – Leimer never enjoyed the acclaim or commercial success of his peers.  The issue of A Period of Review, then, is something of a boon for all those – this writer included – who were unaware of his sparse contributions to the development of ambient music. Leimer himself admits to being surprised at the interest in his early experiments. “It’s always a surprise,” he writes, “especially to get such interest in such early and naïve music. I’m not much of an archivist: I tend to keep moving to the next idea, so my back catalogue is pretty much unavailable to me. Thankfully my long time friend and collaborator Robert Carlberg had actually kept many of the original tapes. He got together with Matt at RVNG and began a nearly year-long recovery and repair project, with each newly uncovered collection of tracks shaping the scale and direction that A Period of Review finally took.”

The issue of A Period of Review, then, is something of a boon for all those – this writer included – who were unaware of his sparse contributions to the development of ambient music. Leimer himself admits to being surprised at the interest in his early experiments. “It’s always a surprise,” he writes, “especially to get such interest in such early and naïve music. I’m not much of an archivist: I tend to keep moving to the next idea, so my back catalogue is pretty much unavailable to me. Thankfully my long time friend and collaborator Robert Carlberg had actually kept many of the original tapes. He got together with Matt at RVNG and began a nearly year-long recovery and repair project, with each newly uncovered collection of tracks shaping the scale and direction that A Period of Review finally took.”

Leimer deliberately took a back seat when it came to selecting the tracks, leaving that to others. He did, though, allow himself a little indulgence, listening afresh to tracks he created, often during intense periods working alone in his Seattle studio, over thirty years ago.

“The process of developing the music has always been more important to me than the outcomes, so only occasionally do I revisit finished music,” he admits. “In this case it was pretty amusing, and the impressions were predictable, ranging from ‘that’s not so bad’ to ‘WTF!’. The memories were quite fond: the equipment failures, the surprise when things work out both technically and musically. Not much has changed in that regard.”

The 30 tracks that make up this richly deserved trawl through Leimer’s archives – a mixture of short sketches, fully-formed mood pieces, odd experiments and quirky bursts of innovative sound design – were selected by RVNG from dusty reel-to-reel tapes containing over 60 tracks. Some never saw the light of day first time round because they didn’t fit in with any particular project, while others were circulated to friends in the form of homemade albums. Some are stunningly picturesque, while others are difficult and nightmarish. By and large, though, they’re rather melodious, something that becomes more surprising when you consider the experimental nature of Leimer’s working method.

During the nine years covered by A Period of Review, the artist-turned-musician had a rudimentary selection of instruments and electronic devices at his disposal, and relied mostly on experimental recording techniques to create his unique, otherworldly sounds.

“The earliest sources included an electric organ, a homemade bass guitar and various wooden and metal objects,” he explains. “Then came an escalating series of Moogs – Micro, Mini and finally the MemoryMoog. That struck me as an under-appreciated synthesizer, sitting as it did on the cusp between analog and digital synthesis and coming perhaps too late when considered beside the then very popular Sequential Circuits Prophet-5.”

“The earliest sources included an electric organ, a homemade bass guitar and various wooden and metal objects,” he explains. “Then came an escalating series of Moogs – Micro, Mini and finally the MemoryMoog. That struck me as an under-appreciated synthesizer, sitting as it did on the cusp between analog and digital synthesis and coming perhaps too late when considered beside the then very popular Sequential Circuits Prophet-5.”

“As far as A Period of Review is concerned, the Moog and an Oberheim module were the principal sources – MiniMoog in particular – with settings recalled via Polariods. To make things simple all the electronic instruments were run straight through the board – few mics and no amps involved. So what you’re hearing is a somewhat atypical sound: direct outputs manipulated with the rudiments of tape direction and speed, radical EQ and too often too much reverb.”

Using this relatively basic set-up forced Leimer to experiment freely, and he would regularly spend hours holed away in the studio creating tracks inspired by happy accidents; a found chord here, a strange tape loop there. “The starting point then might have been a phrase, or something I came across accidentally on the synthesizer,” he recalls. “It might be an extract trapped in a closed loop. When the open loop was in place something might emerge before the tape ran out, and then that would be bounced down to add either repeating or non-repeating parts. The original impetus might never actually be present in the resulting track since I’d then go on to add and subtract, manipulate and process. There are several tracks that worked out this way: eliminating the starting point and setting the additions adrift to flutter on their own. It never became very systematic, but there was always the drive to subvert the equipment, to subvert the audio and trick things into some recognizable order.”

Like many of the experimental electronic pioneers of the period – in particular Stockhausen, Delia Derbyshire, Daphne Oram and John Baker – Leimer was particularly fascinated with the potential of tape loops. In the extensive sleeve notes accompanying A Period of Review, he talks at length about the mesmerising hold they had on him.

“What I found exciting about tape loops was the fact that you’re collaborating with a system rather than an individual,” he asserts. “A system that doesn’t really react as much as simply repeat in the form of an extended decay. So you’re dealing with the initial signal and then some manipulation of that signal, in real time. It results in music that seems immediately comprehensible, more reliant on timbre and generally free of, let’s call it, ostentatious gesture. It’s not music of distraction or necessarily music to be sublimated. In my experience, it encourages a form of concentration that incorporates a lovely, entropic sensibility. It’s fatalistic in the sense that it is intellectually automatic and emotionally elegiacal.”  Leimer was 17 when, as an art student obsessed with Dadaism, surrealism and musique concrète, he decided to start exploring the almost limitless potential of electronic music. At the time, he was not turned on by what was happening around him in Seattle – there was too much prog rock, for starters – but rather cutting edge music from further afield that blurred the boundaries between art and music.

Leimer was 17 when, as an art student obsessed with Dadaism, surrealism and musique concrète, he decided to start exploring the almost limitless potential of electronic music. At the time, he was not turned on by what was happening around him in Seattle – there was too much prog rock, for starters – but rather cutting edge music from further afield that blurred the boundaries between art and music.

“The earliest attractor was Frank Zappa, specifically Lumpy Gravy, an inexplicable early fondness for Mozart’s Requiem – unfinished music is almost always of interest – and then the vast expanse of German experimental and electronic music of the day typified by Harmonia, Neu!, Faust, Cluster and Kraftwerk up to and including Ralf & Florian,” he explains. “Within that context Fripp & Eno’s (No Pussyfooting) proved to be an overwhelming record for me. Perhaps more importantly Eno’s Obscure label was incredibly affecting in its diversity and what proved to be long-term significance on my expectations of music. I found almost all popular music to be uninteresting at best, but the personal astonishment and attraction I felt in hearing David Toop, Max Eastley, Gavin Bryars, Penguin Café and Michael Nyman for the first time initiated a life-long interest in alternative and new music, not to mention the compulsion to try out the ideas those artists engendered on my own.”

For Leimer, music was by and large a solitary pursuit. He had little interest in performing live – “I like to think of music in terms of art rather than entertainment, and so much of live performance strikes me as personality and entertainment-based”, he explains – but was enchanted by the allure of his particularly intense creative process. It was the potential of the studio and what could be achieved with machinery, rather than traditional instruments and musicians, that drove him.

“That’s a very fair assessment,” he admits. “I relied on experimenting as the generative point. Things tended to become self-deterministic, which was the goal. I didn’t want to become a musician in the traditional sense. No technique, no practice, just cultivating an openness to all the accidental chords. The interest for me was artistic expression first and foremost. I doubt that I ever pushed that far enough, but that remains the aim.”

Given his artistic background and lack of musical training – “The absence of training can be as liberating as it can be debilitating,” he admits – it’s perhaps surprising that much of the music on A Period of Review, and on Leimer’s albums from the early 1980s, for that matter, is so richly textured and harmonic. While clearly experimental and leftfield, there’s a grasp of mood and melody that belies its curious construction. It begs the question: was Leimer’s music deeply personal and inspired by his own mental wellbeing?

“I can’t say my music is deeply personal beyond anything that might somehow make it distinct from the music of others,” he retorts. “While I tell myself that the music I pursue now is generally emotionally neutral, I’m always drawn to sad music, to elegy. I heard that quality in early open loop works: the decay, the thinning and collapsing signals, the persistence of what came before. Even now I think I’m primarily interested in sound as sound and music as music, free of metaphor and allegory. Even so, reviewers often write about a sadness and beauty that belies my interest in impartiality.”

Regardless of Leimer’s obsession with musical impartiality, the works showcased on A Period of Review definitely stir emotions. It’s perhaps this, as much as the methods used in their creation, which leaves such a lasting impression. Given their quality – despite the fuzziness of the vintage recordings – it’s even more surprising that Leimer failed to find much of an audience for his music to begin with. He’d been making music for some time before he released his first album under the now familiar K. Leimer alias, the cassette-only Natural History/The Mind & Its Likeness, in 1979. It was only when he took the step of launching the Palace of Lights label later the same year that his reputation spread further than the tiny confines of Seattle’s alternative music scene – a scene that his particular brand of elegiac electronic experimentation barely fit into.

“In Seattle at the time there was OP Magazine, a few bands I found to be interesting – the Blackouts, Young Scientist, 3 Swimmers and the Wipers come to mind – and a few people doing their own thing,” he recalls. “Through the scene I met composer Steve Peters, who I felt was doing some of the most beautiful work then and now, and of course Marc Barreca, who I collaborated with in the group SAVANT. Through Steve, Marc and Robert Carlberg, I was put in touch with others of like or related interest – Steve Fisk, Gregory Taylor, Michael William Gilbert, Roy Finch, Alan Greenberg and Dennis Rea. The scene in Seattle as I knew it was not geographical, small in number, and generally uninterested and unable to connect with the locals that were aspiring to be commercially accepted.”

Many of these artists would join Leimer in releasing material on Palace of Lights, during a freakishly productive period between 1980 and ’83. “The early releases were pretty diverse,” Leimer recalls. “SAVANT’s Neo-Realist (at Risk) was sort of post-rock, Roy Finch’s Fiction Music was electro-pop. Steve Peters’ Regional Zeal was experimental, and Michael William Gilbert’s In The Dreamtime was progressive jazz. It was all quite different. Most of all it was about releasing work by some friends who were pursuing things I thought were great – our own little Obscure Records.”

Despite releasing some fascinating and celebrated music, Palace of Lights stopped releasing music in 1983 as Leimer put his musical output on hold to concentrate on the demands of his day job; running a successful design agency with his wife, Dorothy Cross.

“By that time our design office was taking on clients at an alarming rate,” Leimer remembers. “We drew business from around the US and Canada and so I went with my education and training and put all my time and energy into design. I didn’t consciously put music aside, but the time for it vanished into fulfilling the needs of others, and the experience of such a sustained ramble through commerce and the corporate world eventually confirmed my worst suspicions of that way of being and living.”

“By that time our design office was taking on clients at an alarming rate,” Leimer remembers. “We drew business from around the US and Canada and so I went with my education and training and put all my time and energy into design. I didn’t consciously put music aside, but the time for it vanished into fulfilling the needs of others, and the experience of such a sustained ramble through commerce and the corporate world eventually confirmed my worst suspicions of that way of being and living.”

Happily, as he ambled towards retirement at the turn of the millennium, Leimer decided to start making music again. “It was more like compulsion than choice,” he admits. “Having remained an active listener I was anxious to revisit some old ideas and bash them into some new ideas, using new technology. Of course, the working method is now different. It’s now completely digital, and mostly generated in MIDI. The preoccupations are much more timbral and much less melodic. There’s lots of file shuffling – generating mountains and time and pitch compatible material and then testing juxtapositions, reprocessing, signal erosion, before editing it all down to something comprehensible.”

Since 2002, Leimer has released a steady trickle of albums on the re-born Palace of Lights imprint. As well as his own material – more akin to drone than his melodious older work – there’s been a constant stream of albums from those involved with the label first time around.

“I never lost the interest, it’s just that over the past ten years I’ve had the time again,” he enthuses. “The people who were involved with Palace of Lights first time round are still active in music, so we’ve been able to pick up somewhat where we left off.”

Leimer genuinely seems excited about the prospect of pushing the label forward in coming years, though naturally he has no interest in gaining commercial success or developing beyond its status as an outlet for experimental music by his friends and collaborators. There is, though, plenty of intriguing material in the pipeline.

“After all these years Marc Barreca and I finally completed a genuine collaborative album, Preamo, and Greg Davis is mastering one that I’ve just finished of my own work, The Grey Catalog,” Leimer reveals. “We’re going into manufacturing for Gregory Taylor’s collaboration with Darwin Grosse entitled Tourbillion Solo. And I’m about half way through another project that I hope to complete with Taylor Deupree’s help again. Oh, and there’s also the SAVANT archive project with RVNG, so there’s plenty more to come.”

Interview by Matt Anniss

K. Leimer’s A Period of Review (Original Recordings: 1975-1983) is out now on RVNG INTL. You can find out more about Palace of Lights at www.palaceoflights.com