DJ Nature: Necessary Ruffness

There aren’t many artists who manage to drop their project just as it’s taking off, only to return with the same venture twenty years later and find success with a completely new audience. It perhaps speaks volumes for the timeless quality of proper house music that it hasn’t necessarily needed to change in that time to still sound strong amidst more recent developments in dance music. Yet when it comes to the music of Milo Johnson, there’s an overwhelming feeling that his music stood apart from the crowd even back in 1991 when he was issuing a few New York-flavoured house gems under the name of Nature Boy.

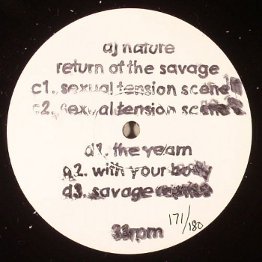

It can’t be overlooked that Milo’s roots go back further than that, to a pivotal time in the history of Bristol music as part of the fabled Wild Bunch soundsystem, but a move to New York in 1989 gave rise to the Nature Boy project, which has been revived in the past couple of years as DJ Nature, largely orbiting around releases on highly-regarded label Golf Channel. “I’ve always wanted to get back to doing this type of thing,” says Milo as we speak ahead of the release of his Return Of The Savage double pack. “It’s just that it’s a bit tough calling yourself Nature Boy when you’re 50, so I just altered it.”

Listening to the DJ Nature 12”s that have been issued since 2010 and then tracing back to the original Nature Boy releases, there is an undeniable correlation between the music despite the time that has passed in between. More than anything, a soulfulness permeates the tracks which comes from the deft juxtaposition of samples. Whether it be a haunting string hook or a weighty vocal lick, an indefinable atmosphere ties the pumping early 90s grit of Nature Boy to the more elegiac tones of DJ Nature.

“With a lot of the initial stuff I put out as DJ Nature,” explains Milo, “it’s just old deep Nature Boy stuff. I was tidying and I found a box of old floppy disks, so I put them into the S950. I heard all these ideas, loops and samples and shit that I never really got to finish, so I decided to bang out a couple of those to see what I came up with.”

There’s undoubtedly a greater production value in the new material which belies the years Milo has spent pursuing other production work independent of his house music output, but the DJ Nature era heralds a time when he is dedicating more of his energy to his love of 4/4 groove. “I’ve never just submerged myself into music full time without doing another job,” he reveals. “It’s always been something I was really scared to do to be honest with you, ‘cause I really didn’t want to have to conform to what was popular in order to pay the rent.”

It doesn’t take long to understand that there’s a hint of resistance about Milo and his music, and as such it’s no surprise to learn that conformity isn’t an option for him. It’s a theme that gets raised throughout Milo’s house output with the Necessary Ruffness releases, both back in 1993 as Nature Boy and in 2010 as DJ Nature, hailing his belief in an unpolished approach to production that brings its own kind of character to the music.

“The people who influenced me in terms of my Nature Boy project are people like Todd Terry and especially Patrick Adams because they were raw,” Milo enthuses. “It was the rough productions that stood out. Adams had the elements in there like strings, relatively well played bass, but you could tell it was done in some rugged studio, and that really goes back to what the Bristol sound is. It’s just something that I’ve always gravitated towards in terms of music.”

That aforementioned indefinable atmosphere in Milo’s house cuts certainly shares the same smoky air as the legacy of Bristol music. After all, when he was active in some of the defining years of the city’s musical heritage, there was always going to be a tattoo on his sonic DNA that would shine through whatever path he had chosen to follow.

“It’s not something I think about often,” Milo says of the impact the Wild Bunch days have had on the music he makes now, “but when I reflect sometimes, especially when I do something I think is really good, I know where that comes from. All the best tunes I was listening to back in ‘79, all the early punk stuff; that ethic, that energy is pretty much where I’m coming from, and that was predominantly that Bristol sound in the first place.”

There’s no denying the link between the DIY ethos of the punk and post-punk era and the democratisation of production that took place when cheap electronic equipment hit the market. As was customary for the time, Milo’s means of beat-making were humble; a situation which no doubt lent itself to his quest for sonic grit.

“All I had was a little four-track mixer board and real primitive stuff,” he remembers. “When I first started buying house stuff back in ‘84, ‘85, it was all your Farley shit right? It was rough and rugged, and what I wanted to do when I came out in ‘91 was bring something to house music that was like what Wu Tang did to hip-hop. When they came out it was all glossy videos – they took it back to grimy production, something you’d hear in a club and go “what the hell is that”? not because it’s original but because it stands out against all the gloss.”

After a few years with a steady stream of releases on his own and other people’s imprints, Milo shelved the Nature project indefinitely. You can’t help but wonder why, when his productions were tapping into a fertile creative vein and his profile was on the up, Milo didn’t want to dive full time into the Nature Boy project back in the early nineties. After all he had certainly found himself at a very good time to be a house music producer in New York.

“The funny thing is I stopped doing the Nature Boy stuff right when it was going well,” he recalls. “I’m not saying I was doing some flippin’ Todd Terry type numbers, but the star was rising, and I was making good contacts with the guys at Nu Groove and E-Legal Records, so I had outlets, but my kids were born in ‘92 and ‘94 so I really had to prioritise.”

Considering the resurgence in interest the Nu Groove pantheon in particular has attracted in recent time, it’s surprising to think that Milo had their ear at the time but chose not to push the project further. However where many might seek to promote themselves mercilessly and network all over the city, Milo’s approach to New York was a more casual one from the moment he arrived, starting from scratch in 1989.

“When I look back on it and see where me and the missus came to be, it’s crazy,” Milo recollects. “New York wasn’t a clean place, it was rough. I didn’t have any links at all, but the reason I moved to New York is that I didn’t really think I would have been able to do the music I wanted to do in England. Nature Boy in New York wasn’t doing that much but it was good enough for me.”

However his own music wasn’t the sole motivation behind the move across the Atlantic. Through a friend of his sisters on the other side of the world, Milo was quick to move on an opportunity that led to seven years worth of solid work with some of the key figures of the New York house scene.

“I was exporting records to a Japanese store, so I’d be shipping old shit, used records and new releases, from ‘89 ‘til round about ’96,” Milo reveals. “In the golden age I was really on top of all the new house stuff and providing music to the most demanding market there was at that point in time.”

If anyone would look for a way to get ingratiated with the figureheads of the scene, working directly with the labels and artists was certainly a good way to do it. While he was dealing with some of the big hitters in the city, after a certain amount of time Milo retreated from getting too involved in the nightlife of New York.

“Frank Mendez (head of Nu Groove Records) would take me over to see Tony Humphries at Zanzibar in New Jersey,” he recounts, “and that was basically the only time I used to go out back then. Even to this day I really don’t venture outside of my house at all. I used to go out say up until ‘96, and then I stopped going to clubs altogether pretty much.” With his regular haunts in the early part of his New York life being the Sound Factory and Red Zone, at a time when house music was on a rapid ascent, Milo got his fill of the city’s party scene. “Early days were better days,” he states. “If I had gotten stuck right into the house music scene I guess it would have given me a better edge for the distribution ways but I’m just not that type of person.”

It’s not to say that Milo wasn’t gigging at all. When he wasn’t mixing for his own satisfaction in his room, he travelled to Japan to play odd gigs, while in New York he sometimes hooked up with the likes of lauded hip-hop producer Salaam Remi. It was the No Ordinary Monkey parties around the turn of the century that forged the connection Milo has with Phil South, the man behind Golf Channel. From a loft in Manhattan’s meat packing district to the Lower East Side, Milo got to experience some high grade gigs even while unconsciously sowing the seeds for a relationship that would prove pivotal to the success of DJ Nature.

Still though, Milo’s cautious ways about the social aspect of house music have fed through to today. Even while he has dedicated himself full time to DJ Nature, he exercises a shrewd judgement when venturing out.

“I do turn gigs down,” Milo explains, “even though I’m not inundated with requests, but sometimes it’s not really worth it for me to sacrifice sound quality for money, ‘cause I won’t be able to get my message across in the way that I want to.”

“I’ve never been one to say ‘I want to play in big clubs’,” he adds. “That’s not my deal. I want to play in clubs that fit in the amount of people that need to see me in that particular area, and the system needs to be a decent system. I’ve got to be realistic and say that not every club is going sound like Plastic People, even though I wish they could, but I have to make sure that the majority of times I play are close to that.”

Having played with Floating Points as part of his residency at the East London basement mecca, Milo now has a high benchmark against which to measure future bookings. Between word of mouth and a persistent agent hustling for decent sound, he does what he can to avoid duff gigs.

Somewhat surprisingly, considering his history in the wax trade and a DJ career stretching back some thirty years, if you head out to catch Milo playing these days, you may be a little surprised at his thoroughly modern methods. “I pretty much play with Traktor right now,” he admits, “even though I’ve got untold vinyl records. I would prefer to play vinyl, but I went to play in London one time, and American Airlines lost half my records. I had to keep going back and forth to Heathrow airport for the next couple of days waiting for them to come in on the next flight, and it never came. I was watching the fucking luggage rack go round for two days, and I just said to myself, ‘I ain’t never going through that again’.”

Fortunately, Milo’s wife managed to retrieve the records back at JFK, despite the airlines constant insistence that the records would be on the “next flight”. It’s an understandable reaction to want to protect your most treasured tunes, but the transition to digital still didn’t come easily for Milo.

“I was so against that shit, you don’t even know,” he affirms. “I couldn’t think of anything more soulless, but I love my vinyl so much, that I am not willing to have it lost or stolen by anybody. I’m not one of those cats who would put everything on digital and sell my records. My room and my storage space is just choc full of records, but I’m not losing it for anything.”

In truth, while vinyl aficionados may well baulk at the prospect of switching to digital, or very well seeing someone else do so, the decision once again highlights Milo’s careful approach to his craft. It would be an interesting poser to put to the scores of DJs who have ever lost their records on the road.

“You get a lot of these guys who are really pro vinyl and they hate digital,” Milo continues, putting forth his perspective on the timeless debate. “My theory is that you can be extreme in both senses. You could give the same 100 records to two DJs, and Tony Humphries will play 100 records a different way from say “Little” Louie Vega, and I think the same works for digital as well. The soul is from within, and if you’re talking about mixing stuff back to back then fine, anybody can be a DJ, but that’s not what I do.”

Milo’s approach clearly won’t see him swinging with the biggest players in the game, but the course of his career carries with it a reassurance that there’s no danger of him compromising the quality of his work to make a quick buck. The humble approach in music can quite often be the purest one, free of pretention and loaded with soul.

“As far as I know I’m going to be doing this ‘til the day I die,” Milo declares, contemplating how long this current spell of Nature productions might last. “Come twenty years down the road I can probably see another reincarnation of this shit in some form.” It’s an exciting prospect, considering the smooth evolution of the project from its rough and ready four track roots. Who knows how DJ Nature will be sounding in twenty years time? If the last twenty years are anything to go by, the transition should be seamless.

Oli Warwick