I Was There – a lifetime of Aphex Twin shows

Three decades of Aphex in action

I can remember precisely where and when I was when I realised Aphex Twin was going to be a star. It was at the door of Manchester Academy, in the early hours of October 10, 1993 and it had been a long night. The main attraction at the Megadog-hosted event had been The Grid, with the excellent – but ultimately forgotten – sprawling rap-rock collective Senser opening, during the week they would appear on the NME’s front cover for the first (and last) time.

Occupying the graveyard slot, coming on sometime around 2am, was Aphex Twin. It wasn’t my first brush with Richard James, who at the time best known for his crusty-baiting ‘Digeridoo’ single for R&S, alongside diverse work under various names as part of Warp, from the pounding ‘Quoth’ as Polygon Window to the sweet Top 20-charting standalone single ‘On’.

I’d first seen him in person at the Deptford Free festival, back in the summer of 1992, where he’d gracefully joined the dots between the techno bliss of Orbital and the anvil brutality of industrial headliners Test Dept. In April 1993 I’d seen him deliver a set of bubbling, sense-defying ambient music between psyche rockers Levitation and Spiritualized at Hackney Empire and then supporting The Orb at Brixton Academy. His live show back then was just that – very much live, with James very visible centre stage and hands on, controlling big banks of equipment and delivering vicious salvos of techno that would often include material from his various aliases.

What made the Manchester show so special was more to do with the conversation I’d had outside than the music inside. Sharing a cigarette with a local punter who’d come down just to see Aphex, I realised he was fascinated by James as a person as much as a musician. He told me all the myths surrounding him – how he stayed awake a week at a time and wrote his music while lucid dreaming, how he’d built all his own equipment by hand and so on. In a genre that was dismissed at the time as ‘faceless techno bollocks’, this personality had left a serious impression.

This would ultimately become the key to success for Aphex, especially after the critical backlash that followed the release of the ultra-minimal ambience of ‘Selected Ambient Works 2’ in 1994, despite it landing at number 11 in the UK album charts. I Care Because You Do, the following year, came with a garish, nightmarish portrait of James on its cover and in what is surely one of the most disturbing promotional ideas ever, some copies were delivered to journalists with strands of red pubic hair stuck to them. It was the ultimate mocking of the personality-above-music trivia that the weekly music press stuck to through the Britpop years and which ultimately led to its eventual decline and extinction. It was an idea that James picked up and ran with, from the equally scary caricature on the cover of his next album Richard D James to the feral Aphex-faced children running amok in the ‘Come To Daddy’ video and the even more grossed out faces in the ‘Windowlicker’ promo. There were many insults you could potentially sling at Aphex, but faceless was not one of them.

The irony was, for the few of us writers lucky enough to meet him, Richard James was anything but sinister. “I’m only terrifying to people who are nasty to me” he once told The Guardian’s Paul Lester, which might or might not explain the state that Madonna left his Braindance club night in. She was being rushed away literally feet from my face by a team of personal bouncers as I arrived for the weekly night of Rephlex artists at the Sound Shaft, the tiny annex at the rear of London’s Heaven nightclub. She’d apparently descended on the night unannounced and buttonholed James to do a remix for her. His suggestion had apparently been that he’d do it if she generated some sounds to work with, using a certain vibrating piece of erm, home entertainment equipment.

I was privileged to spend an hour or so in the garden of a Kensington Hotel the company of James and Philip Glass around the time that their collaborative ‘Donkey Rhubarb’ EP was released. I recall following thirty or so yards behind him as we arrived, him with his battered green Rephlex bag slung around his shoulder, and seeing him being stopped for an autograph by a passing fan, and he seemed the epitome of charm. In the interview he was polite and surprisingly quietly spoken in a gentle accent that encompassed both his Cornish roots and his London home. You might even say normal – he certainly appeared that way on the occasions I’d spot him wandering around Elephant and Castle, again with that Rephlex bag, having moved into a disused bank off Newington Causeway. Yes, that particular myth was definitely true. Despite the fact he’d recently reportedly scooped close to a million quid with the licensing of tracks to a handful of adverts, the public phone box outside Central Heights flats seemed to be a particular favourite spot of his.

It was during these latter 90s years that James hit a peak of live performance that he’d never reach again. It was his friend from Cornwall, Luke Vibert, who switched him onto the splintered breakbeats of jungle. Vibert recalls Rephlex co-owner Grant Claridge-Mitchell and James being initially dismissive of it, still preferring Chicago house and classic acid, but the penny soon dropped with James.

Indeed, it was at a Vibert-hosted night at The Blue Note in Hoxton in 1996 where James revealed his new, hyper-programmed live show, although the two ‘Hangable Auto Bulb’ EPs had pointed the way forward. Arriving through the basement’s double doors with his set already in progress, I was greeted by the site of 200 or so people looking more astonished and dumfounded than any audience I’d seen before or since. Tune of the night was undoubtedly ‘Bucephalus Bouncing Ball’ – an eventual B-side to ‘Come To Daddy’ and later included on the soundtrack to ‘The Life of Pi’ – with its bouncing ball breakdown. Jaws were still being picked up off the floor ten minutes later.

Later that year I witnessed him taking a souped up version of the same show to festivals from Switzerland to Phoenix and Tribal Gathering, accompanied by fighting giant orange teddy bears and, at Tribal Gathering, muscle flexing bikini clad female body builders. Using a trick that, legend has it, was also utilised at the Nuremburg Rallies, he played roaring crowd noise at the end of each track, tricking people in neighbouring areas into coming to check out whatever it was that was really going off in his tent.

The following year, he crowned off the month of October, that started with the release and then subsequent chart placing of ‘Come To Daddy’, with a Halloween show in London. The venue? Only the Clink Prison in Southwark, home to unspeakable acts of cruelty since 1144 – as well a venue for some of the first acid house parties the capital ever saw. He would appear on stage but spent the set, as was his wont by this stage, lying down inside what fans dubbed his Wendy House.

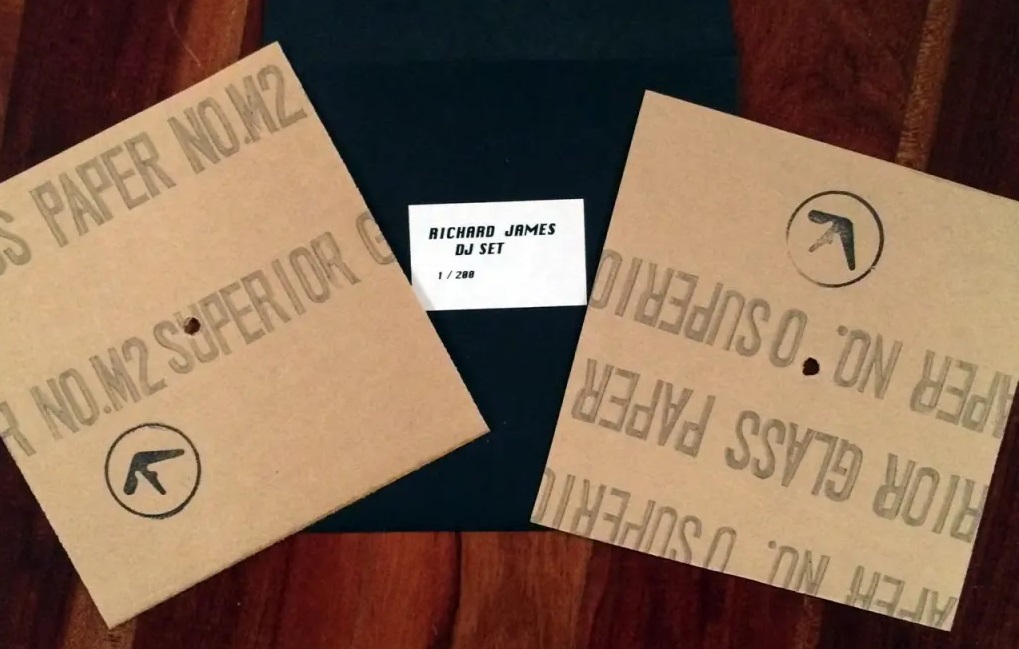

Since then, and certainly during the last decade, Aphex shows have tended to be DJ sets rather than strictly James-only affairs, and if the set captured on YouTube from the Best Kept Secret Festival in Netherlands a couple of months back is anything to go on, his appearance at Field Day this weekend will be along similar lines, if accompanied by the kind of spectacular production that DJ sets never, ever get treated to. Not that his James’ skills as a DJ should be sniffed at either. He may twice – another myth that is true – have used sandpaper discs as records at Disobey nights (run by Wire/Mute man Bruce Gilbert) but as a veteran of the decks even before he’d made a record, he’s more than capable of delivering the goods, fusing everything from ancient acid and hardcore to the latest bass experiments.

That said, be prepared for the occasional mischievous spanner being thrown into the works. At a Warp night sometime around the turn of the millennium – it may well have been at one of their tenth anniversary nights at Brick Lane Brewery in 1999 with Squarepusher, Autechre, Boards of Canada and the late Mira Calix – he played the whole of ‘Sabotage’ by the Beastie Boys backwards. Take it from us – you’ve never heard anything so satanic in all your lives. Good work Aphex!

Ben Willmott