Richard Sen early 90s Brit scene comp interview: “What was happening back then is all like a dream now”

The Bronx Dog digs up an alternate history of the UK’s early techno and rave scene

In recent years, we’ve been treated to numerous crate-digging compilations focused on Britain’s acid house and rave era heritage, alongside countless reissues of obscure, overlooked and lesser-known UK house, techno and breakbeat hardcore records from the late 1980s and early 90s.

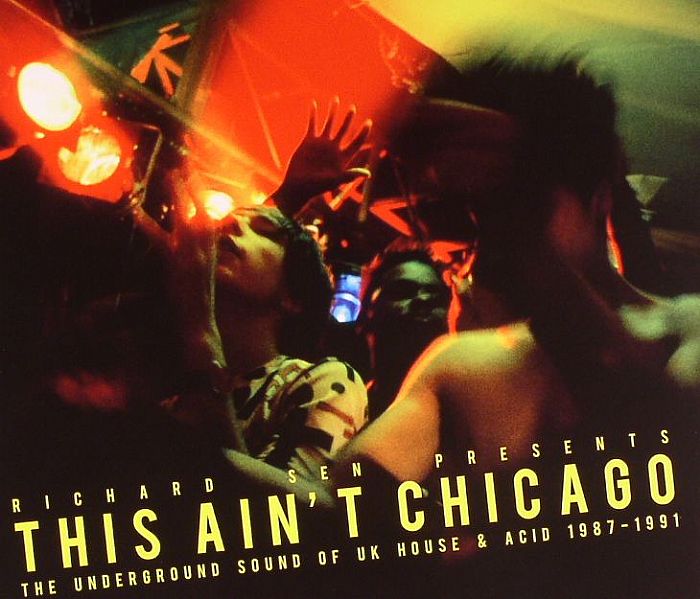

It’s a positive development and one welcomed by Richard Sen – a long-serving DJ, producer and record collector best-known for being part of late-90s breakbeat outfit Bronx Dogs and noughties dark disco innovators Padded Cell. Back in 2012, Sen released an indispensable survey of early UK house, techno and acid, This Ain’t Chicago, via Strut Records. It was met with widespread acclaim, with critics lauding his attempts to showcase early examples of British dance music trying to find its own voice.

“Most people didn’t know those records and I thought they needed to be heard,” Sen explains. “There was definitely a ‘gap in knowledge’, as academics would say. I looked up to all the artists and labels featured on This Ain’t Chicago, and I couldn’t believe that nobody had done a compilation looking specifically at what I thought was an overlooked and ignored British movement.”

Sen was not alone in being frustrated with what was, for a long period, a blind spot in UK dance music history, but he was amongst the first to highlight issues of erasure. The narratives of British dance music from the period had previously been set – Balearic and the second summer of love of 1988-89, followed by the later emergence of hardcore and jungle, with little else discussed.

“For a long time, many people looked down on those records and those early house and techno records from Britain because they weren’t American, but they have their own style and sound,” Sen reflects. “A lot of the artists associated with that scene were from the black community and they had been written out of the history – everything was so focused on Danny Rampling, Terry Farley and Andrew Weatherall. For whatever reason, people like Rhythm Doctor, Richie Fingers, Kid Batchelor, Eddie Richards, Colin Faver and Colin Dale are not seen as being part of the UK legacy of acid house, so I wanted to big them up more.”

Sen started his musical journey during the 1980, first as a hip-hop loving graffiti writer in his home city of London (he spent a short period in prison for his “graff” exploits in 1989), then as a convert to the emerging acid house and Balearic movements. “I was robbed at a Public Enemy gig, and that pushed me away from hip-hop a bit,” he recalls. “Then I went to clubs with my mates and took my first Ecstasy tablet. That changed everything. I went from being robbed to being hugged by strangers! It was a no-brainer.”

Suitably inspired, Sen threw himself into the emerging culture, becoming a familiar face on dancefloors of legendary London clubs – the Astoria, Heaven and the Camden Palace – while also travelling out to the raves that popped up on sites close to the M25. He was inspired not just by house music and emerging forms of techno, but also the eclectic Balearic sound. Andrew Weatherall (who later championed Sen’s solo productions and remixes, something that’s a still blows his mind), Pete Tong and Nicky Holloway were amongst his favourite DJs at the time, though he also cites the Eddie Richards, Colin Faver, Matthew B and Colin Dale as influences.

He remembers attending two of Holloway’s Kaos Weekenders, which took place at Pontins in Great Yarmouth; both were important formative clubbing experiences. “It was good because Nicky had booked a broad range of DJs,” Sen reminisces. “There were basically two camps: the Shoom and Boy’s Own lot in one room, and a sort of Clink Street-influenced room. That was blacker and more working-class, with music that was darker and heavier. I just kept moving between the two rooms.”

He was inspired enough to start acquiring more and more records, while setting his sights on becoming a DJ – or at least DJing in public regularly. He managed to bag himself a slot warming up at a Sunday party at Busby’s, a few doors down from the Astoria, for the Crazy Club crew. That led to residencies at both of those venues (he was stationed in the Astoria’s bar, playing house and Balearic beats as an alternative to the heavy techno and early breakbeat hardcore dominating the main room), as well as semi-regular appearances at the Limelight Club on Sundays.

“I played a fair bit in 89-90, but after that it was more sporadic as I wasn’t a name,” Sen says. “I was just doing underground parties and random, sporadic stuff until I started making music in the late 90s.”

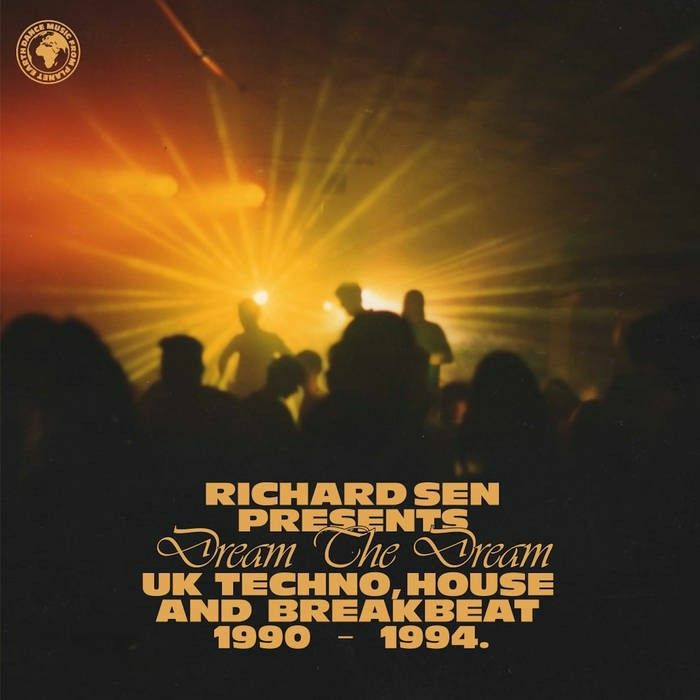

He never stopped buying records, though, and because of that owns a remarkable collection of dance music from the 1980s and 90s – including a wealth of obscurities, slept-on-gems and criminally overlooked gems. It’s that collection that he’s mined once more for his new compilation, Dream The Dream: UK Techno, House and Breakbeat 1990-94, which marks the debut of Ransom Note Records new sublabel, Dance Music From Planet Earth.

“A few years ago, I mentioned to Wil Troup at Ransom Note that I’d like to do a follow-up to This Ain’t Chicago, maybe looking more at British stuff rooted in techno and in a slightly later time period,” Sen remembers. “It was just an idea for ages, but then last year Wil came to me and said he thought the time was right.”

While a different beast to This Ain’t Chicago, Dream The Dream is in many ways a continuation of the same narrative. Packed full of genuinely little-known tracks, the compilation giddily flits between trancey, breakbeat-driven gems (Mind Over Rhythm), melodious ambient techno and early British deep techno (Bandulu, As One), post-bleep, sub-heavy London club cuts (Epoch 90, Centuras) and hard-to-pigeonhole gems (the bleeping, tribal-infused proto-trance of UVX). It’s a triumphant set all told, albeit one that wasn’t driven by quite as tight a concept as its predecessor.

“It’s just personal favourites – stuff that I bought at the time that I still think are great and interesting now,” Sen enthuses. “One or two, like Orr-Some’s ‘We Can Make It’, were quite big at the time, but you had to be there and experience them. Grooverider and Matthew B played ‘We Can Make It’ a lot but it has been forgotten – it’s a kind of breaks and bass thing. I played it at a festival last year and it went down a storm.”

There is one track on there that offers a direct link to We Ain’t Chicago, though you’d be forgiven if the connection passed you by. It’s Strontium 90’s criminally overlooked ‘Rave on the Congo’, a sub-heavy, extra-percussive workout that comes from a similar sonic headspace to No Smoke’s far more celebrated ‘Koro-Koro’.

“The label it came out on originally was G-Force Records, and I put one of their other tracks – Window Smashers’ ‘Free To Be’ – on This Ain’t Chicago,” he says. “When it came to doing this release, I wanted to represent G-Force again, in part because of the genius of the sadly departed Rob Elliott, who featured on many of their releases and was a DJ on a pirate station in London, but also because it’s a great label that very few people know about. ‘Rave on the Congo’ is properly tribalistic, there’s a bit of a dub influence, and although the track’s use of the melody from the Mission Impossible theme tune is a bit cheesy, the track’s still great. I wanted to sort of connect this compilation to the previous one.”

As for the compilation’s title, borrowed from the name of a Dream Company track showcased on the set, Sen says it was chosen for a couple of specific reasons: “My surname apparently means ‘dream’ in Slavic languages, so when I played in the Czech Republic, all these people came up to me shouting ‘Richard Dream, Richard Dream’! Looking back to the period in the 90s, what was happening back then is all like a dream now. Dance music now is so different – it’s a huge, organised industry with everything neatly arranged into genres and all these little scenes. Back then, it was an idealistic time when everyone loved each other and could play this fabulous, genre-bending music. So Dream The Dream seemed fitting.”

Matt Anniss

Richard Sen presents Dream The Dream: UK Techno, House and Breakbeat 1990-94 will be released by Dance Music From Planet Earth on June 10 – to pre-order your copy on double CD or double vinyl click here