Dusted Down – Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories, a decade on

We re-assess the Punk’s triumphant swansong ten years on

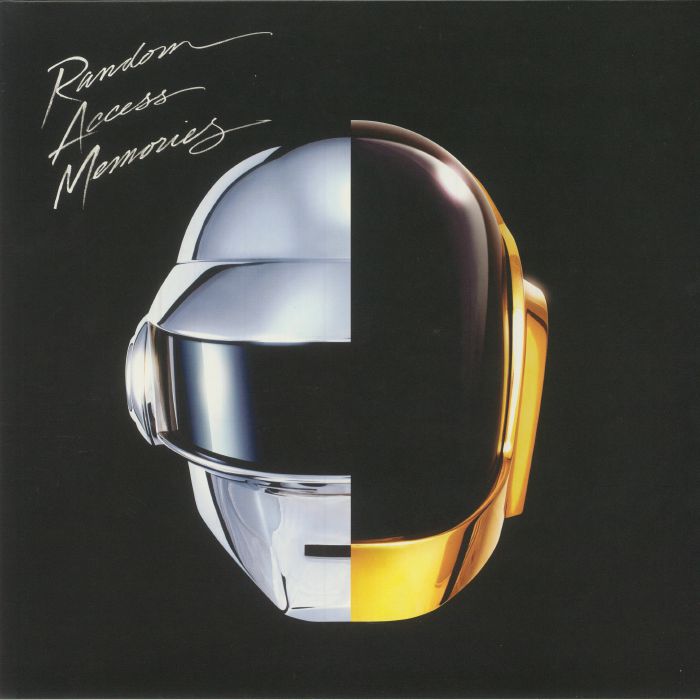

Daft Punk – Random Access Memories 10th Anniversary Edition (Sony)

We’d be willing to bet most music fans are loosely aware of the final, definitive album by Daft Punk. Far fewer are aware why the album resonated just as well for the charts as it did for the chin-stroking audiophile. Why did the retrofuturistic vision of disco, funk and electronica still appeal to a huge global audience in 2013, despite that being arguably one of the least future-facing of all 21st Century years? Why does this album stand out in the popular consciousness as an electronic music classic, when most other albums in that category hail from the 90s? What was Random Access Memories’s it factor?

Many an unthinking music reviewer will call the LP “timeless”. We disagree. In fact, we think its popularity boils down to its timeliness, intentional or not. Don’t believe us? Well, even the name proves us right: Random Access Memories, in computer speak, is a type of computer memory that allows data to be accessed in any order, without the need to access preceding data first. Let’s disentangle this from the technobabble: by naming their album ‘RAM’, Daft Punk were expressing the theme of memory, nostalgia, and the idea of accessing and remixing musical ‘data’ from the past – without inhibition or restrictions.

From the gushing recollections of one Giorgio Moroder on ‘Giorgio By Moroder’ – in which the hi-NRG pioneer recalls his desperate longing to become a musician while living in the Italian town of Ortisei – to the many vocoders and talkboxes on almost every track, as if they were a novelty that had just been discovered now (as opposed to being an inexorable part of the consumer synth boom in the late 70s to early 80s) – there is a feeling of grasping back to some Platonic form of a time. There’s a twist, though. Daft Punk do attempt to achieve timelessness here. With its glossy modern production sheen and intergenerational collaborations (Nile Rodgers to Julian Casablancas), RAM is not a mere mimicry of “analogue” sound or its ghosts. The exclusive treats on the reissue hammer this home: a document of Todd Edwards’ vocal contribution to ‘Fragments Of Time’ (‘The Making Of…’) quite clearly demonstrates Daft Punk’s ability to lay down their music on the fly, ‘in real time’, rather than keeping every aspect of the recording process static, ‘in the box’. The track ‘LYRT (Vocoder Tests)’ – providing a sneak peek at the clicks, pops, capabilities and errors of the vocoders they used – provides another counternarrative, that the components of an album like this don’t just work straight away, and that they take time to perfect.

Deeper dives into the album’s context reveal an attempt to fly the temporal nest. Thomas Bangalter is the son of the late Daniel Vangarde, one of many figureheads who first popularized the genre of disco in 1970s France. Bangalter inherited Vangarde’s crate-digging, sample-based approach to music-making, which made Daft Punk famous. But he recently became the subject of scrutiny for his appropriation of Afro-diasporic songs – Harry Belafonte, and hits by Cerrone and Van McCoy, crop up in several Vangarde productions, forming the backbone of his hedonic disco appeal. But Vangarde failed to give them credit. By contrast, Daft Punk are known to have been meticulous about clearing just about every sample they’ve ever lifted – though the results of this have still been imperfect.

Meanwhile, Giorgio Moroder hails from a prominent family of woodcarvers in his hometown. The Moroders brought fortune to the Dolomite region through woodcraft and trade and are a huge part of its history. Knowing both of these tidbits, it’s easy to see why RAM resonated with the public. Bangalter and Moroder musically express a desire to escape their histories and embrace a rewritable view of the past. The revisionist title ‘Giorgio By Moroder’ is a clue. Narrating himself, he paints his own glitzy history not on a canvas, but on the timeline of a DAW, as a metronome clicks in the background.

Despite making such liberal use of talkboxes, this is an album that rebels against being ‘boxed in’ by the past. Given what Bangalter said around its release – “in electronic music today, there’s an identity crisis, everyone has the same toolkits and templates” – this extends to the present too. But it’s an imperfect attempt. The rejection only relates to the LP’s narrative and making; the obsession with the discoes and funks of the past remains. Plus, recent years have seen Daft Punk implicated into not guaranteeing royalties be sent to sampled artists such as Eddie Johns – arguably unfairly boxing them into the same unjust, pillaging pigeonhole as Vangarde. So, we can only conclude that Daft Punk were quite clever with RAM. They convinced listeners that they had transcended time (in reality, an impossible task) while satisfying the paradoxical urge for familiar sounds. It did the trick.

Jude Iago James

Pre-order youer copy of Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories 10th Anniversary Edition, out May 17, here