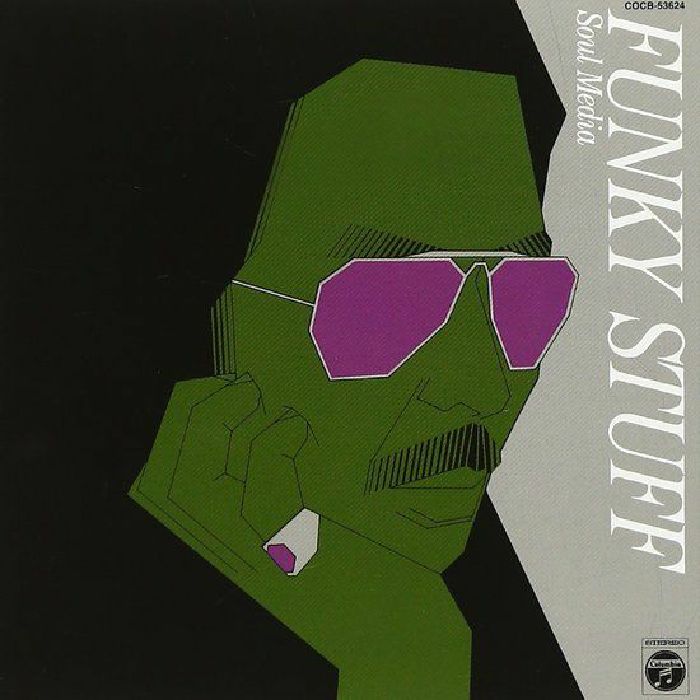

Dusted Down – Jiro Inagaki and Soul Media – Funky Stuff (Nippon Columbia)

Noah Sparkes heads back to 1975 to dust down an undiscovered jazz funk gem

Jiro Inagaki and Soul Media – Funky Stuff (Nippon Columbia)

There is strikingly little written about the creators of 1975’s Funky Stuff. Jiro Inagaki and his band’s legacy remains almost entirely musical, free from the extraneous personal details that cloud many a great jazz player’s coverage. One can only really approach this album by first situating it within the particular cultural context from which it emerges.

From its beginnings, the jazz scene in Japan – estimated to have one of the largest percapita jazz audiences in the world – has encountered countless accusations, from both Western critics and self-conscious Japanese fans, of imitation, unoriginality, and inauthenticity (whatever that might mean). But, in order to assess Inagaki’s work and its degree of innovation, it’s worth establishing a timeline of the fusion experiments from the late 60s and early 70s.

Beginning his “electric period” and broadly considered one of the first fusion recordings, Miles Davis’ In a Silent Way is released in 1969. If critics and jazz purists were unsure of this move, they would be stupefied a year later by the exploratory jazz-rock of Bitches Brew. Aside from these rockier ventures, funk would enter the mainstream jazz idiom with Davis’ On the Corner in 1972 (though it was severely undersold upon its release), Herbie Hancock’s wildly successful Head Hunters and Donald Byrd’s Black Byrd in 1973.

During this period of innovation in the States, across the Pacific, Inagaki was also engaging in this synthesis. The saxophonist’s genre-hopping explorations begin with the terrific jazz-rock of 1970’s Head Rock. Though less experimental than the heady, effects-laden psychedelia of Bitches Brew, Head Rock is significantly punchier, achieving a heavy, explosive energy on cuts like ‘Spoonful’. To compare an album as important as Bitches Brew to a fairly obscure record like Head Rock may seem like a stretch. But given the deep-rooted, harmful stereotypes of Japan as a “nation of imitators”, it is worth pointing out that Japanese artists like Inagaki were not merely inferior copycats – they were often operating in parallel with the frontline of jazz’s many evolutions. Even if these players weren’t mainstream pioneers themselves, their open-minded embrace of the avant-garde and fusion was far ahead of many American audiences.

Though Inagaki himself believed that he wasn’t doing anything new, his quick adoption and subsequent mastery of these new styles is surely worthy of praise. Inagaki would soon abandon the rock influence, opting instead for the funkier inclination of 1973’s In the Groove before fully committing to the genre on the self-explanatory 1975 record, Funky Stuff. Luckily, the album more than lives up to its name, populated as it is by thick bass-lines, wah-wah pedals, and groovy, multilayered percussion. From the first moments of the opener, ‘Painted Paradise’, the record demonstrates its dedication to the danceable spirit of funk. Much like Hancock’s Head Hunters, this often feels like funk with some jazzy improvisation. Notably, all of the tracks bar two are written by pianist and keyboardist for Soul Media, Hiromasa Suzuki.

The laid-back tone of Wayne Henderson’s ‘Scratch’, and a slightly slower cover of Kool & The Gang’s ‘Funky Stuff’ are the only exceptions. The latter is a highlight of the record. Perhaps most well-known from the album is Suzuki’s cooly melancholic composition, ‘Breeze’. The performances, production, and arrangement are excellent, maintaining the groove while bringing a refreshing introspection. This sentiment returns on the touching “One for Jiro” and flows into the swaying bossa-nova of ‘Gentle Wave’. In keeping with the Funky Stuff’s generally uplifting tone, we conclude with the infectious rhythms of “Four Up”.

It’s a fitting, joyous end to the record. One could argue that there is nothing strikingly individual or innovative about Funky Stuff. Indeed, by 1975, jazz-funk had attained a high level of acceptance and popularity – Inagaki wasn’t exactly breaking new ground here. But it doesn’t feel as though it is concerned with pushing boundaries. It is a record on which Inagaki and his collaborators pursue a joyous engagement with the infectious rhythms of funk. It’s a hidden gem.

Noah Sparkes