Varg – Misanthrope

From his Swedish haunt, Jonas Rönnberg speaks with James Manning about the trials and tribulations surrounding his work as Varg.

A nondescript techno record enters the Juno warehouse in 2013. The greyscale artwork and basic red lettering of the label, to the thin black sleeve housing Misantropen, hardly challenged the stereotype of how a mysterious techno record should look. The music, however, combined swathes of ambient dub techno with elongated tones of holographic acid that went far beyond the wonted tropes of replicating Basic Channel and Tin Man.

It was Jonas Rönnberg’s first release; the debut of his prevailing Varg alias, and the piece of music which inaugurated Abdullah Rashim’s now flourishing Northern Electronics label. “I didn’t know what acid techno was when I made that album, I hadn’t heard acid techno,” Rönnberg tells me from Stockholm, cracking open a tall can of Kopparberg cider. After a swig he adds, “I had no idea of how techno was supposed to sound… I come from much more of a metal background, bands, with ‘real instruments’, you know.”

Rönnberg’s candid approach to making electronic music was naturally (unbeknown to him) a liberating factor in the creation of his sound and by extension it offers some explanation to why Misantropen was unique. “This reminds me of Donato Dozzy,” Rönnberg remembers Abdullah Rashim telling him when he first heard it; the Italian’s name completely foreign to Rönnberg at the time. “Now I’m really good friends with Donato,” Rönnberg says, “he makes the best pasta.”

As I discovered, Varg’s entry into electronic music production was the consequence of a violent altercation at a train station in his home town of Skellefteå, Sweden. “I got robbed and they threw me onto the train tracks and I couldn’t move,” Rönnberg says, looking a little uncomfortable. “I couldn’t walk for a couple of months, and I bought a couple of machines and I started to make sounds,” he explains. “This all happened when I couldn’t walk, this whole techno thing…”

Rönnberg is a prolific producer. In two years he’s put out 14 album-length titles alongside a scattering of EPs for labels like Semantica, Clan Destine and his own, now closed Blodörn. Other solo endeavours of Rönnberg – the majority of which have found releases on obscure cassette labels – include Black Leather Harness, Flacid, Grav, Vargrav and Vgra, while outside of his main solo project, Varg, he is one half of Dard Å Ranj Från Det Hebbershålska Samfundet (aka D.Å.R.F.D.H.S) with Michel Isorinne. Furthermore, with Abdullah Rashim he is Ulwhednar, while also forming the Född Död collaboration with girlfriend and fellow Northern Electronics artist SARS.

Rönnberg is a prolific producer. In two years he’s put out 14 album-length titles alongside a scattering of EPs for labels like Semantica, Clan Destine and his own, now closed Blodörn. Other solo endeavours of Rönnberg – the majority of which have found releases on obscure cassette labels – include Black Leather Harness, Flacid, Grav, Vargrav and Vgra, while outside of his main solo project, Varg, he is one half of Dard Å Ranj Från Det Hebbershålska Samfundet (aka D.Å.R.F.D.H.S) with Michel Isorinne. Furthermore, with Abdullah Rashim he is Ulwhednar, while also forming the Född Död collaboration with girlfriend and fellow Northern Electronics artist SARS.

After learning what Rönnberg really meant when he said, “I spent some time on the tracks in front of a subway train,” the inspiration behind the title of his debut opus, which in English translates to misanthrope – a person who dislikes humankind and avoids human society – provides greater context to not only the album, but Varg. “I guess you can tell I’ve lived a pretty rough life when you listen to my music,” Rönnberg says. “I have so many stories of things that went wrong with me in my home town,” he adds, “friends that died at young ages, it’s a rough city for me, I spend a lot of time thinking about my home.”

Even though he imparts, “I’ve never really liked people that much,” Rönnberg doesn’t come across as an unhappy guy, and during our conversation he spills a load of tapes on to a table. “I’ll show you my bag,” he says, rummaging through it. “I have this Walkman in my backpack and with this I have my new tape I put out last week (The Gates of Hermés), and some other tapes I got this weekend.” Shuffling through the cassettes loudly strewn across the table, Rönnberg adds “this is all from last week.”

Within Scandinavian techno lies a furtive DIY tape scene that’s energized by genres like Nordic metal, gothic drone and Svenska-made noise. A great part of Rönnberg’s music drifts sub rosa in this constellation of homespun cassettes, and you’ll find many of his murky productions on minor operations like Periferin, Kollaps Records and the Malmö-based Funeral Fog, to others like Beläten, Total Black, Brutal Discipline and Posh Isolation.

In 2014 Rönnberg set up his own label Blodörn which was only active for that year, and it provided a platform for associated artists and friends (and Varg aliases) to release music. “You can be really spontaneous (with tapes) and I like that,” Rönnberg says. “When I played three shows in Tokyo in one week I put out a tape that was only available for that tour, and that was recordings from the rehearsals,” Rönnberg explains.

“Vinyl is like a flash photo of a person, it will show everything,” Rönnberg says of a record’s sonic qualities, “with tapes,” he adds, “it’s like a photo without the flash.” Cassettes have long been a loved medium for the experimental, noisier end of electronic music, in part because of the way tape colours sound, but another attraction, moreover, is the ease in which cassettes can be cheaply manufactured. “I can duplicate four at a time, at 16 times the original speed,” Rönnberg says of his own capabilities, and to make a point he adds, “I could make a tape after our discussion.”

Rönnberg’s association with cassettes isn’t exclusive to the obscure and isolated. He’s formed a strong connection with Stephen Bishop’s blossomed Opal Tapes, and the label have released two albums by D.Å.R.F.D.H.S, while other full lengths by the project have made their way to vinyl through Field Records and Clan Destine. “Opal Tapes get our more beat-y stuff,” Rönnberg says, “we have some things that we know as soon as we’ve recorded it, we’ll send it to Stephen.”

Each week Rönnberg and Isorinne meet to work on D.Å.R.F.D.H.S. It’s Wednesday night when we speak, Rönnberg has just come home from hanging out with Abdullah Rashim and I ask how his session with Isorinne went. “It was good except we were really tired,” he answers. “Usually when we meet we record five tracks, at least, and yesterday we only did two.” With a solid amount of D.Å.R.F.D.H.S. material now out there, Rönnberg reflects, “in the beginning it was quite hard because we did retakes on every track to get everything perfect, but now we know how to set everything so it’s good from the start.” Rönnberg adds, “we record to one stereo track, erase everything and just go on… the new double LP on Field Records, that’s two days’s work in the studio.”

Isorinne is ten years senior of his partner in D.Å.R.F.D.H.S. and when it comes to the production dynamic, “Michel likes to play the keys, he really likes to come up with key stuff,” Rönnberg says. “He’s really good at twisting those really sad melodies of the project, while I’ll make more of the drums, the noisier parts.”

“We’ve never talked deep about our music ever,” Rönnberg adds, “we live separate lives; we meet, we record, and we record a shitload of music.” From what Rönnberg tells me, his relationship with Abdullah Rashim is much closer. “We hang out everyday,” Rönnberg starts. “He’s one of my closest friends, we meet for dinner or lunch, and we spend a lot of time talking about the progression of what we’re are doing.”

As Ulwhendar, Varg and Abdullah Rashim create a brutally brittle form of techno, and the project’s debut record was the result of an illegal party they played in Stockholm. Before the gig, Rönnberg remembers pitching the idea of a tribal drum set to Abdullah Rashim; “hey, couldn’t we bring my 808 and your 808 and do this really fucked up live set where we super distort mine and yours is clean?”

“So we rehearsed this for one day in the studio and recorded everything, and then we did the show and didn’t really talk much more about it,” Rönnberg remembers. Some time afterwards Rashim sent Rönnberg a bundle of tracks with the message, “you probably want to listen to this,” which subsequently became Ulwhednar’s debut album, LP. “The whole album is about the Stockholm Bloodbath,” Rönnberg explains, a topic that had me scouring Wikipedia for references, like “Stortorget”, which is named after Gamla Stan, a public square in Stockholm where the historic atrocity took place.

After moving to Stockholm “the day he turned 18,” Swedish bloodbath territory is where Rönnberg says you’ll usually find him, “drinking a coffee around central station like any other tourist”, not, “in the record shops.” After a 12-hour migration from Skellefteå, he remembers arriving in the capital during the early hours of the morning, and from my discussion with Rönnberg I can’t help but sense he relishes the feeling of being somewhere new, a tourist, even if it is in the city he’s resided for the past six years.

After moving to Stockholm “the day he turned 18,” Swedish bloodbath territory is where Rönnberg says you’ll usually find him, “drinking a coffee around central station like any other tourist”, not, “in the record shops.” After a 12-hour migration from Skellefteå, he remembers arriving in the capital during the early hours of the morning, and from my discussion with Rönnberg I can’t help but sense he relishes the feeling of being somewhere new, a tourist, even if it is in the city he’s resided for the past six years.

Rönnberg’s second album as Varg, Ursviken, was released at the end of April and he calls it a “second step” from his first. “Misantropen is about the mystery of the city where I am from and this will probably be the last record about my home town and where I grew up,” he says of Ursviken. “It won’t sound like Misantropen at all, but I still think you will get the right Varg vibes,” he adds.

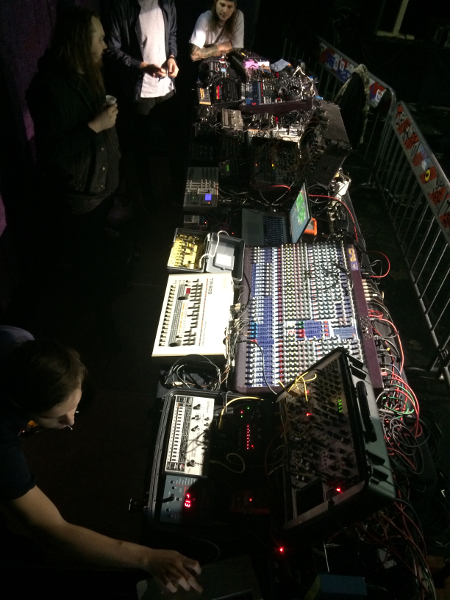

“Half of the album is recorded at Abdullah Rashim headquarters with his machines because I felt like I needed supervision doing this,” Rönnberg continues. “I have a really clear focus on what I want to do as Varg… I really need to focus, so I left my studio which is a mess,” he says. “I don’t have a studio, I just have all my synths in boxes, or laying around… I have synths on my floor, everywhere, like sat against the walls.”

Misantropen was the result of a forming friendship with Abdullah Rashim who “had this idea for a label,” Rönnberg remembers. “He asked me one night while he was out playing if I wanted to release any music,” and Rönnberg divulges, “I was like yeah, yeah for sure, and he gave me a deadline… I was way over the deadline and he asked me again at some other club night, OK, this is the new deadline and we’ll do it like this; you’ll come to the studio at this date and you will present some stuff that I will release.”

“So in some sense he really trusted me,” Rönnberg feels, “I went home and recorded my first ever track, “Stambanan”, which is on Misantropen.” After sending his first efforts to Rashim it was met with the response, ‘hey, you’ve made an album’, and as Rönnberg remembers, “I was like, ‘oh fuck, is this even good music?’” Abdullah Rashim’s reply: “yeah, trust me, I’ll put it out, this is good.”

Donato Dozzy and Neel were the first to book Varg for a show outside of Sweden, and Rönnberg remembers not fully comprehending the significance of that booking, however doing his best to take in the gravity of the request. “Abdullah was like ‘this is really huge’,” Rönnberg recounts. “They had just opened up their new night Strati at Brancaleone, an old club in Rome where Donato used to be a resident,” Rönnberg explains. “This was the first night they ever had, Neel and Donato together, and this was the first night in a long time that they had done anything at Brancaleone,” he says. “I went down and I understood it was a huge deal for them.”

Rönnberg’s work, like a lot of industrial, experimental techno, can easily be painted as dark; a poor descriptor given to music that, to put it basically, isn’t light. “I don’t get so moved by happy things so when I am in the studio the music can be really full of anxiety – when you listen back to the music – but I think that’s how I get touched by it,” Rönnberg says. Taking into account the title of his first album, and that harrowing incident which ultimately led to its inception, Rönnberg’s life could have taken a turn for the worse. Instead it exhumed a hidden talent from within the Swede who once harboured feelings of resentment and disdain to his fellow person, to now saying, “I have people around me that I really like.”

Interview by James Manning

All images courtesy of Jonas Rönnberg