Turning The Past: An Interview With Ricardo Tobar

Ahead of a debut album that’s been a long time coming, Chilean producer Ricardo Tobar discusses his roving lifestyle, production methods and more with Josh Hall.

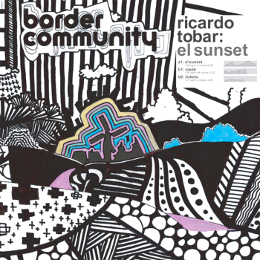

Since at least 2009, Ricardo Tobar has been giving interviews suggesting that he’s been working on a full-length, and Treillis, his debut LP, comes half a decade since his first release for Border Community. In these interim years Tobar has been responsible for a series of EPs on labels such as German stalwart Traum Schallplatten and the rising In Paradisum, building on the technicolour pastoral of his earliest work with gradually more concessions to the dancefloor. These releases have, however, been sporadic; between 2007 and 2012 he released an average of just over one short-form record a year. So why the radio silence, Ricardo?

“I was searching for a sound that wasn’t really the best,” Tobar says via Skype from his Paris home. “I wasn’t really sure of it. I was trying to make something different, but I wasn’t feeling it. So years go by, and I was playing a lot of gigs, and I was travelling a lot, and moving from country to country. I wasn’t doing so much music.”

On Treillis Tobar continues to misshape house and techno, favouring gleefully vitiated synths and lurching, crazy paving kicks. The bouncing ball playfulness of breakout “Boy Love Girl Song”, though, has been jettisoned, or at least toned down, and in its place the producer has found a new, impressionistic mode that is simultaneously rough hewn and refined; a sound that is redolent with dusky melancholy but never feels self-absorbed. This is introspective music, but it seems to be informed by universal experiences; vague, nameless sadness, and a pensive despondency that lurks even in times of happiness.

That disconsolate main joist can be heard even at his most floor-facing work, as on, for example, last year’s “Together”, or the comparatively demonstrative album track “Hundreds”. “A lot of people tell me that,” he says, “even my friends. I don’t try anything, really. I just make songs that I feel good with. Mostly they are a bit melancholic, but I don’t know why. But usually when I listen to music, it’s that melancholic melody. I’m always looking for the past, maybe. I try to live in the present, but then I always move to the past. Maybe it’s that.” Is there a sense, then, that the past is more appealing? “The future you never know. The present is so difficult. So the past you can turn. You can think of the past, and something bad, and you can make it good – you can change it in your mind.”

That disconsolate main joist can be heard even at his most floor-facing work, as on, for example, last year’s “Together”, or the comparatively demonstrative album track “Hundreds”. “A lot of people tell me that,” he says, “even my friends. I don’t try anything, really. I just make songs that I feel good with. Mostly they are a bit melancholic, but I don’t know why. But usually when I listen to music, it’s that melancholic melody. I’m always looking for the past, maybe. I try to live in the present, but then I always move to the past. Maybe it’s that.” Is there a sense, then, that the past is more appealing? “The future you never know. The present is so difficult. So the past you can turn. You can think of the past, and something bad, and you can make it good – you can change it in your mind.”

For Tobar, the present seems like a challenge. His life has been peripatetic of late, having first moved from his native Chile to Berlin, and now to the French capital. Berlin, he says, was more important for his personal life than for his music. He moved there “just after the earthquake in Chile”, the 2010 disaster that devastated the country, claiming more than 500 lives and destroying the homes of one in ten people living in the areas affected. “That was really traumatic,” Tobar says, “then I moved to Berlin. It made me tougher. ”Paris, meanwhile, is stressy. It’s been difficult. I come from a city (where) you can see the ocean all the time, and nothing can stress you. Since I’ve started travelling it was difficult to know this reality. You are so far away. In Chile everything takes time. If you want even to travel to Argentina it’s long, you know. So coming to Europe, and then living here because you are trying to make music and you are playing gigs – it was a bit hard. So I suppose that’s also why I didn’t release an album before: trying to connect with this new world that I was living in.”

“There are a lot of artists that are doing awesome stuff and they die in the underground. Nobody cares.”

Constant travelling has also led Tobar to pare down his production setup to the point where it consists of “only the stuff I use for playing live. It became my studio.” During this period of upheaval Tobar states he became “annoyed by the idea that I couldn’t separate the live thing from making songs. When I was in Chile I had my room and it was like a studio, and I never played live. I had all my things there; it was really easy for me to sit and do a song, because I didn’t have any pressure. I didn’t have any normal stuff,” adding that he “was playing live, and using the same computer to plug everything (into) in the studio. The other weekend I had to play (a gig) so I had to disconnect everything. I hate it.”

Playing live has transformed the sound of his records however. Having initially been frustrated by his inability to delineate between a live sound and a recorded version, Tobar has now felt the influence of live performance seep into his writing process. “I’ve learned a lot from playing live,” he says. “You know what works and what doesn’t work. Usually my song doesn’t work, so I have to make it work in a live

context. I have to put the kick louder. You have to search for the right mix. It’s really weird, because when you are making songs, you don’t think about that. But when you are playing live you are like, ‘Oh, well this sounds bad.’ People notice that. On an unconscious level they know that the song doesn’t work.”

This new, more acute awareness of the dancefloor can be seen most clearly on lead single “If I Love You”. This is straight-up house played through Tobar’s woozy, tape-warped filter: a rough-hewn approximation of club music, but one that still has its centre of gravity in the Norfolk-wave esoterica of his early material. “If I Love You” was, Tobar says, the first track written for the album. “I had this song, and I did everything surrounding it. I think it’s the main song on the album.” Rather than starting out with an overarching aesthetic for the album, Tobar adds that the rest of the tracks were born from “If I Love You”. “I thought the song was meaningful,” Tobar believes, continuing, “I like the melodies, and the melodies tell me something. I can feel connected to the song. That’s important, and I wanted to do the album so that when you hear the album you feel connected. It can push your mind to think, to start to realise that you are alive.”

This new, more acute awareness of the dancefloor can be seen most clearly on lead single “If I Love You”. This is straight-up house played through Tobar’s woozy, tape-warped filter: a rough-hewn approximation of club music, but one that still has its centre of gravity in the Norfolk-wave esoterica of his early material. “If I Love You” was, Tobar says, the first track written for the album. “I had this song, and I did everything surrounding it. I think it’s the main song on the album.” Rather than starting out with an overarching aesthetic for the album, Tobar adds that the rest of the tracks were born from “If I Love You”. “I thought the song was meaningful,” Tobar believes, continuing, “I like the melodies, and the melodies tell me something. I can feel connected to the song. That’s important, and I wanted to do the album so that when you hear the album you feel connected. It can push your mind to think, to start to realise that you are alive.”

“If I Love You” has also been the subject of a remix package, with new versions contributed by a clutch of unexpected artists exploring the hinterlands of house and techno. Samuel Kerridge’s rework submerges the melody in dusky reverb, pinning it behind globular kicks. D’Marc Cantu pitches nauseating side chains against enchanted vocals and dissonant synths. “When Desire sent me the remixes I was like, ‘yes, proper dance music,’” Tobar says. “I have a lot of people that still connect me to Border Community and that’s amazing. But I thought if I do an album, I want to put in the mind of these people, other kinds of music. Just things that I’m listening to, and (music) I found really good and that I think the people that follow me need to listen to.“

Tobar has always worked with basic studio equipment, but the true depth of his no-frills approach remains startling. Lacking monitors, he has mixed all of his releases to date on what Tobar describes as a crappy radio. “Everything got released like that, so I suppose that’s why DJs (don’t) play it. It doesn’t work, because the mix is really shitty,” he says. Although Tobar has now invested in some “proper analogue” equipment, he remains wedded to a lo-fi aesthetic, no longer through necessity, but because of his admiration for the noisier end of the indie guitar-music spectrum.

“When I started to make electronic music,” he says, “I wasn’t listening to electronic music. I was listening to indie stuff; rock records. And then I listened to Border Community, and then everything felt OK – it’s not really wrong what I’m doing – so that’s why I sent everything to James (Holden). But I think everything was really lo-fi and I was trying to be like them. You always have music that you like and you try to be better. I think there’s competition. When I was more connected to James we were sending tracks and it was always like, ‘this is awesome – I will try to do it better,’” he adds. “I think music works a bit like that for me. I try to make things better. So when I was doing the lo-fi stuff, I was trying to do it lo-fi – but better.”

“When I started to make electronic music,” he says, “I wasn’t listening to electronic music. I was listening to indie stuff; rock records. And then I listened to Border Community, and then everything felt OK – it’s not really wrong what I’m doing – so that’s why I sent everything to James (Holden). But I think everything was really lo-fi and I was trying to be like them. You always have music that you like and you try to be better. I think there’s competition. When I was more connected to James we were sending tracks and it was always like, ‘this is awesome – I will try to do it better,’” he adds. “I think music works a bit like that for me. I try to make things better. So when I was doing the lo-fi stuff, I was trying to do it lo-fi – but better.”

Stating his love for noise, Sonic Youth particularly, Tobar explains, “when I listen to their albums it’s just…how can they do that, you know? They have a really nice melody, but they put all this noise around the melodies. Music like that just blows me away. I’m trying to do that but at the electronic level. All the time I’m searching for the right noise, even just a little click in the song.”

When Tobar began releasing on Border Community the label’s signature sound remained out of step with the dance music majority. Briefly, though, that sound came to dominate and its influence can still be heard in the work of artists like Gold Panda. “You have really good music now,” Tobar enthuses. “When I was doing electronic music in my room in Chile, I was only listening to really old Warp stuff, but in the mainstream you had nothing, not for me. None of this is mainstream in Chile; people don’t even know what Border Community is. But when I was looking to the people that were playing in Chile, and I was looking at the music they made, it was crap – this minimal stuff, or this progressive trance. I thought, ‘if this is electronic music, I don’t know what I’m doing.’ But now you have a lot of people like Actress, and they are amazing. My music doesn’t sound like that, (but) I found that Actress, and all this indie or deep techno stuff people are making, is amazing.”

Tobar’s post-Border Community journey has now taken him to French imprint Desire. “They are really punk,” he says. “I’m really into that, to do it yourself. You can do whatever. You can do the music, and they will say yes or no. There are some labels that don’t say anything. They keep quiet, and you never know if the music is bad or not. You need honesty. I would like more people like that.” Tobar would like to tour, but suggests that the sheer volume of records being released makes this difficult for an independent artist. “There is so much music now. It’s really difficult; it’s like we are all drowning and we are trying to survive. It’s tiring. When I started with the EPs I was just releasing (them) because it was great. I wasn’t really paying attention to what was happening. And then all of a sudden it was like 2011, and I thought, ‘this is weird, you can release now and nobody will notice. No one will care.’ And even if the music is amazing, there (are) a lot of artists that are doing awesome stuff and they die in the underground. Nobody cares. Before it wasn’t like that, you could make a good record and people would notice.”

Dying in the underground, though, is not an idea which Tobar is necessarily enthused. Although he says he is not overly concerned about recognition, he clearly remains angry about other, more commercially successful artists appropriating the Border Community sound. “When I put the first records out, I thought there (were) a lot of people copying this. Everyone in Border Community thought that way. Sometimes it’s really obvious, and sometimes it’s not, but you can feel it. So you see these awful people going really famous, and you think, ‘but this guy is copying me. He’s doing the same stuff. He’s doing the same melodies.’ It’s so obvious that you start to think, ‘why is this happening?’ The mind is really weird. I’m not egocentric – or maybe I am – but when you feel that people are stealing (from) you, it’s a weird feeling. When you start feeling that people are getting recognition with some songs that sound just like your song, you think, ‘well, why am I not in that position?’”

Dying in the underground, though, is not an idea which Tobar is necessarily enthused. Although he says he is not overly concerned about recognition, he clearly remains angry about other, more commercially successful artists appropriating the Border Community sound. “When I put the first records out, I thought there (were) a lot of people copying this. Everyone in Border Community thought that way. Sometimes it’s really obvious, and sometimes it’s not, but you can feel it. So you see these awful people going really famous, and you think, ‘but this guy is copying me. He’s doing the same stuff. He’s doing the same melodies.’ It’s so obvious that you start to think, ‘why is this happening?’ The mind is really weird. I’m not egocentric – or maybe I am – but when you feel that people are stealing (from) you, it’s a weird feeling. When you start feeling that people are getting recognition with some songs that sound just like your song, you think, ‘well, why am I not in that position?’”

Following the completion of Treillis, Tobar is now concertedly trying to turn his back on the sound that defined the earlier part of his career. As is the case, he says, with Holden, Nathan Fake and Luke Abbott, the Chilean is experiencing a shift, the mid-point of which is represented by Treillis. The record straddles two worlds; the sound of Tobar past and the comparatively souped-up aesthetic of Tobar’s future. “I wanted to do something really different,” he says, “but now when I listen to the record (Treillis), and I listen to the past EPs, I think it’s not so different. I don’t like copies, and I don’t like copying myself, (but) I guess we are trapped because we are not different people. We are trying to make everything different, but in a way when you press ‘play’ you see, oh, this guy is Ricardo.”

Interview by Josh Hall

Treillis is released next week on Desire Records