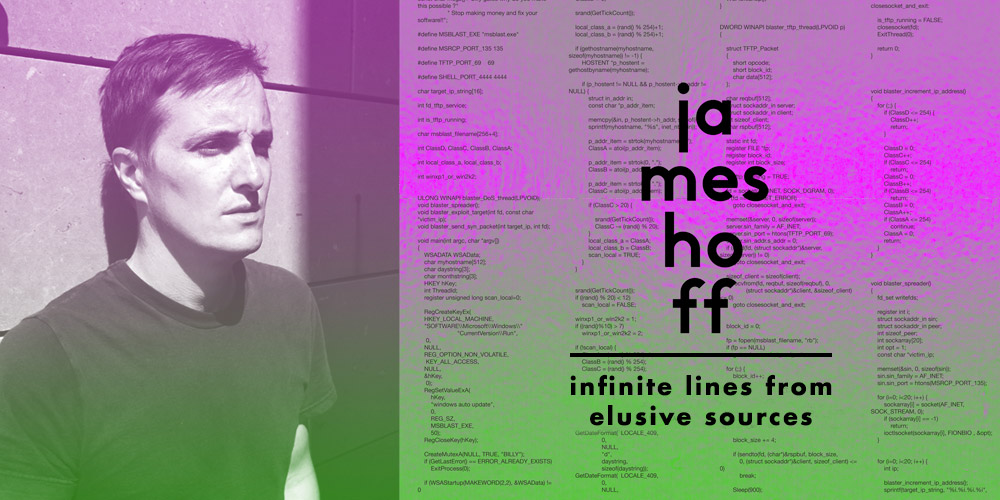

James Hoff – Infinite Lines from Elusive Sources

The New York based conceptual artist discusses his various stylistic practices, his role in non-profit organisation Primary Information, the future impact of new streaming platforms and more with Ian Maleney.

Working out of his studio in Brooklyn, James Hoff has long pushed against the boundaries separating the worlds of experimental music and contemporary art. His artistic practice ranges from painting to conceptual installation work, from layered field recordings of historic riots to the virus-infected 808 beats of his latest LP, Blaster. As well as being a practicing artist, Hoff is also the co-founder and editor of Primary Information, a non-profit art publisher and, increasingly, an experimental record label.

Released last year on PAN, Blaster is Hoff’s most accessible work to date and a prime example of the working methodology he’s been developing over the past few years. The first side of Blaster contains seven short tracks made largely with samples of a Roland TR-808 drum machine which have been corrupted with the infamous Blaster computer virus, which infected half a million Microsoft computers in 2003. The infected samples are sometimes recognisable, but more often they become distorted, disintegrating into noise. Hoff arranges these samples into a set of rhythmic tracks. They’re not exactly pulsating techno, but physically invigorating all the same. The second side of the record has just one track, containing the individual samples Hoff used to make the first side – an invitation for others to have a go with their own corrupted sample pack.

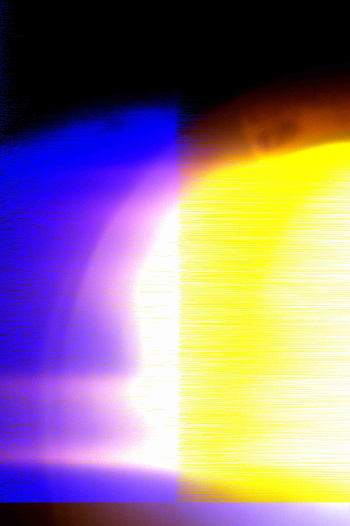

Hoff has also used various viruses, like Stuxnet and Skywiper, to infect his visual works, like paintings (see an example below). While the strange colour formations of these paintings are incredibly beautiful, it feels like music is a more natural host for these kinds of experiments. As Hoff points out, music has a tendency to travel in unexpected ways, replicating itself as it goes.

“I think music is really special in the way that it can travel very quickly beyond the context through which you release it or put it out,” he says. “Music has a way of self-distributing or travelling through channels that you wouldn’t normally think that it would get to.” As an example, he points out a car driving down his street, “they could be playing a song very loudly out of the car and that song could be stuck in my head for a long time today, or tomorrow, or whenever. It could come back to me. I really like that about music.” Hoff feels visual arts don’t share this luxury, “I think with music, it’s very special the way that it attaches itself to certain contexts, certain situations, certain forms, certain places.”

“I think music is really special in the way that it can travel very quickly beyond the context through which you release it or put it out,” he says. “Music has a way of self-distributing or travelling through channels that you wouldn’t normally think that it would get to.” As an example, he points out a car driving down his street, “they could be playing a song very loudly out of the car and that song could be stuck in my head for a long time today, or tomorrow, or whenever. It could come back to me. I really like that about music.” Hoff feels visual arts don’t share this luxury, “I think with music, it’s very special the way that it attaches itself to certain contexts, certain situations, certain forms, certain places.”

Though it is obviously has a conceptual core, Blaster is more than an experiment in auto-generative music. It stands on its own, apart from its elaborate conceptual framework. Rather than relying on the system to define the work, it’s the personal, unique arrangement of raw material that makes the album what it is.

“There is a temptation to want to disavow the aesthetic sensibility of work and totally not deal with it, but I’ve always fought that urge in myself,” says Hoff. “It’s important for myself personally that I have the last word as a person, not the rule-based system.” Hoff acknowledges the Blaster virus worked really well because it helped him do a few different things, primarily create a palate from which he could further create. “I had a lot of freedom in terms of how I was able to assemble and compose after that generative process, both in painting and with music. It allowed me to really tie together a couple of different practices of mine into one working method.” Using these viruses, Hoff tells me, “I’m able to work across a multitude of platforms and media in a way that I wasn’t able to before. Which was really great for me, because it allowed me to more concisely focus on a larger practice as opposed to a singular one.”

This larger practice is also one intimately tied to the political sphere. Though the work is abstract, never coalescing in either audio or visual terms into familiar patterns or images, it maintains an oblique commentary on the more concrete world of technology, the state and the military. Sitting just below the surface of the work, these political connotations offer a near-bottomless pool for speculation and interpretation.

“Using things like StuxNet and SkyWiper were an effort to connect the singular process of art-making to a larger phenomenon and a political one as well,” says Hoff. “I totally think that it’s a responsibility of artists, or has become one at least in the last fifty years, to try to make sense of military technology and to try to use it create events. So I think it’s not something you can do with everything, but I’m constantly thinking about those issues as well. I was sort of misquoted last fall, for whatever reason, about the virus paintings, the Skywiper and StuxNet paintings, not being political, which they definitely are. They’re using State-sponsored computer viruses so it would be hard for them to stand outside of a political framework, even if you can’t necessarily read an ideology inscribed in the surface.”

Implied in all this work is an interest in the way music, and information more generally, travels online. There has obviously never been a better time to be searching for information, with huge libraries of previously unavailable music and art now accessible with just a few clicks. Though there are well-documented pitfalls to the commercial model in the networked age, artists too are in a position to disseminate their work more widely than ever before. Chances are, even if an artist isn’t too pushed about such things, someone will do the job on their behalf.

“In the sixties, when artists were taking out advertisements in national magazines to insert a project, that meant something totally different then than it would mean now,” says Hoff. “Artists have a greater ability to control the language and the conversation around their work and I think that’s definitely a good thing, but I’m sort of interested in what happens when the artist loses that control and the work sort of escapes out.” For Hoff, in terms of setting up a system for production, “it’s just as important to set up a system in which the work is allowed to do that. In terms of creating a work that can function as a song that can travel well beyond the official modes of distribution that it’s been placed in.”

Though there are differences in the way a pop song travels compared to a piece of avant-garde experimental composition, the internet has opened up and made available a large selection of work that was previously near-impossible to find. Databases like Ubuweb and Aaaaarg, as well as more secretive peer-to-peer file-sharing networks, host thousands of works by the 20th century’s most adventurous and progressive artists, many of which could never have been accessed by the average person even ten or fifteen years ago. One of Hoff’s earlier projects, the Endless Nameless collaboration with another New York artist, Danny Snelson, attempted to investigate the information and work contained within these networks and databases, and to examine the way it was constructed and shared. Running from 2008 to 2010, the pair began collecting, exhibiting and eventually selling all the avant-garde culture they had collected, at rock-bottom prices of course.

“We infiltrated all these avant-garde file-sharing networks and collected three or four terabytes of material,” says Hoff. “We were really interested in the hierarchies of information that existed within these avant-garde cultures or what came to be defined as experimental or avant-garde. We took all this material and then we started curating work onto hard-drives which would be like little exhibitions inside exhibitions, here and in Europe.”

“How much experimental, avant-garde culture is going to migrate to these larger digital platforms like Spotify or Tidal or Apple Music, or any of these other things?”

Hoff tells me he was compelled to take a step back and see what got lost in the process of digitising information. “The publisher was almost always lost. In terms of how we order information online, if you go to Ubuweb, you’re not going to be able to choose something by publisher on there. It’s just not there. You’re going to be able to choose by artist or medium, so that was interesting.” Delving further into these structures to see who was really controlling these platforms also proved interesting for Hoff. “It’s probably of no surprise that it was white men and it was very few of them. It wasn’t a very big community in the end. We infiltrated them pretty successfully by posing as women in these forums and it was very easy to climb the ranks.”

The internet and its modes of distribution have changed a lot since 2010. For one thing, it’s a lot less wild. Many of the fuzzy borders around file-sharing have been shored up and re-enforced. The loose network of blogs like Mutant Sounds that shared old, weird music on Mediafire and Megaupload toward the end of the last decade are mostly all gone. Many forums have gone quiet. Torrents, for anything other than TV shows, are harder to find than ever. There has been something of a consolidation, with the biggest names in the tech world moving into previously uncharted territory, while new names like Spotify have appeared and staked a claim.

“It’s interesting to see how that culture changed so quickly, in terms of the blogs and forums that I used to to get torrents and things like this are just completely gone at this point,” says Hoff. “How much experimental, avant-garde culture is going to migrate to these larger digital platforms like Spotify or Tidal or Apple Music, or any of these other things?”

Hoff goes on to discuss his curiosity at how streaming will play out with the more underground communities. “I tend to think these artists and communities are pretty resilient and always find a way to make things their own and to carve out their own niche within these platforms and frameworks. I’m interested in seeing how we take control of the technology, which I think we will do eventually.” He feels there will be a time when the space that was originally occupied by micro-distros will be occupied by a “micro-Spotify” in some capacity. “So instead of Fusetron the distro, you have Fusetron the app. And I would be psyched to have that app for sure, and I would be psyched to be on it.”

As a musician Hoff’s medium has been greatly affected by the digital era, but as a publisher of experimental art books, he says the disruption has been “almost nil”. While albums are easily shared online, Hoff feels that a well-published art book is impossible to replicate. Their beautiful physicality has seen the market for art books grow substantially over the past decade or two. Before founding Primary Information, Hoff worked at New York press Printed Matter, which started the Art Book Fair in 2005. What began as a niche attraction is now a three-day event that draws over 25,000 people. Primary Information has been similarly involved in the field, helping to draw attention to the foundational work done in this area by artists like Lee Lozano, Aram Saroyan and Max Neuhaus.

“I think that as we grow more reliant on reading things on a screen, the flip-side of that is that people are more interested in having books again because of the tactile nature of reading them, holding them, and feeling them,” says Hoff. “An artist’s book and this sort of structural reading of an artist’s book, how the work relates to each turn of the page or the smell, whatever the artist puts into the book itself, is very tough to accomplish on an e-reader, which I think are more geared toward trade fiction.”

“I think that as we grow more reliant on reading things on a screen, the flip-side of that is that people are more interested in having books again because of the tactile nature of reading them, holding them, and feeling them,” says Hoff. “An artist’s book and this sort of structural reading of an artist’s book, how the work relates to each turn of the page or the smell, whatever the artist puts into the book itself, is very tough to accomplish on an e-reader, which I think are more geared toward trade fiction.”

Hoff reels off a quote from someone he doesn’t remember to reinforce this point. “I don’t know who said this, but it was something like, ‘I can only tell what book I’m reading by the way it smells’, and I think that’s very telling. That’s something you clearly lose with a digital book. I mean, the person who said that was talking about fiction, but that one thing is what an artist’s book is capable of bringing to the table that is not capable of being transferred to a digital platform.”

That said, Primary Information has begun to publish a significant amount of work online, re-publishing catalogues and art books from the 1960s and ’70s in PDF form, often for free. While it’s not exactly competition for their main focus of selling physical books and records, it does open up the work to a whole new audience.

“For us, it’s a decision; should this be a PDF, should this be online, should this be free, or should this be a physical book? The answers to that question are different for every project, and not necessarily ideological,” says Hoff.

“It poses an interesting question for the organisation because one of our main missions is to provide access to historical material which is no longer available to the general public outside of a collection or a collector.” He refers to the Seth Siegelaub archive made available by Primary Information. “They were downloaded, within a week, over a hundred thousand times. Together – there were six books. One of them, the Xerox book, which is the most famous one, was downloaded sixty thousand times in a week. Which is pretty insane to think about in terms of this really, really niche artist’s book. It’s an infamous one, but it’s not a famous one, not really.”

Hoff admits he finds that kind of demand mid-boggling, “but it creates a situation where we think, well maybe we should just be publishing everything online, if it provides that kind of access.”

As musician, artist and publisher, Hoff is clearly fascinated by the ways in which work can filter out into the world. Making the work and then surrendering it to the world, this is Hoff’s approach. All that’s left for him to do is find the best host – music, painting, books, whatever – for his parasitic ideas to flourish within. His work is designed to spread, to find itself in situations its maker could barely have imagined, continually seducing and surprising the people it eventually reaches.

“Once you pass a certain threshold, in whatever way, whether it’s through genre or through sales or some other form of measurement, you certainly have a lot less control,” he says. “I think that that’s kind of exciting in a way. I’ve always thought of the music we listen to in waiting rooms as a really ideal place to land. I doubt seriously that Blaster will ever land in that venue but I like the idea of the music that narrates non-space, the music that narrates our lives as we’re busy travelling from place to place, and within an architectural framework that is ambiguous. That would be the ideal venue for a lot of work. If I could figure out how to land there, I would be very happy.”

Interview by Ian Maleney

PAN on Juno

All images by Roman März courtesy of the Supportico Lopez gallery, Berlin

James Hoff European Tour Dates:

Sep 17 – Ultima Festival, Oslo*

Sep 29 -Budapest, UH Fest

Oct 4 – Vienna, Rhiz**

Oct 7 – Berlin, TBA**

Oct 8 – Brussels, les ateliers claus

Oct 9 – Antwerp, stadslimiet**

Oct 10 – Paris, Treize**

Oct 14 – London, TBA

*w/ Afrikan Sciences

**w/ C Spencer Yeh