The Art of Failure: Lnrdcroy

In light of a wonderful debut album for 1080p, Vancouver-based artist Lnrdcroy speaks with Brendan Arnott about his sprawling influences, ambitious approach to performing live and life in British Columbia.

In Stephen Lavelle’s video game Slave of God, you navigate through a nightclub while on hallucinogenics. The results are what you might expect: kaleidoscopic colours dance over the screen, pulsing hearts and glowing religious symbols appear over the blocky polygon-shaped bodies of the other clubgoers you interact with, and at one point a sports car crashes through the ceiling, narrowly missing the dancefloor.

Get past the surreality of the experience, and what keeps you coming back to Slave of God is its dedication to immersing you in a place and a feeling; not only are you in a club, you’re scanning the blurred cornucopia of flashing lights passing before your eyes, trying to decipher some kind of meaning. For many of us who grew up in small towns outside of city centres, in a pre-internet age, those nightclubs and warehouses were experiences that pieced together the few rave signifiers we saw reflected in popular culture. We painted a picture of places we didn’t have access to, because there was no other option.

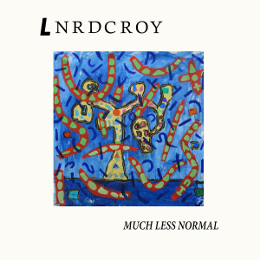

Vancouver-born-and-raised producer Lnrdcroy (pronounced “Leonard Croy”, real name Leonard Campbell) has manifested his own vision of shadow-consumed warehouse spaces lurking at the edge of town; his stunning debut album on tape-based label 1080p embodied the rave signifiers that Campbell grew up around. Trace fragments of Orbital, Aphex Twin and Underworld are present, alongside dusty house signifiers and rolling Balearic ambience, but these sounds are recontextualized to suit the dense forests and perpetually rainy shores of Canada’s West Coast. Campbell’s waterlogged techno and cosmic electronica is about recreating that environment of escapism, hedonism and euphoria that he dreamt of as a youth – music that’s about the club as much as it is for it.

Typing over Skype while he sips from a pot of coffee, Campbell has asked for a text-based interview – but, instead of a desire for anonymity, it’s because his voice is “shot to hell” as he goes through the dually un-fun process of overcoming a cold and dealing with a quitting-smoking raspy cough. It’s a small disruption from his daily schedule- “overall, the structure of my routine hasn’t changed in eight years” he tells me, listing his morning rituals: “wake up, shower, coffee, and go into the studio. I have a lot more bookings this summer and I’m – perhaps ambitiously so – trying to create new material for each show”. It’s because of this Campbell “can’t let little things like a cold stop me from working.”

Now 25, Campbell’s production work has extended over half his life, where he’s utilized DIY-programming tools and frequented forums for the last 13 years. Despite the longevity, his first experience of dance music is still clear in his head. “When I was eight, my mum took me over to an old cafe in the neighborhood called South Hill Candy Shop and immediately I was overtaken by the music coming out of the speakers” he recalls. “It turned out to be “Halcyon” by Orbital, and I bugged the shit out of my mum about it until she finally asked the barista. He told us to come back in a day, and when we went back in he handed me a cassette with Underworld, Sneaker Pimps, The Orb, Orbital, Fluke and artists like that. It all started there”. Just before I compliment Campbell that it’s an adorable story, he continues, “South Hill Candy Shop burned to the ground about year later, actually” he notes, his emotion impossible to read over a computer.

Now 25, Campbell’s production work has extended over half his life, where he’s utilized DIY-programming tools and frequented forums for the last 13 years. Despite the longevity, his first experience of dance music is still clear in his head. “When I was eight, my mum took me over to an old cafe in the neighborhood called South Hill Candy Shop and immediately I was overtaken by the music coming out of the speakers” he recalls. “It turned out to be “Halcyon” by Orbital, and I bugged the shit out of my mum about it until she finally asked the barista. He told us to come back in a day, and when we went back in he handed me a cassette with Underworld, Sneaker Pimps, The Orb, Orbital, Fluke and artists like that. It all started there”. Just before I compliment Campbell that it’s an adorable story, he continues, “South Hill Candy Shop burned to the ground about year later, actually” he notes, his emotion impossible to read over a computer.

After first contact with dance music, Campbell’s interest spiralled into full-fledged obsession. As a child who grew up in a house full of computers with fairly early access to the internet, his web-scouring and downloading habits began as soon as technology facilitated it. But even before the internet provided a glimpse of dance culture outside the young Vancouverite’s hometown, Campbell recalls having preconceptions and glimpses of what the future held.

“Early on, I had this funny pre-formed idea of what raves were like” he laughs. “As an 11-year-old, I thought it was this really dark and mysterious place where people definitely did naughty things but also made dance music in the shadows. I wasn’t wholly far off.” Where did those ideas come from? I ask. “I think there was a loading screen from the software ‘rave ejay'” he responds. “…something about it was sinister.”

Though Much Less Normal is a collection of tracks evoking a dusky, last moments of summer sunset melancholic euphoria, Campbell’s work goes to those dark places as well. His collaborative release with fellow West Coast producer Boreal on Montreal’s hotly tipped Forbidden Planet label is a kinetic stormer of metallic energy; a surging breakbeat pressing to the front of the track which fits the record’s dystopian cover art by Paul Gondry (whose work ranges from vaguely unsettling to paralyzingly nightmarish). Showcasing a skyline claustrophobically crowded with skyscrapers and concrete streets packed with traffic, it’s a far cry from the watercolour tones and soothing rhythms that characterized Much Less Normal.

Though Much Less Normal is a collection of tracks evoking a dusky, last moments of summer sunset melancholic euphoria, Campbell’s work goes to those dark places as well. His collaborative release with fellow West Coast producer Boreal on Montreal’s hotly tipped Forbidden Planet label is a kinetic stormer of metallic energy; a surging breakbeat pressing to the front of the track which fits the record’s dystopian cover art by Paul Gondry (whose work ranges from vaguely unsettling to paralyzingly nightmarish). Showcasing a skyline claustrophobically crowded with skyscrapers and concrete streets packed with traffic, it’s a far cry from the watercolour tones and soothing rhythms that characterized Much Less Normal.

The same can be said for several of the slew of aliases Campbell has produced by over the years, such as his occult-referencing R.P Stoval moniker (a name taken from a string of code that Aleister Crowley insists a demon named Aiwass whispered into his ear when he was writing his famous work The Book of The Law). This project finds Campbell employing a harsh industrial palette with his work, sounding like soggy flesh hitting the grates of a factory floor. It’s one of several traces of Campbell’s persona strewn throughout the internet, and proof that Lnrdcroy is only one facet of his production personality. Dig deep enough, and you’ll find grainy YouTube footage of him flaunting a much more aggressive persona, playing old skool acid, UK hardcore classics and pre-1994 jungle in a nearly-pitch-black rave on the edge of town, camera permanently unstable because whoever’s holding it is dancing too hard.

Is Campbell purposefully keeping these different sides of himself segmented and locked away? It doesn’t appear so. “I appreciate the faceless techno thing, there is a mystique to it,” he says, but admits that he doesn’t want to approach the point of gimmickry. “I find excessive vanity to be a turn off in general; though a performer’s overall aesthetic force and display of ego, their image, can be quite powerful. It has the ability to create uncomfortable hierarchies like you get with big celebrities.” It’s a challenge that Campbell hasn’t had to confront yet, as he tells me “us little guys don’t have to worry about that though, thankfully.” Happy to let his creations flourish on their own, Campbell acknowledges that there’s a middle ground between anonymity and overexposure. “I can’t foresee myself doing sexy photo shoots or something to promote my next record,” he grins.

Still, never say never, right? After all, constant self-reinvention seems to be an integral part of Campbell’s persona. As mentioned above, Campbell’s goal for a string of upcoming live sets is a lofty one – creating a series of sets composed entirely of new material. “Basically, with the advent of my live show, instead of working on one tune over the course of a week or two, I am constantly working on five or six all in the same project,” he elaborates. As a result, the work takes on a certain synchronicity, with each individual track feeding into and informing others. “I get obsessive about something and my output becomes this holistic reflection of that,” he admits.

But perhaps because of a near-constant immersion in the studio, Campbell has come to citing failure and mistakes as things to embrace. “Recently, an acquaintance of mine introduced me to the concept of ‘wabi sabi’, a Japanese aesthetic that sees beauty in impermanence, incompletion, and imperfection,” he confides. “I’m fascinated at this from a creative standpoint – I feel like I’ve suffered under the pressure of standards and formulae for too long, and there’ve been too many things that end up getting abandoned because it didn’t sync up with my preconceptions. I’m starting to see that the struggle of making music is just as important as the end result…”

Playing live sets seems to embody this same ideology, placing importance on process and interaction. “Ideally, it’s a way to communicate with people because the studio process is typically very self-indulgent. Performing live allows me to give something back in a present way,” he admits. “It’s about as live as my studio recordings, which are live jams. I come up with each individual element and the improvisation comes with the general composition. I spend time refining the bricks, but how I end up building the house is rather free-form. Overall, it’s fairly choreographed… with a few options on the side for each.”

Much Less Normal is bursting with a much more improvisational tone, the entire album gelling together as the result of three distinct studio sessions. “Almost every recording I do is a straight-to-stereo recording with no multi-tracking or anything like that,” he tells me. “I will often hear something I like in an older tune and resample it; I’ve made the important step of saving my sounds instead of starting with a fresh slate every time. There’s a constant transmutation going on, where everything gets recycled and refined.” Campbell seems almost unsure how the work came about himself, referring to it only semi-jokingly as a “pastoral vision”, and throwing around words like “playful” and “naive” to describe it. “I’m constantly impressed by my West Coast environs, and I suppose Much Less Normal represents this – a longing for nature, while still being bound by the city and its trappings,” he acknowledges.

Once you start looking for it, Much Less Normal is abundant with imagery that evokes British Columbia’s coastal moodiness. “I Met You On BC Ferries” begins with a rolling Balearic placidity, but slowly the subdued percussive patterns explode and blossom into a full-formed  climax that feels like the track has finally bobbed up for air after being immersed in the deep black water of the Pacific. Meanwhile, the “Live Mix” of “Telegraph My Love” utilizes vigorous techno pinpricks with sweeping ambient tones blowing through it like the first gusts of wind before an oncoming storm, and “Sunrise Market” evokes stumbling through downtown Vancouver post-rave, when the mid-morning sun is already blindingly high and bright in the sky.

climax that feels like the track has finally bobbed up for air after being immersed in the deep black water of the Pacific. Meanwhile, the “Live Mix” of “Telegraph My Love” utilizes vigorous techno pinpricks with sweeping ambient tones blowing through it like the first gusts of wind before an oncoming storm, and “Sunrise Market” evokes stumbling through downtown Vancouver post-rave, when the mid-morning sun is already blindingly high and bright in the sky.

Speaking to 1080p label boss Rich MacFarlane, he cites Campbell’s work as one of his favourite releases on the label, “not only because it’s so exact in its examinations of landscapes and neighbourhoods here in British Columbia but also from the idiosyncrasies that come with along with classic ambient electronica touchstones.”

“Much Less Normal has (for real) affected a lot of people here in Vancouver, I think for touching on some vaguely collective sensation of what it feels like to live here,” MacFarlane believes. “There are big, vivid nostalgias backing these tracks with looks towards funny culturally embedded Canadian things”, he explains, citing the Slam City Jam skateboarding competition that Croy titles one of his tracks after, to BC Ferries and neighbourhood grocery stores.

The appeal extends beyond British Columbia residents: Much Less Normal can’t stay in stock at the 1080p website, selling out days after the label re-releases a new batch. While Campbell admits that “how music is delivered and consumed of course has an effect on the user experience,” he doesn’t produce for a particular format. “I do appreciate physicality, however,” he adds. “I grew up listening to MP3s that were ripped from a hard format; you can still hear the tape hiss or the vinyl surface noise in there. I am a child of the times. I like the idea of an artefact at the origins of the sound. There is something very satisfying seeing a song you make end up as an object to behold.”

Still, Lnrdcroy isn’t a purist project when it comes to technology. “There are no analog instruments in my studio besides an SH-101 that I borrowed from a friend,” he admits. “My setup consists of digital hardware; samplers, keyboards and effects, and up until about five or six years ago, I only produced using a computer. I’m still using the computer for processing and some synthesis, but it always gets transferred over to one of my samplers for further use. I’ve kinda refined my hardware setup and have decided that there isn’t much else I would add or subtract to it. I couldn’t ask for anything more in terms of workflow. Just the right amount of limitations are in place. I’ve been using the computer like I would use a studio – instead of writing songs, I’d just jam out patterns until a story formed.”

While fellow BC label Mood Hut has an enduring aesthetic that it refines with each new addition to its catalogue (as well as endless variations of faux-antiquated photocopied rave flyers and record sleeves that look like they’ve been pulled from a basement storage unit from 1993), Lnrdcroy seems agile with his stylistic obsessions, which he admits tend to move in cycles. “I’ll chase down a certain sound, style, or trope until I hit a wall,” he muses. “Right now, I’m thinking about the concept of ‘wildstyle’ and how early ’90s hip hop and old skool UK hardcore/junglist vibes go well together.” Several days after, he sends me an improvisational organ solo from Keith Jarrett’s album Hymns/Spheres, citing it as the track he most wishes he made, and describing it as “particularly transcendental, holy, sorrowful, frightening, and full of joy”.

But despite his multitude of inspiration, there’s never a moment in my conversation with Campbell where he seems insincere – instead, there’s a moral cohesiveness to his production that feels rare in the days of genre-grab bags; something enduringly genuine about Lnrdcroy’s fascination with rave culture. Campbell’s music taps into that same naive pre-exposure optimism – the potential for euphoric moments, for dancing your way to a better future, for dancing the conflict out of yourself.

After Campbell and I say our goodbyes and log off, I bike to work past Toronto’s Digital Dreams festival, Canada’s largest EDM event. In a moment of curiosity I gaze through the fence separating the festival from the bike path, and see thousands of floral-headdress and shutter shade-clad ravers condensed into this tiny space, collectively jump-thrashing to boisterous drops and breakdowns. Instead of smirking, I think about how many likely came from hours away, from small towns without rave epicentres. The beer company ads covering every inch of the festival may seem tacky to me, but it might signify the promised land to them. Lnrdcroy will be playing at Vancouver’s New Forms Festival later this month alongside DJ Sotofett, Helena Hauff, SVN and Inga Copeland and more. While it will be worlds apart from an EDM festival, when it comes down to it, both events are just looking to carve out the little piece of rave utopia that we all heard was promised to us once we got older.

Interview by Brendan Arnott