Separate Mind: Detroit – Home of House?

Richard Brophy assesses the current state of Detroit’s house music scene, with contributions from Mike Huckaby, Patrice Scott, MGUN and more.

Detroit. For many people in electronic music, the American city’s name sounds incomplete if it’s not said in the same breath as techno. The reason why Detroit techno has become so engrained in electronic music is due to the legacy of Derrick May, Juan Atkins and Kevin Saunderson and the many waves of producers that appeared in their wake from the early ’90s onwards. Without Detroit, techno would not have developed in the way it did. A techno world without any of the characteristics associated with the Detroit sound – depth, melody, groove – would be a bleak place, conveyor belt tracks and a soul-less jackboot stomp.

But the city isn’t just known for techno; along with Miami and New York it spawned electro, introducing the mighty Drexciya and their many different aliases to the world, as well as artists like Aux 88, Adult and DJ Stingray. Its faster, more abrasive sound, ghetto-tech, has also enjoyed a steady following at home and abroad, and DJ Stingray gave a fascinating insight into that scene a few years back on Juno Plus. Then there’s the city’s house music. Labels like KMS and Harmonie Park trace their roots back to the early ’90s, as do artists like Rick Wade, Rick Wilhite and Mike Huckaby. DJs who later became revered house producers – Patrice Scott, members of the Beatdown crew – were spinning since the ’80s. And yet despite this rich heritage, one that Moodymann and Theo Parrish have built on in spectacular fashion, Detroit’s allure and influence abroad is largely still as a techno city. Why is this?

The irony is that the work of some of the city’s main techno artists was heavily indebted to house music. Listen to the early releases of Kevin Saunderson, Blake Baxter and Eddie Fowlkes and it’s clear that they sit at the edges of techno and house, the soulful vocals and primal rhythms more earthy than Detroit techno’s ethereal sensibilities. Also, pioneering Detroit DJs like Ken Collier or the Beatdown DJs didn’t make any distinction between house, techno or disco. Despite this, Detroit is known as a techno city and Chicago is forever associated with house.

This was down to selling music to audiences outside of both cities; when Detroit artists first signed to European labels, their sound needed a brand name to set it apart, as did their Chicago counterparts. Although Jeff Mills’ bone-crushing Waveform Transmissions inhabits a different universe to Inner City’s Pennies from Heaven, they are sold under the same banner. Since then, Kenny Dixon Jnr, Theo Parrish and Omar S have all introduced a distinctive Detroit house sound to the world. Over the past year, there have been a series of benchmark releases that showcase the fact that the city is as much of a home to house as techno.

These include stellar albums from Moodymann and Omar S, but also the raw swing of Kyle Hall’s debut album The Boat Party, Andres’ sublime soul, MGUN’s freeform amalgamation of beat tracks, wiry techno and electro for a variety of labels and Jay Daniel’s two excellent EPs of rough, earthy grooves for Sound Signature and Wild Oats. Meanwhile, Still Music celebrated Detroit house’s deeper side with its excellent In The Dark: Detroit is Back compilation issued late last year. Featuring established house heads like Mike Clark and Reggie Dokes alongside DJ/producers like Raybone Jones who are only known in their home city, it is to be followed by the release of Patrice Scott’s debut artist album, due later this year.

Set against this backdrop; is it still fair or accurate to call Detroit a techno city? “I’d argue that in terms of artists currently making music, it already is as well known for house as techno,” says long-term Detroit music fan, DJ and one-third of Pittsburgh Track Authority, Thomas Cox. “Right now guys like KDJ and Theo Parrish are just huge. Sadly, it seems like most of the most well-known Detroit techno producers are either no longer living in Detroit – Jeff Mills, Robert Hood, Octave One, Claude Young – or are not nearly as prolific as they once were – Underground Resistance, Anthony Shake Shakir, and Suburban Knight. In general, it seems like there is a wide variety of parties going on in Detroit that are associated around house and disco along with some techno, but not so many straight up banging techno parties.”

Jerome Derradji, who runs the Still Music label, says that his motivation for putting out In the Dark was down to his passion for Detroit music rather than trying to push house music per se. “I’ve always felt really strongly about the quality of music that is made in the D. It’s a thriving scene and all the guys there are like a big family to me. Supporting Detroit and the scene there is important and natural to me,” he says. Derradji believes that new school artists Jay Daniel and MGUN and late bloomers like Patrice Scott incorporating techno and electro tropes into their grooves is part of an evolution process.

“Detroit will always been known as a techno city, but it is all evolving, so maybe it’s techno that is a bit slower or deeper (like the beat down stuff sometimes). The music coming out of Detroit is cohesive and is logically coming from a long tradition in electronic music, disco, boogie, electro, house, techno, hip hop, ghetto tech, you name it,” he says. From a DJing perspective, this approach is part of the city’s musical past. The ‘beatdown’ style was a composite of many different sounds, while Electrifying Mojo, who is held up as the DJ inspiration for the first wave of techno artists from Detroit, also appealed to the house heads.

“Based on the guys I know, there isn’t any difference. KDJ did a record with samples of Mojo talking to Prince, Kai Alce did a whole series of records in dedication to the Music Institute,” says Cox, while Jerome adds: “Electrifying Mojo and the Music Institute inspired everybody, the techno guys, the house guys and the hip hop guys. There is no separation between house, techno and hip hop in Detroit. It’s part of the city’s heritage and its artists are always collaborating together, they make all kinds of music, be it house, techno, hip hop and soul. Take what Rick Wilhite says in the In The Dark documentary when he talks about Juan Atkins. ‘We just got together and tried this thing’. That gives you the spirit of Detroit right there.”

In this regard, it’s interesting to hear a newer house artist talk about his musical influences and where he sourced them. “It’s all across the board when it comes to what inspires me to make music,” says Manuel Gonzales aka MGUN. ”My interest in music was initially introduced to me by what was on the radio and what was played in my house. I was too young to go to clubs and I didn’t become aware of labels until I was a little bit older and would investigate a track I liked.” Gonzales’ music is an unusual, at times hyperactive mish-mash and his releases on Wild Oats, Don’t Be Afraid and The Trilogy Tapes could be loosely described as house.

“One of the best parts about living in Detroit is the access to a rich musical catalogue and I can say that listening to all kinds of DJs was inspiring because each one approached the tables differently,” Gonzales says, explaining his background. In a city full of great DJs, some known and others not so  known – more about that later – there is one person that every contributor to this article cites as an influence on the city’s house scene: the late Ken Collier. The Heaven resident died in 1996 and on his passing, Aaron Carl – another Detroit artist who also died a few years ago – said: “Ken Collier is the man who turned me onto house music. He is the man who taught me (both directly and indirectly) what it is to feel the music. He brought us together in a way that nobody else could – black, white, straight, gay, whatever…”

known – more about that later – there is one person that every contributor to this article cites as an influence on the city’s house scene: the late Ken Collier. The Heaven resident died in 1996 and on his passing, Aaron Carl – another Detroit artist who also died a few years ago – said: “Ken Collier is the man who turned me onto house music. He is the man who taught me (both directly and indirectly) what it is to feel the music. He brought us together in a way that nobody else could – black, white, straight, gay, whatever…”

Mike Huckaby, who has been releasing deep house music since the mid-90s, agrees that Collier’s impact on the city’s DJs was profound. “Ken was the premiere DJ in Detroit – a lot of people adapted to his style of mixing; his DJing became a reference for mixing and beat matching. He played across the board, house, disco, techno.”

Collier’s approach is still audible today in what Huckaby terms the city’s ‘long-time players’. Instead of going down the pre-meditated route of producing records to gain international recognition and bookings, many of the city’s house DJs take their time, which allows them time to develop their production skills. Huckaby says that he was lucky his first few releases on Deep Transportation sold so well and he continues to repress them to this day. For some of his peers, the situation is different.

“You gotta understand that there are a lot of Detroit DJs who don’t want to play the game and are content to play regularly here,” he explains. “I mean there are a lot of guys in Detroit who haven’t played some of the big festivals because they don’t want to put out tracks. It’s a Catch-22 situation, they aren’t as widely known as some producers, but don’t want to have a DJ career based on their productions,” he believes.

Thomas Cox also points out that “someone like Norm Talley had 100 plus self-released house mix CDs for sale in the city back in the days when such things were done. He was doing his thing in Detroit, and putting out less records than maybe he is now”.

“It’s not all down to just what we see from outside – someone like Raybone Jones only has a couple records out, but he is hustling in the city playing gigs,” Cox adds.

Patrice Scott has been DJing in Detroit since the ’80s, but only started to take production more seriously in the late ’90s when his day job slowed down. “I wasn’t really known as a DJ outside the Detroit area and I was always just interested in playing records. I never thought about production,” he says. As to Scott’s influences, he cites Hotmix 5 – “I used to sit back and study how they knew their records. They used to mix records from the break, you don’t hear that anymore” – as well as Electrifying Mojo – “I know you have heard this a million times”.

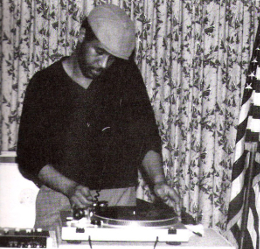

Polite and considered over Skype, Scott (pictured above) is also modest about the series of deeply musical, atmospheric house records that he has released almost exclusively on his Sistrum label since 2006. Mike Huckaby believes that Scott, Norm Talley and Delano Smith personify the concept of Detroit DJs turning into respected house producers later on in life.

Polite and considered over Skype, Scott (pictured above) is also modest about the series of deeply musical, atmospheric house records that he has released almost exclusively on his Sistrum label since 2006. Mike Huckaby believes that Scott, Norm Talley and Delano Smith personify the concept of Detroit DJs turning into respected house producers later on in life.

“The DJs making house music from Detroit are drawing on their extensive knowledge of music from Chicago, Detroit and New York. These guys have a well-developed ear – they know house and techno inside out. It’s a bit of cliché to say that Detroit DJs aren’t influenced by anything. We are influenced by everything and we interpret it in our own way,” he believes.

For Scott, the interpretation is borne from his love of Chicago house and deep Detroit techno. Listen to his releases and you can hear the dreamy textures of early Carl Craig or the percussive punch of Ron Trent, re-engineered and refined. “I try to make music at between 125-130bpm. If it goes any higher, it gets erratic,” he laughs. “Early on, Chicago house was a big influence rather than Detroit, but like a lot of house coming from the city now, my music is techno-influenced. Techno doesn’t have to be fast and I like emotive music, I can’t hear tracks that say the same thing for eight minutes.”

Scott says that his debut album, which is ’99.99 % coming out in 2014’, will include stripped back jams, vocal tracks and deeper techno. There is a big sonic difference between Scott’s introspective sound and the raw, brash drum tracks that younger Detroit house artists like Kyle Hall, Jay Daniel and MGUN make. In effect, is Scott just producing a slower version of Detroit techno – and were the lines always this blurred?

“It’s a myth to say that house DJs weren’t influenced by techno producers and the other way around,” says Huckaby. “They [Detroit house and techno] are mostly one and the same,” Cox believes. “Listen to Eddie Fowlkes’ early records on Metroplex, or Blake Baxter’s records from the ’80s and tell me those are not house music. To me, “Strings of Life” is just as much house music as it is techno. Mad Mike’s stable of labels included Happy Records, which was banging out deep and vocal house music at the same time he was leading techno into new places with UR. It mostly was never so cut and dry in Detroit. Derrick, Juan and Kevin would go to Chicago to check out Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hardy. Kevin also spent time in NYC listening to house and garage. Even guys like Shake were taking trips to Chicago and listening to the Hot Mix 5 on cassette tapes. Techno really started out coming from mostly the same places as house, just a slightly different take with more influence from funk and electro. It wasn’t until a bit later that the more looped banger format of techno became a thing.”

And yet despite these producers’ early dalliances with other scenes, Detroit techno continues to play a role in the city’s house music. Jay Daniel’s new record, the wonderful Karmatic Equations on Wild Oats, is peppered with the kind of sub-sonic outer space blips and bleeps you’d find on an Underground Resistance track, while MGUN’s Some Tracks on Third Ear from 2013 seethes with ghetto and electro edginess. “People here draw inspiration and influence from many different sources – for me it’s Atkins, DJ Assault, Gary Chandler and guys that played on FM98 WJLB. DJ Assault and the guys on the radio played electro, house, techno, jungle and booty records in their mixes. Juan Atkins and UR provide the true essence of Detroit techno, while Moodymann and Theo Parrish provide Detroit’s deep house productions,” says Manuel Gonzales.

Thomas Cox posits the theory that there hasn’t been much new techno from Detroit in recent years because most of its main practitioners moved abroad for work reasons, while many of the house DJs remain in the city. Despite this, he feels that for some artists, out of sight does not mean out of mind. “The thing about Juan Atkins is that his music is everywhere in Detroit. More so than any of the other old techno guys, his music is just part of the fabric of the city in ways that it’s tough to understand without spending some time there. You can drive past family parties on Belle Isle on a summer day and they are banging Cybotron or Model 500 along with rap and R&B,” he explains, adding that “I’m sure there are people in Detroit who are influenced by the newer crop of producers and DJs, but most likely that would be a result of those people being online.”

Jerome Derradji agrees that ‘all the big cats’ remain an influence because they built Detroit’s unique sound. “Their success is an inspiration to many. The beauty of it all is that all these bigger names are supporting their own scene and always pushing for young Detroit artists to come out with new music and projects. It’s pretty unique to Detroit,” he says. Despite a new wave of house producers coming up through the ranks, there is not much infrastructure to support them. With no dedicated club and fewer record stores than before, it poses questions about what the future holds for Detroit’s music scene. Mike Huckaby believes that one of the reasons why house veterans like Patrice Scott make such great music is because they were “fed a steady diet of great records and that spills into a producer’s personality and influences the type of music that they make”.

Derradji and Huckaby both cite Detroit Threads as a store stocking good Detroit vinyl, but Thomas Cox is less upbeat in his assessment of Detroit record stores. “Rick Wilhite’s Vibes record shop was kind of that hub back in the day, but now it seems like there is no one spot. The record shops there are not what they once were in the days of Record Time [where Huckaby used to work], so the ability to just come up on these records is less than you might think. Once you know to look for them, there are places to go get them, but to me that distinction is pretty big. You’re definitely much more likely to find Wild Oats, FXHE, and Sound Signature records at any store in Detroit than any of the older stuff.”

The TV Bar and Motorcity Wine venues support house music, while the city is still home to a lot of loft parties, but one of the hardest blows to Detroit’s electronic music community came last month when the 1217 Griswold inhabitants had eviction orders served on them by the building’s new owner, billionaire Dan Gilbert. “It had become an epicentre for good, raw Detroit house and techno. Unfortunately, it was recently purchased by some dickhead who is evicting all of the current artist residents, so he can build a centre for artists,” says Manuel Gonzales.

Yet despite this development, Detroit house music will continue to thrive. Thomas Cox gets the sense that the city is moving forward and that downtown Detroit ‘isn’t the ghost town it was before’, but Derradji feels that the economic situation hasn’t improved and Detroit is a poorer place now than when techno emerged during the late ’80s. Ironically, Detroit’s financial bankruptcy hasn’t drained its creativity and limited options have turned into opportunities.

“Right now, much like all over the US, the technological gap between whites and African Americans is really big. That means that sometimes – in Detroit – music is the only way to make a decent living as all the doors for better jobs are closed and not accessible to a huge part of the population,” he says. Patrice Scott adds that creativity will also rise to the surface in the Motor City and the recession means it is cheaper for artists to live there. “Detroit has always been creative, a place where great music and other art forms came from. It’s hard to say if the recession opens a door for Detroit, but maybe now more creative people are looking at it and saying ‘I can live the dream’.”

Let’s leave the last word to Manuel Gonzales, one of the new of producers who is bringing Detroit house music to new places.

“You can’t classify Detroit as a house or a techno city – it’s just a music city,” he says.

Amen to that.

Richard Brophy

Header image used courtesty of The Trilogy Tapes