Five Records: The Eyes In The Heat

As The Eyes In The Heat, Oliver Ho and Zizi Kanaan come loaded with intriguing cultural reference points – their Jackson Pollock alluding name alone hints at them using the project to abandon musical conventions. Their debut album Program Me arrives this week and upon first listen it seems perfectly at home on Ivan Smagghe’s Kill The DJ imprint, with lead single “Amateur” typical of the spiky sonic Gallic swagger the label has nurtured over the years; “Techno not Techno, Rock not Rock” as they put it.

Yet beyond that, there are strangely addictive diversions that present the band to have wider influences and tastes, such as “Perfect Gun” which recontextualizes MC 900 Ft Jesus’ “Dali’s Handgun” as a Teutonic Synth Wave delight or “Stare” which demonstrates the full range of Kanaan’s vocal delivery in under five minutes. As a whole the noirish electronic pop of Program Me presents an interesting new side to Oliver Ho, with subtle remnants of his sizeable past as a techno producer present throughout, but it’s steadfastly a joint vision between himself and Kanaan.

With this in mind, they felt a perfect fit to inaugurate the new Five Records series at Juno Plus wherein artists are invited to discuss, yep, five records that resonate deeply with them. Aaron Coultate spoke to Zizi and Oliver about some treasured records in their respective collections, with the selections spanning African funk, avant-garde tinged pop and classic grindcore.

1. Ghana Soundz – Soundway compilation (2002, chosen by Zizi Kanaan)

Hi Zizi, so why did you pick this LP?

ZK: I picked this because it’s had quite a strong influence on me. I really love poly-rhythmic music and the tracks on this compilation have this extremely dancey, hypnotic feel, with these strange psychedelic synth solos that come in. Obviously synths in the 70s and 80s in Ghana weren’t really commonplace, so they used fairly basic organs which sound dry and strange but somehow amazing. I know Miles Cleret, who runs Soundway, and it was one of the first records he released. For me, it was one of my first entry points into funk.

Miles travelled all over the place to find those records – some of them were fetching crazy money among collectors

ZK: He’s got an incredible record collection. He’s so knowledgeable and I’m glad to see the label doing well. The limitations when this music was being made, I can sort of relate to. When you have restrictions on what you can use and what you can do and how you can record things, it ends up affecting the music you make. These days there are endless possibilities with making music, especially electronic music, and it’s overwhelming. I like this idea of limitation. A lot of the music on this LP was created on borderlands, places with no rules on what you could do or could make, and many musicians were living in the midst of a violent or oppressive culture.

You talk about people making the bets of what they have – for The Eyes In The Heat two influences that come to mind are techno and DIY post-punk – two areas of music with a history of using limited, often cumbersome gear to creative ends. Did you guys set your own markers when making Program Me?

ZK: Yeah, absolutely, we try to keep that ideology. Oliver has grown up with that aesthetic and that idea. You can overwhelm music with technology – stripping it down to essentials is really important to me. It’s about using sounds that aren’t necessarily super high tech or smooth, using instruments you know well and sounds you know well. You can do a lot with a very simple sound. A lot of the other stuff is just distraction – you get caught up in the constant renewal of sound and it doesn’t help. If you want to get to the essence of something, you need to meditatively hone in. The whole aesthetic of DIY is important – if you bring in too much from the outside it distills your sound and your identity. It’s meditation – you get to know the song, things develop, it becomes clear what you’re looking for and what you want. It’s a natural and spontaneous process. You can feel it when song starts finding its home, and you suddenly can’t imagine hearing it any other way.

2. Laurie Anderson – Big Science (1982, chosen by Zizi Kanaan)

Tell me about this album – what kind of influence did it have on you?

ZK: This is an extremely rich album, full of space, and a minimal funk aspect to it, with these soaring solos and an interesting use of violin, which I played when I was growing up. It was developed through the practice of installations and live performance – the sounds can sit easily on the album but the feel equally comfortable with a visual counterpart. They are quite precise.

She fits in with that amazing era of New York based multi-disciplinary artists in the 1970s. The performance art element to he was evident on the video for “O Superman”…

ZK: Yes, that is all about body language on that clip. I love her very direct, extremely astute observations about industrialisation and commercialisation. She has this ironic, wry, weird wit. I have these anxieties as someone who lives in a city or urban environment, over buildings and concrete taking over. Coming from Lebanon, which is full of unconsidered mass construction, especially around Beirut, and there’s very little flat land. It’s just layer upon layer of concrete. Big Science for me pinpoints that strange, menacing, dreamlike feeling of buildings closing in on you.

She did an interesting collaboration with William Burroughs that came out before this album.

ZK: William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg too, were a particular influence on the way she writes her lyrics. In somewhere where the surrounding environment is huge, like the US, the sense of being overridden by buildings and people is even more extreme; you see these huge shopping malls and developments bearing down on you.

Her politically and socially aware commentary took its cues from the beat generation.

ZK: I think that is missing from music these days – an ironic take on the world. The views are extremely personal but there not about the “I” or the “you”, but everyone. They really hit that feeling of anxiety. I love the way Laurie uses her voice. She doesn’t use it typically; I’m bored of singers in the traditional sense. It’s more important to use your voice, but you don’t have to sing. You can speak, you can sing when it’s important or when you feel like it, but not always. It’s a female thing – you are told that you have to sing and you have to sing in tune. I want to move away from that cage and use my voice as an instrument. I love the way Laurie does both – one minute she’s talking and asking questions wryly, then she’s sounding very sweet and solemn. She pitch shifts her voice, which is very fashionable now, but not so when the album was first released. As a vocalist I’m inspired by the dustiness of an untrained voice; I don’t like too much precision. The untrained voice brings with it a lot of character of a person, and training can delete that. That’s why I love the speaking voice being recorded – you can hear all the subtle intonations of a person’s character.

It’s hard to escape the feeling that this album was so ahead of its time, both lyrically and sonically.

ZK: Well I get that feeling from the title track in particular it sounds like a Hindu chant – which is so relevant now, in the way that science is worshipped like a religion.

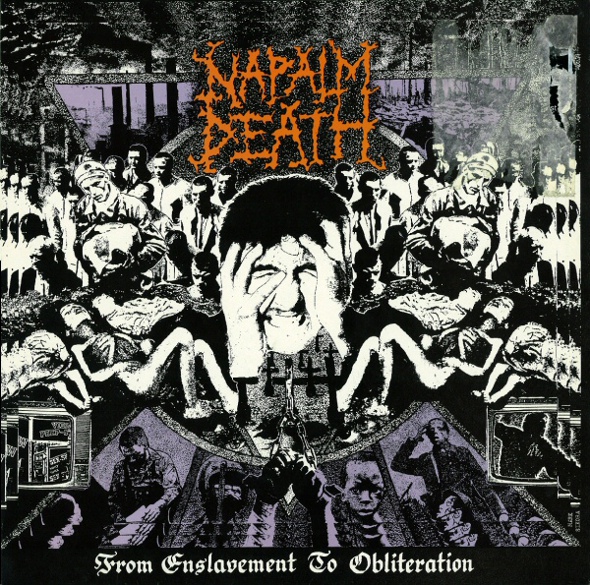

3. Napalm Death- Enslavement To Obliteration (1988, chosen by Oliver Ho)

Hi Oliver, tell us – when did you first hear this album?

OH: The first time I heard Napalm Death was 1988 or 89. I saw them live around the time the album came out – I must have been about 14. It was one of the first gigs I ever went to. I remember hearing them on the John Peel show, that I was religiously listening to at that time, like everyone else. He’d be playing obscure tracks from The Fall into African pop music and a lot of death metal and hardcore punk and following the emergence of British grindcore. This album had a huge influence on me as a type of music that hadn’t been around before. It sounded new and really exotic at the time.

It was pushing new sonic boundaries, wasn’t it?

OH: It was music being made for the first time by people who weren’t really sure what they were doing. They captured this energy and it was irresistible – there was no reference point for it. It’s rare to hear something these days and think, “Oh my God, what is that”, because we live in such a post-music world in a way, where a new genre gets created every five seconds. This album had a massive effect on me, and it was similar to the time I first heard techno music too, which sounded very alien.

Did you go to many more death metal gigs around this time?

OH: Yeah. The first one was Napalm Death at the University Of London. I was seeing bands like Extreme Noise Terror, Carcass, bands linked to Earache Records. They were all doing Peel Sessions at the time too.

That kind of raw, visceral music is best experienced live.

OH: I don’t think you can really understand it unless you’ve heard it live. It needs to be at a horrendously loud volume – it becomes physical. That’s the thing about live music in general – you actually feel the volume and vibrations physically. Being so young and scared at these gigs – I was much younger than most of the people in the audience – added to the intensity and magic of the whole experience.

You made the comparison between hearing Napalm Death for the first time and discovering techno – it’s interesting that Mick Harris of Napalm Death is someone who’s turned to electronic music, having remixed material on your label and worked with Karl O’Connor.

OH: It’s been a long journey from seeing his band all those years ago to having an almost parallel progression and both of us ending up in electronic music.

In terms of the sheer sonic force of Enslavement To Obliteration, did you bring it to your early techno productions?

OH: Certainly, I tried to bring that density to my early music. There is definitely a link. The purity and attitude of this album still appeals to me, and I find myself returning to it still. I listened to it quite a lot this summer. It perhaps doesn’t show its influence in my music sonically any more but it’s stayed inside me all these years.

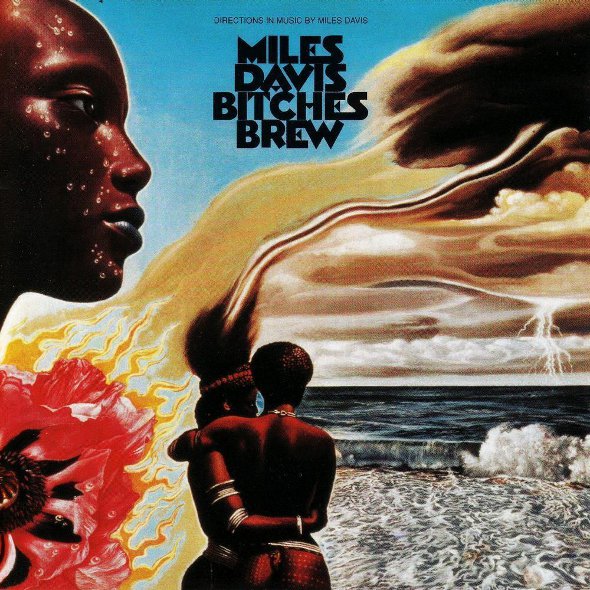

4. Miles Davis – Bitches Brew (1970, chosen by Oliver Ho)

What kind of impact has this record had on you as a musician and as a person?

OH: I went through a phase of listening to a lot of Miles Davis, but it was this album that cemented him for me as a genius, because of the texture and the space within the music, and also what he was doing with jazz as an artform at this time. This was an era when electric fusion was a new thing, it was a crossover period in jazz when it was going from bebop and traditional forms into rock and avant garde-influenced stuff, which is where Bitches Brew fits. Hearing this music that was at the cusp of new territory, you can feel that here. You can feel him searching and fusing things and ideas together. The way he fuses monotonous rock rhythms with very avant garde sounding organs and free jazz horn sections is amazing. The way he fused them has certainly informed some of my more recent forays into music as Raudive – I try not to be too clear and leave a feeling of something trying to find its place.

At what stage in your life did you get introduced to the music of Miles Davis?

OH: I would have been in my mid to late 20s when I first heard this album. It had a really big impact on my music at the time; it made me want to explore broader musical ideas and allow those ideas space to move into different directions.

By that stage you had already released 12″s with Blueprint right?

OH: Yeah. This was the around time I was running Meta. On Blueprint I was focusing on darker, more electronic stuff and then with Meta I started making tribal and jazz influenced stuff. I was really into using African chanting and vocal elements.

With your canon of music now, I don’t think you could be accused of not taking your sound in a number of directions.

OH: That’s something fuels and inspires me. It makes sense to me although I don’t expect others to all have the same attitude, and I have great respect for people who are very obsessed about one type of music – some of my favourite artists are quite one-track in their mentality. But I think you can work with different ideas – techno, house, disco or rock music are not mutually exclusive things, and they don’t cancel each other out. I see a real consistency in the things I do even though they sound quite different to each other.

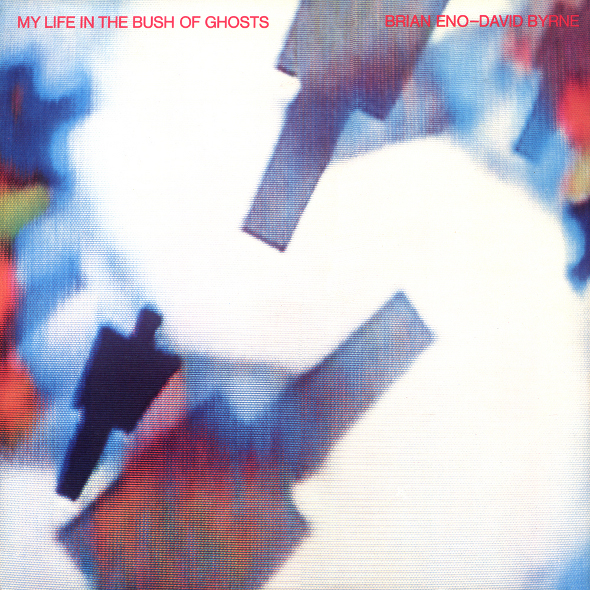

5. Brian Eno & David Byrne – My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts (1981, chosen by Oliver Ho)

You’ve said in the past Brian Eno’s approach has impacted on you – why exactly is this?

OH: I love the way he approaches different artistic disciplines be it pop music, experimental music or fine art, with the same internal quality control and attitude towards ideas. It’s the idea that it’s the individual who provides the signature rather than any overriding sound.

This record is littered with potential reference points for electronic music producers.

OH: I remember listening to this before passing out from listening to Napalm Death all day long. I had no idea what it was when I bought it – I hadn’t heard of Brian Eno or David Byrne; I knew of Talking Heads but didn’t know Byrne by name. Hearing this samplers used in that way for the first time was important for me, and their sound collage approach, the way they’d get a lot of different ideas – African rhythms, Arabic vocals, European electronics and typical funk grooves – was revelatory for me. It enabled my musical head to expand.

For an LP that is steeped in avant garde concepts, it can be easy to forget that it’s really, really funky. You used tribal rhythms in your techno productions – was this album a catalyst to you doing that?

OH: I would think so, yes. This along with hearing a lot of Japanese music. With My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts, some of the ideas are quite avant garde and some are quite pop. That’s something both Brian Eno and David Byrne are really good at and it’s something I’m really interested in. This kind of contrast, the way pop and avant garde ideas can work side by side… Eno managed to do this with lots of his solo stuff and also Roxy Music, and Byrne with Talking Heads. It’s this idea that you can have something that superficially contradicts itself but at the same time makes sense and remains interesting.

I remember reading that on this album they set up a standard drum kit but used a cardboard box for a bass drum and a frying pan instead of a snare.

OH: You create a tension in the music when you have these seemingly opposing ideas at play. And that’s something we’re trying to achieve with The Eyes In The Heat; we experiment with using quite dirty and techno-y sounds to explore pop ideas and create dark, electronic pop music. As it’s the first record we’ve done, there’s an experimental “let’s see how this works” mentality, and for me it’s been very interesting and liberating. It’s music that’s not easy to pigeon hole.