Subtitles, synthesizers and a cult of assassins: A Q&A with Jorge Velez

The output of New York based producer Jorge Velez exists on the fringes of the electronic music scene, inhabiting a world of limited run CD-Rs, occasional 7″s and a handful of scattered releases on various labels under various names. Unearthing his material, be it as Professor Genius, Duermo or one half of Bim Marx, is a reward for those who search for their music rather than let it come to them. To this point press coverage on Velez has been minimal, save for some fuss over his early Professor Genius material, released just as the Italians Do It Better label inadvertently kick-started an Italo revival of sorts.

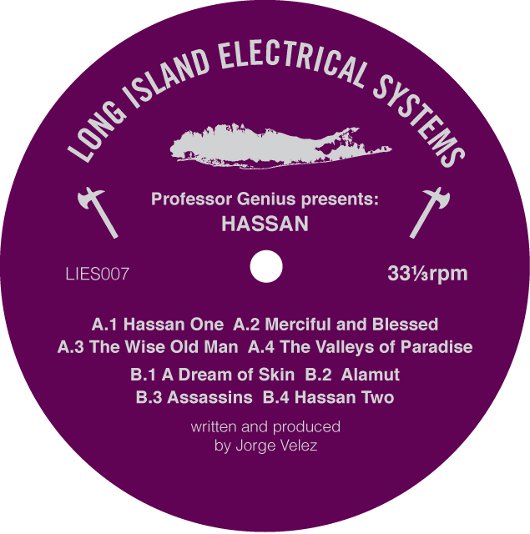

Associating Velez solely with Mike Simonetti’s imprint is of course selling him short; it’s more accurate to portray him as a DIY producer in the truest sense, self releasing much of his material in small quantities. A long time cinephile who has carved a career as a video editor as well as a self-taught synthesizer boffin, it’s no surprise Velez’s latest musical venture, Hassan, combines his two loves, scoring an imaginary film about a cult of assassins in 13th century Persia. The release was due out on Ron Morelli’s Long Island Electrical Systems label last year, but a series of vinyl pressing issues has plagued the album and delayed the album’s release.

One can only hope that when Hassan does finally see the light of day, Velez will get his dues – in the meantime we sent out New York correspondent Nik Mercer over to the producer’s Jersey abode to discuss his uncompromising approach to releasing music, his involvement in the mail-art scene and the story behind Hassan…

What do you do for a job – you work in film right?

Video editing for reality TV. It’s how I make my living. Until the day comes when I can start scoring movies (and that’s not going to happen!), that’s what I do. But I enjoy it.

Did you go to school for film?

No, I went to art school. I’ve always done visual stuff, since I was a little kid. I listen to lots of music while drawing, so the visual thing has always been there with my music; they go hand-in-hand. When I got out of school, I ended up working at a photo agency and became a photo editor. When that job ended, I wound up working at a recording studio, where they did a lot of music for commercials. It was a little studio in the Meatpacking District before it got really gross over there. I was an assistant engineer and learned a lot[about the trade.

By this point, I was already making my music at home, recording in my bedroom. But I learned how to mic a guitar, and how to mic congas, and how to mic people… that was great. At the same time while I was there, they had a little editing room set up, and we would do stuff for ad agencies―we’d have to edit commercials that we did music for and send it out to the agencies. So I had to learn how to use Final Cut―early Final Cut. I’ve always been a film buff and was like, ‘Boy, I’d really love to do this for a living, but I have to go to school.’ Anyway, that job ended, and I was kind of floating around. By that time, I was in a band. The band and I had made an album, and we got signed to a label in Europe, so we went over for a tour.

For about a year, I was just unemployed with no idea what I was going to do. Photo editing, that whole world was kind of done; the commercial world was really bad―that’s why I got let go from that gig – the money just wasn’t come in. So I went on tour with the band to Europe, and, at that point, I was already making music as Professor Genius. After I got back, I got a job subtitling a TV show. They wanted somebody who could translate and subtitle in Spanish. As it turned out, it was this one reality show I liked―a cop show. I ended up really loving the job, and they were like, ‘would you like to stay here and do something with us?’ So they asked what I wanted to do and I told them I wanted to be an editor, but I’d never been to film school. They told me I could learn everything on the job – and I did.

How did the band come to be?

The band thing happened through mutual friends. They lost their keyboard player and asked me if I wanted to come in and play some gigs they already had set up in New York. It was a very no wave/punk sort of band.

And is film a passion for you, like music?

Anybody who knows me will tell you I’m a film nerd. Technique and a lot of my heroes in film―like the French in the 60s, not only Godard, but also Miéville, the guy who did Le Samouraï―all those guys had their own little studios, their own little setups, their own little teams. It was very DIY. And I associated that with the music scene’s DIY. I’ve always respected and loved artists who do things on their own, who don’t wait for somebody to fork over the money. So, yes, I’m a video editor, but I’m hoping that this year I get some gigs and can play out. I’m focusing now more on my live music than before. I want to play for people―I just don’t get booked that much. I don’t know if it’s because people expect something of me that’s based upon what I did, like, four years ago, with Italians Do It Better and the whole Italo thing or because I’m not a DJ.

Tell me about where you’re from. You’re from New Jersey?

I’m from Paterson, New Jersey. It’s an old industrial city. My folks came here from South America in the 60s. They’re both from Columbia. They were really young when they came here and raised us. My dad worked in the factories, in textiles. So, when I was little, I used to love going to pick up my dad. All the [workers] wore earplugs because the rooms are so loud, but I always loved that sound and the smell of the yarn. Real industrial sound. When I was a teenager, I realized that a lot of my favorite bands―Cabaret Voltaire, bands from Sheffield and Dusseldorf ―were very industrial. A lot of my friends were into punk rock―the Misfits were from Lodi, which is right next-door. Everyone was very working class, blue-collar, and everyone’s parents worked in factories. We all had pretty good educations, but we all came from these backgrounds where there was a lot of noise. I think that kind of gets into your blood.

How did you get into music? Did you play any instruments or…..

I never played an instrument as a kid, but I was always fascinated with synthesizers. I remember listening to the radio a lot―we always had the radio on. If my dad wasn’t listening to his records, the radio was on. So there’d be rock stuff or prog or classic rock, and I was always thinking, ‘What made that sound?’ It wasn’t the guitars. Something came in that was weird. When I was a little older, someone gave me a cassette of [Isao] Tomita and that’s when I saw the synthesizers. You’d pull out the [sleeve] and there was usually a photo of the guy in his studio. So, I think it was Tomita, sitting there with all of his stuff, and I realised what made those noises! From there, it was Prince.

I love watching videos of, say, Klaus Schulze in the 70s.

Yeah―that stuff is beautiful. Nowadays, there’s this fetishization of the machine, the look of the machine. They’re beautiful, and I don’t have as many as some of my friends, like Will Speculator, but I have enough. But there’s such a fetishization of the look when that shouldn’t matter―it’s about the sound. They all have such different sounds, even with the same synthesizer. Someone can have the same one as you, but it’ll sound different; they’re not all equal. There’s a signature tone, but each one has its own uniqueness. I’m not really a purist about that stuff, though―I love digital stuff, too. For some reason, people have this idea that I’ve always been this analogue guy, even though from the first record I put out, it’s been a mix of the two. I didn’t have enough analogue stuff back then to pull it off. When they started making digital versions of those synthesizers that I’d heard on older records, I found they were pretty good, and whatever flaws they had I could cover up through EQing or mixing. I could make the records I loved, but that just didn’t exist. With Italo stuff, I’ve always wanted to make that one record that just didn’t exist, and that’s how Professor Genius came to be.

When did you move away from the band thing and start making music yourself?

I started making music solo in ‘97. I just got tired of waiting on friends of mine who were actual musicians to lend me their four-track or their drum machine so I could just fuck around. I had an income tax refund in ‘97, and I just went out and bought a sequencer and a beat-up 16-channel mixer―who needs a 16-channel mixer, though? A friend of mine lent me a drum machine, which I ended up buying since he never used it. I also got a Yamaha synthesizer and a beat-up little Casio CZ-101―a great little synth but a bitch to program. So, that was my gear, and it was all done to cassette. I taught myself MIDI. I remember calling up Alesis, and asking this guy about why I couldn’t get and sound out of my sequencer. He was super nice and I’ll never forget what he said: Well, no, this is MIDI – there’s no actual sound coming out of the box. I was clueless! The funny thing is that, now, the stuff I made pre-computer time, friends of mine have heard and they’re going crazy about it! Legowelt just did a mix and put two of those tracks on it. I’m thinking, ‘Guys – I have all this other stuff!’ But they find it to be so unique. But, you know what? I’m happy. I’d be up all night, working on these things, and it would all just come out of me.

When was this?

Around 2003. It was before my own solo stuff really started coming out. I played those gigs with the band, but told them I wasn’t really a keyboard player. I came in with a laptop and a controller and told them I wanted to essentially do what Eno did and be another guitar player. I wanted to do noise―screaming, harsh kind of stuff. And when the song didn’t call for that and they wanted a soundscape or ambience, then I could do that. This was with Kid Congo [Powers], who was a pretty well-known guitar player. He was in the Cramps and the Gun Club and some other bands. Anyway, he was totally cool about it, and I ended up being in the band for three years. When we came back from Europe, the band was already kind of on hiatus, and I was already prepared to start getting my stuff out there. Then the magic of MySpace happened, which is how Mike Simonetti found me.

I was going to ask about that―how did you get tapped into that scene? You met Mike through MySpace?

I knew Mike before that. I knew him through people in New York. I’d seen him DJ, shook hands, said what’s up… he’s from Jersey, too. I was making these tracks and putting them up on MySpace, and seeing who was interested. I wasn’t looking for a label or anything, but for other people around the world who did the same thing. There was no plan. But I got an email from Mike saying he wanted to put the tracks out. Italians Do It Better had put out one record before mine, I think, and then After Dark was released, and it was huge. No one expected it to be that big. Pitchfork gave it a great review, and the whole Italo revival thing happened. I really do think that Mike was responsible for that.

Let’s talk a bit about house. One of the things I find to be so cool about the genre is that it’s stood the test of time and can be made by anyone, anywhere today, no matter what its origins. Someone who makes it today wouldn’t necessarily be able to exist in the scene in the 80s, maybe, but they can today.

Which house scene, though? There are so many. And do you think of the idea of genre as restricting? A friend of mine sent me some stuff yesterday; he’s someone who’s pretty well known for not making dance music, and now he’s venturing into that arena. It was really good and he’s clearly trying to make dancefloor tracks, but [the structuring] was a little in and out. So I wrote back and told him I personally loved the track because it’s a house track, but it’s not quite working within the “template” of house music, which means it’s going to be hard to find a label that will pick it up. They’ll say, ‘Can you fix this?’I told him that you might want to think about that if you want to get it signed. For me personally, though, I wouldn’t change a thing. I haven’t heard back from him because they probably want to get the song put out on a label, to get played out, and what I told them is probably not what they want to hear.

I had someone recently listen to some techno stuff I’ve been doing as well as a house track I’ve had sitting around for a bit―they’re starting a label and they said they really wanted to put these on one of their first 12”s, but they wanted changes. I said, No―it’s done. I can give you the stems and someone can remix it and do what you want, make it more “functional,” but I could care less about that. Probably because I’m not a DJ and not concerned with its functionality, and also because it’s done – I’ve moved on. And if you like it so much, why don’t you put it out? Take a risk. See what happens! It is a house track, but it doesn’t fit that “template”, and what’s wrong with that? I mean, I know you have to sell records, but people like Ron [Morelli of L.I.E.S.], he doesn’t care. He’s just cranking them out and his taste is really spot-on, and I’m not just saying that because I’m on his label. Honestly, I kind of wish I wasn’t on the label because [Hassan] has given him such grief. It’s been such an unlucky record.

I heard about the issues with production…

It’s been really frustrating. I’m really proud of the record and he loves it, but I wish he didn’t have to go through all this grief. Having said that, I think his label is really strong, and that’s because he just puts out what he loves. He doesn’t feel like he owes anything to his friends or anybody, he’s trying to challenge what he finds to be too functional and too boring. I wish more labels would be that adventurous. He’s not making that much money, but, I mean, who is? You get gigs. If it’s successful, you make a little cash and your artists might get something, but, ideally, what you do is you get gigs. That’s another bone of contention I have now: if you’re an artist and you’re on a label, you don’t really get gigs. The label heads do. There’s something weird there. That kind of bums me out, but luckily, I love doing this, I love making music.

You’ve brought it up a couple of time so now I have to ask: why aren’t you a DJ?

Because I’d probably be a terrible DJ. I have this real fear of having to go out and buy a lot of records. I mean, I’ve DJ’d around. I played out in Italy a couple years ago, and I was like, Look―I’m going to bring Ableton and I’ll play a set of my influences, and then I’ll play my own stuff over that. People liked it. And I can do a DJ set in Ableton, but nobody wants to see that. Mixing vinyl is really hard for me. I just can’t get my head around it. I’ve tried it and it’s embarrassing, it’s bad.

Jason aka Steve Summers brings a lot of stuff. And that’s really tough for people working within dance music to do. You can’t really “match” the setup that a band affords itself.

You’re right, but I think some of the crappiest live stuff I’ve seen is when you have an electronic producer try to bring his music to the stage with other musicians when the stuff was made with machines. You have a real drummer, a real bassist…. and I wish this guy was up there with an MPC and a couple of synths and a laptop. Like Isolée―I remember when he used to play out, and it was great. He would just use a laptop, but everything sounded very improvised. He was obviously making mistakes and it sounded very organic [despite] coming out of a machine. Something you make with a drum machine isn’t going to sound the same when you play it with [an actual kit]. I love how a lot of people are condensing their setups into suitcases while keeping to their aesthetic. And me, I’m fine with using a laptop. I’ve found a way to use a laptop and a controller, and it’s so great, it’s so liberating.

I guess a lot of people have come to accept the status quo when it comes to performance. A lot of these guys are capable of playing live, but there’s little motivating them to do it. DJ’ing is always either easier or more lucrative. Or both. It’s safe.

I wish more people would do it! You have guys like Marcos [Cabral] and Jacques [Renault] whom I’ve known [traditionally] as DJs, but they’ve gotten really good with their productions. That’s not always the case. A lot of people should just stick to DJing or stick to producing. If there are people who can actually do that, who can actually pull it off, they should do it. So what if you can’t bring all your analogue gear out? Figure out a way to use modules. You can travel with that, and the purest in the audience can be content because. The question is, though: are you going to make people dance? Are you going to open people’s heads up with what you’re playing? Who cares what you use? When Danny [Wolfers, aka Legowelt] was in town recently, he told me that he played a gig somewhere in Europe [with Ableton and controllers], and someone wrote an angry letter to the promoter after the fact. He was upset that he didn’t get to see Legowelt and his gear. Everyone else was dancing and no one else complained so, at the end of the day it’s like, Who cares? Who cares about that one person? I don’t.

I want to ask you about Hassan. Where does the name come from?

I wanted to do a soundtrack to a movie that didn’t exist. I had this idea in my head of a movie about a cult of assassins in the Middle East, in Persia, in the 13th century. I had a conversation with a friend―we were talking about what we would make a fake soundtrack about. I said I’d do one about a cult of assassins. The idea was so exciting that I went home and wrote this thing within a week. I used a certain amount of machines. I wanted it to sound like something from the early 80s, so I put myself into the persona of this Italian guy―totally spur of the moment. So, here’s this Italian guy, writing the soundtrack, and he’s got no budget, but he’s got a bunch of synthesizers, and it’s, like, 1981 or ‘82. I set up a scenario for the movie, a plotline in my head… and I wrote the music. That was just a little game I made up to make it interesting. Hassan[-i Sabbah] is the name of the guy who ran the cult of assassins―he was the leader―so it’s called Hassan. Originally, it was going to come out under my real name, but Ron was like, Well, what do you think about Professor Genius Presents: Hassan? I said, Why not? Although I am trying to do more things under my real name and other ones, like Duermo, for other things I do, for different styles of music. Professor Genius is, ideally, supposed to be the more retro thing, the more Euro stuff.

I really love the album, but it wasn’t necessarily what I expected to hear since it’s not like your other stuff under the Professor Genius name. This is very luscious and epic… and I was actually going to ask if your were at least inspired by movie scores and soundtracks during the writing and production.

Everyone who’s heard it has really liked it, which I’ve very happy with―I think it’s one of the more successful things I’ve done. And I like this idea of working quickly, letting it all just flow out.

Do you normally set up some sort of premise or challenge as you did with Hassan?

I set up parameters sometimes. For example, I’ll say, I want to set up a DMX drum track, and that will give me a certain feel, and I’ll know what instruments go with that. When I first started I’d have a mental image I’d work with. Like, the À Jean Giraud record―that was all based upon some drawings of Moebius’ I’d seen, and that got some music in my head… very French, very 70s… like Vangelis or something. When I do the dance stuff, I think of the floor of a room that I know. It can be a peak-hour sort of thing or a little subMercer sort of dark basement space with a fog machine, and I’ll make a track for that room. And then, a lot of times, I’ll play a sound and things will come out of that; it evokes things, things that I love, that I’ve heard. Writing the techno stuff that I’ve been working on, it’s been fun―it’s very Detroit with lots of lush chords.

It’s not released, right?

Yeah, it’s not released, but I’m going to be playing a lot of these things out live. I’ll be playing a lot of house-y things out live, too. I’ve got so much stuff together, I’m just holding off on releasing it until Hassan comes out.

You started your own label too…

I tried to bypass the whole distributor system with a short-lived 7” label. Like, buy them from me cheap, I’ll send them to you. But I’m still sitting on 150 of them! It’s a great little 45 that was mastered beautifully. The artwork’s beautiful, the tracks are each around 3:45 each. But it went nowhere because people don’t want to buy 7”s. That was my attempt at starting a label. I just didn’t want to do it the standard way because so many people are already doing it, and doing it well.

Not many people do that these days. Like, Ron and Mat Werth from Rvng Intl. are standouts because they do everything on their own.

Will Speculator, too.

Yeah. They’re in the minority. But it’s tough to turn down a good production and distribution deal. If you do it on your own, though, you’re so deeply invested in the artistic, creative, and financial elements that your standard of quality is maybe a bit higher. Or, rather, you pay more attention to every detail of the business.

Veronica [Vasicka] is the same way with Minimal Wave. She does everything herself.

By that same token, some people like, say, Marcos with Hamilton Dance Records, jump on the opportunity because they can release incredible music without having to worry about the nitty-gritty elements quite as much. There’re too many people out there who’re getting away with the luxury of having some other company foot the bill for their releases.

I remember people asking me, Well, who’s your distributor? The whole point was that it was all supposed to be handled by me, but they were like, No, no, no―we can’t do that. But it sold great here, at Other Music and Turntable Lab. I’d bring in copies and they’d fly off the shelf. I’m sure if I tried to get rid of the other 150 it wouldn’t be too hard, but I’m over it. I move on to the next thing! My whole thing is to just keep making music. There are so many great people here in New York, and I’m just so happy to be a part of it. I’m really looking forward to doing some stuff with friends.

Actually, one that note, I was going to ask: what’s the Bim Marx thing? Isn’t that the only collaborative thing you’ve done?

It’s with Duane Harriott. No, I also did the PG&S thing with Will Burnett, [aka. Speculator]. I’m a little bit of a control freak, so I kind of like to do everything on my own. [Laughs] But, yeah, Bim Marx, Duane and I are old friends. Those are edits, and that project is sort of on the backburner now. Those things were super popular, though. Duane and I did a bunch of remixes for people, but they kind of went nowhere―they just became, like, digital-only things. We did a really kick-ass remix for DFA. DFA loved it, but the band hated it, and it went nowhere. I think the next project that we’re going to do together is a mix CD. We just do a bunch of weird edits and interludes and make it trippy. The first one we did went really well. Me, personally, I’m kind of over the edits thing―they’re becoming the mashups of [the 2010s]. Everybody makes an edit now, and people are really good at making them, so what’s the point? I like the process of making them, but I don’t really care much about the end result. With Duane and I, we just love the process―we laugh a lot and have a great time, and, luckily, the label likes them and people love playing them out. But the mix CD, that’ll be really something that I can get into.

You put those out yourselves?

Yeah, we make CD-Rs, almost like a hip-hop mixtape. I’m actually thinking about doing a CD-R of my own stuff, too. Really cheap with a bootleg stamp, like the first CD I ever did, which was a CD-R. Get it mastered nicely, but bypass the whole expensive CD production thing, [with minimum orders] of 1,000 or whatever. I don’t want 1,000! I just need 300. Get them out there, mail them out, and when it’s gone, it’s gone. Maybe a year later, I’ll put it out there digitally. I think that’s a good way for me to get my music out and still give people a little object. It’s kind of ghetto, but I like that―it’s still kind of punk. If I do the CD-R, I’m going to get Dan [Selzer] to do the covers for them since [he’s opening a letterpress shop]. I’ll sell them for $10 a pop. The first CD I put out was a CD-R and I went to some place in midtown that did all the hip-hop CDs. It was the most gangster operation; these guys were all such ballers. That came out right around the After Dark compilation, which was good since people would get that and then [my record].

Finally, have you ever done professional illustration work?

No, but I’ve been drawing since I was a kid. I did the artwork for the À Jean Giraud record. I’ve never had the opportunity to draw my own label for a record, though. But when I was younger, in the late-80s, I was really involved in the mail-art scene. People would xerox comics and send them to people across the country, across the world. Gary Panter was involved in that, and I was a huge fan. I used to do my own comics, too. When I was a kid, I wanted to be a comic artist.

Interview: Nik Mercer

Main pic: Damien Napoli