Dutch Masters: The New Sound of Holland

Holland doesn’t have the same status as Detroit or Chicago or boast the kind of game-changing clubs that New York and Berlin have been home to, but its importance in electronic music spheres cannot be understated.

Despite Holland being a small country, since the early 90s the creativity and freethinking approach that Dutch artists embraced have ensured that it punches way above its weight.

The outside world first came to know about Dutch techno and house during the early to mid-90s thanks to groundbreaking releases by Speedy J, Gerd, Like A Tim, Steve Rachmad, Erik ‘Shiver/Essit Muzique’ Van Den Broek and Stefan ‘Terrace/Florence’ Robbers and labels like 100% Pure, Eevo Lute, Djax-Up Beats and Outland – which provided platforms for local and international talent.

Around the same time, that other less palatable Dutch musical style, gabba, was exploding, introducing a violent, testosterone-fuelled undercurrent to hardcore dance music. ‘Gabber’ translates from Dutch as ‘pal’ or ‘mate’ and was used as a term of endearment by the amphetamine-riddled skinheads who populated these events.

While gabba endured, Holland’s second wave of techno and house also emerged during the late 90s and early noughties. Spearheaded by Amsterdam’s Delsin label, it provided a home for Newworldaquarium’s spacey house, Aroy Dee’s deep techno and Aardvarck’s abstract beats. It was also during this period that I-F put out Space Invaders are Smoking Grass, a release that inadvertently served as a catalyst for the rise of electroclash.

While I-F had been making visceral techno since the early 90s as Unit Moebius and came from the same acid-soaked squat scene as the long-running Bunker label, the Space Invaders single and timeless Mixed Up In The Hague DJ mixes put the spotlight firmly on the Hague and Holland’s West Coast electro-Italo-jack sound that includes Legowelt, Alden Tyrell, Dexter and Orgue Electronique as well as labels like Viewlexx, Creme and of course Clone.

Fast forward a decade and Clone, along with Amsterdam’s Rush Hour, operate as global hubs for US house and techno focused-music through their three-pronged label-shop-distribution approach. Meanwhile, 2562 and Martyn have offered unique perspectives on bass music. In parallel, the past few years have seen two new Dutch producers, Delta Funktionen (aka Niels Luinenberg) and Conforce (aka Boris Bunnik) revisit the techno sound that originally put Holland on the international map.

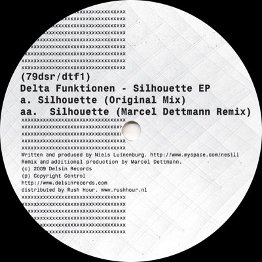

The methodology applied by this new wave of producers echoes the approach of pretty much every other innovative Dutch artist before them; take an existing form and add a unique, signature touch. In the same way that Steve Rachmad rewired Detroit techno with his benchmark Secret Life of Machines album or Legowelt stamped his identity over Chicago jack and tripped out Italo, Luinenberg’s debut, Electromagnetic Radiation brought with it a particularly ponderous edge to dub techno. By contrast, the follow-up, Silhouette, on Delsin sub-label Ann Aimee, out-menaced anything that the Berghain residents could muster, as a growling bassline merged with grimy loops.

Bunnik brings a more esoteric approach to bear on his productions, from his electro project Versalife to the widescreen at times ambient techno of his latest album, Escapism, as Conforce for Delsin. But despite growing up amid such rich musical surroundings, neither Luinenberg nor Bunnik was immersed in cutting-edge techno as kids.

“I grew up in the most northern part of The Netherlands. It’s pretty isolated from the west coast and so there were no clubs or record shops,” Niels explains. “My parents weren’t that much into quality music either, so I had to discover it on my own. Luckily, the radio and TV offered dance-related shows from time to time. These were mainly focused on cheesy and easy to consume dance music, but were still eye opening.”

For Luinenberg, true inspiration came from an unexpected source. “The local library was basically my main source for finding music. You could rent a CD, mostly compilations, and copy the stuff you liked and create your own mixes. I probably spent more money on CDs than on books! Later on there were some big stadium raves in my hometown. The father of a friend worked at the local fire department and he allowed us to sneak in to one of them, so at the age of 15 I visited my first rave. It was a mix of club music and some trance, pretty poor but still a great introduction to a world I had only heard about,” he recalls.

“The next year there was another rave and I was the legal age (16) to visit it. The music didn’t attract me that much, but there was a talent room where a guy dropped some techno, kind of groovy Drumcode stuff. I was immediately hooked and didn’t leave the room until the end. I was deeply touched by the rhythmic parts and the indefinable sounds. The next party was one month later in a city nearby. I stayed in the techno room all night where James Ruskin was killing it. I got completely hooked on the sound, but my friends couldn’t really get into it. This was the start of a long time of solo travelling through the country. At times my parents were a bit worried about me visiting parties across the country, but my need to discover this world was way too strong to let them stop me.”

When Luinenberg turned 20, he started to attend university at Leeuwarden. “There was a small techno scene,” he says. “Through Damian Keane from the Audiosculpture label I discovered a lot of more underground techno, mainly UK stuff, but also some American productions. We became good friends and started to work on projects. Through Damian I got to know Dave Miller and they became my mentors. I learned a lot from them regarding production, but also DJing, how to build sets and getting to know the techno weapons.

“Later on I started working at Deeptrax Records in Leeuwarden,” Niels continues. “We mainly sold second-hand records. A lot of Detroit and Chicago stuff, alongside the better European techno. When we received a collection to sell, I was always the first to go through this collection before we put anything up for sale. In this way I discovered a lot of gems and basically spent all my hard-earned money on records. So it has been a long journey of discovering music and I’m happy that it went this way.”

Bunnik meanwhile was also quite young when the first wave of Dutch techno appeared and he admits that it was only later that producers like Rachmad and Speedy J influenced him. “The first selection of techno tunes I used to learn and beat match with included tracks from Sterac, Gerd etc,” Boris says, adding that the other musical sound sweeping through Holland at the time also had an effect on him. “I was also listening to a lot of Dutch hardcore and gabba. It was really huge at that time and also inspired me. Gabba/hardcore was pretty much the only musical sub culture ever to rise from the Netherlands. Influence is a big word but for sure it did something with me apart from irritating my parents with the kick drums!”

But Bunnik was also developing a taste for deeper techno and says that Rachmad’s side projects as Parallel 9 and Ignacio “really grabbed my attention. I think it’s Rachmad at his best. One cool record I can remember from Gerd was Arkest’s Blaze; I used it to learn beat matching. Timeless Altitude by Secret Cinema is of course a recognisable classic that got played a lot at the local disco on the island I’m from. I don’t particularly like Speedy J’s harder stuff but I enjoy his more ambient/IDM orientated tracks. Ginger is a great example of that, it’s a truly influential record for me but I discovered it pretty late.”

Despite developing an affinity for the deeper end of Dutch techno, Boris admits that some local producers went over his head. “Terrace is one of the Dutch artists I didn’t listen to, but I once had an Ableton workshop from him at my school,” he explains. “I never really got into his music but I do respect what he achieved by doing his own thing and creating his own interpretation. I know he has been a very progressive artist and a big inspiration to a lot of artists. I should get into his older stuff.”

Bunnik is loath to admit that a particular producer has influenced his work and he sees music making as the by-product of a set of subliminal factors. “Of course I’m influenced by everything, but in a very sub-conscious way to be honest. I think it would work the same for everyone or you have to lock yourself into a bunker and remain isolated, which is impossible. We are all being triggered by something, also when people meet people and they hang out with each other. I take influences from everything and sub-consciously blend it. I’m not sitting in my studio thinking about copying the Detroit or Rachmadian blueprints. Moods trigger sounds and sounds trigger moods. For me it was mainly European house and techno that triggered something in me, also some great early UK stuff from Slater.

“I discovered Detroit techno in a later stage,” he adds, “and in recent years the Ann Aimee and Delsin labels have released a lot of great techno. Delsin has been doing this for over 10 years, but it seems like they have put out a lot of great material lately.”

Bunnik and Luinenberg are both still in their 20s, but have mature heads on young shoulders. Niels started to produce when he was in his mid-teens and recalls that when he started “it was mainly about losing myself in sounds, but nothing serious came out of it. Later on when I met Damian and Dave, it all became more serious, regarding techniques and the vision behind it.”

Niels was more interested in production, almost by default, because he couldn’t afford to buy turntables. Inevitably though, his releases led to DJ requests. “By 2006 I had been buying records for a year or so and needed to learn the basics of mixing. As the requests kept on coming, it was time to take DJing more seriously and it has now grown into something I earn my living with.”

But let’s return to the question about the effect of the immediate environment on Conforce and Delta Funktionen’s music. Given that Dutch society has a liberal attitude towards sex and drugs – although the country’s Calvinist roots mean this perception is not accurate outside of urban centres – do they feel that this creates an atmosphere that is conducive to making music and being creative?

“It’s definitely not 100 per cent accurate,” Niels laughs. “It’s a tough one, because I think that most great, original music comes from situations where life conditions aren’t that great. The perfect examples are of course Detroit and Berlin. But that’s about the past; for the present I can say I have a tremendous drive to make music and translate my ideas into sounds. I don’t need a system or government making things worse, or easy, to create something. I just listen to my own feelings and create something from that. The whole techno scene has always been a DIY thing. Even now, when the Dutch government cuts a lot of arts-related funds, I don’t feel like I shouldn’t be doing this. However, I understand that it’s definitely not easy to make a living from an underground hobby.

“High rents make it almost impossible to focus only on underground music or art, but this is the same all over the planet, except maybe for Berlin. I’d rather have all these struggles in life compared to spending my time in an office. I tried that but failed completely! In the end I’m happy that I’m now able to do what I want to do and make a living out of it,” Niels adds.

Boris agrees that Holland’s famed tolerance for the arts and alternative culture is nearing an end and claims that the government is “tearing apart the creative sector”. However, he sees this as a positive development and expects a positive reaction to a curtailment of state support. “Some people tend to lean too much on government funding – I think it’s good for new initiatives to be independent,” he believes, adding that it’s “really great to hear you talking that positively about Dutch techno in general, but I can only speak from my own point of view, from the environment I’m from. It’s down to earth, there’s no scene, there’s no clubbing life, it’s very authentic and conservative in a lot of ways and not artificial. It lacks a lot of things especially when it comes to the cultural perspective. But what can you expect from such a small place in general. For me it works really good, I’m not distracted I can focus on what I wanna do – make music.”

But despite these claims, there is no doubt that both Conforce and Delta Funktionen’s ability to twist new shapes out of existing narratives means that they are following in a tradition that started in Holland in the late 80s. Can they offer any insights as to why Dutch producers, DJs and clubbers so readily accepted house and techno?

“I wasn’t there when this whole movement started, so I can’t tell the reasons why. I can only guess that some underground radio stations might have played a big role, and what the shops offered by the time,” Niels says. “There was quite an active party scene around the west coast, and from the start the big guys from Detroit were playing there. This probably influenced a lot of people and so they might have started working within this tradition.”

One of the other possible reasons why Holland was such an early adopter to electronic music is due to its past. A small, sea-faring nation with colonial ambitions, it has traded with the rest of the world for centuries. This meant that Holland was always open to outside influences. Niels agrees, but feels that a collective desire to create a counter-culture also helps to explain the appetite for underground electronic music.

“I also think it’s the fact that public radio and television always offered mainstream music and that there’s hardly any space for more interesting music. This might create an atmosphere where producers and DJs want to diverge from that image, and grab their own influences and create something out of it,” Niels believes.

“At least it worked for me in that way. If I speak to people from other countries, I’m always surprised by what kind of music they grew up. A lot of electronic music was spread by radio and television, so their influences are much wider. I simply had to discover everything by myself, and I’m still discovering a lot of great musical ideas which I try to apply into my own music, in my own way.”

Back to the present day, and to an outsider, it appears that Holland’s electronic music scene is in great health – the Clone and Rush Hour distro/label/shop hubs provide the infrastructure for their in-house imprints as well as for labels like Delsin, MOS Recordings, Ann Aimee, Moustache Techno, Crème / Crème Jak and electro operations like the evergreen Bunker, Murder Capital and Frustrated Funk. Luinenberg agrees that on an international level, Dutch labels punch above their weight.

“There’s a lot of great music coming out on these labels. One could say it’s sometimes a bit too much rooted in old school stuff, but I don’t care that much about it. I like old school drums and love to play them out. If the idea is right, the feeling is good and the track blows me away, I’ll play it. The guys in Rotterdam, Amsterdam and The Hague know each other, but I’m from a different part of Holland and never had the ambition to be part of something.

“The scene in Holland is still small,” Niels believes. The promoters still book a lot of minimal stuff, so there’s no active party scene regarding music and artists coming out on these labels. In that way we’re definitely lagging behind Germany and the UK, but also a lot of other European countries where promoters take more risks and where crowds seem to be more open to these sounds. Of course there are some parties and events happening in Holland, but it’s not as widespread as in other countries. It all moves really slowly, which is sometimes frustrating to see, but I’ve accepted it. It’s not something new, it’s been like that since I went out clubbing the first time.”

Bunnik also feels that his music has niche appeal and no matter what the outside perception of the Dutch electronic music scene is, Conforce remains an underground project in Holland. “There are a few niche labels I can really identify with and I stick to them,” Boris adds. “I think Delsin for example is more respected outside the Netherlands. Sometimes I tell Dutch music lovers/clubbers that I release music on Delsin or Clone and they are like “what, never heard of that label?” We’re all in a niche and I think it has to do with the DIY mentality that they are still standing. They truly do what they believe in, and it serves as a good lesson for others.”

Ironically, it was the music that Luinenberg made while he was still living in Holland that lead him to leave the country last year. However, he asserts that his move to Berlin was more down to a question of simple logistics than a failure to survive as an electronic music producer in Holland. “In Holland I lived too far away from the airport, and as the foreign requests kept on coming, I simply had to move. I was getting used to spending one day a week extra for travelling. This was killing me and I always had to ask friends to stay and sleep at their places in Amsterdam before heading towards the airport. You can do that for one year, but at a certain point you have to realise that when it becomes a profession you should act like that and make your transition. I had to choose between Amsterdam and Berlin and picked the latter,” he explains.

The demand for Luinenberg’s DJ skills was a result of a combination number of factors: the strength of the Delta Funktionen releases and a renewed appetite for purist techno. The fact that a number of his DJ sets had been posted online – in true Dutch fashion he was engaging with the outside world – was also crucial. “When I started DJing, I mainly had gigs outside Holland. I think this had more to do with my first releases,” he says. “They came out at the same time as this whole Berghain thing happened, so I was lucky to be part of that wave in a way. Suddenly there was a focus on more pure techno instead of fancy cheap minimal stuff. Later on I got more gigs in Holland and I assume that my warm-up set for Jeff Mills helped me to get more gigs. I still get a lot of compliments about that everywhere I go, which is really great! I didn’t do any promotion last year, except for one podcast, which showcased tracks I played out a lot during the last year.”

However, Luinenberg is at pains to point out that his DJing style varies wildly, from the deep opening set for Jeff Mills – “the people in the club bought a ticket for him, not for me. So my job was to get the people into the right setting so Mills could take over and kill the room” – to the upfront approach that he delivers on his new mix CD, Inertia, for Ann Aimee.

It’s the same on record – the main strength of the Delta Funktionen project is its range, from the deep and dubby Electromagnetic Radiation to the lean menace of Silhouette into jacking, metallic techno on the Set Up series. Niels also does the Phantom Regiment project with Damian Keane, which focuses on harder techno.

“Diversity is the key for me, probably because of how I got into this music and the long search it took to get there,” he feels. “I have a lot of influences and I try to put these into my own music, whether it’s dubby or more banging stuff. I simply don’t see myself making dubby chord techno all my life. That would be too boring, the same as making only banging club techno. For that reason I like to work in small concepts.

“The Electromagnetic Radiation series was focused on deeper, ambient sounds. The Setup series came out when I was DJing a lot and felt like I wanted to make some more banging original club tracks which were a bit more peak-time, but still with a concept behind it. The clue to the concept of the Setup series lies in the engraving of the last Setup. When putting these words in between the track titles, the concept will be clear,” he adds cryptically.

Niels’s relationship with Delsin originated through Deeptrax, the record store he worked in while at college. The owner knew Marsel from Delsin. Niels emailed him some tracks and “within three days we had an agreement”. “Marsel was thinking about re-starting the Ann Aimee label and thought these tracks fitted into it. Since then we’ve worked together and everything feels totally fine,” he explains. Niels has released almost exclusively on Ann Aimee or Delsin, which was a conscious decision. “I don’t see the point of releasing on many labels,” he says. “I prefer to work with a few people I can trust and with whom I can build a relationship, rather than just dropping a record every two months on a different label.”

Luinenberg’s relationship moved up a few levels with the recent release of the Inertia: Resisting Routine mix CD. Consisting entirely of unreleased tracks by well-known names like Redshape and Peter Van Hoesen, breakthrough artists like Cosmin TRG, Sigha and Lucy as well as producers embarking on their first tentative steps into releasing music – Area Forty_One, Sawlin and Marcelus – it was the culmination of a year’s collaborative work between the label and Luinenberg.

“Marsel had the idea sometime in late 2010,” recounts Niels. “He wanted me to be involved in the A&R process and finally do a mix CD. Later on, Maarten, who was working as an intern at Delsin, got involved with the process and the three of us did the A&R. We had a list of producers we wanted to be part of this project, but some cancelled or weren’t able to deliver a track on time, so we had to find some other artists, which made it a longer run than expected. But now it’s done and I’m very happy with the final results. It’s a nice balance between more established producers and some relative newcomers and a good overview of where more modern techno has headed,” he believes.

It also portrayed a different, albeit harder approach to DJing than Niels’ online sets had previously hinted at but something his Set Up productions showed him to be capable of. For anyone who has heard the mixes hosted on the mnml ssgs blog – both the three-hour warm-up for Mills and the specially commissioned selection for the website – Inertia will probably be something of a rude awakening.

“Yes, people might be surprised when I play that kind of stuff. But rather than fulfilling any expectations I prefer to deliver in a way no one expects and get people talking,” he claims. The next project that Niels will deliver is his debut artist album for Delsin: “It will cover tracks I made during the years, which didn’t fit into the other concepts, but from what I feel they should be released. So it will be pretty diverse and different from the other music I’ve been releasing till now.”

In the meantime, the label has just released an album by Delta Funktionen’s peer Conforce. Like the preceding single, Dystopian Elements, Escapism combines swirling synths and moody soundscapes with grainy drums and rasping percussive licks. Like 2010’s Grace EP, the album also includes dreamy ambience, but manages to retain the bass-led menace audible on last year’s superlative State Of Mind on Clone’s Bassment Series label. In places, Escapism is reminiscent of Carl Craig’s Landcruising album, in other instances it boasts the brittle melodic flourishes of vintage Sterac and the grainy bass of Drexciya. Is this mixture of darkness and light intentional?

“I love subtleties and I love subtle grooves. Some tracks are more detailed than others, but it’s all about subtleties; that’s where I can really express something. Sure some tracks are pumping but I hope the subtleties remain. I think the Detroit thing is more of an overall feeling instead of a real solid definition. The dreamy atmospheres are a reflection of moods. If I do my best to create a banging track I usually end up with something more restrained,” he explains.

Yet the Detroit connection remains, in the same way that it loomed large over Steve Rachmad and Stefan Robbers’s greatest releases during the 90s. Apart from the interplay between the album’s dreaminess and its unexpected dalliances into darker techno-bass, the title itself suggests that, like the first wave of Detroit techno and electro producers, Conforce is using his music as a means to get away from the concerns of the real world. Does Bunnik use his craft to detach himself from everyday life?

“For me, electronic music is mainly an escape from the moment. I think some producers recognise the moment where you are completely in your own zone, disconnected from every peace of reality. I like to create my own worlds, most of the time. Sometimes grimy, sometimes very peaceful,” he says, before tempering his comments. “I’m not saying the world is a dark place right now, but there’s some serious stuff going on. People are certainly quickly estranged from themselves these days and a lot of stuff is artificial – but I keep looking at the bright side!”

Despite the melancholic side to his music – and Escapism is full of such moments – Bunnik is generally upbeat about the state of electronic music from Holland. He agrees that there has been a “techno resurrection going on over the last years in general and it’s good thing. There are so many good small labels and new artists making new interpretations in this genre. It’s amazing, last year was stunning. Great music got released, it’s even hard to follow it all”. Bunnik immersed himself in the recording process for the album, but his input didn’t stop at the recording studio door. Delsin gave him complete creative control, which meant that he oversaw the artwork. The album cover features a Japanese project manager wearing a hard hat as he looks down at a cityscape below him – and is Bunnik feels, linked closely to the music.

“The photography was done in Japan in 2010 and just kept inspiring me. There was a strong connection with the music and the theme that was on my mind whilst making it. In Japan I was inspired to combine the pictures with music and the vinyl cover and artwork are a metaphor for the title,” he explains. “For me it makes sense but I don’t know how others look at it. As long as we are happy with the result it’s good.” Bunnik is heavily involved in design and photography and sees a strong link between visual and musical expressions, believing that they come from the same creative thought process.

“I like to connect the visual and the audio aspect with each other. You miss an opportunity when you don’t connect these two. Music speaks to the imagination so does a piece of art,” he says. The flipside however, is that a bad piece of art can let down the accompanying music – and vice-versa. “When the artwork is crappy you will relate it to the music although you haven’t heard it yet. Finding the right balance between both is essential,” he feels. “An image is a thousand words; it can hit certain emotions and trigger the power of imagination. I try to capture an image but also try to put it in a new context, shape a different atmosphere. Capture a piece of reality but get it out of its original context.”

If his artwork captures part of Bunnik’s reality, then his work as Versalife represents another side. Boris admits that the project is “just a play garden for my own imagination and if I can transfer that to other people by making the music it’s great”, but such a description is a disservice to the sublime, esoteric electro that Versalife has yielded.

The forthcoming Night Time Activities by Versalife on Clone is one of 2012’s finest records – when this writer first heard it, I had to check to make sure I wasn’t listening to a long-lost Stinson or Donald side project – yet Bunnik is self-effacing.

“The whole project started for fun and was inspired by a fictional corporation from a virtual reality game plus an analogue drum machine. I keep that dystopian artificial atmosphere in the back of my mind whilst creating tracks,” he explains. Bunnik’s creativity doesn’t end there and he also plans to tease out the ambient sounds he flirted with on Grace and Escapism. “I finished an entire new Hexagon project that will hopefully see the light of day. It will be more experimental and beat orientated but still with a lot of ambient atmospheres. Sometimes it’s more interesting than techno,” he believes. “There’s space for different emotions and ideas.”

Listening to this new wave of Dutch masters, it’s clear that anything is possible.

Richard Brophy

Top image: Conforce (left), Delta Funktionen (right)