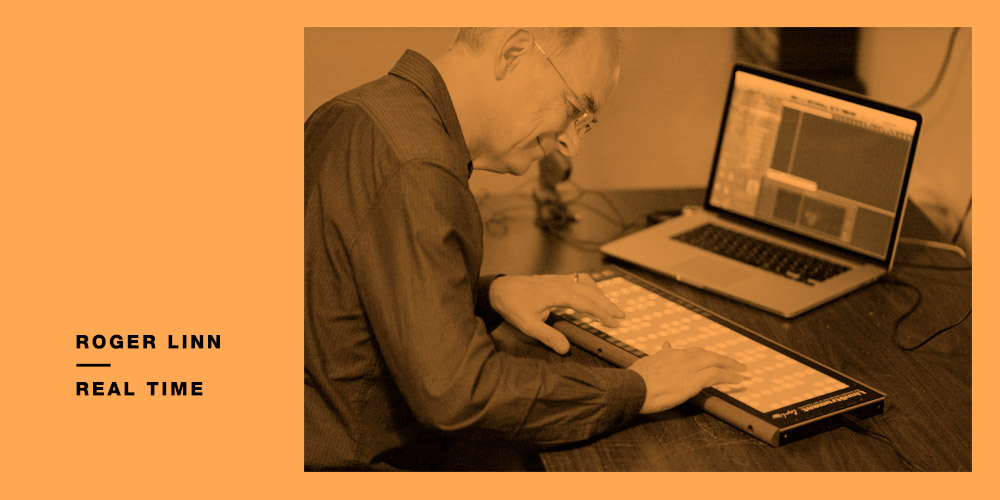

Real Time: An interview with Roger Linn

Revolution, on/off switches, Prince, Fleetwood Mac and Stevie Wonder just some of the topics influential instrument designer Roger Linn discusses with James Manning.

Five years ago when Roger Linn was awarded a Lifetime Technical Achievement Grammy for his services to instrument design, his acceptance speech touched on two things; an impending high tech revolution and his mission to save the musical note from extinction. So can we, in 2016, verify that a revolution has taken place, and do traditional hallmarks of song writing like chords and instrumental solos mean anything to music today?

Roger Linn suggests we are at something of a tipping point, and he should know. From the late-‘70s through to the early-‘80s he was a foremost pioneer in developing sample-based drum machines alongside Roland. His LM-1, LinnDrum and MPC60 and MPC3000 models are regarded as instrumental in revolutionising mainstream pop music, hip hop all the way down to leftfield bedroom experimentation. Prince essentially commandeered the LinnDrum as his own while the likes of Herbie Hancock, Michael Jackson, The Human League and countless other synth pop greats maintain LinnDrum’s historical infamy.

Furthermore, Linn’s designs have invented things like quantisation, swing and loop recording – all of which are now standard features in any digital work station. These days, however, Linn is more focused on what he simplifies as a man-machine interface; LinnStrument. The new controller is designed to give players learned in scale and expression the ability to work with sound in a simultaneous, three dimensional way; taking into account things like pitch, amplitude, vibrato, slide and more. It’s something Linn says will give performers the ability to play with something outside of on/off switches, aka: MIDI keyboards.

In his quest to resuscitate the instrumental solo from today’s musical arrangements, the American met with James Manning for a much needed coffee in Camden following a red-eye flight direct from San Francisco. In the interview below, Linn elaborates on his time rubbing shoulders with LA’s rich and famous, demoing early machines at Stevie Wonder’s place to Fleetwood Mac parties, while further explaining his time as a Leon Russell protégé amidst calling the traditional keyboard set up archaic and out of date.

So you’re a mandolin player, specialising in the ‘classic round back’?

Yes, they are called ‘Potato Bugs’.

So you moved on to the mandolin from guitar?

When I first moved to San Francisco I would sometimes hang out in the mornings at a place I liked in the old North Beach Italian section called Caffe Trieste. It was first Italian cafe there, founded in 1957, and is dripping with local culture and conversation. Once I was speaking with one of the guys in the instrumental band that played there on Saturday mornings and he asked if I’d like to sit in on guitar, which I did and continued to do so over the subsequent months. After a while the 80-year-old mandolin player became ill and eventually died, so they needed someone to play the mandolin. I picked up a mandolin and learned some of the Neapolitan melodies and ended up playing there for 15 years, with the instrumental band morphing into an Italian opera ensemble called Trovatore.

Are you still part of the group, Trovatore?

Are you still part of the group, Trovatore?

I stopped doing it about a year ago because it got a little boring. I wasn’t learning any new material and I was getting very busy with LinnStrument.

So that’s it for the gigging life at the moment?

That’s true. At this point it takes so much time, but my musical satisfaction is served mostly by recording videos for LinnStrument, and to be honest I don’t play guitar or mandolin anymore, I just play LinnStrument. It’s more fun for me to play.

I’ve watched your tutorial videos about LinnStrument.

Unlike the on/off switches of a MIDI keyboard, the purpose of LinnStrument is to permit expressive performance of electronic sound, which it does by capturing all three dimensions of your finger movement for continuous control of each note’s loudness, pitch and timbre. One of the questions this raises is: given that the vast majority of electronic musicians seem satisfied playing on/off switches, is expression even important? To answer this I went to Billboard’s top 100 chart, which is a weighted average of sales, downloads, streams and radio play, intended to suggest what people like to listen to. Of the top 20 songs there, 18 of them were electronically generated except for the singer’s voice. The same 18 had no instrumental solo, suggesting that the whole concept of an instrumental solo has virtually disappeared from electronically-generated pop music. By comparison, there has usually been an instrumental solo in earlier musical genres like rock, pop, jazz, country, etc. So the question is: why do the listeners of electronically-generated pop music not care about instrumental solos?

Does this mean that musical expression is no longer valued? Apparently not, because the singers have wonderful expression, which I define as containing lots of skilled variations in loudness, pitch and timbre over the duration of each note or phrase. If people do value expression, is the problem that there are no good musicians? I don’t think so. My theory is that in electronically generated music, the solos are not interesting because they are played on on/off switches, which is essentially what a MIDI keyboard is, and that is what LinnStrument and a handful of other new expressive electronic instruments are trying to change. After all, on/off switches were designed for secretarial data entry, not for music.

So you’re still on the campaign to stop the musical note from extinction?

I am. The LinnStrument is my salvo.

Congratulations on your Grammy. I watched your acceptance speech where you suggested that a high-tech revolution is coming. That was 2011, it’s 2016 now, is the LinnStrument part of that revolution?

There are actually five polyphonically expressive electronic instruments. The first one was the Continuum, released back in 1999 and is still popular. And then came Eigenharp, an English instrument that had some very good ideas. Then there was the SoundPlane and next the Roli Seaboard, a beautiful and very functional design. And I came along last with the LinnStrument. We’re all good friends and on the same mission – to rid the musical world of on/off switches. I think people are starting to talk about expressive controllers and the limitations of playing music with on/off switches. I would say it’s a revolution about to happen.

When you were designing drum machines back in the ’70s and ’80s, how futuristic did it feel to be making that kind of instrument, then?

I’d say with every product I’ve ever done, acceptance has followed in what’s called an inverted bell curve. It starts with high demand from the visionary early adopters, then there’s a lull, then once the word starts to spread and people see the lasting value, the demand gradually picks up and continues to grow and grow. My drum machines were like that at first, they were red hot out of the gate, then slowed down a little and then picked up big time. At first people were wowed by pressing a button and hearing a recording of a drum, because sampling was as yet unheard of. But it took a while for people to also appreciate their real-time musical operation, including how easy it was to record beats in a loop with the new ideas of timing quantisation and swing. Thirty five years later, it’s an essential part of many forms of music.

I think it’s the same with LinnStrument right now. People are gradually developing performance skills on their LinnStruments and the word is spreading. There are still a lot of experimenters, noodlers, techy-type musicians. I suspect that many musicians with high acoustic instrument skills aren’t yet embracing LinnStrument, perhaps because their life commitment to their chosen acoustic instrument prevents them from seeing the value in this new-fangled contraption. But it’s happening, slowly but surely.

So when you spend all this time researching and developing something like the LinnStrument and early LinnDrum models, would you see people using the instrument in ways that you didn’t predict when you were making it – is that a recurring theme with instrument design?

It is, certainly. A great example being when I made my first drum machines that were able to sample your own sounds, I intended this only for drum sounds and didn’t offer much memory. I was completely blindsided by the idea of people wanting to use them to sample entire sections of recordings – loops—and use these as elements in a song. As I like to put it, I make the brush and the artists choose what to paint with it. Sometimes I’m pretty close at predicting that and sometimes I’m way off.

So would say you work in the realm of digital even though people assume it’s analogue circuitry because of your history with drum machines?

Yes, until my recent Tempest drum machine I had never made an analogue product, only digital. Yes, I think I’m often associated with analogue synths because my contemporaries are people like Dave Smith and Tom Oberheim, who made analogue machines. And even in Tempest, Dave Smith handled the analogue part of that. All my other products have been digital, and my first drum machine in 1980 was the first sampled-sound drum machine.

What has it been like watching digital come of age?

The only thing I miss is that early analogue synthizers by Dave Smith, Tom Oberheim or Bob Moog command a very high resale price, while vintage digital isn’t quite the same because an old bit sounds the same as a new bit.

How was that period when Roland released the 808 and 909 drum machines?

It was very exciting to watch how drum machines bifurcated into two camps. There was the 808 camp, embraced by step-time programmers, and then there was the LinnDrum or MPC type camp that were primarily real-time players. I think the people who used my machines had better performance skills, so step-time was too slow and limited for them. When you’re programming step-time you have to deconstruct everything in your mind into a mathematic assembly process. If you’re programming in real-time you simply play the musical parts and dynamics that you hear in your head, but you have to know how to play in real-time. People who preferred the 808 step-programming approach often didn’t quite have the real-time performance skills so it helped them to assemble the drumbeat piece by piece.

Both methods worked and both methods produced beautiful musical ideas, but with step-programming, you always end up with something very mechanical. You couldn’t get a completely natural sounding beat out of the 808 if your life depended on it because you only get two dynamic levels and you always have this very obvious synthesised sound. But in the ’80s, the style was often to make it sound as robotic as possible.

When my first sampled-sound drum machines came out, many people initially thought they would replace the analogue products. But I admire Roland and its founder, Ikutaro Kakahashi, for sticking with the 808 approach, though they also made some very good sampled-sound drum machines. Eventually the 808 and its successors became very well-loved, and the idea of 16 buttons for step time programming – even with only two dynamic levels – inspired a lot of great music.

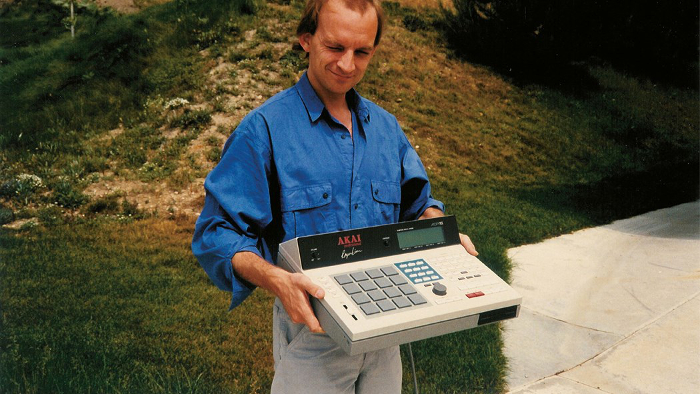

So the MPC60 was upgraded to the MPC3000. How much work, research and feedback goes into the upgrading process?

Nearly all the work went into the MPC60 and the MPC3000 was essentially just faster, more bits, more memory, more everything. The good thing was that Akai pretty much let me do what I wanted with the design, which was very nice.

And you worked with Alan Trimble on that machine?

He was the principle programmer for the MPC60 and he worked with me in California. There was another fellow who designed the MPC60’s custom sampling chip and his name was David Cockerell, a very talented English guy who worked on some very famous analogue synthesisers including the EMS Synthi, as well as Akai’s S900 and S1000 samplers. I would create the overall design with the UI, screen contents and workflow, then I and my California team would write the software, David would create the sampling chip, and the people at Akai would design the details of the circuitry and mechanical parts, which they did very well in their Tokyo offices. And occasionally David and I would fly to Tokyo to coordinate with the Akai folks.

So at the time, were people like yourself, Bob Moog, Dave Smith and Tom Oberhiem networking, hanging out, working together?

I generally only saw Bob Moog at trade shows because he was on the east coast and I was in California. But Tom Oberheim, Dave Smith, Don Buchla and I were all in California and became close friends and stay in touch to this day. Dave helped me with some software on AdrenaLinn, and Tom helped fill in the gaps in my circuit design knowledge on the LinnStrument.

The Buchla synths feel as sought out as ever at the moment.

It turns out that Don’s design philosophy and workflow have become very popular and many of his ideas from 50 years ago are being reborn in new Eurorack modules by a variety of young, creative companies. His approach was less about playing musical notes on a keyboard and more about creating interesting sounds and self-generating sound patches. One fine example is a eurorack module called Maths from the company MakeNoise, which is as I understand it was inspired in part by Don’s Arbitrary Function Generator.

Do you have much interest in modular technology?

I was very interested in analogue modular synthesis as a teenager. I used to work with a popular ’70s musician named Leon Russell, whom I convinced to buy a $20,000 analogue modular system from the fledgling E-Mu company of California. It was a marvellous and fascinating learning experience, but to be honest I tired of creating a good sound and not being able to save it as a preset. Often I would simply leave it set up for a week or two for fear that once I disconnected the patchcords, I’d likely never be able to get that same exact sound again.

I actually prefer software synthesis because you can get incredibly complex and varied sounds, plus you can save whatever you create and instantly reload it any time. I value the sound of analogue and I think there are certain qualities to it that are difficult to duplicate in software, but it’s merely one form of synthesis and there have been so many new and beautiful software synthesis methods developed since then, each with its own special magic. That said, modular synthesis is far more than simply analogue subtractive synthesis, as demonstrated by the wide variety of digital Eurorack modules.

I read you demoed a prototype of the LinnDrum to Stevie Wonder, how do you gain access to an artist like that?

I grew up in LA and was a working musician and songwriter, so I knew some of the musicians and the artists they worked with. This gave me access to people like Stevie Wonder, who was known to be into synthesizers. Around 1977, he had heard about my first early drum machine prototype, which consisted of a sound generator circuit board from an early Roland beat box, connected to a computer running my software that created beats by plugging stars onto a screen grid. I went over to Stevie’s studio to show it to him, and noticed I was showing a screen-oriented programming system to a blind musician.

It made me realise that musical instruments – even electronic ones – should be more focused around sound and feel than sight. So I went back to the drawing board and rewrote the software with a real-time programming system and a physical user interface with lots of buttons, sliders and knobs, replacing the computer screen with a couple of small displays. That shift to a real time programming system resulted in my inventing timing quantisation, swing timing and loop recording, all of which are now standards in drum machines and most recording software.

Prince’s use of your first drum machine, the LM-1 Drum Computer, has been well documented. Did you share a personal relationship with him?

I never met the man, which is a shame because of course he’s no longer with us. I sent a message through his manager or roadie a couple of times and never heard back. He was apparently somewhat aloof. That said, I couldn’t ask for a better endorser because he used my drum machines prominently on pretty much all of his records. Though I never spoke to him, he spoke to me through his records.

And why was Leon Russell such an inspiration?

Leon was a very interesting guy. When I was about 17 I got a gig touring as a guitarist with an artist named Mary McCreary, who happened to be signed to Leon’s record company, Shelter Records. We started touring together and I got to know Leon, and went to work with him at his home studio in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It was a beautiful studio with a 40-track tape recorder on two inch tape which he kindly he allowed me to use for free when it was not otherwise in use.

Leon and I found a very nice synergy working together in the studio. He taught me quite a lot about music and production, and he liked my knowledge of synthesizers and recording. And though he had far better guitarists to use on his records, I was just good enough to play on his tours. He had played on tons of hit records and he knew all the top session guys, and so I got to meet these guys, hear how they play, see how they work, watch their style, watch how they could come into the studio and get it right on the first take. It was a great education. Even though I would never be the musician those guys were, it gave me an insight into what real musicians want. One thing they don’t want to do is read manuals, they just want to be able to walk up to a machine and make music, so that influenced my design style.

So it sounds like where you lived and grew up allowed you to rub shoulders with what I’d call A-listers?

To a degree, yes.

I read that you used to lug around a prototype of the LM1 to parties. Were you invited or did you just turn up packing a drum machine?

Usually I’d keep one of my drum machines in my car with me, just in case someone wanted to see it. I do recall one party I attended. In the late-‘70s there was a band called Fleetwood Mac, who started as an excellent blues band and had an incredible rhythm section drummer Mick Fleetwood and the bassist John McVie, for whom I had great respect. It turned out this band and my little company used the same financial accountant, who threw a party once that I attended. The host learned that I had my drum machine in my car and invited me to bring it in to show it to the guests, who included the members of Fleetwood Mac.

As I recall, I overheard an English woman – who may have been one of the singers in the band – jokingly say ‘it’s better and cheaper than Mick Fleetwood’. I remember Mick looking a little grumpy afterwards. Though many drummers saw drum machines as a threat, I saw them as no threat to a great rock and blues drummer like him because a drum machine can’t create a great groove nor respond dynamically to the other musicians nor perform the subtleties of striking a drum machine in a thousand different ways. Still, some drummers were very vocal about their dislike of drum machines.

Was Mick Fleetwood one of the vocal ones?

I don’t believe so, perhaps he was very famous as being one of the great rock and blues drummers. The funny thing is that I never intended to replace drummers but rather to give them a new tool to play as part of their rhythmic arsenal. I originally through that my drum machines would be used more for demos and was actually surprised to find it used so frequently in popular recordings. I thought they sounded pretty bad compared to the great drummers whose music I had grown to know and love.

So what’s your main focus now, in 2016?

I think the weakest link in electronic music is the human-computer interface, which is usually the classic MIDI piano keyboard. Specifically, people are playing music with on/off switches, which is essentially what a MIDI keyboard is. Compare this to guitar or a saxophone or a violin, instruments that have the emotional expression to make us feel and laugh and cry. My focus is on trying to create a better human-computer interface, one that can produce that level of performance expression for electronic sound, and that’s what LinnStrument is.

I’ve listened to great instrumental solos and in my view, what they have in common is the skilled continuous control of three musical parameters at once: the loudness of the note, the pitch of the note – in terms of vibrato or pitch bends – and the timbre of the note. Those are the three necessary properties, and it just so happens that in this particular universe there are three physical dimensions, which LinnStrument uses to control those three parameters. The pressure of the finger controls the loudness of the note, the left-right movement controls the pitch – slide your finger from note to note for a bend then wiggle it for vibrato – and the forward/backward movement controls timbre. So LinnStrument’s focus is the same as fine acoustic instruments – to perform expressive musical notes.

However, here’s an interesting but related topic: notes are losing popularity in favour of loops, beats and sequences as the essential building blocks of music creation, and this is the world of the DJ. I call this Object Oriented Composition or OOC. I can see the allure of being a DJ – why spend years learning notes, scales, chords, theory or expressive performance when you can simply grab someone else’s loops, sequences or beats that already contain those things? And while I do admit that many DJs do create very compelling musical works, the trouble is that there’s only so much you can do in the creative manipulation of an existing loop, beat or sequence, particularly if you didn’t create it. The odd result is that a lot of these OOC musicians wouldn’t know a note if it hit them on the head.

In fact, one of the biggest complaints DJ friends tell me is that they get no respect. People don’t view them as artists but rather as entertainers. It seems me that people expect artists to be capable of feats not possible by normal humans, and perhaps people don’t quite see the process of assembling other peoples’ loops as meeting that standard.

Since laptops have become commonplace in performance spaces now, it feels this advance in technology has brought with it a disconnect. When you see a band with drummer, guitars, bass players, you can see what they are doing. Even with turntables you know that a record is being played. But with laptop sets you don’t really have a great idea what processes are going on behind the screen.

Someone described to me once something he called ‘The Reason Scroll’, his term for a laptop performer using Propellerheads’ Reason, in which the largest physical movement made by the performer was swiping up and down on the trackpad in order to scroll between the virtual rack processors on the screen.

The odd thing is that when many DJs or OOC players see LinnStrument’s matrix of 200 RGB-lit note pads, they initially think it is simply another clip launcher consisting of on/off switches, or at best pressure-sensitive buttons as on drum pads or Ableton Push. However, LinnStrument is a very different animal, with each of its 200 note pads able to capture not just a button push or a simple single dimension of pressure, but rather all three dimensions of movement, and with full polyphony. Yes it is true that you can use it for loop manipulation – for example controlling volume, filter and pitch of a loop with one finger’s movement – but its real purpose is the expressive performance of musical notes and scales and melodies and chords. Sometimes DJs will ask if it can be used as a step sequencer or a clip launcher, and my answer is “sure, but you can do that will any cheap $200 on/off switch controller, so why buy a LinnStrument?”

How much resource and research goes into development for something like the LinnStrument.

The company is only me with no employees, but I use a number of outside resources. For example, LinnStrument and my other products are assembled by a manufacturing company in the San Francisco area. Also, most of LinnStrument’s software – which by the way I’ve released as open source – is written by a very sharp Belgian programmer named Geert Bevin, who has taken it far beyond what I originally wrote. I also have a local guy who lays out the circuit boards for me. These friends and companies permit me to get everything done while remaining a tiny company with zero employees. Though I’ll probably have to hire someone in future, for the moment I enjoy the flexibility of not having employees. The downside is I have to do everything right now, from the engineering to support to the website to taping boxes and shipping them out.

Your work with Dave Smith, was that just the result of being friends?

Yes, Dave and I have known each other for around 35 years. I’m known for drum machines and Dave is known for analogue synthesizers, so we figured it would be a good idea make an analogue drum machine together. Plus I wanted to create a drum machine with new ideas for this musical era, because my MPC drum machines are really made for how people used to make music in the late-’80s. So Tempest is a new type of drum machine, a live performance instrument for drum machinists. It’s better than something I could have made myself or Dave could have made by himself.

It seems the products Roger Linn Design release are quite grand and influential. Do you look at the bigger picture when releasing something or are you trying to chip away progressively at improving music technologies?

Most revolutions, if you look at them close enough, are evolutionary. And most overnight sensations took 10 years to get there. I could say that in many ways LinnStrument is revolutionary, but I’m standing on the shoulders of giants, most notably Lippold Haken, who in 1999 made the Continuum, the first polyphonic three-dimensional expressive music controller, and still is an excellent instrument. I’m making a better mousetrap and I think LinnStrument contains some very powerful new ideas, but if you look back even through the ‘70s, there have been many attempts at expressive controllers, mostly monophonic, mostly one or two dimensional, created by a lot of forward thinkers. Most of these instruments didn’t get much recognition at the time, it sometimes takes the world a long time to catch up to new ideas.

You’re travelling up to Bristol to accept an award for your services to music makers with special needs?

There’s an organisation in the UK called The One Handed Musical Instrument Trust, which promotes the creation of instruments and music for musicians with the use of only one hand. I hadn’t thought about it before but it is odd that all wind, bowed-stringed and plucked-string instruments require two hands to play a single note. It turns out that LinnStrument’s ability to play each note expressively with a single finger makes it well-suited for playing with one hand. So I submitted LinnStrument to this organization’s 2015 competition for the best instrument playable with one hand. They looked at a number of instruments, both acoustic and electronic, and LinnStrument won. Though I didn’t consider this benefit in designing LinnStrument, it feels very good to think that the joy I’ve experienced from music-playing can be extended to someone who has been denied that due to a physical limitation.

So on the LinnStrument, how come you didn’t arrange the keys like a piano keyboard?

I initially considered making LinnStrument’s soft rubber note pads in the shape and arrangement of piano keys. But I soon abandoned the idea because it doesn’t work well for expressive musical performance. First, the pitch intervals between adjacent white keys aren’t uniform, so pitch bends are cumbersome and unintuitive. Plus, if you want to slide from a white key to a black key, you must slide diagonally, which unintentionally changes your forward/backward position, used for total variation. And this becomes more difficult in longer pitch slides such as an octave of even a minor third, which requires either zigzag movements or results in pitch jumps along the way. Then there’s the problem of asymmetrical vibratos when the key on the left is a half-step lower but the key on the right is a whole-step higher. Add to that the fact that the piano keyboard isn’t isomorphic, meaning that a given chord or scale requires a different finger for each of the 12 musical keys.

So I looked at a variety of musical note arrangements and finally settled on the note arrangement of all stringed instruments – multiple rows of consecutive semitones, with the ability to ‘tune’ the rows however you like. LinnStrument consists of eight rows of 25 semitones – 2 octaves each – tuned by default in intervals of musical fourths like a bass guitar or the lower four strings of a guitar.

This stringed-instrument note layout solves all of the piano’s problems. As on a violin, pitch slides and vibratos are always uniform and consistent because the semitones are evenly spaced and positioned. And forward/backward finger movement – for tonal variation – is controlled independently of left/right control of pitch or finger pressure. Plus, it is fully isomorphic- to transpose pitch, simply slide your hand left or right or to upper or lower rows. You never need to learn a different fingering in order to play in a different musical key. And the final bonus is that you get five octaves in a compact, portable instrument that is only 22.5″ by 8.25″ by 1″ thin.

So is the LinnStrument one of the first products to fully adopt that grid system?

Yes, but it is part of a growing trend. Other electronic instrument makers are starting to coalesce around this same stringed-instrument note layout. It’s in Ableton Push, on a variety of iPad music apps including a very nice one called GeoShred, and of the five polyphonic expressive instruments, it’s on three of them; LinnStrument, SoundPlane and Eigenharp. I think it will gradually become the new standard note layout for playing electronic music.

It does seem odd to me that people are playing electronic MIDI piano keyboards, considering that the original reason for arranging the notes in a long single line was the need to put a string behind each key. But electronic keyboards have no strings.

A final subject is working with VSTs; you’ve done one before which was modelled on the AdrenaLinn Guitar Effects Processor. Do you plan to work with plug-ins in the future?

You’re referring to my AdrenaLinn Sync plug-in and unfortunately my co-developer on that plug-in was never able to update it for use with current operating systems and plug-in formats, so I had no choice but to discontinue it. I do still have the AdrenaLinn III, the third generation of the hardware stomp box on which the plug-in had been based.

Earlier you asked about modular synthesis and the current Eurorack phenomenon. The impetus for creating my AdrenaLinn guitar pedal was the fascination I had in my early years with using modular synthesis to process guitars through filters in rhythmic ways. Internally, AdrenaLinn is a large collection of audio processing and modulation functions, just like on an analogue modular system. You can combine the modules however you like to filter, sequence, randomize, distort, delay and otherwise modulate your guitar signal rhythmically, all in sync to its internal drumbeats or MIDI sync. So in creating AdrenaLinn, I wanted to give guitarists access to some of these wonderful sounds, but in a simple, low-cost stomp box.

Interview by James Manning

Roger Linn Design on Juno