Mike Cooper – Ambient exotica and forgotten rituals

Bringing the ambient sounds of exotica into a new age, James Manning meets with a modern day pioneer of a once fandangled style.

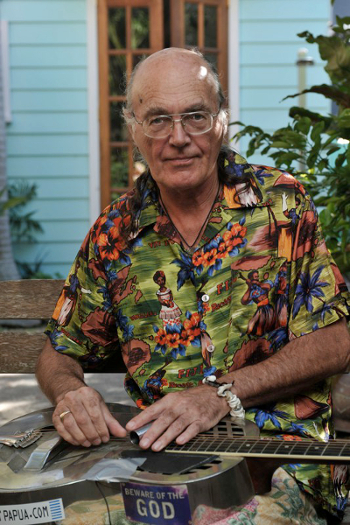

“You buy this thing, go on holiday, you go back home, it’s freezing cold, you fling it in the cupboard and never wear it again unless you go back there,” Mike Cooper says of Hawaiian shirts. He’s amassed an enviable collection over the years and the psychedelic island scenes and hibiscus prints of his box-cut shirts are as much a trademark as his lap steel guitar. “Then,”, he continues, “about 20 years later some guy decides Hawaiian shirts are fashionable so they come out of the cupboard again and they’re worth 10 times what you paid for them in the first place.”

I’m sitting in the lounge room of a flat in Mudchute, deepest East London, where Mike Cooper is briefly staying whilst on tour. It’s late-morning and over green tea with a splash of rum, talk of Cooper’s wardrobe comes up after I ask him about his album, Globe Notes. Cooper, an Englishman, has lived in Rome for 30 years and DalVerme is a bar in the city with a cellar venue he would play. This is relevant because the people in charge also run a label and have links to a publishing company associated with a free art magazine called NERO. In a collaboration, the three reissued the album as New Globe Notes 11 years after its original release with a booklet of anecdotes, poetry and cultural exploration of the Pacific. A preface for New Globe Notes was written by ambient academic and exotica enthusiast David Toop.

Three doors down from NERO’s offices stands a theatre that hosted a Mike Cooper sound installation which opened the same night as the New Globes Notes album launch; this is where the shirts come in. “I put 50 Hawaiian shirts suspended from the ceiling,” Cooper says. “I had 50 exotica record covers on a wall, tiled, and a lot of video,” he adds, “garbage and bits and pieces.” Recycling being a central theme of the installation – Cooper’s style of exotica is environmental after all – the keepsakes and reminders on show, he points out, represented “objects for forgotten rituals… dead stuff coming to life again.”

Cooper’s music, by the same token, is experiencing a renaissance; in the past two years alone, three of his albums have been reissued by three separate labels. Most recently London’s Discrepant gave new life to Cooper’s first explicitly free-improv, ambient exotica record, Kiribati (pronounced Kiribas) – named after an island slowly sinking into the ocean – while Sacred Summits, a boutique label co-run by Firecracker’s Lindsay Todd and Emotional Response’s Stuart Leath, gave White Shadows In The South Seas a glorified, screen-printed vinyl release. Lawrence English’s experimental label out of Australia, Room40, originally put out the album on CD in 2013. A chance encounter with Leath had me discover the album’s opener, “Dr. Derelict”, was essentially the reason the label indulged in reissuing the entire thing. It’s probably the best example of Cooper’s exotica you could ask for too.

Opening with the hiss and whistle of equatorial bird and insect life, an undeniable vibraphone solo enters; Cooper’s playing up there with Latin jazz musician Cal Tjader. It’s here keen ears will trace a path through the sweltering troposphere of Cooper’s wild ambience to the post-war music of 1950s exotica pioneers Les Baxter, Martin Denny and Arthur Lyman, whose melodic, tonal influences shine through a sonic flora of humid birdsong and island atmospheres. Les Baxter’s 1951 title, Ritual of the Savage, is largely regarded as the prototypical exotica record, with Martin Denny’s 1957 album, Exotica, defining the genre which took the US by storm up until the end of the ‘60s. It would, to some extent, resurface in the ‘90s as lounge or cocktail music. Les Baxter’s “Quiet Village”, later covered by Martin Denney on Exotica, is the archetypal classic.

Opening with the hiss and whistle of equatorial bird and insect life, an undeniable vibraphone solo enters; Cooper’s playing up there with Latin jazz musician Cal Tjader. It’s here keen ears will trace a path through the sweltering troposphere of Cooper’s wild ambience to the post-war music of 1950s exotica pioneers Les Baxter, Martin Denny and Arthur Lyman, whose melodic, tonal influences shine through a sonic flora of humid birdsong and island atmospheres. Les Baxter’s 1951 title, Ritual of the Savage, is largely regarded as the prototypical exotica record, with Martin Denny’s 1957 album, Exotica, defining the genre which took the US by storm up until the end of the ‘60s. It would, to some extent, resurface in the ‘90s as lounge or cocktail music. Les Baxter’s “Quiet Village”, later covered by Martin Denney on Exotica, is the archetypal classic.

“It was much more than some schmaltzy easy listening music,” Cooper tells me. “It had a lot of jazz elements and improvisation and basically they wrote music, particularly Martin Denny and Les Baxter, that was evocative of other places,” he says. “So it was ‘fake music’ in a way because it pretended to be from Bali or from Turkey or something but it wasn’t at all, it was a totally made up genre.” Add strokes of bluesy guitars, atonal and free improvisational influences, field recordings, minor synthesis and subtle dubbing and effects techniques to the stylistic tropes of the aforementioned progenitors, and Cooper’s avant garde interpretation of exotica becomes a singular vision. “Usually free jazz is associated with Afro-American,” Cooper explains, citing Sun Ra as his favourite ‘’exoticist’, and continues, “there was this stream of EU improvised music which I had more to do with; should we say experimental classical music, but it wasn’t written, it was improvised… It has a lot to do with pure sound and timbres as opposed to anything else, and I got involved in that in the late-‘70s.”

Folk and blues, to bottle neck slide guitar, may be the foundation of Cooper’s music but like he says, it’s free European improvisation which is at his core, further developed by memory of places like Fiji and travels to Hawaii, Tahiti and further down under. Playing a festival in New Zealand, Cooper remembers saying, “what’s Timor?” when asked if he wanted to go there (during the 1999 East Timorese crisis). “So I’m with my partner, and she said should we go. So we go to Darwin, get on a huge troopship, a jet full of Thai soldiers, we go in this thing, charge across and we’re in East Timor,” Cooper tells me, “it was still burning when I got there.” Cooper was there for around three weeks before catching dengue fever, “and that was the end of my aid working career.”

Mainland Australia has played a significant role in exporting Cooper’s music too, and it’s a place he’s lived in and grown to love. “There are birds in Australia that you don’t even dream about,” Cooper says, adding “when you’re from somewhere else you say, what the hell is that, so you just want to record it.” These sounds particularly stand out on his 2004 album Rayon Hula. One song of Australian reference I single out in particular, however, is “Bendigo To Kyoto” from New Kiribati which is named after a famous painting by John Wolseley. “I did a sound installation for him at the (Sydney’s) museum of modern art, so John and I became friends through that painting and that piece of music is dedicated to him.”

Australia and Cooper’s subsequent field recordings have both helped develop his live exotica performances. “I started to use those (recordings of Australia) in my improvised music gigs as another sound element, just a timbre thing, and it kind of mutated into another kind of music which came out of my free improvising but it was more of a stable part that I could in fact reproduce live in gigs if I wanted to,” Cooper says. “I wanted to make this music; I call it vertical – it didn’t go from A-to-B; there was no progression so to speak. I didn’t want it to have a harmonic progression or melodic progression, and slowly I began to put these timbres together and make this kind of vertical music, so it was kind of stable. It turned into this electronic, ambient exotica, as I called it.”

Australia and Cooper’s subsequent field recordings have both helped develop his live exotica performances. “I started to use those (recordings of Australia) in my improvised music gigs as another sound element, just a timbre thing, and it kind of mutated into another kind of music which came out of my free improvising but it was more of a stable part that I could in fact reproduce live in gigs if I wanted to,” Cooper says. “I wanted to make this music; I call it vertical – it didn’t go from A-to-B; there was no progression so to speak. I didn’t want it to have a harmonic progression or melodic progression, and slowly I began to put these timbres together and make this kind of vertical music, so it was kind of stable. It turned into this electronic, ambient exotica, as I called it.”

Cooper’s wearing clear spectacle frames, borsellino hat and a warm looking fleece when we meet; today’s colour is green. The shells looped on to his bracelet rattle during our conversation and his mellow, beachy vibe makes interviewing him feel like something between meeting Lee Perry and Crocodile Dundee. He’s in London for two gigs; his exotica performance at Dalston venue Café OTO – with Super 8 island memories projected on the wall behind him – filled the space with the kind of make believe vitamin D you’d expect to feel on the shores of a somewhere like Maui, Rarotonga or Bora Bora. It made for a nice imaginary change from the dreary reality of a cold East London that night.

“My main guitar is a 1930s instrument that’s made of metal so it’s a very specific instrument,” Cooper tells me. “You can do all sorts of things with it, even as a drum for a start, and it has various timbres all over it,” Cooper explains. He investigated “various tunings, various non-tunings, out of tunings,” on an album called Finding Other Worlds – 21st Century Guitars, while the Café OTO gig saw Cooper incorporate a small dock of electronic equipment – pedals and effects units etc – too, with his guitar gently adding strokes of languid island blues to the mix. This, alongside spoken word poetry taking in themes of travel and memory, island phenomena, local culture and the white shadows of colonial presence in the South Seas.

Cooper’s earliest forays into exotica can be linked back to his work with French guitarist and pataphysicist Cyril Lefebvre on the album Aveklei Uptowns Hawaiians. “He was one of the first people in Europe to offer tours to North African musicians and play with them,” Cooper tells me of Lefebvre. “We (including Lol Coxhill, Steve Beresford and Ollie Blanchflower) were a modern version of a long line of eccentric British Hawaiian bands I suppose,” Cooper says. “The band only played one concert in the UK at the ICA when I organised a 100 Years of Slide Guitar festival there,” Cooper says, “we toured and played in Europe but England didn’t seem ready for us.” Cooper’s “seriously avant-blues” band Continental Drift is one of many other groups he would mention during our meeting along with his 20 year tenure in The Recedents and projects even further afield like playing avant-rembitika (urban Greek folk music) with Viv Corringham. But when it came to his exotica-inspired music, Cooper concedes, “the non-event of these bands and records in the UK was part of the reason I was happy to leave.”

Cooper’s first record was a four-track 7” released on Pye Records in 1965 made with guitarist and singer Derek Hall; the two had a residency at a coffee house in Reading where they’re from, and after impressing on those recordings Cooper was offered a contract and second album. “Pye Records at the time was a very mainstream, middle of the road record label,” Cooper begins. “You had people like Max Bygraves, he was a mainstream, easy listening guy who you might have heard on the radio in the ‘50s, not even in the ‘60s,” he says, chuckling. “I’d been playing the folk club circuit, playing blues for about seven years by then, so I was pretty much on my way to something or other,” Cooper remembers, then adds, “I was interested in doing something else, moving on…playing some different music.”

Pye Records then launched Dawn Records with Mike Cooper as its first artist. “All these other labels had these progressive bands on there, these rock bands that are gonna do something else, so they start Dawn records,” Cooper explains. “I said I’d really like to make a record with jazz musicians as my backing,” he says, “I said I want to make songs with jazz musicians because they will do something else with it that rock guys won’t do.” Cooper ended up doing three records for Dawn which were all reissued last year by the American label Paradise Of Bachelors, including the album Trout Steel which is considered by many as a seminal work.

“I have this strange ability, apparently, to make strange psychedelic music… I’ve never been a drug taker in my life.”

Paradise Of Bachelors is also home to the music of Steve Gunn, an American guitarist Matt Werth’s RVNG Intl. put up in a Lisbon villa for 10 days to record a collaborative album with Cooper. Entitled, Cantos De Lisboa, the album was part of the FRKWYS series which pitches respected elder musicians with younger artists of an equivalent nature, with Gunn and Cooper enjoying some time away in the Portuguese sun along the way. Other collaborations in the series include Philly duo Blues Control’s hook up with meditation guru Laraaji, spiritual journeyman Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe’s meeting with new age zen master Ariel Kalma to Smalltown Supersound artist Arp’s collaboration with British experimental music composer Anthony Moore.

“I had no idea who Steve Gunn was,” Cooper admits, and with little to no idea about RVNG Intl either he asked if Werth could send him some kind of reference to understand the ways of the New York label. Werth sent Cooper the ninth FRKWYS album, Icon Thank Me by Sun Araw & M. Geddes Gengras Meet The Congos. “I love The Congos,” Cooper tells me, “I went yeah, I mean you’re doing something with those guys: I’ll work with you.” Even though both artists play the guitar, Cooper admits at first he was a little unsure about how the project would work out. “I do the free improv stuff and everything, and Steve does his finger picking post-John Fahey type of guitar,” Cooper explains with no hint of dismissiveness. “I wasn’t going to start finger picking that was something I left behind years ago,” he says.

Be it in the jazzy, micro-atonal twang of his industrial avant garde LP, Light On A Wall, to other nebulous exotica works like Rayon Hula, improvisation is something you’ll hear throughout Cooper’s work. His improvisational streak becomes all the more clear on music he’s made with traditional instruments, but dive deeper into the whistling wildlife and woozy slide guitars of his exotica and you’ll find elastic rhythms, delayed or simultaneous, as nature itself. Cooper’s often dense thickets of amorphous sound design go great lengths to transport the imaginations of 1950s exotica composers to the modern day. Like Cooper, they would use bird calls and insect sounds to make their music even more evocative of ‘another place’ – a tropical place.

The Dutch jazz musician Ab Baars once told Cooper his music reminded him of being a child in Bali, half asleep in an open vehicle surrounded by strange sounds moving through the countryside. “I wanted to pursue that idea, that dreamscape, slightly surreal,” Cooper explains, “it reminded you of actually being somewhere you’ve never actually been but you might think you’ve been there, or even wanted to go there even.” Pairing anecdotes of sound, travel and memory with Cooper’s music is naturally what hits his artistic sweet spot.

“I have this strange ability, apparently, to make strange psychedelic music… I’ve never been a drug taker in my life,” Cooper tells me in his warm, pleasant tone, “When Trout Steel came out I had people writing to me saying, ‘what do you take, this record is so psychedelic?’… I have no idea, must be something in my head.” It would be easy to paint Cooper as something of a hippy dippy beatnik forever trawling the Pacific for trinkets, cheap artefacts and memories to hang from someone’s ceiling. But with music on his overlooked Hipshot label still a fresh grounds for labels to discover and rerelease new music, Cooper’s so far ahead of the times he’s back in fashion.

Interview by James Manning

Header image courtesy of Valerio Mannucci and Nero Publishing

Mike Cooper Beware Of The God image courtesy of Greg Clovelly

B&W live image courtesy of Cafe OTO