Nothing Short of Total War – The Blast First story

Ian Maleney tracks down Paul Smith, founder of the Blast First label and its successor Blast First Petite, and responsible for facilitating the rise of everyone from Sonic Youth to Pan Sonic via HTRK.

Speaking to Paul Smith, you get the sense that not even he can quite believe the life, and the luck, he’s had. The brogue of the small mining town in the northwest of England where he was born in the mid-‘50s is still noticeable. He retains a strong work ethic inherited, or so he claims, from his mother. By his own admission he was a late starter, turning 26 before he had any idea of what he wanted to do in life, but once he figured it out, there was no turning back.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Blast First, the label Smith founded in order to release Sonic Youth’s music in Europe. It’s sobering now to look back and contemplate the acts the label was working with, even just in its first five years in action: Sonic Youth, Big Black, The Butthole Surfers, Dinosaur Jr., Sun Ra, Head of David, UT, and Glenn Branca. “That run of bands is just fucking insane if you look back on it now,” Smith says, and he’s not fucking wrong either.

While Smith’s life would take many unexpected twists and turns, the roots of Blast First can be found in Nottingham in 1982, where he was working for the Nottinghamshire County Council. He had a partner, and a mortgage. So far, so deathly normal.

“The guy who I worked opposite, who was past his retirement age but didn’t want to leave – absolutely beautiful hand, he used to draw things, absolutely fantastic hand – but he was writing up the menus for after the apocalypse for the Seventh-Day Adventists,” Smith says. “So I know prawn cocktail is the starter for the day after the apocalypse for the Seventh-Day Adventists. I think if you’re relatively young and you see that opposite you, you go, ‘Yeah, don’t think I want to end up in that situation, maybe I’ll do something else’.”

That something else arrived in the form of Cabaret Voltaire. In 1982, Richard Kirk and Stephen Mallinder were working out of their studio in Sheffield, and Smith got to know them after exhibiting – and cutting short – a video of theirs at an event he’d hosted in Nottingham. Together they started Doublevision, an innovative VCR label that released strange DIY music films for bands like Throbbing Gristle, 23 Skidoo and The Residents. Smith rented video players and copied them at home in the evenings after work. After realising their releases weren’t getting reviewed in the music papers, Doublevision started to release the music from the videos on LP as well, which helped spread the word.

The LPs were distributed, as were pretty much all independent records in the UK at that time, through Rough Trade. It was on a trip down to London to meet the Rough Trade staff – which meant lunch-time drinks at the legendary Malt & Hops pub – that Smith heard about the Fifty One-Page Plays which Lydia Lunch and Nick Cave had written together, and thought they’d make a great Doublevision release. Smith went to visit Lunch in her flat, found her recently separated from Cave and dying to get out of the country, so the plays weren’t going to happen. Lunch did, however, have the backing-tracks for a full album under her bed; all they needed was vocals. After talking it over with Kirk and Mallinder, Lunch was brought up to Sheffield to record the vocals for what would become In Limbo, and given a one-way ticket back to New York as an advance. Back in the U.S., Lunch told the young guitar player who’d played on In Limbo about a guy in England who “wasn’t a complete arsehole”. That guitarist was Thurston Moore, and he sent Smith a cassette copy of an unfinished album by his band, Sonic Youth.

The LPs were distributed, as were pretty much all independent records in the UK at that time, through Rough Trade. It was on a trip down to London to meet the Rough Trade staff – which meant lunch-time drinks at the legendary Malt & Hops pub – that Smith heard about the Fifty One-Page Plays which Lydia Lunch and Nick Cave had written together, and thought they’d make a great Doublevision release. Smith went to visit Lunch in her flat, found her recently separated from Cave and dying to get out of the country, so the plays weren’t going to happen. Lunch did, however, have the backing-tracks for a full album under her bed; all they needed was vocals. After talking it over with Kirk and Mallinder, Lunch was brought up to Sheffield to record the vocals for what would become In Limbo, and given a one-way ticket back to New York as an advance. Back in the U.S., Lunch told the young guitar player who’d played on In Limbo about a guy in England who “wasn’t a complete arsehole”. That guitarist was Thurston Moore, and he sent Smith a cassette copy of an unfinished album by his band, Sonic Youth.

“I can remember to this day, I could make the film, I could draw the picture of exactly where I heard it, what the weather was like,” Smith says. “I mean, it was an absolute epiphany for me in one of those weird, pseudo-religious things that you never think is really going to happen to you, but I was absolutely drawn into that world immediately.”

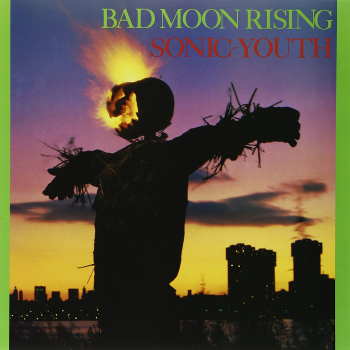

Smith took the cassette to the Cabs with a mind to release it on Doublevision. They turned it down; “too rock and roll.” After badgering every regular in the Malt & Hops for a few weeks, Peter Walmsley of Rough Trade eventually caved and offered Smith a manufacturing and distribution deal, if he could get the rights to the album. Smith maintains the deal happened only because Arsenal was playing and Walmsley, a die-hard Gunner, wanted Smith to shut up so he could concentrate on the match. It was one of the last such deals done by Rough Trade, which was in the process of becoming a far more corporate outfit under the guidance of Simon Harper. This Sonic Youth tape became Bad Moon Rising, and was released in 1985 with the catalogue number BFFP01.

By the time the label’s third release, Sonic Youth’s Flower/Halloween single, appeared a couple of months later, Blast First had already begun to fall out with Rough Trade. The cover of the 7” – a sort of Raymond Pettibon approximation with a topless model – put paid to the brief relationship altogether. At the time, Rough Trade were booking Abbey Road for Shelleyan Orphan; it was only a matter of time before the two had to part ways. With an early copy of Sonic Youth’s next LP, Evol, in his back pocket, Smith needed to find a new home for Blast First. Mute boss Daniel Miller, rich on the proceeds of Depeche Mode and Yazoo, offered him a deal and space in their new offices on Harrow Road. From this base, things really started to get going – John Peel would soon call Blast First the “most important label of the age”.

Key to the label’s success was a list of bands that Moore had brought with him on Sonic Youth’s first visit to England, having thought he was about to meet a real record label executive. Instead, he got Smith, who set about trying to sign and release music from all the bands on Moore’s list anyway. Sonic Youth’s relentless touring across the America in their early years made it seem like they knew just about every good band in the country, and Smith soon found himself in touch with Big Black, The Butthole Surfers and Dinosaur Jr. The latter were a personal recommendation from Kim Gordon, who left a demo-tape of Bug under Smith’s pillow.

Key to the label’s success was a list of bands that Moore had brought with him on Sonic Youth’s first visit to England, having thought he was about to meet a real record label executive. Instead, he got Smith, who set about trying to sign and release music from all the bands on Moore’s list anyway. Sonic Youth’s relentless touring across the America in their early years made it seem like they knew just about every good band in the country, and Smith soon found himself in touch with Big Black, The Butthole Surfers and Dinosaur Jr. The latter were a personal recommendation from Kim Gordon, who left a demo-tape of Bug under Smith’s pillow.

Though there were some British bands on the label, Blast First became known for releasing the best in American post-hardcore, as well as being an endeavour powered by booze, amphetamines and a palpable disdain for the increasingly professional world of independent music. Liz and Pat Naylor, described by Smith as “two hardcore lesbians who hated male music journalists,” were in charge of PR, and their remarkably brusque approach generated yards of coverage in the music press. One press release was an entire A4 page covered with a rant by Pat Naylor about the travails of supporting Derby County F.C., with one line at the end about the fact that Big Black had a new album out that week. It was reproduced in full by NME.

The label was building up a large fan-base, and bands like Sonic Youth and Big Black went from playing in front of a hundred people to several thousand in just a couple of years. To Smith’s disgust, people were buying the records simply because he was putting them out.

“We started getting letters from some people saying, ‘We buy everything on Blast First’,” he says. “That’s when I started putting out Sun Ra and Glenn Branca and a few other things because, while I speak highly of the methodologies of Tony Wilson, I didn’t want a Factory Records where people bought everything just because it was on Factory.”

The plan worked well. “Literally within a couple of months of getting those letters and putting out those records, which I probably would have put out anyway, then we got a slew of records back, saying ‘What is Sun Ra? What is this shit?’” This was exactly the reaction Smith was after, “I was like, ‘great, have your money back but you know, don’t go around following people’. That’s just not that smart to do that, and I didn’t want a cult in that sense. It’s not good for your ego if you have a run of bands and you start believing that you really do know what you’re doing. I really didn’t know what I was doing.”

Whether he did or not, the label had momentum. With Smith’s help as label-head, manager, van-driver, sound-engineer, merch-dude and a host of other jobs, Sonic Youth had grown into a major label prospect and the release of Daydream Nation in 1988 cemented their reputation. Blast First had released the album in America themselves, a first for the label, because the band suspected SST – Sonic Youth’s American label, run by Greg Ginn of Black Flag – of having some dodgy accounting practices. It was to be Smith’s last significant role in the Sonic Youth story. After months of awkward courtship in the fancy Manhattan offices of the major labels, Sonic Youth found themselves signed to Geffen for the release of their next album, Goo. Smith, whose all-encompassing relationship with the band was still largely undefined, found his Malt & Hops way of doing things most unwelcome in the board rooms of New York and, though no member of the band ever told him he was fired, he was definitely fired.

After Sonic Youth jumped ship, Nirvana-fever gripped the music world and the music Smith had championed five years earlier was reaching an unimaginable audience. By 1991, Blast First had lost most of their biggest acts to majors: Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr and the Butthole Surfers had all moved on. Big Black had inevitably packed-up and quit at the height of their success, a move that surprised no one who knew Albini. “Acceptance would be the worst possible thing I think for him, under those circumstances,” says Smith. “If they’d stayed together, I’m convinced they could have been AC/DC. They could have been that good, if they stayed cranking along in that way. But that was never likely to happen, from the personalities of Big Black.”

After Sonic Youth jumped ship, Nirvana-fever gripped the music world and the music Smith had championed five years earlier was reaching an unimaginable audience. By 1991, Blast First had lost most of their biggest acts to majors: Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr and the Butthole Surfers had all moved on. Big Black had inevitably packed-up and quit at the height of their success, a move that surprised no one who knew Albini. “Acceptance would be the worst possible thing I think for him, under those circumstances,” says Smith. “If they’d stayed together, I’m convinced they could have been AC/DC. They could have been that good, if they stayed cranking along in that way. But that was never likely to happen, from the personalities of Big Black.”

While Sonic Youth and Nirvana were blowing up, Rough Trade was falling apart. Blast First were still a sub-label of Mute, who put out records in the UK through a mastering and distrobution deal with Rough Trade. When Rough Trade began to collapse, Mute found they were owed somewhere north of a million pounds. Mute managed to survive the collapse, largely thanks to their success outside of the UK, but many of the smaller indies associated with Rough Trade – as well as ‘The Cartel’, a tight-knit group of record shops which stocked and sold Rough Trade records – folded. In short, it was a time of cataclysmic change for the British independent music scene, when many of the DIY structures built over the last decade creaked and eventually gave way under pressure from the mainstream markets. Indie music was big business now, and with Oasis and Blur soon to rise, it was only getting bigger. Whether as a result of this upheaval or just because of Smith’s personality, Blast First seemed to be moving in the opposite direction.

Blast First worked with The Afghan Whigs for a couple of weeks – during which they released their best album, Gentlemen – but this was as close to the mainstream as the label came in the ‘90s. In general the music was getting weirder, and the guitars were disappearing. Releases from F.M. Einheit, Casper Brotzmann and Phil Niblock maintained Blast First’s avant-garde credentials, while Smith was also involved in a multi-media club night called Disobey, alongside Russell Haswell and Bruce Gilbert. It was at a Disobey night, in New York in early 1995, that Smith first saw Pan Sonic play.

Smith had heard of the Finnish duo through a former Rough Trade employee who was working at a techno distributors in New York. After being blown away by the first couple of Sähkö 12”s he sent a fax to the number on the back of the record, effusively wondering if they might be able to work together. In Finland, Tommi Grönlund threw the fax in the bin. By chance, Mika Vainio arrived in the office, happened to see the Blast First logo in the bin, and dug it out. A conversation was started that led to Smith flashing “the Mute Am-Ex card” to bring Pansonic to New York. The line-up for that Disobey night in the Knitting Factory also included Aphex Twin putting a 12” piece of sandpaper on a turntable and playing it over the PA for ten minutes. Needless to say, Pan Sonic had found themselves a home, and they would go on to release nine LPs (not including a hatful of singles and solo efforts) through Blast First.

Through the ‘90s, Mute remained a successful label, culminating in the global success of Moby’s Play. Behind the scenes though, Daniel Miller was beginning to run out of steam, feeling that the music industry had changed into something he wasn’t comfortable being a part of. “The whole Britpop thing fucked it up for me,” he later said. In 2002, he sold the label and all its assets – including Blast First – to EMI. While EMI were interested in the back-catalogues of bands like Depeche Mode, they had less time for the likes of The Mekons and AC Temple.

“I had no problem with the idea that Daniel wanted to sell the label but I also knew that was a death knell because Blast First had nothing to offer EMI,” Smith says. “Well first it was EMI and then it was Terra Firma who were a bunch of bankers from London who weren’t buying EMI so they could stroke the Beatles masters, they were just buying it as an investment. Then they couldn’t pay their bills, so for a while Blast First was owned by the Bank of America, which, nobody’s talking about guitar solos there mate.”

Blast First is now in the hands of Sony/BMG, and not a whole lot is happening with it. Instead, Smith has created what he calls, “a faster response unit, an ambulance, if you like.” Blast First Petite is a fully independent label, operated by Smith alone. Its releases are often smaller projects by well-known artists like Suicide, The Slits and Mika Vainio, most of which wouldn’t stand a chance of getting released through a major. Others, like Outer Space, Michael Chapman and Forrests, are just beautiful one-offs that Smith felt needed releasing. Some bands who release on the label, like Factory Floor or HTRK, will also be managed by Smith for a time, who sees it as his duty to get them a better deal elsewhere. It’s a sort of half-way house, a platform for bands where bands can get records out and hopefully move on to bigger things. With over three decades of gigs, releases and pub-chat behind him, Smith’s industry contacts are a help to any young band.

At 58, and having survived what he calls “a massive heart-attack”, Smith has license to feel somewhat nostalgic for days past. He suggests he’s “rapidly becoming a very old man”, and many of the people he’s worked with, from Rough Trade warehouse staff to best-selling artists, are also getting on in life. Good friends like Iain Sinclair and Alan Vega are over 70 now, and he mentions the names of several people who have died in recent years, including Peter Walmsley, who gave him his first deal with Rough Trade. In search of clean air and more time to listen to music, he and his wife, Susan Stenger of Band of Susans, moved to a rural part of Cork, on Ireland’s southern coast. Looking back on his first involvement with Doublevision and Sonic Youth, it’s clear to him that times have changed.

At 58, and having survived what he calls “a massive heart-attack”, Smith has license to feel somewhat nostalgic for days past. He suggests he’s “rapidly becoming a very old man”, and many of the people he’s worked with, from Rough Trade warehouse staff to best-selling artists, are also getting on in life. Good friends like Iain Sinclair and Alan Vega are over 70 now, and he mentions the names of several people who have died in recent years, including Peter Walmsley, who gave him his first deal with Rough Trade. In search of clean air and more time to listen to music, he and his wife, Susan Stenger of Band of Susans, moved to a rural part of Cork, on Ireland’s southern coast. Looking back on his first involvement with Doublevision and Sonic Youth, it’s clear to him that times have changed.

“It was the idea that you, Mr. Nobody, could do something with a gap and make something of it,” he says. “It’s the making things happen, if I think about it, that fascinated me. That you could make things happen. There was something about that time, slightly post-punk, where sort of being able to manifest your destiny was quite an important thing. I’m not too sure anybody spends their time doing that these days. To have that ability to change your life is a different thing.”

Smith’s recent projects, whether screening seventy films across London with Iain Sinclair (and publishing a book about it) or releasing records from bands like Nissenmondai, suggest that, 30 years after he first started putting out records, there is still no grand plan at work. He is still on some “King Arthur-like quest for some other grail,” and at the heart of this most idiosyncratic life in music there remains a firm grasp of just how unlikely, improbable and downright ridiculous the whole adventure has been.

“I’ve never wanted to be in the ‘music business’, in the meaning of that word ‘music business’,” he says. “My mum is long gone, but where we came from, I’ve an elder brother and he’s a cost accountant. My poor mum would constantly have this thing of like, ‘What do I tell the neighbours that you do?’ and I’d go, ‘Well, I’ve got this little record label’. And she’d go, ‘I can’t tell them that! Nobody from around here’s sons have little record labels.’ So I ended up saying, ‘Tell them I drive a van with equipment in, for musicians’. And she was quite comfortable, that seemed plausible to her. Don’t get me wrong, she was not an unloving mother or any of those things. But within the landscape she existed in, then it was just ridiculous that you would do this thing. I always like to try to cling onto the ridiculousness of having that opportunity because I would not have put any money on my life having turned out the way it has.”

Interview by Ian Maleney

Blast First Petite on Juno