Bugging the System: An interview with Tom Bugs

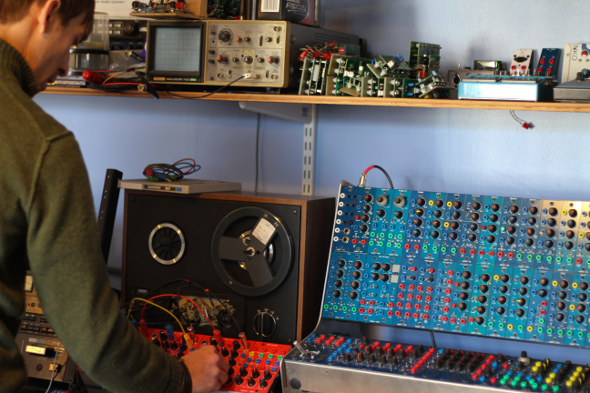

Oli Warwick descends on the Stokes Croft lab of Tom Bugs, the man behind BugBrand’s array of modular synths and sound devices, which count Bass Clef and Omar S as fans.

In the multifarious landscape of music technology there exists a land beyond the mountainous marketing campaigns and rehashed old favourites of the hardware giants. It’s a densely populated forest of smaller manufacturers with their niche products and dedicated followings, not least in the field of modular synthesis. As Analogue Solutions’ Tom Carpenter explained when we spoke to him in 2013, “It seems every man and his dog now makes modules, and it’s getting to the point of a massive overlap in what they do.”

It’s the perfect unregulated atmosphere in which a maverick can rise to prominence, unbound by tradition, production or market pressure, seeking only to entertain his own curiosity about sounds and circuits, and that’s just how BugBrand has taken shape as a thrilling outlet for quality, handcrafted sound modules and devices. The difference is that Tom Bugs’ life’s work stands apart from the madding crowds of modular enthusiasts through his unique approach to design and implementation, drawing in a crowd of dedicated followers eager to obtain one of his limited-run creations.

BugBrand operates out of a workshop in the shabby, creatively-thriving Stokes Croft area of Bristol, but the reach of the company is global. Through years of interaction and contribution to the culture of specialist message boards such as Muff Wiggler and Electro-Music, Tom has raised awareness for his work, leaving new products for mere minutes on the (digital) shelf before being snapped up by keen gear fiends. It’s a combination of playful, intuitive interfaces, a desire to further sonic experimentation and appealing aesthetics that have made BugBrand products so desirable; while arguably the small-scale production runs that Tom turns out create even more interest through scarcity.

Like so many, it started for Tom with early explorations under the hood of basic keyboards and synthesisers, having edged away from a classical upbringing to messing around with a Casio CZ101 in a band. After enrolling in a degree in Music Systems Engineering in 2000, Tom found himself less enamoured with the rigid mathematics of his course and more intrigued by the circuitry of sound devices. From looking at the primitive designs of David Tudor in the library to picking up discarded Speak & Spell toys from car boot sales, a fascination with the murky world of circuit bending was formed.

The first BugBrand design stemmed from this combination of extra-curricular research and a love of unhinged noises. The Weevil has gone through many different mutations, staying with Tom since he started making audio devices through to the present day, but the design has always stayed true to simple circuits fuelled by a pair of oscillators with contact points and power starvation as the ingredients for wild sound generation. In essence they are purpose-built circuit bending devices, and they set the ball rolling for BugBrand to take shape.

“Just as I finished university I did my first batch of Weevils with these orange boxes and started selling those to various people,” Tom explains as we talk amongst the electronic jumble of his workshop. “The last one I put up on eBay went for two or three times as much as I’d been trying to sell them for. That made me think this might be something to carry on doing.”

A lot of the interest was coming from Scandinavia, still the strongest territory for Weevil purchases, spearheaded by interest from celebrated Norwegian noise artist Lasse Marhaug and Swedish free jazz saxophonist Mats Gustafsson. While there were myriad Weevil designs from beautiful cigar box casings to exposed circuit board postcards, the most outlandish must surely be the Weevil Saxophones Tom was commissioned to create for Gustafsson and Dror Feiler in 2005. Using the saxophone as a vessel for a microphone and various sensors and contact points, the idea may have been exciting but Tom has mixed feelings looking back on it now.

“[The saxophone] was a step too far,” he admits. “The interface certainly didn’t capture the power with which they play the saxophone. I’d definitely do it in a different way. Much of the circuitry I didn’t have a clue about at that stage.”

The raw unpredictability of the Weevils is something that Tom has gradually moved away from, largely due to the creative constraints that come from working with such anarchic devices. “Turning on a machine that is kind of chaotic and you can’t really control… it’s different from someone who is a virtuoso and has practiced a lot and then moved from being a noodler to squawking and squealing,” Tom explains. “Noise music tends to be where the Weevils get used. It was something I was interested in to some extent, but any project I’ve got to have some interest in and personally now I don’t just want to be cranking out noise makers.”

The raw unpredictability of the Weevils is something that Tom has gradually moved away from, largely due to the creative constraints that come from working with such anarchic devices. “Turning on a machine that is kind of chaotic and you can’t really control… it’s different from someone who is a virtuoso and has practiced a lot and then moved from being a noodler to squawking and squealing,” Tom explains. “Noise music tends to be where the Weevils get used. It was something I was interested in to some extent, but any project I’ve got to have some interest in and personally now I don’t just want to be cranking out noise makers.”

At present Tom’s latest run of products are centred on the DRM1 Major Drum unit. The DRM1 makes for a neat encapsulation of what appeal BugBrand products carry. The tones that emerge from the unit can reach from sharp, accentuated percussive blasts to rounded, globulous tones that would make a booming 808 kick bow in deference, with the characteristics of the sounds instantly malleable through the comprehensive interface. It’s a surefire way to get distinctive rhythmic sounds beyond the well-trodden path of de-rigueur drum machines.

Rhythm has grown to be a key focus for Tom, not least through his work in modular synthesisers, where a non-standard attitude towards clock divisions and a general disinterest with straight 4/4 timing has led to some highly desirable sequencer modules. A new standalone sequencer unit is in development at present for the DRM1, but it’s through his modular work that Tom has gotten to grips with more developed manufacturing beyond the raunchy randomness of the Weevils.

“I’ve learnt much more electronically working on the modular stuff because the circuitry there is that much more stable and evolved,” Tom explains. “If you patch it in particular ways then it is capable of all sorts of chaos but its basis is much more refined. I generally now prefer stable circuitry that can be pushed rather than relying on weird quirky stuff.” It wasn’t a quick process, but much like the appeal of modular set ups for users, the open-ended nature of the technology spoke to Tom’s free spirited approach to engineering.

“The way I’ve developed my modular system is that everything is pretty much a constant amplitude which means in theory you can patch freely and you won’t constantly be coming up against connections that don’t work,” he explains. “It’s a general life approach; be open to the changes. All these little things come along, how it develops, there’s no particular rhyme or reason. Somebody gave me this 606 that was broken and it took me three years to figure out how to mend and now I really like the 606. I didn’t like drum machines initially.”

While he might not have been the biggest fan of box beats to begin with, the modular work increasingly edged Tom towards an interest in the rhythmic side of his craft rather than just the tonal qualities, and in doing so he has developed a unique line in sequencers with clock dividers that work from simple eight step arrangements into intricate patterns through clever sub divisions. While he can happily wax lyrical about the joy to be had in shifting rhythms back and forth, those who have been working on BugBrand modular rigs are equally well placed to comment.

“The thing that really sets the BugBrand stuff apart is the sequencing side,” enthuses Ralph Cumbers, best known as Bass Clef and increasingly as Some Truths. “He has totally amazing clock dividers and sequencers, like nothing else I’ve ever used, and which are perfect for the kind of ever-changing repetitive non-repetitive stuff I like to do most.” Ralph’s experience with BugBrand equipment is more fleeting than most. While he and Tom knew each other from years spent crossing paths in Bristol, it was a chance encounter in London that led to Ralph borrowing a two-frame modular rig for a little over a week before running it back to Bristol while on a mastering errand.

“I basically had about 8 or 9 days and nights,” Ralph recalls. “I hardly slept or saw anyone or left the house and did twenty four tracks in the end. A super intense period of joy and work.”

That crash course on Tom’s rig gave rise to two releases just seeing the light of day now. One is the new Some Truths LP on Mordant Music, and the other is the BugBranded EP as Bass Clef on Public Information. Ralph is no stranger to modular work, having his own Doepfer-focused set up, and Tom was well aware of this before lending him a rig.

“When he started doing the Some Truths stuff with the modular, I think I saw one of his first live shows and really enjoyed it,” Tom recalls. “We bumped into each other every so often and obviously he’d been like, ‘would love one of your systems, never gonna be able to afford it’, so it just seemed so right to lend somebody like Ralph this system and see what he came out with, and he took to it like a duck to water.”

Tom is always motivated by the creative application of his creations, to the point where what happens after his hardware has left the workshop is just as important as the build itself. As is the case with these two releases from Ralph, knowing that his hardware has been immortalised on vinyl is a constant motivation for Tom in his work. “There’s the object that I made,” he says, “but also I don’t just want it to be lots of SoundCloud noodles that will probably disappear after a while. I like the idea of Ralph’s things coming out on vinyl. Here’s something that is real. It’s quite a driving force for me.”

Ralph isn’t the only artist to have benefited from Tom’s benevolence in lending out a valuable amount of modular equipment. Alex Omar Smith, known to most as Omar S, first heard of BugBrand when Tom was delving into more rhythmic electronic music and wanted to buy a raft of vinyl direct from the Detroit-based artist. After mentioning his handiwork while making the deal, a meet up in London was arranged around one of Alex’s gigs.

“My experience with synth guys and collectors is they’re always weird, fat as hell, and have no girlfriend,” recalls Alex, “but when I opened the door of my hotel room it was a normal looking person with a briefcase. I thought he was one of the hotel staff until he introduced himself. Shit blew me away!”

“It was in the ongoing development of the portable systems and I put it together thinking, ‘this will be a lending system’,” Tom explains, “and took it to Alex saying, ‘we’ll work out a way like you borrow it for a few months,’ and as soon as I walk through the door he’s like, ‘man, put me on a payment plan!’”

With their shared love of the Roland 606 and the Korg Monopoly, it made introducing Alex to the ways of his modular more logical for Tom. Once the rig was across the Atlantic in Detroit, Tom put together some instructional videos (which can be found with some canny You Tube searching) to demonstrate what Alex could do with the modular alongside his existing set up.

“First the colors grab you,” Alex says of the appeal of BugBrand, “then syncing to other devices is easy. Then the sound of the envelopes, filters, delays, Bug Crusher and all the waveform shit things. I don’t still understand all that shit, so I just hook shit up and record you know?”

“I’m so tied up in it I think, ‘ah it’s quite obvious’,” Tom says of how easy it is to take to the modular, “but then actually some people work by adjusting until they think ‘this sounds good’, not making things technical.”

Following this initial link up, Tom and Alex kept in contact and the next time Alex came to Bristol for a gig they linked up at Tom’s studio for a jam. While Alex promises a “hit record” from their shared sessions will be coming soon on FXHE, Tom has already had his own release out on the label, which arose from a spur-of-the-moment recording one evening while testing out a new bit of kit.

“I’d just got the Roland JX3P and so was fucking around with it, using the modular to clock it,” Tom explains. “I thought, ‘there’s some really nice bits in here but how would I edit it?’ When Alex was here I gave him a couple of things, that being one of them, and he got back in contact and said, ‘I really like this, we should just put it out as it is’.”

“I’d just got the Roland JX3P and so was fucking around with it, using the modular to clock it,” Tom explains. “I thought, ‘there’s some really nice bits in here but how would I edit it?’ When Alex was here I gave him a couple of things, that being one of them, and he got back in contact and said, ‘I really like this, we should just put it out as it is’.”

It’s not the first time Tom has been released, having had his Knowledge Of Bugs project active around Bristol between 2001 and 2006 as well as collaborations with other local bands. However he naturally slid towards the electronics and so the music started to take a back seat.

“There was a clear realisation that being a musician was a difficult thing and actually I don’t think I’ve got the skills at all to make a living doing that,” Tom comments somewhat self-effacingly, “and instead of recording releases it’s as though I’m doing hardware releases that contain all sorts of different things but get to be different whoever gets them.”

It’s clear that Tom isn’t done with making his own music, as his impressive studio set up demonstrates. As well as his own devices there is a plethora of drum machines and synthesisers spread across the room, and while demonstrating his hardware in action it doesn’t take long for the beginnings of a track to take shape. However throughout our conversation Tom constantly refers to the ogre of time that looms large in his life, lamenting the lack of opportunity to sit down in the studio while also acknowledging his own culpability in getting too easily distracted by new toys to play with rather than sticking to a specific set up with which to make something. It’s a conundrum that affects both his workshop output and his studio work.

“One thing with modulars I always thought was a problem,” he starts, “with anything you need to have limitations, and with modulars when there’s always new stuff coming out and you’re like, ‘oh maybe I should get one of these’, and you’re not making music. In some ways I’m driving that problem! I need to remind myself as well to settle on a set up and actually finish some stuff for once.”

As such, Tom is shifting the focus of BugBrand away from developing modules to concentrate on the devices such as the DRM1. While a sequencer and an expander for the drum unit are near completion for a production run, other units have included a couple of versions of the PTDelay effects box and the PEQ parametric equalizer, which met with a rapturous response from buyers including Kevin Martin (quite apt considering Martin’s most noted project is The Bug).

The same intuitive layout and creatively rich signal pathways remain, placing these devices beyond the more constrained application of similar products and opening up the possibilities for imaginative and original sounds. It’s the grounding principle that has guided the development of BugBrand since the first Weevils started chirping through their oscillators. While Tom wants to open up the accessibility of his work to reach beyond those locked in to his modular system, still the problem remains of supply versus demand.

The same intuitive layout and creatively rich signal pathways remain, placing these devices beyond the more constrained application of similar products and opening up the possibilities for imaginative and original sounds. It’s the grounding principle that has guided the development of BugBrand since the first Weevils started chirping through their oscillators. While Tom wants to open up the accessibility of his work to reach beyond those locked in to his modular system, still the problem remains of supply versus demand.

“I don’t know whether I’m guilty of stirring things to make it seem more special,” he muses, “because I’ve only ever done batches and sold when things are ready. I want things to be regularly available and I don’t want people to be frustrated, I don’t believe that hype is helpful on things. I’m my own worst enemy. I’m meant to be finishing these things off but I’ve also got to think what the next step is to keep things flowing anyway.”

While he was able to bring himself to outsource the manufacture of his circuit boards to alleviate some of the workload placed upon him, he’s ever reluctant to relinquish too much control over the product, like any proud craftsman. He says, “I have a friend whose job it is to streamline electronics businesses and he’s come in here and said, ‘why are you still doing everything in house?’ but I like doing things like this. I like small scale runs of things with character. The idea with my stuff would be to get the product finished and solid so that I can outsource it, but of course I never let it get to that stage.”

That’s why each notable design in his repertoire has gone through multiple incarnations that he tweaks with each batch, keeping the BugBrand dynamic and unpredictable. Like the signals his devices interfere with, at any given point BugBrand can be swayed by its master’s creative whims; it’s from that constant source of fluctuating inspiration that some of the most distinctive audio products in the tumultuous boutique synth market are to be found emanating from a humble workshop on an unassuming street corner in the West of England. It’s hard not to feel that the near-mythical status some of these limited gems engender now will only strengthen with time.

Interview by Oli Warwick

Photography by Lucy Lane