Unpacking Hell – Tension, Boredom, Obsession, and Rene Hell

With Rene Hell’s third LP due for imminent release on PAN, the Los Angeles-based artist speaks to Brendan Arnott about the themes behind it and his latest obsession.

Jeff Witscher’s life is being consumed by chess. Currently averaging about thirty games a day, it’s difficult to tell where the line between hobby and obsession blurs. Games of bullet chess, a sped-up variation of the original game, have even been causing a bit of insomnia in the prolific Los Angeles-based experimental artist current working as Rene Hell. The fact that two tracks on Hell’s new LP explicitly reference the game (most tellingly, a track called “chess sickness”) implies that things might be getting out of control. Trading emails back and forth with each other, I ask him how the game has influenced his music. He’s hesitant to admit a connection, or, a conscious one, at least. “Because I play it so often, it’s constantly on my mind. I wouldn’t say there’s a direct connection between the two, but… it’s definitely doing work on me subconsciously and influencing me to degrees. If I make another record it will have a more prominent presence.”

As most addictions blossom, the game took root in his life slowly, with Witscher beginning as a casual player, only to later start “reading into the basic fundamentals, openings + responses and mating patterns” when he met a friend who shared his passion. The more time he spent with the game, the more it sucked him in and changed his perspective. “It requires so many facets of the mind to work in unison and thousands of hours of study to gain a serious understanding. It’s extremely  frustrating because the parameters of the game are so well defined and specific. Because it has existed for so long that the analysis has been exhausted, it really requires some deep understanding of what’s at stake in complex positions. And so it follows that what is required is understanding, which is quite the opposite of knowledge.” If reading that last sentence seems paradoxically complex, you’re not alone – Witscher is quick to qualify his sentiment, adding, “It’s madness really.”

frustrating because the parameters of the game are so well defined and specific. Because it has existed for so long that the analysis has been exhausted, it really requires some deep understanding of what’s at stake in complex positions. And so it follows that what is required is understanding, which is quite the opposite of knowledge.” If reading that last sentence seems paradoxically complex, you’re not alone – Witscher is quick to qualify his sentiment, adding, “It’s madness really.”

Listen to Witscher’s discography, and you’ll believe that he’s well acquainted with madness – or, at least dissociative identity disorder, given his prolific release schedule under a number of pseudonyms. Rene Hell is his most recent nom de plume, but he runs through other names when it’s convenient. One record might find him operating under his Marble Sky alias, while another limited run of CD-r discs has him going by the name Impregnable, or under the troublingly titled Secret Abuse moniker. But despite the daily rigorous chess rounds and concurrent identities, Witscher’s life is finally taking on a semblance of stability. He’s grounded himself in Los Angeles, making an effort to stay put for a while, despite a preference for being on the road. Vanilla Call Option, his third LP and debut on Bill Kouligas’ Berlin-based PAN label, was largely about travel, and Hell admits to “writing a lot of the patches and working on the compositions while on the go”, editing and redesigning pieces to fit his whims. When Hell tells me, “the advantage of the microprocessor is that you can work anywhere: in airplane, library, the car, etc,” it’s unclear if he’s being patronizing, old fashioned (who calls them microprocessors anymore?) or completely honest.

But Vanilla Call Option is far from an idyllic road trip album to bump with the windows down and the wind rustling your hair. Instead, Hell’s latest effort captures the emotional exhaustion of a life spent perched in the backseat of a van loaded with bags, or sitting in the departures terminal as hordes of screaming, jam-stained children sprint by. The rupturing buzz saw hum on album opener “smile models” sounds like a ripping migraine tunnelling into your brain, and the pinprick arpeggio solo later on in the track has the shape and texture of waking up in a dark, humid hotel room with some half-remembered dream still throbbing its way through your temples.

It’s also a huge departure in style from the reinterpreted classical sounds of Hell’s last LP, The Terminal Symphony, or the uplifting orchestral sounds of “Qi” from his recent split LP with Oneohtrix Point Never. Here, Hell’s compositions are much more impenetrable, shrouded in a layer of subterfuge – the ominous buzz of power tools always lingering in the air. It’s the sound of confusion, or a series of sudden, startling realizations boring into your skull, applying pressure to the soft, meaty pulp of your hypothalamus. It’s next to impossible to glean any meaning from it if you throw it on shuffle while sauntering out for a morning coffee. But if you sit with it and give it time, a whole world of meaning opens up. Much like chess, there are no stakes except what you care to invest of yourself into it.

Describing Vanilla Call Option is a tough task, so I ask Hell for some insight on how it was composed. Though “every record definitely marks new territory, sonically”, he approaches all productions with a similar structure, “the same process of developing sounds first, then arranging a piece with said palette.” While the process stays consistent, Hell admits that his tastes and sense of composition is always shifting and mutating – “it’s like discovered learning, like in chess” he tells me, far from the last reference to the game that will emerge in our conversation. “With this record I was exploring ideas for developing sounds and systems that were interesting to me, ideas in synthesis and automation, which is an obvious benefit of using the computer… then, giving them a narrative. Trying to mesh abstract sound pieces with having a recognizable narrative so that it’s not completely just the sound of an environment”. However, Hell does admit, “inevitably some tracks did end up just being the sound of an environment, which in this case is a computer.”

Though Hell’s never been a stickler for embracing melodic structure (the fact that he smashed a violin for The Terminal Symphony cover art, stating that “it looked a lot nicer” afterwards might give some insight as to his sensibilities), the textures on Vanilla Call Option reject a melodic template entirely – it’s near impossible to find a rhythm or cadence in the rolling waves of noise. Yet Hell claims “I don’t think I made such a strong effort to avoid melody… it just wasn’t readily available to me, it wasn’t practical.” Describing his composition process further, it seems the ideas that took shape didn’t require melody. “The computer as an instrument requires you to build from scratch”, he notes – “so, say you begin with a frequency which sounds like a tone. From there you’re giving it detailed instructions on what to do… melody doesn’t quite figure into the equation until further down the line. I guess because of it not being near the foundation, I didn’t use it.”

While there’s nothing on Vanilla Call Option that sounds unfinished, Witscher’s words on keeping “near the foundation” remind me of a quote from another interview, in which he mentions that his background is rooted in “impatience and instability”. Nothing’s changed since then, he admits. “It’s still quite true… it makes some things I’m interested in very difficult.” Almost instinctively, Hell steers the topic back to chess, the way a fundamentalist might continually bring up religion. “That’s one reason I struggle with chess, because it goes against my nature so vividly. It’s a game that requires many elements for success: natural mental ability, knowledge of fundamentals, creative strategy and practice. But a very important component is mental focus. This is crucial, actually. You have your ability and creative ideas, and your studying of lines and fundamentals, but when you sit down to play, what determines how you will apply these tactically is your mental state. I’m trying to think of an accurate metaphor for this. This applies to other activities as well, like writing music.”

“With this record I was exploring ideas for developing sounds and systems that were interesting to me, ideas in synthesis and automation.”

Intuition seems important to Witscher, both in chess and music. Interestingly, bullet chess often gets slammed by professional players for not relying enough on cold, hard logic – chess world champion Nigel Short once declared that the game “rots the brain just as surely as alcohol.” But intuition, improvisation, and trusting gut feelings seem to be part of the landmark as to what exactly makes experimental or drone music so strangely affective. After all, filmmaker David Lynch supposedly found the highway to his subconscious through the process of transcendental meditation, and while there’s a chance that the whole school of meditation is a big existential ponzi scheme (enlightenment does not come cheap, it seems), I’m curious if tapping into Witscher’s unconscious takes an exerted amount of effort, or whether for an artist with such an extensive catalogue, accessing his subconscious is old hat by now. He darts around my query, admitting “that’s a very complex question” and leaves it at that. Perhaps it’s improvisation, not intuition, that factor into Hell’s work on this latest release then? But Witscher admits that improvising is “something I rarely ever do, or at least, don’t enjoy. Because I don’t possess any skill for instrument which could be developed into technique, I don’t improvise. Improvisation is only interesting when showcasing technique.”

Whatever provides the impulse, there’s something mystical at work in the soggy volley of static that is “unpack; glue”, which oscillates between sounding like a rainstorm and a garbage disposal. It makes the listener question what’s organic, what’s manufactured, where one ends and the other begins. And the closest thing that Vanilla Call Option has that resembles dance music is the sighing “var_len”, which sounds like the last tired exhalation made from a vocal house tune in its death throes. Hell’s  interest is not with the club world, claiming that though he definitely listens to techno, he “clearly understand its function, but it’s not that interesting to me.” In a twist befitting of an experimental musician, he admits that he listens to “quite a bit of mainstream, contemporary country music.” Hell’s soundscapes are much more subtle than any Willie Nelson tracks I’ve heard though, and perhaps some of Witscher’s hesitation to reveal too much about his process comes from the fact that there’s rarely a moment of sweeping grandeur to Vanilla Call Option – even though he has run labels with apocalyptically informed names such as Callow God and Agent of Chaos, there’s nothing on his latest album that makes one think of grandiose evocations of destruction.

interest is not with the club world, claiming that though he definitely listens to techno, he “clearly understand its function, but it’s not that interesting to me.” In a twist befitting of an experimental musician, he admits that he listens to “quite a bit of mainstream, contemporary country music.” Hell’s soundscapes are much more subtle than any Willie Nelson tracks I’ve heard though, and perhaps some of Witscher’s hesitation to reveal too much about his process comes from the fact that there’s rarely a moment of sweeping grandeur to Vanilla Call Option – even though he has run labels with apocalyptically informed names such as Callow God and Agent of Chaos, there’s nothing on his latest album that makes one think of grandiose evocations of destruction.

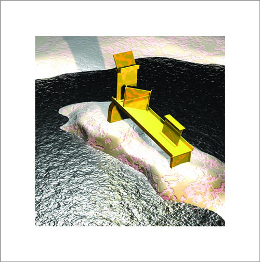

However, it’s not hard to believe that violence still filters into his work somehow. In our conversation, Witscher notes that he just finished a novel he loved, French poet and novelist Jean-Claude Izzo’s Total Chaos. It’s a novel rampant with descriptions of murder and stark, brutal violence, but it feels relevant to Hell’s geographical exploits as well – Izzo’s portrait of Marseilles is so detailed and loving that it seems to come from lived experience – Hell admits that he “enjoyed it so thoroughly because of his descriptions of Marseille and the intimacy he has with that city.” That juxtaposition of violence and beauty is also omnipresent throughout the anxiety-laced Vanilla Call Option, and even the piercing gaze of androgynous model on the cover of the LP emits a sleek dangerousness, reminiscent of an assassin from a Takashi Miike film.

The album’s final piece, “kalishnikov uzi”, alludes to the threat of danger dancing around the barren landscapes Hell crafts, and also possesses a flickering moment of humanity eluding the rest of the album, as one of the few tracks where organic sound filters back in. There’s a moment within it when everything cuts out except for some soft, foreboding piano keys – it’s a rare moment of beauty and humanity in the midst of an otherwise arbitrary and uncaring universe. Witscher admits “that’s the culmination for the LP, and I recorded it last. There are quite a few acoustic recordings that were redesigned in the computer for that piece. I think it’s my favourite track on the record.” The weapon’s inventor, Mikhail Kalashnikov, changed his mind about the most commonly used gun in the planet on his deathbed, stating that he would’ve preferred to have made something useful, like a lawnmower. “Unfortunately, it wasn’t his fate to make a lawnmower.” Witscher counters. What can we expect of Rene Hell’s fate? His answer is unsurprising – “I’ll continue on with chess.”

Interview by Brendan Arnott

Vanilla Call Option is out on PAN next month