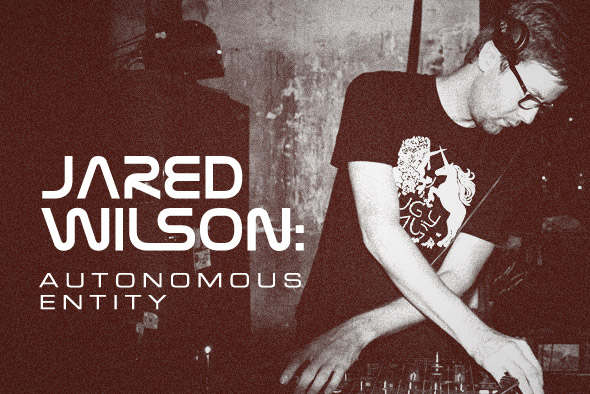

Jared Wilson: Autonomous Entity

Oli Warwick speaks with 7777 Records boss Jared Wilson, a producer whose style and approach marks him out as quite distinct from his Detroit peers.

“I know people have this idea, like this is what Detroit sounds like,” states Jared Wilson as we grab some interview time on his lunch break. “I don’t mind it at all that people would associate me with it, but I don’t think that it really defines what I do.” The notion of Detroit within electronic music is convoluted, defined originally by the work of the Belleville Three and subsequently expanded upon by the various waves of techno and house producers, from Jeff Mills and Carl Craig through to Moodymann, Omar-S and so forth. As such, there are many different shades of dance music that one might readily describe as ‘Detroit’, but Jared Wilson, Michigan-born and bred, sits independent from such links. His sound is fuelled by the legacy started in his hometown in the ’80s, but it reaches to European influences as much as those closer to home.

Tellingly, Wilson forged connections with like-minded labels across the Atlantic including Sweden’s Skudge, France’s DDD, the Netherlands’ Dolly and Scotland’s Dixon Avenue Basement Jams. Meanwhile his intermittent 7777 imprint has, up to this point, acted as a vessel for his own productions bar the recent appearance from long-time friend Todd Osborn with the 303/909 12”. With the inter-connected way in which many of the prominent Detroit producers of the day operate, Wilson is stoutly making his own way through the techno wilderness.

His musical background is quite the textbook story for any Motor City dweller, reaching back to a healthy diet of Motown (alongside his Dad’s country and western endeavours) as a child, to his teenage years spent playing saxophone and embracing the original American resistance music. “I think jazz is just a natural precursor to any music that’s made now,” Wilson opines on one of his first loves. “I don’t think there could be techno without it, just the same as it influences any other type of music.”

His musical background is quite the textbook story for any Motor City dweller, reaching back to a healthy diet of Motown (alongside his Dad’s country and western endeavours) as a child, to his teenage years spent playing saxophone and embracing the original American resistance music. “I think jazz is just a natural precursor to any music that’s made now,” Wilson opines on one of his first loves. “I don’t think there could be techno without it, just the same as it influences any other type of music.”

True enough, amongst the musically-trained within house and techno there is a common correlation between early forays into jazz and eventually being seduced by the call of the machines. Cementing that most Detroit of rites of passage, Wilson’s own introduction to electronic music came through Jeff Mills’ legendary early radio turns on WJLB in the ’80s as The Wizard. “I was super little, between 8 and 12 years old,” Wilson recalls, “and all I would do on the weekends is listen to the Wizard and try to break-dance, and it wasn’t even until later on that I realised who it was and what he was doing.”

Mills’ fearless mixing up of proto-house, synth pop, electro and hip hop (amongst many other things) has long been cited as a great influence for many artists, carrying on the groundbreaking work of The Electrifying Mojo and inspiring a culture of eclecticism in the future DJs of Detroit – something which defined the early ’90s raves that Wilson wound up cutting his teeth on. As a self-proclaimed musical fidget himself when he’s on the decks (“I get bored if a DJ just plays the same type of techno through the whole set,” he states), DJing is the area where Wilson is more in keeping with the Detroit tradition of free-spirited selecting and constantly moving sets. It’s an ethic that reflects the appeal warehouse parties held for him when he first ventured out to them in his mid-teens.

“I don’t think there could be techno without jazz, just the same as it influences any other type of music.”

The nascent rave scene removed the pedestal upon which the performer was traditionally placed (before the DJ got put back up on a stage in due course), instead providing a dark environment filled with sound from anonymous selectors, the shock of the new bringing a startling cross-section of people together. “Before it became stylised, people were coming from all different types of backgrounds,” Wilson explains. “You’d see country and western guys who just wanted to dance. Now when people go to a party I think they have an image of what it should be, whereas back then there wasn’t anything to compare it to.”

After those inspiring experiences, it took until the late ’90s for Wilson to become proactive in electronic music, starting the Feed The Machine imprint and Obsolete production partnership with Adam Shirley, dealing in a plethora of styles from breakcore and drum & bass through to hard-edged techno and electro. While his output in his own name toned down the extreme nature of that material, the fundamental feature of Wilson’s releases since 2007’s Jared Wilson’s Drug Related Stories 12” has been acid – heavy lashings of snarling 303 and rasping drum machines as enamoured with the European interpretation of rave music as anything on home soil.

“We Who Are”, from the aforementioned Drug Related Stories 12”, goes as far as to slip some cheeky samples of “Voodoo Ray” into the intro, and with the disorientating speech from Front 242’s “Funkahdafi” running throughout it’s hard to deny the correlation between Wilson’s music and Europe. The UK took more readily to the likes of Phuture’s “Acid Trax” when the sound first emerged, and Wilson runs with the creative license to tweak the filter and resonance on his lysergic basslines with wild abandon.

Some three years on, The Rise And Fall Of The Machines on Lux highlighted a less aggressive but still decidedly Euro-centric turn for Wilson that brought a greater focus on other synths besides the trusty 303. “They [Lux] picked the tracks that in my opinion were more like [seminal Warp series] Artificial Intelligence or Italo,” he muses on the style that shines through on the release in question, “and it’s funny because the ones that they picked for that were all made in the same week. I borrowed a [Roland] MKS80 and made all those tracks with it as fast as I could while I had it.”

While the Lux release fell neatly into place, Wilson’s experience in sending tracks at the behest of labels has been a chequered one that now feeds into his desire to solely release his music himself on 7777. Citing a concern for over-saturation of his music and a lack of control over the end result, impending appearances on Dixon Avenue and DDD may well be the last you see of Wilson on labels other than his own for some time.

“I feel like the last few things that I’ve done for people I’ve had to rush it,” he explains. “The deadlines are crazy now. It was good when nobody wanted anything ‘cause I could take my time. Some of the time I maybe don’t like the way they were mastered too.”

This new resolve to reclaim control over his output comes at a time when Wilson is also planning to make the leap from his construction day job and devote himself fully to his creative pursuits. It’s a bold move to contemplate at the same time as forgoing the support of other labels, but the upwards trend in exposure, gigs and releases both lights the touch paper and makes the work-music balance even trickier to maintain.

“I’m really in the process of trying to make music full-time because I don’t even have time right now to work on music as much as I’d like to and it’s becoming a hindrance,” Wilson states. “The only thing that stinks is that I would have to spend all the time over in Europe to make it financially work, ‘cause there’s just not the crowds here for that type of music. All the jazz guys did the same thing. They all left the US and went to Europe for ten, twelve years.”

As is evident from his singular path through techno to date, autonomy suits Wilson just fine. He has his peers no doubt, from long-time friend and sometime collaborator Todd Osborn through to opportune European connections that would lead him down a similar path to his jazz forefathers. While it’s apparent that he has no desire to leave Detroit, he proudly displays all the traits of one who follows nothing but his own instincts. With more time to devote to music and no other labels to meet the demands of, the prospect of Jared Wilson’s future in techno is thrillingly unpredictable.

Interview by Oli Warwick