Keeping the wheels in motion: An interview with The Cyclist

Oli Warwick speaks to Andrew Morrison, the Irish producer better known as The Cyclist, responsible for one of this year’s most captivating debut albums in Bones In Motion.

Oli Warwick speaks to Andrew Morrison, the Irish producer better known as The Cyclist, responsible for one of this year’s most captivating debut albums in Bones In Motion.

What is it that makes detuning melodies so appealing? For all the centuries of accomplishment in harmony and refinement in music, there is an allure borne onto the sound of a note shifting pitch that cannot be quantified by the academic approach to sonics. After all, there’s a reason that so many synths come equipped with a pitch wheel to side step the clunky transition from one semitone to another when an artist needs to attain that woozy, disorientating magic that happens between two keys.

However, simply playing out that shift comes on a little stiff compared to the added mystique that can only come from the organic degradation afforded by good old-fashioned tape. Perhaps it’s a generational affection, as carried by the children of the 1980s for whom battle-weary cassettes and tenth-generation long-play VHS were a natural fact of life before the digital age. Either way, there’s no denying that electronica has embraced the charm of the spool-begat warble as a stylistic device with which to enhance the otherworldly qualities of machine music. You could most memorably hear it in the older Boards Of Canada material, or more recently in the lo-fi crust of West Coast stables such as Not Not Fun and Leaving Records.

It is through the latter that a new talent in the field of audio degradation has emerged, peddling his own particular appropriation of distortion to creative ends and making quite an impression on listeners and critics alike as he goes. Andrew Morrison was little known before his Bones In Motion LP surfaced on Matthewdavid’s label in March, having previously released one cassette album, Bending Brass, on Crash Symbols back in 2011. However, an instant appeal shone from the very opening strains of this latest release, piquing interest with a unique vitality uncommon in an over-saturated electronica scene.

“Maybe if you’re a perfect songwriter then you can just go ahead and do the norm,” Andrew states from his university room in Liverpool, “but otherwise I think you really have to think hard about doing something new, especially in electronic music.”

That this is something of a mantra for the way Andrew works is no surprise when you listen to his music. There is a great emphasis on tape distortion, which the lead-in to this piece clearly labours on, but of course stylistic traits can only go so far in music, and Andrew would not be the first to purposefully make his music sound dated. As he candidly puts it himself, “there have been so many things that have been done in various forms, and the idea of experimental was always meant to be that you’re doing something new. A lot of things people are doing are interesting experiments, but actually they’re just repeating what someone else has done, without putting any real heart into it.”

Indeed, on that first listen to Bones In Motion there is an overwhelming sense of surprise, of the unexpected, as ideas bloom and flourish exponentially throughout each track, rarely stopping in one place for long before charging on to the next dramatic event. There is certainly an experimental spirit to his music, but it’s offset by an immediacy that wastes no time in hooking you in to a soundworld of audible detritus and plush melodic vistas. Part of that engaging quality comes no doubt from the ever-shifting landscape that unfolds before your ears, and it’s a concern that sits at the forefront of Andrew’s intentions when he’s at work.

“I do just get to this point when, after 30 seconds I want to make some massive shift again and get it to a whole different headspace,” Andrew admits. “It can’t stay anything like it was before.”

It’s an approach Andrew succeeds at, and it doesn’t stop at the contents of the tracks themselves. With his discography to date consisting solely of two albums, it seems as though the long player is his preferred format, which naturally leads to the suggestion that he prefers complete bodies of work that tie together cohesively and tell a story (let’s not go as far as using the word ‘concept’ though). Where Andrew’s quest for the new is concerned though, consistency across a release is low on the agenda.

“When I actually make tracks I’m trying to make them sound very different from each other,” he reveals, “almost as if they’re half coming from someone else, like a compilation of sounds rather than an album. Even the recording and the mastering I changed every time. Maybe a couple of the tracks remain in the same mindset, but for most of them I’m thinking totally different things each time.”

One curious sideline from this refusal to work all the tracks on Bones In Motion towards a shared goal is the way the final running order was formed. A far cry from the intensive drafting and re-drafting of possible tracklists that perfectly plot the trajectory of the listening experience, the sequence you listen to is almost exactly chronological to the order in which Andrew made the album. It’s hard to know how common an occurrence that might be, but it adds a certain real-world narrative where Andrew had not consciously composed one himself.

Of course, for all the individuality that shines through, there are also plenty of reference points to draw on within Andrew’s music, and it’s clear that a 4/4 heart lies beating at the core of many of the tracks. This is not something explicitly aped in a quest for an impact on the dancefloor, but rather used as an undercarriage of rhythm upon which the swathes of esoteric noise and melody can reside.

“My main house and techno inspirations were from the 80s early experiments of some house musicians,” Andrew explains, “but I tried to steer clear of any of those straight-down genre sounds like stabbing minor chords because I wanted this to be my own. You can see the influences without saying this is that genre. I could make some kind of housey screaming messed up things,” he continues, “and I have done, but I didn’t decide to release them because I felt that’s the sound of knocked off Cabaret Voltaire or something.”

It’s perhaps not surprising that Andrew mentions Cabaret Voltaire as a reference point of his own. After all, his approach displays an obvious fondness for the methods of the past, and as it turns out his roots in electronic music lie in chance discoveries of post-punk and industrial oddities as a youngster growing up in Derry. Northern Ireland may not be a hotbed for cutting edge musical happenings a lot of the time, as Andrew is quick to point out, but in his own homestead there was fortunately a treasure trove of wax for his older brother to dig through, which would lead on to shape his own tastes immeasurably.

“My dad’s old record collection would have some old post-punk, early 80s kind of things,” Andrew reveals. “Early Human League, that kinda stuff. It was mostly punk that he had, but my brother would always find something in that collection. He might not even listen to it again, but I would just go crazy for it, and would have to find every recording I could of some of the bands, like Suicide or whatever.” If you listen to a track like “Reels”, the sprawling eight minute epic of skuzzy guitars and full-throttle momentum that comes near the end of Bones In Motion, it’s easier to think of Can than it is Cybotron, and the addition of punk (along with krautrock, new wave etc.) into Andrew’s musical vocabulary makes perfect sense. It’s indicative that the posters that adorn the wall of his room include The Stone Roses and Iggy Pop’s The Idiot.

“You really have to think hard about doing something new, especially in electronic music.”

As well as those pointers into the world of scratchy, experimental bands of the era, Andrew’s other major cue in starting his path into production came once again from his brother and the purchase of a laptop and a four-track cassette recorder. It didn’t take long to start testing out ways of making noise with this rudimentary set up, and it has set the tone for Andrew’s style ever since. “I did more things with the four track than I did with the laptop,” he recalls, “and started making cassette tape loops and found that more interesting than a grid computer screen. Of course I did realise after a couple of years that you can do so much with computers that you can’t really do with other things…”

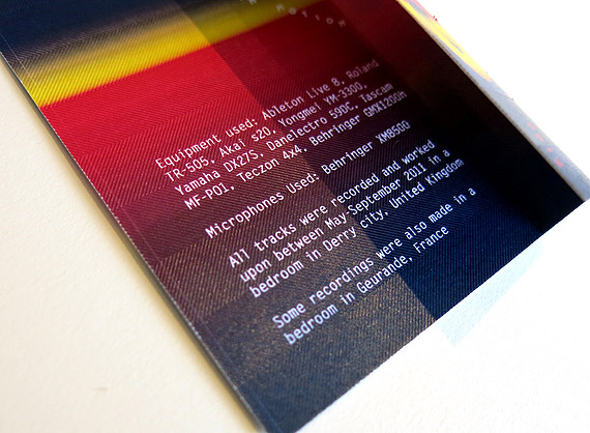

Andrew’s voice trails off, the lack of excitement in digital production palpable compared to the way he lights up when talking about the joys of tape mangling. At this point he shows off the set up he currently operates, and it seems as though not too much has changed. Two four-track tape machines, a budget Yamaha FM synth and an old Akai sampler form the crux of the operation, with a laptop to bring everything together and a smattering of effects pedals wired into the mix in various places.

“It’s generally a very cheap set up,” Andrew explains, “mainly because I haven’t had the money to buy more expensive things, but I kinda like trying to get something interesting with crap.” It’s safe to say that The Cyclist wouldn’t sound the same were he operating in a professional recording studio. “There have always been instances of bands using whatever crap electronic things they could find to come up with good sounds,” he adds, “but people are usually striving for the best they can get rather than just trying to be creative with what they can find.”

There are two schools of thought when it comes to perceived ‘difference’ in music. Some artists are quite set against notions of striving to purposefully make their music unusual, arguing that it becomes a pretention at odds with the creative process. As we’ve already heard, that’s not the view that Andrew takes, and while his budget set up was borne out of necessity in the beginning, his own satisfaction and pleasure in making music now comes from a time-honoured relationship with the tape format that borders on the ritualistic.

“I’m very aware of the amount and degree at which I distort these things,” Andrew says with a glint of pride in his eyes. “I want to detune them, I want to warble them. I sometimes liked records more because they’d been distorted through a bad record or from a crappy old tape. Without some of the distortion of certain sounds on my album, they might not be interesting at all. In the same way if you distort a guitar it becomes something more powerful, or for example The Sonics. They distorted their entire sound to make it more crazy and energetic, and I guess that’s what I’m trying to do.”

While it might be a mastering engineer’s worst nightmare, it’s hard to argue with the impact of a band like The Sonics, who sounded positively gargantuan even by today’s standards through their over-cooked sound, even if they were recording via primitive means back in the 60s. The same practice is carried through to today, with a notable advocate of artistic overdrive being Flying Lotus and Daddy Kev’s Echo Chamber studio through which all the Brainfeeder material passes. After all, sometimes perfection just isn’t as exciting.

“Whenever I listened to house and techno everything seemed to be pretty damn pristine quality,” Andrew considers. “Minimal techno was a pretty big thing when I started listening and you couldn’t really have a distorted sound, or you couldn’t have any noise in the background because that would just be a failure of a track.”

Andrew’s employment of tapes to facilitate his sound takes on many guises. In one instance he might be running his synth through the four-tracks a few times to wear it down, in the next reaching for samples from his personal archive of recorded sonic doodles. “I wouldn’t call them releasable,” Andrew says of his backlog of audio bits and pieces. “They’re just sound experiments that I can then use to resample. Some of those tapes I used were already pretty crusty by the time I came round to them, and I don’t really take care of them so when I come back to them they sound a bit different.”

Again there is a sense that in his relationship with the medium, Andrew is applying some kind of slow-release meditation on his sonic identity through deliberately mis-treating his cassettes. He talks of leaving them next to radiators or in the sun to facilitate the debilitation of Ferox, sounding akin to a mischievous child intent on tying his favourite action figures to fireworks and watching them shoot up to explode in the sky.

It’s not all just tapes and time that goes into the production process for him though. If there were one noticeable advancement that shines through on Bones In Motion when comparing it to Bending Brass, it would be in the drums. Opening track “Feel Beauty” especially gives this impression, starting on a muffled kick thrum but gradually opening up into a tumultuous break that flails with kinetic energy, sounding to all intents and purposes like a live kit. “I did record more of the drums,” Andrew confirms when pressed on whether he was using breaks and samples at all. “You maybe wouldn’t call them drums though because they’re just percussion noises. I don’t actually have a drum kit, but there are more sounds that are actually recorded in a room with a microphone, whereas before I just used straight sequencing.”

Sourced from tinkering around the home in Derry, it’s hard to depict where some of the noises may have been derived from when you listen to the album, no doubt as a result of some heavy-handed processing on the raw recording. He is happy to point out that nearly all the drums on “Visions” came from these microphone missions, which isn’t so surprising when you hear the ramshackle kitchen-sink textures of the wonky house groove within. “For Bones In Motion I felt better at patterning and I learnt more to do with rhythmics,” Andrew adds, acknowledging the fact that his arrangements flex and flutter with a greater dexterity than before. “I was distorting samples, and using as many varied sounds as possible, like one single drum could not be used for more than one track. Every drum had to be completely warbled in its own way.”

Ever the committed artist though, Andrew isn’t content to rest on his laurels, already building on his techniques for future projects. “Even the next things I’m working on, I want to evolve it a lot more. I don’t know how more complex you can make something but I’ll try!” On the immediate horizon is a somewhat surprising release for Apnea, the Spanish label more commonly associated with minimal techno acts such as Alex Under, Damian Schwartz and Tadeo. Having lain dormant for some time, it would seem that a new order of business lies in store for the label with Andrew signed up for a single. “Of course I’m just making something of my own,” he is quick to state, “but whether they’ll come out happy with it in the end or not I don’t know!”

Beyond that Andrew is focused on making his next album, and also honing his burgeoning live set. Having done a small Leaving Records tour with Matthewdavid and company he has a show together, although the limitations of his home studio have revealed themselves. “I wish I could do something with more of my equipment for a live set,” Andrew explains, “but everything’s untrustworthy! This current laptop I have I’ve had for about five years, and it’s falling apart, I can stick my fingers through different bits of it! Watch this…”

In this instance, as he taps his laptop screen to demonstrate the sizable wobble it boasts, it becomes strangely worrying to imagine Andrew’s success building and leading to better equipment, more stable recording facilities and higher fidelity. There’s little doubt that he has the gift to realise some exciting ideas whatever his means, helped of course by his sheepishly admitted musical training and a clear vision of what he wants to achieve, but of course a lot can happen to artists as they grow into their careers, and it’s still early days for The Cyclist. Truthfully though, it’s hard to imagine he could leave the warm and fuzzy embrace of a knackered cassette for all the production values in the world.

Interview by Oli Warwick

The Cyclist shot by Shaun Bloodworth